Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were nuclear attacks during World War II against the Empire of Japan by the United States of America under US President Harry S. Truman. On August 6, 1945, the nuclear weapon "Little Boy" was dropped on the city of Hiroshima (広島市, Hiroshima-shi), followed on August 9, 1945 by the detonation of the "Fat Man" nuclear bomb over Nagasaki (長崎市, Nagasaki-shi). They are the only instances of the use of nuclear weapons in warfare.

In estimating the number of deaths caused by the attacks, there are several factors that make it difficult to arrive at reliable figures: inadequacies in the records given the confusion of the times, the small number who died months or years after the bombing as a result of radiation exposure, and the pressure to either exaggerate or minimize the numbers, depending upon political agenda. That said, it is estimated that as many as 140,000 had died in Hiroshima by the bomb and its associated effects,[1][2][3] with the estimate for Nagasaki roughly 74,000.[4] Almost all of the casualties were a direct result of the bomb itself, with very few people dying from radiation induced illnesses [5]. In both cities, the overwhelming majority of the deaths were those of civilians.

The role of the bombings in Japan's surrender, as well as the effects and justification of them, has been subject to much debate.

On August 15, 1945 Japan announced its surrender to the Allied Powers, signing the Instrument of Surrender on September 2 which officially ended World War II. Furthermore, the experience of bombing led post-war Japan to adopt Three Non-Nuclear Principles, which forbids Japan from nuclear armament.

The Manhattan Project

The United States, with assistance from the United Kingdom and Canada, designed and built the first atomic bombs under what was called the Manhattan Project. The project was initially started at the instigation of European refugee scientists (including Albert Einstein) and American scientists who feared that Nazi Germany would also be conducting a full-scale bomb development program (that program was later discovered to be much smaller and further behind). The project itself eventually employed over 130,000 people at its peak at over thirty institutions spread over the United States, and cost a total of nearly US$2 billion, making it one of the largest and most costly research and development programs of all time.

The first nuclear device, called "Gadget," was detonated during the "Trinity" test near Alamogordo, New Mexico on July 16, 1945. The Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs were the second and third to be detonated and as of 2007 the only ones ever detonated in a military action. (See Weapons of Mass Destruction.)

During World War II both the Allies and Axis powers had previously pursued policies of strategic bombing and the targeting of civilian infrastructure. In numerous cases these had caused huge numbers of civilian casualties and were (or came to be) controversial. In Germany, the Allied firebombing of Dresden resulted in roughly 30,000 deaths. The March 1945 firebombing of Tokyo killed 72,489 people, according to the Japan War History office.[6] By August, about 60 Japanese cities had been destroyed through a massive aerial campaign, including massive firebombing raids on the cities of Tokyo and Kobe.

Over 3½ years of direct U.S. involvement in World War II, approximately 290,000 Americans had been killed in action and another 110,000 killed as a result of the war,[7] 90,000 of them incurred in the war against Japan.[8] In the months prior to the bombings, the Battle of Okinawa resulted in an estimated 50,000–150,000 civilian deaths, 100,000–125,000 Japanese or Okinawan military or conscript deaths and over 72,000 American casualties.[citation needed] Deathtoll was given as 107,539 counted dead plus an estimated 23,764 in the closed caves or buried by the Japanese. Since the number was far above the estimated Japanese force on the island the army intelligence supposed that about 42,000 was civilians.[9] A commonly provided justification for the bombings is that an invasion of the Japanese mainland was expected to result in casualties many times greater than in Okinawa.

U.S. President Harry S. Truman was unaware of the Manhattan Project until Franklin Roosevelt's death. Truman asked U.S. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson to head a group of prominent citizens called the Interim Committee, which included three respected scientists and had been set up to advise the President on the military, political, and scientific questions raised by the possible use of the first atomic bomb. On May 31, Stimson put his conclusions to the committee and a four-man Scientific Panel. Stimson supported use of the bomb, stating "Our great task is to bring this war to a prompt and successful conclusion." But Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, one of the Scientific Panel members, stated that a single atomic bomb would probably kill twenty thousand people, and the target should be a military one, not civilian. Another scientist, Dr. Arthur Holly Compton, suggested dropping the bomb on an isolated part of Japan to demonstrate its power while minimizing civilian deaths. But this was soon dismissed, since if Japan was to be notified in advance of an attack, the bomber might be shot down; alternately, the first bomb might fail to detonate.[10]

In early July, on the way to Potsdam, Truman re-examined the decision to use the bomb. In the end, Truman made the decision to drop the atomic bombs on Japan. His stated intention in ordering the bombings was to bring about a quick resolution of the war by inflicting destruction, and instilling fear of further destruction, that was sufficient to cause Japan to surrender.

On July 26, Truman and other allied leaders issued The Potsdam Declaration outlining terms of surrender for Japan:

- "...The might that now converges on Japan is immeasurably greater than that which, when applied to the resisting Nazis, necessarily laid waste to the lands, the industry and the method of life of the whole German people. The full application of our military power, backed by our resolve, will mean the inevitable and complete destruction of the Japanese armed forces and just as inevitably the utter devastation of the Japanese homeland..."

- "...We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction."

The next day, Japanese papers reported that the declaration, the text of which had been broadcast and dropped on leaflets into Japan, had been rejected. The atomic bomb was still a highly guarded secret and not mentioned in the declaration. The government of Japan showed no intention of accepting the ultimatum. On July 28, Prime Minister Suzuki Kantaro declared at a press conference that the Potsdam Declaration was no more than a rehash (yakinaoshi) of the Cairo Declaration and that the government intended to ignore it (mokusatsu).

