Ultimate frisbee

Ultimate (commonly called Ultimate Frisbee) is a non-contact competitive team sport played with a 175 gram flying disc. The object of the game is to score points by passing the disc to a player in the opposing end-zone, similar to an end-zone in American football or Rugby. Players may not run while holding the disc. Ultimate is distinguished by its Spirit of the Game—the principles of fair play, sportsmanship, and the joy of play.

While originally called "ultimate Frisbee", "Frisbee" is a trademarked brand name for discs made by Wham-O, and in fact discs made by the Frisbee competitor Discraft are now the most commonly used in the sport because of Wham-O's attempt to gain money off of the sport in the 1970s (see the section in the Wham-O article). The game is played using a 175 g disc; for some national and international tournaments, only discs that have been approved by the governing body responsible for that tournament may be used.

History

The early days (late 1960s)

While the exact origins of ultimate contain some debate and uncertainty, it is generally believed that teenagers from Columbia High School in Maplewood, New Jersey were the first to play the precursor to ultimate initially as an evening pastime. Joel Silver proposed a school Frisbee team on a whim in the fall of 1968. The following spring, a group of students got together to play what Silver claimed to be the "ultimate sports experience," adapting the game from a form of Frisbee football, likely learned from Jared Kass while attending a summer camp at Northfield Mount Hermon, Massachusetts where Kass was teaching. Kass came up with the name "ultimate", when asked by a student, on the whim that it was the ultimate sport. Kass created the game with a group of friends while at Amherst College. The students who played and codified the rules at Columbia High School were an eclectic group of students including leaders in academics, student politics, the student newspaper, and school dramatic productions. The sport became identified as a counter culture activity. The first definitive history of the sport was published in December 2005, "ULTIMATE--The First Four Decades." [1] While the rules governing movement and scoring of the disc have not changed, the early Columbia High games had sidelines that were defined by the parking lot of the school and team sizes based on the number of players that showed up. Gentlemanly behavior and gracefulness were held high. (A foul was defined as contact "sufficient to arouse the ire of the player fouled.") No referees were present, which remarkably still holds true today as all ultimate matches (even at high level events) are self-officiated. At higher levels of play 'observers' are often present. Observers only make calls when appealed to by one of the teams, at which point the result is binding. [1]

Ultimate goes to college – 1970

The first collegiate ultimate club was formed by Joel Silver when he arrived at Lafayette College in 1970 [2].

The first intercollegiate competition was held at Rutgers' New Brunswick campus between Rutgers and Princeton on November 6, 1972, the 103rd anniversary of the first intercollegiate game of American football featuring the same schools competing in the same location.

By 1975, dozens of colleges had teams, and in April of that year players organized the first ever ultimate tournament, an eight-team invitational called the "Intercollegiate Ultimate Frisbee Championships," to be played at Yale. Rutgers beat Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), 26-23, in the finals.

By 1976, teams were popping up in areas outside the Northeast. A 16-team single elimination tournament was set up, at Amherst, Massachusetts, to include 13 East Coast teams and 3 Midwest teams. Rutgers again took the title, beating Hampshire College in the finals. Penn State and Princeton were the other semi-finalists. While it was called the "National Ultimate Frisbee Championships", ultimate was starting to appear in the Los Angeles and Santa Barbara area.

Penn State hosted the first five-region National Ultimate Championships in May of 1979. There were five regional representatives, three college and two club teams. They were as follows: Cornell University-(Northeast), Glassboro State-(Middle Atlantic), Michigan State-(Central), Orlando Fling-(South), Santa Barbara Condors-(West). Each team played the other in a round robin format to produce a Glassboro-Condors final. The Condors had gone undefeated up to this point, however Glassboro prevailed 19-18 to become the 1979 National Champions. They repeated as champions in 1980 as well.

Ultimate spreads to clubs and internationally – 1976

In California clubs were sprouting in the LA - Santa Barbara area, while in the east, where the game developed at the high school and college level, the first college graduates were beginning to found club teams, such as the Philadelphia Frisbee Club, the Washington Area Frisbee Club, the Knights of Nee in NJ, the Hostages in Boston and so forth.

In the same year, ultimate arrived in the United Kingdom, with clubs forming at the University of Warwick, University of Southampton, University of Cambridge, University of Leicester, and University of Bradford.

