Black people

Black is a racial, political, sociological or cultural classification of people. No people are literally colored black, but many people who have dark skin color are considered to be.

Some assert that only people of relatively recent African descent are black, while others argue that black may refer to individuals with dark skin color regardless of ethnic origin.[1][2]

Single origin hypothesis

The low level of genetic variation across populations surprised many in the scientific community. Scientists believe the reason for this low level of variation is because the entire world population of 6.5 billion is descended from a small group of people, probably numbering no more than 2,000, who lived in Africa 70,000 years ago.[3][4] From this small group, an even smaller group left Africa by crossing the Red Sea and proceeded to populate the rest of the world. The differences in physical appearance between the various peoples of the world is as a result of adaptations to the different environments that the early pioneers who left Africa made in order to conquer the new lands to which they traveled.

The African population retains the great degree of physical variation. Even though all Africans share a skin color that is dark relative to other peoples of the world, they actually differ significantly in physical appearance. Examples include the Dinka, some of the tallest people in the world and the Mbuti, the shortest people in the world. Others such as the Khoisan people have an epicanthal fold similar to the peoples of Central Asia. A recent study found that Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest skin color diversity within population.[5]

Dark skin

Scientists now believe that humans first appeared in Africa between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago[6] . Dark skin helped protect against skin cancer that develops as a result of ultraviolet light radiation, causing mutations in the skin. Furthermore, dark skin prevents an essential B vitamin, folate, from being destroyed. Therefore, in the absence of modern medicine and diet, a person with dark skin in the tropics would live longer, be more healthy and more likely to reproduce than a person with light skin. Scientists point to the fact that white Australians have some of the highest rates of skin cancer as evidence of this expectation.[7] Conversely, as dark skin prevents sunlight from penetrating the skin it hinders the production of vitamin D3. Hence when humans migrated to less sun-intensive regions in the north, low vitamin D3 levels became a problem and lighter skin colors started appearing. The people of Europe, who have low levels of melanin, naturally have an almost colorless skin pigmentation, especially when untanned. This low level of pigmentation allows the blood vessels to become visible and gives the characteristic pale pink color of white people. The difference in skin color between black and whites is however a minor genetic difference accounting for just one letter in 3.1 billion letters of DNA.[8]

Africans in the Americas

Approximately 12 million Africans were forcibly shipped to the Americas during the Atlantic slave trade from 1492 to 1888. Today their descendants number approximately 150 million.[9] Many have a multiracial background of African, Amerindian, European and Asian ancestry. The various regions developed complex social conventions with which their multi-ethnic populations were classified.

United States

In the first 200 years that blacks had been in the US they commonly referred to themselves as Africans. In Africa, people primarily identified themselves by tribe or ethnic group and not by skin color. Individuals would be Asante, Yoruba, Kikongo or Wolof. But when Africans were brought to the Americas they were forced to give up their tribal affiliations for fear of uprisings. The result was the Africans had to intermingle with other Africans from different tribal groups. This is significant as Africans came from a vast geographic region, a coastline stretching from Senegal to Angola and in some cases from the south east coast such as from Mozambique. A new identity and culture was born that incorporated elements of the various tribal groups and also European elements such as Christianity and English. This new identity was now based on skin color and African ancestry rather than any one tribal group.[10]

When the trans-atlantic slave trade was declared illegal in 1807 the vast majority of blacks were US born, hence use of the term African became problematic. Though initially a source of pride, many blacks feared its continued use would be a hindrance to their fight for full citizenship in the US. They also felt that it would give ammunition to those who were advocating repatriating blacks back to Africa. In 1835 Black leaders called upon Black Americans to remove the title of African from their institutions and replace it with Negro or Colored American. A few institutions however elected to keep their historical names such as African Methodist Episcopal Church. Negro and colored remained the popular terms until the late 1960s[11].