Emperor Hirohito, who was waiting for a Soviet reply to noncommittal Japanese peace feelers, made no move to change the government position.[11] On July 31, he made clear to Kido that the Imperial Regalia of Japan had to be defended at all costs.[12]

Choice of targets

The Target Committee at Los Alamos on May 10–11, 1945, recommended Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, and the arsenal at Kokura as possible targets. The committee rejected the use of the weapon against a strictly military objective because of the chance of missing a small target not surrounded by a larger urban area. The psychological effects on Japan were of great importance to the committee members. They also agreed that the initial use of the weapon should be sufficiently spectacular for its importance to be internationally recognized. The committee felt Kyoto, as an intellectual center of Japan, had a population "better able to appreciate the significance of the weapon." Hiroshima was chosen because of its large size, its being "an important army depot" and the potential that the bomb would cause greater destruction because the city was surrounded by hills which would have a "focusing effect".[13]

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson struck Kyoto from the list because of its cultural significance, over the objections of General Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project. According to Professor Edwin O. Reischauer, Stimson "had known and admired Kyoto ever since his honeymoon there several decades earlier." On July 25 General Carl Spaatz was ordered to bomb one of the targets: Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, or Nagasaki as soon after August 3 as weather permitted and the remaining cities as additional weapons became available.[14]

Hiroshima

Hiroshima during World War II

At the time of its bombing, Hiroshima was a city of some industrial and military significance. A number of military camps were located nearby, including the headquarters of the Fifth Division and Field Marshal Shunroku Hata's 2nd General Army Headquarters, which commanded the defense of all of southern Japan. Hiroshima was a minor supply and logistics base for the Japanese military. The city was a communications center, a storage point, and an assembly area for troops. It was one of several Japanese cities left deliberately untouched by American bombing, allowing an ideal environment to measure the damage caused by the atomic bomb. Another account stresses that after General Spaatz reported that Hiroshima was the only targeted city without prisoner of war (POW) camps, Washington decided to assign it highest priority.

The center of the city contained several reinforced concrete buildings and lighter structures. Outside the center, the area was congested by a dense collection of small wooden workshops set among Japanese houses. A few larger industrial plants lay near the outskirts of the city. The houses were of wooden construction with tile roofs, and many of the industrial buildings also were of wood frame construction. The city as a whole was highly susceptible to fire damage.

The population of Hiroshima had reached a peak of over 381,000 earlier in the war, but prior to the atomic bombing the population had steadily decreased because of a systematic evacuation ordered by the Japanese government. At the time of the attack the population was approximately 255,000. This figure is based on the registered population used by the Japanese in computing ration quantities, and the estimates of additional workers and troops who were brought into the city may be inaccurate.

The bombing

- For composition of USAAF mission see 509th Composite Group

Hiroshima was the primary target of the first nuclear bombing mission on August 6, with Kokura and Nagasaki being alternative targets. August 6 was chosen because there had previously been cloud over the target. The B-29 Enola Gay, piloted and commanded by 509th Composite Group commander Colonel Paul Tibbets, was launched from North Field airbase on Tinian in the West Pacific, about six hours flight time from Japan. The Enola Gay (named after Colonel Tibbets' mother) was accompanied by two other B29s, The Great Artiste which carried instrumentation, commanded by Major Charles W. Sweeney, and a then-nameless aircraft later called Necessary Evil (the photography aircraft) commanded by Captain George Marquardt.[15]

After leaving Tinian the aircraft made their own individual way to Iwo Jima where they rendezvoused at 2440 m (8000 ft) and set course for Japan. The aircraft arrived over the target in clear visibility at 9855 m (32,000 ft). On the journey, Navy Captain William Parsons had armed the bomb, which had been left unarmed to minimize the risks during takeoff. His assistant, 2nd Lt. Morris Jeppson, removed the safety devices 30 minutes before reaching the target area.[15]

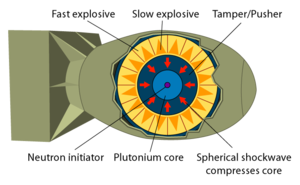

The release at 08:15 (Hiroshima time) was uneventful, and the gravity bomb known as "Little Boy", a gun-type fission weapon with 60 kg (130 pounds) of uranium-235, took 57 seconds to fall from the aircraft to the predetermined detonation height about 600 meters (2,000 ft) above the city. It created a blast equivalent to about 13 kilotons of TNT (the U-235 weapon was considered very inefficient, with only 1.38% of its material fissioning),[16]The radius of total destruction was about 1.6 km (1 mile), with resulting fires across 11.4 km² (4.4 square miles).[17] Infrastructure damage was estimated at 90 percent of Hiroshima's buildings being either damaged or completely destroyed.

About an hour before the bombing, Japanese early warning radar detected the approach of some American aircraft headed for the southern part of Japan. An alert was given and radio broadcasting stopped in many cities, among them Hiroshima. At nearly 08:00, the radar operator in Hiroshima determined that the number of planes coming in was very small—probably not more than three—and the air raid alert was lifted. To conserve fuel and aircraft, the Japanese had decided not to intercept small formations. The normal radio broadcast warning was given to the people that it might be advisable to go to air-raid shelters if B-29s were actually sighted, but no raid was expected beyond some sort of reconnaissance.

As a result of the blast an estimated minimum 90,000 people died within two months.[18] Included in this number were about 2,000 Japanese Americans and another 800-1,000 who lived on as hibakusha, a Japanese term meaning, "explosion-affected people". As US citizens, many were attending school before the war and had been unable to leave Japan.[19] It is likely that hundreds of Allied prisoners of war also died.[20]

Japanese realization of the bombing

The Tokyo control operator of the Japanese Broadcasting Corporation noticed that the Hiroshima station had gone off the air. He tried to re-establish his program by using another telephone line, but it too had failed. [21] About twenty minutes later the Tokyo railroad telegraph center realized that the main line telegraph had stopped working just north of Hiroshima. From some small railway stops within 16 kilometers (10 mi) of the city came unofficial and confused reports of a terrible explosion in Hiroshima. All these reports were transmitted to the headquarters of the Japanese General Staff.

Military bases repeatedly tried to call the Army Control Station in Hiroshima. The complete silence from that city puzzled the men at headquarters; they knew that no large enemy raid had occurred and that no sizable store of explosives was in Hiroshima at that time. A young officer of the Japanese General Staff was instructed to fly immediately to Hiroshima, to land, survey the damage, and return to Tokyo with reliable information for the staff. It was generally felt at headquarters that nothing serious had taken place and that it was all a rumor.