Ultimate gets organized – the UPA – 1979–80

In 1979 and 1980 the Ultimate Players Association (www.upa.org) was formed. The UPA organized regional tournaments and has crowned a national champion every year since 1979.

The popularity of the game quickly spread, taking hold as a free-spirited alternative to traditional organized sports. In recent years college ultimate has attracted a greater number of traditional athletes, raising the level of competition and athleticism, and providing a challenge to its laid back, free-spirited roots.

Rules of play

There are two sets of nearly identical rules in common use: the UPA rules used in North America and the WFDF rules used in all other parts of the world. The two rule sets are mostly the same with some minor differences. The section provides an overview of the rules that are common between both sets. For more specifics see the websites of the relevant organizations listed at the bottom of article.

Objective

The objective of ultimate is to score points by receiving a teammate's pass in the opponent's endzone. (One could of course argue that this is only a secondary goal, and the primary goal is to have fun and a good time; in many tournaments, the "Spirit of the Game" award (see below) is just as valued as winning the finals.) The outcome of a match is usually determined by one team achieving a predetermined number of points first. This ensures that a team can only win by scoring, rather than by running the clock down. However, in most styles of competitive play, if game time runs beyond a certain time limit (preset by tournament host), a "soft cap" is first called, which announces 10 minutes until the "hard cap," where the game ends as soon as the point being played finishes.

Teams

Regulation ultimate is played between two teams of seven players. In informal "pick-up" games, the number of players varies. Substitutions are allowed between points and teams are usually able to have around 20 players on their roster in a major tournament. A shortage of players may force teams to play the entire game without substitutions, a condition known as savage or ironman.

Field

Regulation games are played on a field of 70 yards (64 meters) by 40 yards (37 meters). Under UPA rules, endzones are 25 yards (23 meters) deep, while under WFDF rules, endzones are 18 meters deep. Normally, ultimate is played outdoors on grass. Boundaries are marked by chalklines and cones.

Indoor

Ultimate is sometimes played on an indoor soccer field, or the like. If the field has indoor soccer markings on it, then the outer most goal box lines are used for endzone lines. Playing off the walls or ceiling is usually not permitted. As indoor venues tend to be smaller, the number of players per side is often decreased, usually to 5-a-side.

In some indoor leagues, Quebec City rules are used in order to speed up play. For example:

- Only 2 pulls every game: at the beginning of the game and after halftime. Each team pulls once.

- After a point is scored, play resumes from the end zone where the point was scored.

- Minimum two passes required to score a point after a score.

- Maximum 20 second delay between the scoring of a point and the beginning of the next one.

- Players may only sub on and off the field between points.

- Each team is allowed one timeout per game.

- Timeouts cannot be called in the last 5 minutes of the game.

Indoor ultimate is played widely in Northern Europe during the winter due to frigid weather conditions.

In North America, indoor ultimate tends to be played in venues that can accommodate a field of regular or near-regular size and the playing surface is AstroTurf or some other kind of artificial grass.

In Europe, on the other hand, such facilities are rarely available and indoor ultimate is usually played five-a-side on a handball or basketball court. Northern European and Scandinavian countries usually use handball courts, whereas in the UK, Russia, and Southern Europe basketball courts are more commonly used, presumably because there are few handball courts available in those countries. Players often wear protection such as knee, elbow and wrist pads, much like in volleyball to avoid bruises and cuts when laying out.

European indoor ultimate has evolved as a variant of standard outdoor ultimate. Due to the small size of the court and of the absence of wind, several indoor-specific offensive and defensive tactics have been developed. Moreover, throws such as scoobers, blades, hammers, and push-passes are rarely used or discouraged outdoors because even a little wind makes them inaccurate or because they are effective only at short range, but they are common in the small and wind-free indoor courts. The stall count is reduced to 8 seconds due to the faster nature of the indoor game.

There are regular indoor tournaments and championships and stable indoor teams. The best-known and longest-running indoor tournament is the Skogshyddan's Vintertrofén held in Gothenburg, Sweden every year.

Beach ultimate

Beach ultimate is a variant of the sport. It is played in teams of four or five players on small fields. It is played on sand and, as the name implies, normally at the beach. Players usually play barefoot or wearing sand shoes. BULA (Beach Ultimate Lovers Association) is the international governing body for beach ultimate.

Most beach ultimate tournaments are played according to BULA rules, which take elements of both UPA and WFDF rules.