The term "black" was used throughout but not frequently as it carried a certain stigma. In the 1963, I Have a Dream speech,[12] Dr. Martin Luther King uses the term Negro 15 times and black 4 times. Each time he uses black it is in parallel construction with white (e.g., black men and white men).[13] With the successes of the civil rights movement a new term was needed to break from the past and help shed the reminders of legalized discrimination. In place of Negro, black was promoted as standing for racial pride, militancy and power. Some of the turning points included Kwame Toure's (Stokely Carmichael) use of the term Black Power and the release of James Brown's song "Say It Loud - I'm Black and I'm Proud".

In 1988 Jesse Jackson urged Americans to use the term African American because the term has a historical cultural base. Since then African American and black have essentially a coequal status. There is still much controversy over which term is more appropriate. Some strongly reject the term African American in preference for black citing that they have little connection with Africa. Others believe the term black is inaccurate because African Americans have a variety of skin tones.[14] Surveys show that when interacting with each other African Americans prefer the term black, as it is associated with intimacy and familiarity. The term "African American" is preferred for public and formal use.[15]

One drop rule

According to the United States' colloquial term one drop rule, a black is any person with any known African ancestry.[16] The one drop rule is virtually unique to the United States and was applied almost exclusively to blacks. Outside of the US, definitions of who is black vary from country to country but generally, multiracial people are not required by society to identify themselves as black. The most significant consequence of the one drop rule was that many African Americans who had significant European ancestry, whose appearance was very European, would identify themselves as black.

The one drop rule originated as a racist attempt to keep the white race pure, however one of its unintended consequences was uniting the African American community and preserving an African identity. Some of the most prominent civil rights activists were multiracial but yet stood up for equality for all. It is said that W.E.B. Du Bois could have easily passed for white yet he became the preeminent scholar in Afro-American studies.[17] He chose to spend his final years in Africa and immigrated to Ghana where he died aged 95. Other scholars such as Booker T. Washington and Frederick Douglass both had white fathers.[18] Even the more radical activists such as Malcolm X and Louis Farrakhan both had white grandparents. That said, colorism, or intraracial discrimination based on skin tone, does affect the black community. It is a sensitive issue or a taboo subject. Open discussions are often labeled as "airing dirty laundry".[19] [20]

Many people in the United States are increasingly rejecting the one drop rule, and are questioning whether even as much as 50% black ancestry should be considered black. Although politician Barack Obama self-identifies as black, 55 percent of whites and 61 percent of others classified him as biracial instead of black after being told that his mother is white. Blacks were less likely to acknowledge a multiracial category, with 66% labeling Obama as black.[21] However when it came to Tiger Woods, only 42% of African-Americans described him as black, as did only 7% of White Americans.[22]

Race in Brazil

Unlike in the United States race in Brazil is based on skin color and physical appearance rather than ancestry. A Brazilian child was never automatically identified with the racial type of one or both parents, nor were there only two categories to choose from. Between a pure black and a very light mulatto over a dozen racial categories would be recognized in conformity with the combinations of hair color, hair texture, eye color, and skin color. These types grade into each other like the colors of the spectrum, and no one category stands significantly isolated from the rest. That is, race referred to appearance, not heredity.[23]

There is some disagreement among scholars over the effects of social status on racial classifications in Brazil. It is generally believed that upward mobility and education results in reclassification of individuals into lighter skinned categories. The popular claim is that in Brazil poor whites are considered black and wealthy blacks are considered white. Some scholars disagree arguing that whitening of one's social status may be open to people of mixed race, but a typically black person will consistently be identified as black regardless of wealth or social status.[24][24][25]

Statistics

| Demographics of Brazil | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | White | brown | black |

| 1835 | 24.4% | 18.2% | 51.4% |

| 2000 | 53.7% | 38.5% | 6.2% |

From the year 1500 to 1850 an estimated 3.5 million Africans were forcibly shipped to Brazil.[24] An estimated 80 million Brazilians, almost half the population, are at least in part descendants of these Africans. Brazil has the largest population of Afro-descendants outside of Africa. In contrast to the US there were no segregation or anti-miscegenation laws in Brazil. As a result miscegenation has affected a large majority of the Brazilian population. Even much of the white population has either African or Amerindian blood. According to the last census 54% identified themselves as white, 6.2% identified themselves as black and 39.5% identified themselves as Pardo (brown)- a broad multiracial category.[26]