The staff officer went to the airport and took off for the southwest. After flying for about three hours, while still nearly 100 miles (160 km) from Hiroshima, he and his pilot saw a great cloud of smoke from the bomb. In the bright afternoon, the remains of Hiroshima were burning. Their plane soon reached the city, around which they circled in disbelief. A great scar on the land still burning and covered by a heavy cloud of smoke was all that was left. They landed south of the city, and the staff officer, after reporting to Tokyo, immediately began to organize relief measures.

Tokyo's first knowledge of what had really caused the disaster came from the White House public announcement in Washington, D.C., sixteen hours after the nuclear attack on Hiroshima.[22]

By August 8, 1945, newspapers in the US were reporting that broadcasts from Radio Tokyo had described the destruction observed in Hiroshima. "Practically all living things, human and animal, were literally seared to death," Japanese radio announcers said in a broadcast captured by Allied sources. [23]

Post-attack casualties

By December of 1945, thousands had died from their injuries and a small number from radiation poisoning, bringing the total killed in Hiroshima in 1945 to perhaps 140,000.[24] In the years between 1950 and 1990, it is statistically estimated that hundreds of deaths are attributable to radiation exposure among atomic bomb survivors from both Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[25][26]

Survival of some structures

Some of the reinforced concrete buildings in Hiroshima were very strongly constructed because of the earthquake danger in Japan, and their framework did not collapse even though they were fairly close to the center of damage in the city. Akiko Takakura was among the closest survivors to the hypocenter of the blast. She had been in the strongly built Bank of Hiroshima only 300m from ground-zero at the time of the attack. [27] Since the bomb detonated in the air, the blast was more downward than sideways, which was largely responsible for the survival of the Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall, now commonly known as the Genbaku, or A-bomb Dome designed and built by the Czech architect Jan Letzel, which was only 150 meters (490 feet) from ground zero (the hypocenter). The ruin was named Hiroshima Peace Memorial and made a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1996 over the objections of the U.S. and China.[28]

Events of August 7-9

After the Hiroshima bombing, President Truman announced, "If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air the likes of which has never been seen on this earth." On August 8 1945, leaflets were dropped and warnings were given to Japan by Radio Saipan. (The area of Nagasaki did not receive warning leaflets until August 10, though the leaflet campaign covering the whole country was over a month into its operations.)[29][30]

The Japanese government still did not react to the Potsdam Declaration. Emperor Hirohito, the government and the War council were considering four conditions for surrender : the preservation of the kokutai (Imperial institution and national polity), assumption by the Imperial Headquarters of responsibility for disarmament and demobilization, no occupation and delegation to the Japanese government of the punishment of war criminals.

The Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov informed Tokyo of the Soviet Union's unilateral abrogation of the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact on April 5. At two minutes past midnight on August 9, Tokyo time, Soviet infantry, armor, and air forces launched an invasion of Manchuria. Four hours later, word reached Tokyo that the Soviet Union had declared war on Japan. The senior leadership of the Japanese Army began preparations to impose martial law on the nation, with the support of Minister of War Anami, in order to stop anyone attempting to make peace.

Responsibility for the timing of the second bombing was delegated to Colonel Tibbets as commander of the 509th Composite Group on Tinian. Scheduled for August 11 against Kokura, the raid was moved forward to avoid a five day period of bad weather forecast to begin on August 10.[31] Three bomb pre-assemblies had been transported to Tinian, labeled F-31, F-32, and F-33 on their exteriors. On August 8 a dress rehearsal was conducted off Tinian by Maj. Charles Sweeney using Bockscar as the drop airplane. Assembly F-33 was expended testing the components and F-31 was designated for the mission August 9.[32]

Nagasaki

Nagasaki during World War II

The city of Nagasaki had been one of the largest sea ports in southern Japan and was of great wartime importance because of its wide-ranging industrial activity, including the production of ordnance, ships, military equipment, and other war materials.

In contrast to many modern aspects of Hiroshima, the bulk of the residences were of old-fashioned Japanese construction, consisting of wood or wood-frame buildings, with wood walls (with or without plaster), and tile roofs. Many of the smaller industries and business establishments were also housed in buildings of wood or other materials not designed to withstand explosions. Nagasaki had been permitted to grow for many years without conforming to any definite city zoning plan; residences were erected adjacent to factory buildings and to each other almost as closely as possible throughout the entire industrial valley.

Nagasaki had never been subjected to large-scale bombing prior to the explosion of a nuclear weapon there. On August 1 1945, however, a number of conventional high-explosive bombs were dropped on the city. A few hit in the shipyards and dock areas in the southwest portion of the city, several hit the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works and six bombs landed at the Nagasaki Medical School and Hospital, with three direct hits on buildings there. While the damage from these bombs was relatively small, it created considerable concern in Nagasaki and many people—principally school children—were evacuated to rural areas for safety, thus reducing the population in the city at the time of the nuclear attack.

To the north of Nagasaki there was a camp holding British Commonwealth prisoners of war, some of whom were working in the coal mines and only found out about the bombing when they came to the surface. At least eight known POWs died from the bombing.[33]

The bombing

- For composition of USAAF mission see 509th Composite Group

On the morning of August 9 1945, the U.S. B-29 Superfortress Bockscar, flown by the crew of 393rd Squadron commander Major Charles W. Sweeney, carried the nuclear bomb code-named "Fat Man", with Kokura as the primary target and Nagasaki the secondary target. The mission plan for the second attack was nearly identical to that of the Hiroshima mission, with two B-29's flying an hour ahead as weather scouts and two additional B-29's in Sweeney's flight for instrumentation and photographic support of the mission. Sweeney took off with his weapon already armed but with the electrical safety plugs still engaged.[34]

Observers aboard the weather planes reported both targets clear. When Sweeney's aircraft arrived at the assembly point for his flight off the coast of Japan, the third plane (flown by the group's Operations Officer, Lt. Col. James I. Hopkins, Jr.) failed to make the rendezvous. Bockscar and the instrumentation plane circled for forty minutes without locating Hopkins. Already thirty minutes behind schedule, Sweeney decided to fly on without Hopkins.[34]