Gameplay

The pull or throw-off

The players line up at the edge of their respective endzones, and the defensive team throws, or pulls, the disc to the offensive team to begin play. Pulls are normally long, hanging throws, giving the defense an opportunity to move up the field. Sometimes, though, a pull consists of a short throw intended to roll out of bounds upon hitting the ground.

The pull is often started by a member of the defending team raising one arm with the disc to show that they are ready to pull the disc and begin play. When the offensive team is ready to receive the pull, one of its members will also raise a hand.

The team that pulls to start the game is usually decided in a manner similar to a coin toss.

Movement of the disc

The disc may be moved in any direction by completing a pass to a teammate. A player catching the disc must stop after a few steps to run out their momentum, and can only move their non-pivot foot. A common misconception is that a player must setup a pivot foot before they can throw the disc. In fact, the player can throw the disc before stopping within the first couple of steps after they gain possession of the disc. It is this fact that makes the "Greatest" rule possible. A "Greatest" occurs when a player jumps from within bounds to catch a disc that has passed out-of-bounds. The player must then throw the disc back in-bounds before his feet or any other part of his body touches the ground. The thrower may only catch their own throw if another player touches it in the air.

Upon receiving the disc, a player has ten seconds to pass it. This period is known as the "stall", and each second is counted out (a stall count) by a defender (the marker), who must be standing within three meters of the thrower. A player may keep the disc for longer than ten seconds if no marker is within three meters, or if the marker is not counting the stall; if there is a change of marker, the new marker must restart the stall from zero.

Scoring

A point is scored when a player catches a pass in the endzone his team is attacking. In older versions of the rules, only offensive players could score. However, current UPA and WFDF rules allow a defensive team to score by intercepting a pass in the endzone they are attacking. This play is referred to as a Callahan goal or simply a Callahan. It is named after well-known ultimate player Henry Callahan.

After a point is scored, the teams exchange ends. The team who just scored remains in that endzone and the opposing team takes the opposite endzone. Play is re-initiated with a pull by the scoring team.

Change of possession

An incomplete pass results in a change of possession. When this happens the defense immediately becomes the offense and gains possession of the disc where it comes to a stop on the field of play, or where it first traveled out of bounds. Play does not stop due to a turnover.

Reasons for turnovers:

- Throw-away – The thrower misses his target and the disc falls to the ground.

- Drops – The receiver is not able to catch the disc.

- Blocks – A defender deflects the disc in mid flight, causing it to hit the ground.

- Interceptions – A defender catches a disc thrown by the offense.

- Out of Bounds – The disc lands out of bounds, hits an object out of bounds or is caught by a player who lands or leaps from outside the playing field.

- Stalls – A player on offense does not release the disc after the defender has counted out ten seconds.

Stoppages of play

Play may stop for the following reasons:

Fouls

A foul is the result of contact between players, although incidental contact (not affecting the play) does not constitute a foul. When a foul disrupts possession, the play resumes as if the possession were retained. If the player committing the foul disagrees with ("contests") the foul call, the disc is returned to the last thrower.

Violations

A violation occurs when a player violates the rules but does not initiate physical contact. Common violations include traveling with the disc, double teaming, stripping the disc away from a player who has possession, and picking, or moving in a manner so as to obstruct the movement of any player on the defensive team.

Time outs and half-time

By Tenth Edition rules, each team is allowed two time outs per half. The halftime break occurs when one team reaches the half-way marker in the score. Since most games are played to odd numbers, the number for half-time is rounded up. For instance, if the game is to 13, half comes when one team scores 7.

Injuries

Play stops whenever a player is injured—this is considered an injury time-out. During the duration, it is customary for players on the field to kneel or sit to ensure that they stay in their original positions. The injured person must then leave the field, and a substitute may come in. If an injured player is substituted for, the opposing team may also substitute a player. A substitution is not required if the injury was due to an opposing player or if the team decides to also be charged with a team time-out.

Substitutions

Teams are allowed to substitute players after a point is scored or for injured players after an injury time out. In the case of an injury substitution, the opposing team is allowed to make a substitution for a non-injured player.

Refereeing

Players are responsible for foul and line calls. Players resolve their own disputes. This creates a spirit of honesty and respect on the playing field. It is the duty of the player who committed the foul to speak up and admit his infraction. Occasionally, official observers are used to aid players in refereeing (see below).