A philosophy of whitening emerged in Brazil in the 19th century. Until recently the government did not keep data on race. However statisticians estimate that in 1835 half the population was black, one fifth was Pardo (brown) and one fourth white. By 2000 the black population had fallen to only 6.2% and the Pardo had increased to 40% and white to 55%. Essentially most of the black population was absorbed into the multiracial category by miscegenation.[23]

Discrimination

Because of the ideology of miscegenation, Brazil has avoided the polarization of Society into black and white. The bitter and sometimes violent racial tensions that divide the US are notably absent in Brazil. However the philosophy of the racial democracy in Brazil has drawn criticism from some quarters. Brazil has one of the largest gaps in income distribution in the world. The richest 10% of the population earn 28 times the average income of the bottom 40%. The richest 10 percent is almost exclusively white. One-third of the population lives under the poverty line of which blacks and other non-whites account for 70 percent of the poor.[27]

In the US blacks earn 75% of what what whites earn, in Brazil non-whites earn less than 50% of what whites earn. Some have posited that Brazil does in fact practice the one drop rule when social economic factors are considered. This because the gap income between blacks and other non-whites is relatively small compared with the large gap between whites and non-whites. Other factors such as illiteracy and education level show the same patterns.[28] Unlike in the US where African Americans were united in the civil rights struggle, in Brazil the philosophy of whitening has helped divide blacks from other non-whites and prevented a more active civil rights movement.

Though Afro-Brazilians make up half the population there are very few black politicians. The city of Bahia for instance is 80% afro-Brazilian but has never had a black mayor. Critics indicate that in US cities like Detroit and New Orleans that have a black majority, have never had white mayors since first electing black mayors in the 1970s.[29]

Non-white people also have limited media visibility. The Latin American media, in particular the Brazilian media, has been accused of hiding its black and indigenous population. For example the telenovelas or soaps are said to be a hotbed of white, largely blonde and blue/green-eyed actors who resemble Scandinavians or Anglos more than they resemble the typical whites of Brazil. [30][31] [32]

These patterns of discrimination against non-whites has lead some to advocate for the use of the Portuguese term 'negro' to encompass non-whites so as to renew a black consciousness and identity, in effect an African descent rule.[33]

The Arab world

According to Dr. Carlos Moore, resident scholar at Brazil's Universidade do Estado da Bahia, Afro-multiracials in the Arab world self-identify in ways that resemble Latin America. Moore recalled that a film about Egyptian President Anwar Sadat had to be canceled when Sadat discovered that an African-American had been cast to play him. (In fact, the 1983 television movie Sadat, starring Louis Gossett, Jr., was not canceled; although the Egyptian government refused to let the drama air in Egypt, partially on the grounds of the casting of Gossett, the objections did not come from Sadat, who had been assassinated two years earlier.) Sadat considered himself white, according to Moore. Moore claimed that black-looking Arabs, much like black looking Latin Americans consider themselves white because they have some distant white ancestry.[34] Similarly, 19th century slave trader Tippu Tip is often identified as Arab[35] despite having an unmixed African mother, in part because of patrilineality.[citation needed]

In general, Arabs had a more positive view of black women than black men, even if the women were of slave origin. More black women were taken across the Sahara to North Africa than men, and some even gave birth to the children of Arab rulers. When an enslaved woman became pregnant with her Arab captor's child, she became “umm walad” or “mother of a child”, a status that granted her privileged rights. The child, however, would have prospered from the wealth of the father and been given rights of inheritance.[10] Because of patrilineality, the children were born free and sometimes even became successors to their ruling fathers, as was the case with Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur, (whose mother was a Fulani concubine), who ruled Morocco from 1578-1608. Such tolerance, however, was not extended to wholly black persons, even when technically "free," and the notion that to be black meant to be a slave became a common belief.[36]

Apartheid era in South Africa

In South Africa during the apartheid era, the population was classified into four groups: Black, White, Asian (mostly Indian), and Coloured. The Coloured group included people of mixed Bantu, Khoisan, and European descent (with some Malay ancestry, especially in the Western Cape). There is still much discomfort in publicly discussing the Coloured identity in South Africa. Even the use of the term coloured is quite sensitive. The Coloureds occupy an intermediary position between blacks and whites in South Africa.