By the time they reached Kokura a half hour later, a 7/10 cloud cover had obscured the city, prohibiting the visual attack required by orders. After three runs over the city, and with fuel running low because a transfer pump on a reserve tank had failed before take-off, they headed for their secondary target, Nagasaki.[34] Fuel consumption calculations made en route indicated that Bockscar had insufficient fuel to reach Iwo Jima and they would be forced to divert to Okinawa. After initially deciding that if Nagasaki were obscured on their arrival they would carry the bomb to Okinawa and dispose of it in the ocean if necessary, the weaponeer Navy Commander Frederick Ashworth decided that a radar approach would be used if the target was obscured.[35]

At about 07:50 Japanese time, an air raid alert was sounded in Nagasaki, but the "all clear" signal was given at 08:30. When only two B-29 Superfortresses were sighted at 10:53, the Japanese apparently assumed that the planes were only on reconnaissance and no further alarm was given.

A few minutes later, at 11:00, the support B-29 flown by Captain Frederick C. Bock dropped instruments attached to three parachutes. These instruments also contained an unsigned letter to Professor Ryokichi Sagane, a nuclear physicist at the University of Tokyo who studied with three of the scientists responsible for the atomic bomb at the University of California, Berkeley, urging him to tell the public about the danger involved with these weapons of mass destruction. The messages were found by military authorities but not turned over to Sagane until a month later.[36] In 1949 one of the authors of the letter, Luis Alvarez, met with Sagane and signed the document. [37]

At 11:01, a last minute break in the clouds over Nagasaki allowed Bockscar's bombardier, Captain Kermit Beahan, to visually sight the target as ordered. The "Fat Man" weapon, containing a core of ~6.4 kg (14.1 lb) of plutonium-239, was dropped over the city's industrial valley. 43 seconds later it exploded 469 meters (1,540 ft) above the ground exactly halfway between the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works in the south and the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works (Torpedo Works) in the north. This was nearly 3 kilometers (2 mi) northwest of the planned hypocenter; the blast was confined to the Urakami Valley and a major portion of the city was protected by the intervening hills.[38] The resulting explosion had a blast yield equivalent to 21 kilotons of TNT. The explosion generated heat estimated at 7000 degrees Fahrenheit and winds that were estimated at 624 mph.

According to some estimates, about 70,000 of Nagasaki's 240,000 residents were killed instantly,[39] and up to 60,000 were injured. The radius of total destruction was about 1.6 km (1 mile), followed by fires across the northern portion of the city to 3.2 km (2 miles) south of the bomb.[40] The total number of residents killed may have been as many as 80,000, including the few who died from radiation poisoning in the following months.[41]

An unknown number of survivors from the Hiroshima bombing made their way to Nagasaki and were bombed again.[42][43]

Plans for more atomic attacks on Japan

The United States expected to have another atomic bomb ready for use in the third week of August, with three more in September and a further three in October.[44] On August 10, Major General Leslie Groves, military director of the Manhattan Project, sent a memorandum to General of the Army George Marshall, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, in which he wrote that "the next bomb . . should be ready for delivery on the first suitable weather after 17 or 18 August." On the same day, Marshall endorsed the memo with the comment, "It is not to be released over Japan without express authority from the President."[44] There was already discussion in the War Department about conserving the bombs in production until Operation Downfall, the projected invasion of Japan, had begun. "The problem now [13 August] is whether or not, assuming the Japanese do not capitulate, to continue dropping them every time one is made and shipped out there or whether to hold them . . . and then pour them all on in a reasonably short time. Not all in one day, but over a short period. And that also takes into consideration the target that we are after. In other words, should we not concentrate on targets that will be of the greatest assistance to an invasion rather than industry, morale, psychology, and the like? Nearer the tactical use rather than other use."[44]

The surrender of Japan and the U.S. occupation

Up to August 9, the War council was still insisting on its four conditions for surrender. On that day Hirohito ordered Kido to "quickly control the situation" "because Soviet Union has declared war against us". He then held an Imperial conference during which he authorized minister Togo to notify the Allies that Japan would accept their terms on one condition, that the declaration "does not compromise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a Sovereign ruler".[45]

On August 12, the Emperor informed the imperial family of his decision to surrender. One of his uncles, Prince Asaka, then asked whether the war would be continued if the kokutai could not be preserved. Hirohito simply replied "of course".[46] As the Allied terms seemed to leave intact the principle of the preservation of the Throne, Hirohito recorded on August 14 his capitulation announcement which was broadcast to the Japanese nation the next day despite a short rebellion by fanatic militarists opposed to the surrender.

In his declaration, Hirohito referred to the atomic bombings :

Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should We continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization. Such being the case, how are We to save the millions of Our subjects, or to atone Ourselves before the hallowed spirits of Our Imperial Ancestors? This is the reason why We have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of the Joint Declaration of the Powers.

However, in his "Rescript to the soldiers and sailors" delivered on 17 August, he stressed the impact of the Soviet invasion and his decision to surrender, omitting any mention of the bombs.

During the year after the bombing, approximately 40,000 U.S. occupation troops were in Hiroshima. Nagasaki was occupied by 27,000 troops.[47] Upper limit dose estimates for those troops range from 0.19–0.3 mSv for Hiroshima and from 0.8–6.3 mSv for Nagasaki, depending on location.[48]

The Hibakusha

The survivors of the bombings are called Hibakusha (被爆者), a Japanese word that literally translates to "explosion-affected people". The suffering of the bombing is the root of Japan's postwar pacifism, and the nation has sought the abolition of nuclear weapons from the world ever since. As of 2005, there are about 266,000 hibakusha still living in Japan.[49]

Korean survivors

During the war Japan brought many Korean conscripts to both Hiroshima and Nagasaki to work as forced labor. According to recent estimates, about 20,000 Koreans were killed in Hiroshima and about 2,000 died in Nagasaki. It is estimated that one in seven of the Hiroshima victims was of Korean ancestry.[50] For many years Koreans had a difficult time fighting for recognition as atomic bomb victims and were denied health benefits. [[9]] Though such issues have been somewhat addressed in recent years, issues and resentments regarding recognition continue to linger.