Observers

Some additional rules have been introduced which can optionally overlay the standard rules and allow for referees called observers (the Tenth Edition, X-Rules or Callahan Rules, named after Henry Callahan from the University of Oregon). An observer can only resolve a dispute if the players involved ask for his judgment. Although, in some cases, observers have the power to make calls without being asked: e.g. line calls (to determine out of bounds or goals) and off-sides calls (players crossing their end zone line before the pull is released). Misconduct fouls can also be given by an observer for violations such as aggressive taunting, fighting, cheating, etc., and are reminiscent of the Yellow/Red card system in soccer; however, misconduct fouls are extremely rare and their ramifications not well defined. Observers are also charged with enforcing time limits for the game itself and many parts within the game, such as the amount of time defense has to set up after a time out or the time allowed between pulls, are honored.

The introduction of observers is, in part, an attempt by the UPA to allow games to run more smoothly and become more spectator-friendly. Due to the nature of play and the unique nature of self-refereeing, ultimate games are often subject to regular and long stoppages of play. This effort and the intensity that has arisen in the highest levels of competition have led many members of the ultimate community to lament the loss of the Spirit of the Game. It should be noted that some of the differences between the UPA and the WFDF rules reflect a differing attitude to spirit.

Strategy and tactics

Offensive strategies

Teams employ many different offensive strategies with different goals. Most basic strategies are an attempt to create open lanes on the field for the exchange of the disc between the thrower and the receiver. Organized teams assign positions to the players based on their specific strengths. Designated throwers are called handlers and designated receivers are called cutters. The amount of autonomy or overlap between these positions depends on the make-up of the team

One of the most common offensive strategies is the vertical stack. In this strategy, the offense lines up in a straight line along the length of the field. From this position, players in the stack make cuts (sudden sprints out of the stack) towards or away from the handler in an attempt to get open and receive the disc. The stack generally lines up in the middle of the field, thereby opening up two lanes along the sidelines for cuts, although a captain may occasionally call for the stack to line up closer to one sideline, leaving open just one larger cutting lane on the other side. In the college game, the vertical stack is more prevalent on the East Coast.

Another popular offensive strategy is the horizontal stack. In the most popular form of this offense, three handlers line up across the width of the field with four cutters upfield, also lined up across the field. It is the handler's job to throw the disc upfield to the cutters. If no upfield options are available, the handlers swing the disc side to side in an attempt to reset the stall count while also getting the defense out of position. In the college game, the horizontal stack is used frequently in the Midwest.

Many advanced teams develop specific offenses that are variations on the basics in order to take advantage of the strengths of specific players. Frequently, these offenses are meant to isolate a few key players in one-on-one situations, allowing them more freedom of movement and the ability to make most of the plays, while the others play a supporting role.

Players making cuts have two majors options in how they cut. They may cut in towards the disc and attempt to find an open avenue between defenders for a short pass, or they may cut away from the disc towards the deep field. The deep field is usually sparsely-defended but requires the handler to throw a huck (a long downfield throw).

Defensive strategies

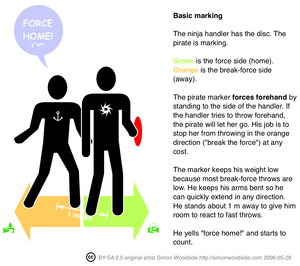

One of the most basic defensive principles is the force. The marker effectively cuts off the handler's access to half of the field, by aggressively blocking only one side of the handler and leaving the other side open. The unguarded side is called the force side because the thrower is generally forced to throw to that side of the field. The guarded side is called the break-force side because the thrower would have to "break" the force in order to throw to that side – a difficult feat.

The reason this is done is that with evenly matched players, the advantage is almost always with the handler and against the marker. It is relatively easy for the handler to fake out or outmaneuver a marker who is trying to block the whole field. On the other hand, it is generally possible to effectively block half of the field.

The marker calls out the force side ("force home" or "force away") before starting the stall count in order to alert the other defenders which side of the field is open to the handler. The team can choose the force side ahead of time, or change it on the fly from throw to throw. Aside from forcing home or away, other forces are "force sideline" (force towards the closest sideline), "force center" (force towards the center of the field), and "force up" (force towards either sideline but prevent a throw straight up the field). Another common tactic is to "force forehand" (force the thrower to use their forehand throw) since most players, especially at lower levels of play, have a stronger backhand throw. "Force flick" refers to the forehand; "force back" refers to the backhand.