The apartheid bureaucracy devised complex (and often arbitrary) criteria in the Population Registration Act to determine who belonged in which group. Minor officials administered tests to enforce the classifications. When it was unclear from a person's physical appearance whether a person was to be considered colored or black, the pencil test was employed. This involved inserting a pencil in a person's hair to determine if the hair was kinky enough for the pencil to get stuck.[37]

During the apartheid era the coloureds were also oppressed and discriminated against. However they did have limited rights and overall had slightly better socioeconomic conditions than blacks. In the post apartheid era the government's policies of affirmative action have favored blacks over coloureds. Some Black South Africans openly state that coloureds did not suffer as much as they did during apartheid. The popular saying by coloured South Africans to illustrate this dilemma is:

Not white enough under apartheid and not black enough under the ANC

Other than by appearance coloureds can be distinguished from blacks by language. Most speak Afrikaans or English as a first language as opposed to Bantu tribal languages such as Zulu or Xhosa. They also tend to have more European sounding names than Bantu names.[38]

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is the term used to describe African countries located south of the Sahara desert. It is used as a cultural and ecological distinction from North Africa. Because the indigenous people of this region are primarily dark skinned it is sometimes used as a politically correct term or euphemism for Black Africa.[40] Some criticize the use of the term in defining black Africans because the Sahara desert spans across many countries such as Chad, Mali, Sudan, Niger, and Mauritania that belong to both North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Some also argue that it is a racist code word. Owen 'Alik Shahadah argues that the term sub-Saharan Africa is a product of European imperialism:

Sub-Saharan Africa is a racist byword for "primitive", a place which has escaped advancement. Hence, we see statements like “no written languages exist in Sub-Saharan Africa.” “Ancient Egypt was not a Sub-Saharan African civilization.” Sub-Sahara serves as an exclusion, which moves, jumps and slides around to suit negative generalization of Africa.[10]

However some Africans actually prefer to be culturally distinguished from their northern neighbors.[41]

The U.S. census race definitions says a black is a person having origins in any of the black racial groups of Africa. It includes people who indicate their race as "Black, African Am., or Negro," or who provide written entries such as African American, Afro American, Kenyan, Nigerian, or Haitian. However, the Census Bureau notes that these classifications are socio-political constructs and should not be interpreted as scientific or anthropological.[39]

Ancient Egyptians

There is considerable controversy over who the Ancient Egyptians were. Afrocentrists scholars such as Cheikh Anta Diop argue that ancient Egypt was primarily a black civilization. As evidence they cite quotes from Herodotus, who stated around 450 B.C.:

The Colchians, Ethiopians and Egyptians have thick lips, broad nose, woolly hair and they are burnt of skin."[42]

Mainstream scholars tend to avoid the issue of race but contend that Ancient Egypt was a multicultural society of Middle eastern and African Influences[43][44]. They also state that the Egyptians viewed themselves as a distinct people separate from their neighbors.

Ancient Egypt was at the time the most advanced of civilizations. Egyptians in the media were often portrayed as Caucasians[45]. However recent evidence has began to shed light on influence of black Africa in ancient Egypt. Based on archaeological evidence black or Africoid people were present in Ancient Egypt. What remains controversial is when they arrived, their exact roles, significance and influence.[46]