Debate over bombings

Support

Preferable to invasion

Those who argue in favor of the decision to drop the bombs generally assert that the bombings ended the war months sooner than would otherwise have been the case, thus saving many lives. It is argued that there would have been massive casualties on both sides in the impending Operation Downfall invasion of Japan,[51] and that even if Operation Downfall was postponed, the status quo of conventional bombings and the Japanese occupations in Asia were causing tremendous loss of life.

The Americans anticipated losing many soldiers in the planned invasion of Japan, although the actual number of expected fatalities and wounded is subject to some debate. It depends on the persistence and reliability of Japanese resistance, and whether the Allies would have invaded only Kyūshū in November 1945 or if a follow up Allied landing near Tokyo, projected for March 1946, would have been needed. Years after the war, Secretary of State James Byrnes claimed that 500,000 "American" lives would have been lost, however in the summer of 1945,[citation needed] U.S. military planners projected 20,000–110,000 combat deaths from the initial November 1945 invasion, with about three to four times that number wounded.[citation needed] (Total U.S. killed in action on all fronts in World War II in nearly four years of war was 292,000.[7])

Japan chose not to surrender

A nation historically suspicious of Western imperialism, Japanese military officials were unanimously opposed to any negotiations before the use of the atomic bomb. The rise of Japanese militarism in the wake of the Great Depression had resulted in countless assassinations of reformers attempting to check military power, such as those of Takahashi Korekiyo, Saitō Makoto, and Inukai Tsuyoshi, creating an environment in which opposition to war was itself a risky endeavor.[52]

While some members of the civilian leadership did use covert diplomatic channels to attempt peace negotiation, they could not negotiate surrender or even a cease-fire. Japan, as a Constitutional Monarchy, could only legally enter into a peace agreement with the unanimous support of the Japanese cabinet, and in the summer of 1945, the Japanese Supreme War Council, consisting of representatives of the Army, the Navy and the civilian government, could not reach a consensus on how to proceed.[52]

A political stalemate developed between the military and civilian leaders of Japan, the military increasingly determined to fight despite all costs and odds and the civilian leadership seeking a way to negotiate an end to the war. Further complicating the decision was the fact that no cabinet could exist without the representative of the Imperial Japanese Army. This meant that the Army could veto any decision by having its Minister resign, thus making it the most powerful post on the SWC. In early August of 1945 the cabinet was equally split between those who advocated an end to the war and those who would not surrender under any circumstances. The hawks consisted of General Korechika Anami, General Yoshijiro Umezu and Admiral Teijiro Toyoda and were led by Anami. The doves consisted of Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki, Naval Minister Mitsumasa Yonai,and Shigenori Togo and were led by Togo.[52]

The peace faction, led by Togo, seized on the bombing as decisive justification of surrender. Kōichi Kido, one of Emperor Hirohito's closest advisers, stated: "We of the peace party were assisted by the atomic bomb in our endeavor to end the war." Hisatsune Sakomizu, the chief Cabinet secretary in 1945, called the bombing "a golden opportunity given by heaven for Japan to end the war." The pro-peace civilian leadership was then able to use the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to convince the military that no amount of courage, skill, and fearless combat could help Japan against the power of atomic weapons. The cabinet made a unanimous decision to surrender and accept the terms of the Potsdam agreement.[52]

Speedy end of war saved lives

Supporters of the bombing also point out that waiting for the Japanese to surrender was not a cost-free option—as a result of the war, noncombatants were dying throughout Asia at a rate of about 200,000 per month.[citation needed] Firebombing had killed well over 100,000 people in Japan since February of 1945, directly and indirectly. That intensive conventional bombing would have continued prior to an invasion. The submarine blockade and the United States Army Air Forces's mining operation, Operation Starvation, had effectively cut off Japan's imports. A complementary operation against Japan's railways was about to begin, isolating the cities of southern Honshū from the food grown elsewhere in the Home Islands. "Immediately after the defeat, some estimated that 10 million people were likely to starve to death," noted historian Daikichi Irokawa. Meanwhile, in addition to the Soviet attacks, fighting continued in The Philippines, New Guinea and Borneo, and offensives were scheduled for September in southern China and Malaya.

The atomic bomb hastened the end of the war, liberating millions in occupied areas, including thousands of interned civilians and prisoners of war from Japanese camps. For example, in the case of the Dutch East Indies, these included about 200,000 Dutch and 400,000 Indonesians romusha (slave laborers). In Java alone, between four and 10 million romusha were forced to work by the Japanese military.[53] About 270,000 Javanese romusha were sent to other Japanese-held areas in South East Asia. Only 52,000 were repatriated to Java, meaning that there was a death rate of 80%.

Philippine justice Delfin Jaranillla, member of the Tokyo tribunal, wrote in his judgement that «If a means is justified by an end, the use of the atomic bomb was justified for it brought Japan to her knees and ended the horrible war. If the war had gone longer, without the use of the atomic bomb, how many thousands and thousands of helpless men, women and children would have needlessely died and suffer ...? [54]

Moreover, Japanese troops had committed atrocities against millions of civilians, by means including the sanko sakusen ("scorched earth") policies, the infamous Nanking Massacre and the use of chemical and bacteriological weapons, and the early end to the war prevented further bloodshed. Millions of Asian civilians died of famine under Japanese rule: for example, a UN report states that four million people died in the Dutch East Indies as a result of famine and forced labor during the Japanese occupation, including 30,000 European civilian internee deaths.[55] These war crimes were ongoing, and use of the atomic bombs brought them to an abrupt end.