When the marker calls out the force side, the team can then rely on the marker to block off half the field and position themselves to aggressively cover just the open/force side. If they are playing one-to-one defense, they should position themselves on the force side of their marks, since that is the side that they are most likely to cut to.

The simplest and often most effective defensive strategy is the one-on-one defense (also known as man-on-man or just man), where each defender guards a specific offensive player, called their "mark". The one-on-one defense emphasizes speed, stamina, and individual positioning and reading of the field. Often players will mark the same person throughout the game, giving them an opportunity to pick up on their opponent's strengths and weaknesses as they play. One-on-one defense can also play a part role in other more complex zone defense strategies.

Zone defense

With a zone defense strategy, the defenders cover an area rather than a specific person. The area they cover moves with the disc as it progresses down the field. Zone defense is frequently used when the other team is substantially more athletic (faster) making one-on-one difficult to keep up with, because it requires less speed and stamina. It's also useful in a long tournament to avoid tiring out the team, or when it is very windy and long passes are out of the question.

A zone defense usually has two components. The first is a group of players close to the handler(s) who attempt to contain the disc and prevent forward movement, called the wedge, cup, wall, or clam (depending on the specific play). These close defenders always position themselves relative to the disc, meaning that they have to move quickly as it passes from handler to handler.

The wedge is a configuration of two close defenders. One of them marks the handler with a force, and the other stands away and to the force side of the handler, blocking any throw or cut on that side. The wedge allows more defenders to play up the field, but does little to prevent cross-field passes (such as a swing).

The cup involves three players, arranged in a semi-circular cup-shaped formation, one in the middle and back, the other two on the sides and forward. One of the side players marks the handler with a force, while the other two guard the open side. Therefore the handler will normally have to throw into the cup, allowing the defenders to more easily make blocks. With a cup, usually the center cup blocks the up-field lane to cutters, while the side cup blocks the cross-field swing pass to other handlers. The center cup usually also has the responsibility to call out which of the two sides should mark the thrower, usually the defender closest to the sideline of the field.

The wall involves four players in the close defense. One players is the marker, also called the "rabbit" or "chaser" because they often have to run quickly between multiple handlers spread out across the field. The other three defenders form a horizontal "wall" or line across the field in front of the handler to stop throws to cuts and prevent forward progress.

The players in the second group of a zone defense, called mids and deeps, position themselves further out to stop throws that escape the cup and fly upfield. Because a zone defense focuses defenders on stopping short passes, it leaves a large portion of the field to be covered by the remaining mid and deep players. Assuming that there are seven players on the field, and that a cup is in effect, this leaves four players to cover the rest of the field. In fact, usually only one deep player is used to cover hucks, with two others defending the sidelines and possibly a single "mid-mid".

Alternately, the mids and deeps can play a one-to-one defense on the players who are outside of the cup or cutting deep, although frequent switching might be necessary.

One final zone defense strategy, known as the Clam or Chrome Wall, uses elements of both zone and man defenses. In Clam defenses, defenders cover cutting lanes rather than zones of the field or individual players. The Clam can be used by several players on a team while the rest are running a man defense. This defensive strategy is often referred to as Bait and Switch. In this case, when the two players the defenders are covering are standing close to each other in the stack, one defender will move over to shade them deep, and the other will move slightly more towards the thrower. When one of the receivers makes a deep cut, the first defender picks them up, and if one makes an in-cut, the second defender covers them. The defenders communicate, and switch their marks if their respective charges change their cuts from in to deep, or vice versa. The Clam can also be used by the entire team, with different defenders covering in cuts, deep cuts, break side cuts, and dump cuts.

The exact configuration of both groups depends on the specific style of zone defense, and there are wide variations. One of the advantages of knowing a number of zone defense styles is to confuse the opposing team by switching or using an unknown style.

Spirit of the game

Ultimate is known for its "Spirit of the Game", often abbreviated SOTGS. The following description is from the official ultimate rules established by the Ultimate Players Association:

Ultimate has traditionally relied upon a spirit of sportsmanship which places the responsibility for fair play on the player. Highly competitive play is encouraged, but never at the expense of the bond of mutual respect between players, adherence to the agreed upon rules of the game, or the basic joy of play. Protection of these vital elements serves to eliminate adverse conduct from the Ultimate field. Such actions as taunting of opposing players, dangerous aggression, intentional fouling, or other 'win-at-all-costs' behavior are contrary to the spirit of the game and must be avoided by all players.