Biblical perspective

According to some historians, the tale in Genesis 9 in which Noah cursed the descendants of his son Ham with servitude was a seminal moment in defining black people, as the story was passed on through generations of Jewish, Christian and Islamic scholars.[47] According to columnist Felicia R. Lee, "Ham came to be widely portrayed as black; blackness, servitude and the idea of racial hierarchy became inextricably linked." Some people believe that the tradition of dividing humankind into three major races is partly rooted in tales of Noah's three sons repopulating the Earth after the Deluge and giving rise to three separate races.[48]

The biblical passage, Book of Genesis 9:20-27, which deals with the sons of Noah however makes no reference to race. The reputed curse of Ham is not on Ham, but on Canaan, one of Ham's sons. This is not a racial but geographic referent. The Canaanites, typically associated with the region of the Levant (Palestine, Lebanon, etc) were later subjugated by the Hebrews when they left bondage in Egypt according to the Biblical narrative.[49][50] The alleged inferiority of Hamitic descendants also in not supported by the Biblical narrative, nor claims of three races in relation to Noah's sons. Shem for example seems a linguistic not racial referent. In short the Bible does not define blacks, nor assign them to racial hierarchies.[50]

Historians believe that by the 19th century, the belief that blacks were descended from Ham was used by southern United States whites to justify slavery.[51] According to Benjamin Braude, a professor of history at Boston College:

in 18th- and 19th century Euro-America, Genesis 9:18-27 became the curse of Ham, a foundation myth for collective degradation, conventionally trotted out as God's reason for condemning generations of dark-skinned peoples from Africa to slavery.[51]

Author David M. Goldenberg contends that the Bible is not a racist document. According to Goldenberg, such racist interpretations came from post-biblical writers of antiquity like Philo and Origen, who equated blackness with darkness of the soul.[52]

Non-African peoples

There are several groups of dark skinned people who live in various parts of Asia, Australia and the South pacific. They include the Indigenous Australians, the Melanesians and various indigenous peoples sometimes collectively known as Negritos. The term "negrito" is sometimes considered pejorative.

By their external physical appearance they resemble Africans with dark skin and sometimes tightly coiled hair. Genetically they are distant from Africans and are more closely related to the surrounding Asian populations.[53]

The Dutch colonial officials considered the Taiwanese aborigines to be "Indians" or "blacks", based on their prior colonial experience in what is currently Indonesia.

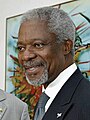

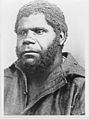

Gallery

The following individuals are black by virtually all definitions cited in this article.

-

San man

The following individuals are considered black by some, multiracial by others:

-

Blasian girl

The following individuals are black to those who define the term by appearance rather than African ancestry

-

Vanuatu woman

-

Ati woman from the Philippines

Footnotes

- ^ Negritos and Australoids have dark skin, but do not have recent African ancestry. Some members of these groups consider themselves, or have been considered, black.

- ^ black. (n.d.). Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Retrieved April 13, 2007, from Dictionary.com website

- ^ Whitehouse, David (9 June, 2003). "When humans faced extinction". BBC.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Brush with extinction". ABC News Online.

- ^ Relethford, J.H. (October 2000). "Human Skin Color Diversity Is Highest in Sub-Saharan African Population". Human Biology. 72: 773–80.

- ^ "Atlas of Human Journey".

- ^ "Australia Struggles with Skin Cancer".

- ^ "Scientists find DNA change accounting for white skin". Washington Post.

- ^ "Community Outreach" Seminar on Planning Process for SANTIAGO +5 , Global Afro-Latino and Caribbean Initiative, February 4, 2006

- ^ a b c Shahadah, Owen 'Alik. "Linguistics for a new African reality".

- ^ African American Journeys to Africa page63-64

- ^ Martin Luther King, Jr. (August 28, 1963). I Have a Dream (Google Video). Washington, D.C.

- ^ Tom W., Smith (Winter, 1992). "Changing Racial Labels: From "Colored" to "Negro" to "Black" to "African American"" (PDF). The Public Opinion Quarterly. 56. Oxford University Press.: 496–514.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ McWhorter, John H. (September 8, 2004). "Why I'm Black, Not African American". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Miller, Pepper (2006). What's Black About? Insights to Increase Your Share of a Changing African-American Market. Paramount Market Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0972529098.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ James, F. Davis. "Who is Black? One Nation's Definition". PBS.