Supporters also point to an order given by the Japanese War Ministry on August 1, 1944, ordering the disposal and execution of all Allied POWs, numbering over 100,000, if an invasion of the Japanese mainland took place.[56]

Part of "total war"

Supporters of the bombings have argued that the Japanese government waged total war, ordering many civilians (including women and children) to work in factories and military offices and to fight against any invading force. Father John A. Siemes, professor of modern philosophy at Tokyo's Catholic University, and an eyewitness to the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima wrote:

- "We have discussed among ourselves the ethics of the use of the bomb. Some consider it in the same category as poison gas and were against its use on a civil population. Others were of the view that in total war, as carried on in Japan, there was no difference between civilians and soldiers, and that the bomb itself was an effective force tending to end the bloodshed, warning Japan to surrender and thus to avoid total destruction. It seems logical to me that he who supports total war in principle cannot complain of war against civilians."[57]

Some supporters of the bombings have emphasized the strategic significance of Hiroshima, as the Japanese 2nd army's headquarters, and of Nagasaki, as a major munitions manufacturing center.

In his speech to the Japanese people presenting his reasons for surrender, Emperor Hirohito refered specifically to the atomic bombs, stating that if they continued to fight it would result in "...an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation..."[58] In his first ever press conference given in Tokyo in 1975, Hirohito was asked what he thought of the bombing of Hiroshima. He answered : «It's very regrettable that nuclear bombds were dropped and I feel sorry for the citizens of Hiroshima but it couldn't be helped because that happened in wartime.» [59]

Opposition

Inherently immoral

A number of notable individuals and organizations have criticized the bombings, many of them characterizing them as war crimes or crime against humanity. Two early critics of the bombings were Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard, who had together spurred the first bomb research in 1939 with a jointly written letter to President Roosevelt. Szilard, who had gone on to play a major role in the Manhattan Project, argued:

- "Let me say only this much to the moral issue involved: Suppose Germany had developed two bombs before we had any bombs. And suppose Germany had dropped one bomb, say, on Rochester and the other on Buffalo, and then having run out of bombs she would have lost the war. Can anyone doubt that we would then have defined the dropping of atomic bombs on cities as a war crime, and that we would have sentenced the Germans who were guilty of this crime to death at Nuremberg and hanged them?"[60]

A number of scientists who worked on the bomb were against its use. Led by Dr. James Franck, seven scientists submitted a report to the Interim Committee (which advised the President) in May 1945, saying:

- "If the United States were to be the first to release this new means of indiscriminate destruction upon mankind, she would sacrifice public support throughout the world, precipitate the race for armaments, and prejudice the possibility of reaching an international agreement on the future control of such weapons."[61]

On August 8, 1945, Albert Camus addressed the bombing of Hiroshima in an editorial in the French newspaper Combat:

- "Mechanized civilization has just reached the ultimate stage of barbarism. In a near future, we will have to choose between mass suicide and intelligent use of scientific conquests[...] This can no longer be simply a prayer; it must become an order which goes upward from the peoples to the governments, an order to make a definitive choice between hell and reason."[62]

In 1946, a report by the Federal Council of Churches entitled Atomic Warfare and the Christian Faith, includes the following passage:

- "As American Christians, we are deeply penitent for the irresponsible use already made of the atomic bomb. We are agreed that, whatever be one's judgment of the war in principle, the surprise bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are morally indefensible."

In 1963 the bombings were the subject of a judicial review in Ryuichi Shimoda et al. v. The State.[63] On the 22nd anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the District Court of Tokyo declined to rule on the legality of nuclear weapons in general, but found that "the attacks upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki caused such severe and indiscriminate suffering that they did violate the most basic legal principles governing the conduct of war."[64]

In the opinion of the court, the act of dropping an atomic bomb on cities was at the time governed by international law found in the Hague Regulations on Land Warfare of 1907 and the Hague Draft Rules of Air Warfare of 1922–1923[65] and was therefore illegal.[66]

As the first military use of nuclear weapons, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki represent to some the crossing of a crucial barrier. Peter Kuznick, director of the Nuclear Studies Institute at American University in Washington DC wrote of President Truman:

- ”He knew he was beginning the process of annihilation of the species. It was not just a war crime; it was a crime against humanity."[67]

Kurznick is one of several observers who believe that the U.S. was largely motivated in carrying out the bombings by a desire to demonstrate the power of its new weapon to the Soviet Union. Historian Mark Selden of Cornell University has stated "Impressing Russia was more important than ending the war in Japan."[67]

Takashi Hiraoka, mayor of Hiroshima, upholding nuclear disarmament, said in a hearing to The Hague International Court of Justice (ICJ):

- "It is clear that the use of nuclear weapons, which cause indiscriminate mass murder that leaves [effects on] survivors for decades, is a violation of international law".[68][69]

Iccho Itoh, the mayor of Nagasaki, declared in the same hearing:

- "It is said that the descendants of the atomic bomb survivors will have to be monitored for several generations to clarify the genetic impact, which means that the descendants will live in anxiety for [decades] to come. [...] with their colossal power and capacity for slaughter and destruction, nuclear weapons make no distinction between combatants and non-combatants or between military installations and civilian communities [...] The use of nuclear weapons [...] therefore is a manifest infraction of international law."[68]

John Bolton, former US ambassador to the United Nations, used Hiroshima and Nagasaki as examples why the US should not adhere to the International Criminal Court (ICC):

- "A fair reading of the treaty [the Rome Statute concerning the ICC], for example, leaves the objective observer unable to answer with confidence whether the United States was guilty of war crimes for its aerial bombing campaigns over Germany and Japan in World War II. Indeed, if anything, a straightforward reading of the language probably indicates that the court would find the United States guilty. A fortiori, these provisions seem to imply that the United States would have been guilty of a war crime for dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This is intolerable and unacceptable."[70]

Although bombings do not meet the definition of genocide, some consider that this definition is too strict, and that these bombings do represent a genocide.[71][72] For example, University of Chicago historian Bruce Cumings states there is a consensus among historians to Martin Sherwin's statement, that "the Nagasaki bomb was gratuitous at best and genocidal at worst."[73]

Militarily unnecessary

Those who argue that the bombings were unnecessary on military grounds hold that Japan was already essentially defeated and ready to surrender.