Many tournaments give awards for the most spirited team, as voted for by all the teams taking part in the tournament. This honor, sometimes called the Spirit Award, is highly regarded.

Cheers

At some levels of competition, it is still customary for teams to cheer their opponent at the end of the game. This tradition is an example of how the spirit of ultimate differs from most other sports, as these cheers are meant to be ridiculous, fun, and amusing. Cheers are often creative, and can take the form of a short game involving both teams (very often involving a disc), or possibly a song. Cheers are known as calls in the U.K. Cheers are less common at the higher levels of play, although attitudes towards this custom vary between countries and organizations.

Pick-up games

In the spirit of ultimate's egalitarian roots, there are many types of pick-up. Often this consists of tournaments played outside the championship circuit, including hat tournaments, in which teams are selected on the day of play by picking names out of a hat. These are generally held over a weekend, affording players several games during the day as well as the chance to socialize and party at night. Pick-up leagues also exist, hosting weekly pick-up games that may be played on arbitrary week nights. In addition, less formal games of pick-up are frequent in parks and fields across the globe. In all these types of pick-up games it will not be uncommon to have as participants the same people who play on nationally or globally competitive teams. Newcomers are always welcomed at pick-up games or whenever people are simply throwing, and enthusiastic players will sideline themselves to spend time teaching beginners the throws and maneuvers necessary to play.

UPA's worldwide pickup listing

Hat tournaments

Hat tournaments are common in the ultimate circuit. They are tournaments where players join individually rather than as a team. The tournament organizers form teams by randomly taking the names of the participants from a hat.

In practice, in most tournaments, the organizers do not actually use a hat, but form teams taking into account skill, experience, sex, age, height, and fitness level of the players in the attempt to form teams of even strength. A player provides this information when he or she signs up to enter the tournament.

Hat tournaments have a strong emphasis on having fun, socializing, partying, and meeting other players. Players of all levels take part to such events from world-class players to complete beginners.

Hat tournaments (and sometimes also regular tournaments) often have a theme, such as: wild west, aliens, pirates, superheroes, etc. The organizers often name teams also according to a theme, such as: beer varieties, movie characters, etc.

Current leagues

Regulation play, sanctioned in the United States by the UPA, occurs at the college (open & women's divisions), club (open, women's, mixed (co-ed), and masters divisions) and youth (boys & girls divisions) levels, with annual championships in all divisions. Top teams from the championship series compete in semi-annual world championships regulated by the WFDF, made up of national flying disc organizations and federations from about 50 countries.

Recreational leagues have become widespread, and range in organization and size. There have been a small number of children's leagues. The largest and first known pre-high school league was started in 1993 by Mary Lowry, Joe Bisignano, and Jeff Jorgenson in Seattle, Washington. In 2005, the DiscNW Middle School Spring League had over 450 players on 30 mixed teams. Large high school leagues are also becoming common. The largest one is the DiscNW High School Spring League. It has both mixed and single gender divisions with over 30 teams total. The largest adult league is the Ottawa-Carleton Ultimate Association, with 350 teams and over 4000 active members in 2005, located in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Dating back to 1976, the Mercer County (New Jersey) Ultimate Disc League (mcudl.org) is the world's oldest recreational league. [citation needed] There are even large leagues with children as young as third grade, an example being the Jr division of the SULA ultimate league in Amherst, MA, with a current size of 200 people.

High School and Junior Leagues

High School division teams have also gained popularity and awareness in the past few years. Tournaments at the high school level of play range from tournaments hosted by local teams to tournaments at a national level. The UPA hosts the Men and Women's HS national championships every year in two locations, allowing them to split the championships between East and West coast teams. These two tournaments, affectionately known as Eastern's and Western's, are becoming extremely competitive as High School programs are beginning to treat the sport of ultimate more and more seriously. The UPA also hosts a national Junior's club team tournament and sends a representative team to the World Junior Ultimate Championships, held every two years. At a lower level, the UPA has also sanctioned organized statewide tournaments in 16 states.

Some youth powerhouses include The Paideia School Gruel, The Amherst Regional High School Hurricanes, and the varsity team from the Northwest. In 2007, Paideia Gruel finished with the highest RRI of any youth team.