- ^ Nakao, Annie (January 28, 2004). "Play explores corrosive prejudice within black community". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "Mixed Historical Figures".

- ^ Crawford, Larry D. "Racism, Colorism and Power".

- ^ Jones, Trina (October 1972). "Shades of Brown: The Law of Skin Color". Duke Law Journal. 49. Duke University School of Law: 1487.

- ^ "Obama and 'one drop of non-white blood'". BBS News. April 13 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ White, John Kennet. "Barack Obama and the Politics of Race". Catholic University of America.

- ^ a b Skidmore, Thomas E. (April 1992). "Fact and Myth: Discovering a Racial Problem in Brazil" (PDF). Working Paper. 173.

- ^ a b c Edward E., Telles (2004). Race in Another America: The Significance of Skin Color in Brazil. Princeton University Press. pp. 95–98. ISBN 0691118663.

- ^ Telles, Edward E. (3 May 2002). "Racial Ambiguity Among the Brazilian Population" (PDF). Ethnic and Racial Studies. 25. California Center for Population Research: 415–441.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook: Brazil".

- ^ Barrolle, Melvin Kadiri. "African 'Americans' in Brazil". New America Media.

- ^ Roland, Edna Maria Santos. "The Economics of Racism: People of African Descent in Brazil".

- ^ Charles Whitaker, "Blacks in Brazil: The Myth and the Reality," Ebony, February 1991

- ^ Soap operas on Latin TV are lily white

- ^ The Blond, Blue-Eyed Face of Spanish TV

- ^ Skin tone consciousness in Asian and Latin American populations

- ^ Brazil Separates Into a World of Black and White, Los Angeles Times, September 3, 2006

- ^ Musselman, Anson. "The Subtle Racism of Latin America". UCLA International Institute.

- ^ http://www.ntz.info/gen/n00880.html#id04963

- ^ Hunwick, John. "Arab Views of Black Africans and Slavery" (PDF).

- ^ Nullis, Clare (2007). "Township tourism booming in South Africa". The Associated Press.

- ^ du Preez, Max (April 13, 2006). "Coloureds - the most authentic SA citizens". The Star.

- ^ a b http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/meta/long_309540.htm Quickfacts: U.S. Bureau of the Census

- ^ Keita, Lansana (2004). "Race, Identity and Africanity: A Reply to Eboussi Boulaga". CODESRIA Bulletin, Nos. 1 & 2. Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa: 16.

- ^ Keith B., Richburg (Reprint edition (July 1, 1998)). Out of America: A Black Man Confronts Africa. Harvest/HBJ Book. ISBN 0156005832.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Huge Ancient Egyptian Photo Gallery".

- ^ Building bridges to Afrocentrism

- ^ Were the Ancient Egyptians black or white

- ^ "The Identity Of Ancient" (PDF). Note: Large file, slow connection

- ^ Basil Davidson. http://www.lincoln.edu/history/his307/davidson/1/dif3.wmv The Nile].

{{cite AV media}}: External link in|title= - ^ Bernard Lewis, Race and Slavery in the Middle East: An Historical Enquiry, (Oxford University Press, 1982), pp. 28-117

- ^ "The Descendants of Noah".

- ^ Redford, Donald B. (1993). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press. pp. 23–87. ISBN 0691000867.

- ^ a b Goldenberg, David M. (New Ed edition (July 18, 2005)). The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691123705.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Felicia R. Lee, Noah's Curse Is Slavery's Rationale, Racematters.org, November 1, 2003

- ^ Goldenberg, D. M. (2005) The Curse of Ham: Race & Slavery in Early Judaism, Christian, Princeton University Press

- ^ Thangaraj, Kumarasamy (21 January 2003). "Genetic Affinities of the Andaman Islanders, a Vanishing Human Population" (PDF). Current Biology. 13, Number 2: 86-93(8).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)