One of the most notable individuals with this opinion was then-General Dwight D. Eisenhower. He wrote in his memoir The White House Years:

- "In 1945 Secretary of War Stimson, visiting my headquarters in Germany, informed me that our government was preparing to drop an atomic bomb on Japan. I was one of those who felt that there were a number of cogent reasons to question the wisdom of such an act. During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives."[74][75]

Other U.S. military officers who disagreed with the necessity of the bombings include General Douglas MacArthur (the highest-ranking officer in the Pacific Theater), Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy (the Chief of Staff to the President), General Carl Spaatz (commander of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific), and Brigadier General Carter Clarke (the military intelligence officer who prepared intercepted Japanese cables for U.S. officials),[75] and Admiral Ernest King, U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, Undersecretary of the Navy Ralph A. Bard,[76] and Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet.[77]

- "The Japanese had, in fact, already sued for peace. The atomic bomb played no decisive part, from a purely military point of view, in the defeat of Japan." Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet.[78]

- "The use of [the atomic bombs] at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender." Admiral William D. Leahy, Chief of Staff to President Truman.[78]

The United States Strategic Bombing Survey, after interviewing hundreds of Japanese civilian and military leaders after Japan surrendered, reported:

- "Based on a detailed investigation of all the facts, and supported by the testimony of the surviving Japanese leaders involved, it is the Survey's opinion that certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated."[79][78]

The survey assumed that continued conventional bombing attacks on Japan—with additional direct and indirect casualties—would be needed to force surrender by the November or December dates mentioned.

Many, including General MacArthur, have contended that Japan would have surrendered before the bombings if the U.S. had notified Japan that it would accept a surrender that allowed Emperor Hirohito to keep his position as titular leader of Japan, a condition the U.S. did in fact allow after Japan surrendered. U.S. leadership knew this, through intercepts of encoded Japanese messages, but refused to clarify Washington's willingness to accept this condition. Before the bombings, the position of the Japanese leadership with regards to surrender was divided. Several diplomats favored surrender, while the leaders of the Japanese military voiced a commitment to fighting a "decisive battle" on Kyūshū, hoping that they could negotiate better terms for an armistice afterward. The Japanese government did not decide what terms, beyond preservation of an imperial system, they would have accepted to end the war; as late as August 9, the Supreme War Council was still split, with the hard-liners insisting Japan should demobilize its own forces, no war crimes trials would be conducted, and no occupation of Japan would be allowed. Only the direct intervention of the emperor ended the dispute, and even then a military coup was attempted to prevent the surrender.

Historian Tsuyoshi Hasegawa's research has led him to conclude that the atomic bombings themselves were not even the principal reason for capitulation. Instead, he contends, it was the swift and devastating Soviet victories in Manchuria that forced the Japanese surrender on August 15 1945.[80]

Cultural references

- The book Hiroshima Mon Amour, by Marguerite Duras, and the related film, were partly inspired by the bombing. The film version, directed by Alain Resnais, has some documentary footage of the afteraffects, burn victims, devastation.

- The Japanese manga "Hadashi no Gen" ("Barefoot Gen"), also known as "Gen of Hiroshima";[10] Studio Ghibli's anime film Grave of the Fireflies which depicts American fire bombings in Japan; and Akira Kurosawa's Rhapsody in August are just a few examples from manga and film which deal with the bombings and/or the wartime context of the bombings.

- The musical piece "Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima" by Krzysztof Penderecki (sometimes also called Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima for 52 Strings, and originally 8'37" as a nod to John Cage) was written in 1960 as a reaction to what the composer believed to be a senseless act. On the 12th of October, 1964, Penderecki wrote: "Let the Threnody express my firm belief that the sacrifice of Hiroshima will never be forgotten and lost."

- Composer Robert Steadman has written a musical work for voice and chamber ensemble entitled Hibakusha Songs. Commissioned by the Imperial War Museum North, Manchester, it was premiered in 2005.

- Artists Stephen Moore and Ann Rosenthal examine 60 years of living in the shadow of the bomb in their decade-long art project "Infinity City." Their web site http://infcty.net documents their travels to historical sites on three continents and explores their art installations and web works reflecting on America's nuclear legacy.

- The Canadian progressive rock band Rush performed a song called "The Manhattan Project" depicting the events of and leading up to the bombing of Hiroshima.

- The story of Sadako Sasaki, a young Hiroshima survivor diagnosed with leukemia, has been recounted in a number of books and films. Two of the best known of these works are Karl Bruckner's Sadako will leben (1961), translated into 22 languages and Eleanor Coerr's Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes (Putnam, 1977). Sasaki, confined to a hospital because of her leukemia, created over 1,000 origami cranes, in reference to a Japanese legend which granted the creator of the cranes one wish.

- Native American novelist Gerald Vizenor`s "kabuki novel", Hiroshima Bugi (2003), compares the aftermath of the Hiroshima bombing to the aftermath of the conquest of the Americas.

- The Japanese author Fumiyo Kouno wrote her graphic novel about a story of a family after the atomic bomb, Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms (2004), and translated into some languages.

- The rock band Wishful Thinking had a hit in 1971 with "Hiroshima", a song about the bombing.

- The Japanese rock band L'Arc~en~Ciel recorded the song "Hoshizora" ("Starlit Sky") on the 2005 "Awake" album using Hiroshima as a metaphor of the devastation of war. The song was also dedicated to the victims of war in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Films about the events

- Kuroi ame ([[Black Rain (Japanese film)|Black Rain]]) (Feature-length drama). Japan. 1989.

{{cite AV media}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|director=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|distributor=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help)- The story of the aftermath of the Hiroshima bombing, based on Masuji Ibuse's novel. - Hiroshima (Feature-length docudrama). Canada/Japan. 1995.

{{cite AV media}}: Unknown parameter|director=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|distributor=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help)- A detailed, semi-documentary dramatisation of the political decisions involved with the atomic bombings. - Hachi-gatsu no kyôshikyoku ([[Rhapsody in August]]) (Feature-length drama). Japan. 1991.

{{cite AV media}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|director=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|distributor=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help)- Fictional drama that takes place in Nagasaki at the time of the bombing. - Hadashi no Gen (Barefoot Gen) (Feature-length, animated movie). Japan. 2005.

{{cite AV media}}: Unknown parameter|director=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|distributor=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help)- Animated dramatization of the bombing of Hiroshima based on the writer's own experiences and the documented experiences of other surivors.