College teams

There are over 600 college ultimate teams in North America and the number of teams is steadily growing. Separated into Open (nearly 450 teams) and Women's (around 200 teams) Divisions, teams compete in the UPA Championship series during the Spring. The series consists of 3 tournaments: Sectionals, Regionals, and Nationals. Each year, the sectional and regional champions advance to Nationals to compete for the Championship title in May.

Club Teams

UPA Club ultimate consists of Open, Women's, Masters, Youth and Mixed divisions. Teams are listed on the UPA's team listing page.

Terms

For descriptions of various types of throws, see disc throws.

To see the list of Ultimate Frisbee terms see Ultimate Terms.

Major tournaments

- World Ultimate & Guts Championships (WUGC), international tournament attended by national teams; organized by the WFDF. 2008 tournament link.

- World Ultimate Club Championships (WUCC), international tournament attended by club teams; organized by the WFDF. 2006 tournament link.

- European Ultimate Championships (EUC), European tournament attended by national teams; organized by the EFDF. 2007 tournament link.

- World Junior Ultimate Championships (WJUC), international tournament attended by national junior teams; organized by the WFDF. 2006 tournament link.

- UPA Championship Series, an American and Canadian tournament series attended by regional teams; organized by the UPA. Championship Series link.

- April Fools Fest, the longest continuously running tournament in Ultimate history (30th anniversary 2006); organized by WAFC.2006 tournament link

- Potlatch, the largest mixed ultimate tournament in the world; organized by DiscNW.2006 tournament link

- Canadian Ultimate Championship, Canada's national tournament series attended by regional division qualifiers; organized by CUPA.2006 tournament link

- Windmill Windup, The Dutch Windmill Windup tourney with both an open and a women's division (largest women's division in Europe)hosts teams from all over Europe. With revolutionary Swiss-Draw format; organized by. 2007 tournament link

- Wonderful Copenhagen Ultimate, The Danish WCU tourney with both an open and a women's division hosts teams from all over Europe and even some from the US or asia. 2007 tournament link

Beach Ultimate

- Paganello, unofficial Beach Ultimate world cup, held every year on Easter weekend in Rimini, Italy.

- Burla Beach Cup. A large tournament, in 2006 hosted 70 teams, held every year in September in Viareggio, Tuscany, Italy. Organized by the Tuscan Flying Bisch Association.

- World Championship Beach Ultimate 2007 (WCBU2007) . The 2nd 5-on-5 Beach Ultimate World Championship for national teams. Will be held in December 2007 in Brazil. Organized by Federação Paulista de Disco with the collaboration of BULA.

- [3] CUBE Caledonia's Ultimate Beach Event. The University of Aberdeen's BULA affiliated open beach ultimate competition held annually in April.

References

See also

External links

Resources for players

- Ultipedia.org - the Ultimate wiki

- The Ultimate Handbook

- The old Ultimate Handbook (content that is not in the new one)

- The old Ultimate Handbook (PDF)

- Ultimate Lingo (glossary)

- Ultimate Talk (blog aggregator)

- PlayUltimate (high school ultimate news and commentary)

- Ultimate History Book

- Diagrams, rulebook, and throwing styles

- rec.sport.disc (discussion forum for Ultimate and other disc sports)

Rules

- The Complete 11th Edition of the Rules of Ultimate, Approved 01/11/2007 (for Americas)

- WFDF rules (for rest of world and Worlds championship)

Leagues and associations

International

- The World Flying Disc Federation Homepage

- The Beach Ultimate Lovers Association Homepage

- European Flying Disc Federation Homepage

- UK and Ireland Ladder League

National

- Australian Flying Disc Association

- The Canadian Ultimate Players Association Homepage

- Finnish Flying Disc Association

- French Flying Disc Federation - FFDF

- Irish Flying Disc Association

- Mexican Flying Disc Federation Homepage

- Philippine Ultimate Association Homepage

- Singapore Ultimate

- South African Flying Disc Association

- UK Ultimate Association

- The Ultimate Players Association Homepage (USA)

- Italian Flying Disc Federation

- New Zealand Ultimate

- The Hong Kong Ultimate Players' Association

- Swiss Frisbee Sport Federation

- Korea Ultimate (Korean Run)

- Korea Ultimate Players Association (WFDF recognized group)

- Beach Ultimate Group - Portugal

- Dutch Frisbee Bond

- German Frisbee Association

- Russian Flying Disc Federation