See also

- Hiroshima Peace Memorial

- Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

- Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony

- Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims

- Hiroshima City Ebayama Museum of Meteorology

- Hiroshima Witness

- Children's Peace Monument

- Nagasaki Peace Park

- Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum

- Urakami Cathedral

- Aerial bombing of cities

- Strategic bombing

- The United States and nuclear weapons

- The United States and weapons of mass destruction

- Bombing of Tokyo in World War II

- Japanese atomic program

- Victor's justice

- Japanese war crimes

- World War II casualties

- Nuclear-free zone

References

- Sadao Asada (1997). "The Mushroom Cloud and National Psyches: Japanese and American Perceptions of the Atomic-Bomb Decision, 1945-1995". In Laura Hein and Mark Selden, eds. (ed.). Living with the Bomb: American and Japanese Cultural Conflicts in the Nuclear Age. East Gate Book. p. 186. ISBN 1-56324-967-7.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); External link in|title= - Herbert Bix (1996). "Japan's Delayed Surrender: A Reinterpretation". In Michael J. Hogan, ed. (ed.). Hiroshima in History and Memory. Cambridge University Press. p. 290. ISBN 0-521-56682-7.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Richard H. Campbell (2005). "Chapter 2: Development and Production". The Silverplate Bombers: A History and Registry of the Enola Gay and Other B-29s Configured to Carry Atomic Bombs. McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. p.114. ISBN 0-7864-2139-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Dower, John (1995). "The Bombed: Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japanese Memory". Diplomatic History. Vol. 19 (no. 2).

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help) - Jack Edwards Banzi you Bastards, Souviner Press, (paperback 1994), ISBN 0-285-63027-X, Page 260

- Eisenhower, Dwight D (1963). The White House Years; Mandate For Change: 1953-1956. Doubleday & Company. pp. pp. 312-313.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Falk, Richard A. (1965-02-15). "The Claimants of Hiroshima". The Nation.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) reprinted in Richard A. Falk, Saul H. Mendlovitz eds., ed. (1966). "The Shimoda Case: Challenge and Response". The Strategy of World Order. Volume: 1. New York: World Law Fund. pp. pp. 307-13.{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help);|pages=has extra text (help) - Richard B. Frank (2001). Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. Penguin Publishing. ISBN 0-679-41424-X.

- Freeman, Robert (2006). "Was the Atomic Bombing of Japan Necessary?". CommonDreams.org.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Frey, Robert S. (2004). The Genocidal Temptation: Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Rwanda and Beyond. University Press of America. ISBN 0761827439. Reviewed at: Rice, Sarah (2005). "The Genocidal Temptation: Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Rwanda and Beyond (Review)". Harvard Human Rights Journal. Vol. 18.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Mikiso Hane (2001). Modern Japan: A Historical Survey. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3756-9.

- Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi (2005). Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. Belknap Press. pp. pages 129, 298–299. ISBN 0-674-01693-9.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Lillian Hoddeson, et al, Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943-1945 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), on 295.

- The Spirit of Hiroshima: An Introduction to the Atomic Bomb Tragedy. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. 1999.

{{cite book}}: External link in|publisher= - The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II, A Collection of Primary Sources, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 162.

- Martin J. Sherwin (2003). A World Destroyed: Hiroshima and its Legacies (2nd edition ed.). Stanford University Press. pp. 233–234.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Kido Koichi nikki, Tokyo, Daigaku Shuppankai, 1966, p.1223, p.1120-1121

- Rinjiro Sodei. Were We the Enemy?: American Survivors of Hiroshima. Boulder: Westview Press, 1998

- John A. Siemes. "The Avalon Project : The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Chapter 25 - Eyewitness Account".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "United States Strategic Bombing Survey; Summary Report". United States Government Printing Office. 1946. pp. pg. 26.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Dennis D. Wainstock (1996). The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb. Praeger. p. 92. ISBN 0-275-95475-7.

Further reading

There is an extensive body of literature concerning the bombings, the decision to use the bombs, and the surrender of Japan. The following sources provide a sampling of prominent works on this subject matter. Because the debate over justification for the bombings is particularly intense, some of the literature may contain claims that are disputed.

- Hein, Laura and Selden, Mark (Editors) (1997). Living with the Bomb: American and Japanese Cultural Conflicts in the Nuclear Age. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 1-56324-967-9.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sherwin, Martin J. (2003). A World Destroyed: Hiroshima and its Legacies. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3957-9.

- Newman, Robert (2004). Enola Gay and the Court of History (Frontiers in Political Communication). Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 0-8204-7457-6.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. (1963). The White House Years; Mandate For Change: 1953-1956. Doubleday & Company.

- Craven, Wesley Frank (1946). "United States Strategic Bombing Survey; Summary Report (Pacific War)". The Army Air Forces in World War II. U.S. Government Printing Office.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, official homepage.

- Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, official homepage.

- Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims

- "Tale of Two Cities: The Story of Hiroshima and Nagasaki".

- "Documents on the Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb". The Harry S. Truman Library.

- "The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki". Manhattan Project, U.S. Army. 1946.

- Burr, William (Editor) (2005). "The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II: A Collection of Primary Sources". National Security Archive.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help)

Histories and descriptions

- Hoddeson, Lillian; et al. (1993). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44132-3.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - Sodei, Rinjiro (1998). Were We the Enemy? American Survivors of Hiroshima. Westview Press. ISBN 081333750X.

- Hachiya, Michihiko (1955). Hiroshima Diary. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4547-7.

- A daily diary covering the months after the bombing, written by a doctor who was in the city when the bomb was dropped.

- Hersey, John (1946, 1985). Hiroshima. Vintage Press. ISBN 0-679-72103-7.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

- An account of the bombing by an American journalist who visited the city shortly after the Occupation began, and interviewed survivors.

- Ogura, Toyofumi (1948). Letters from the End of the World: A Firsthand Account of the Bombing of Hiroshima. Kodansha International Ltd. ISBN 4-7700-2776-1.

- Sekimori, Gaynor (1986). Hibakusha: Survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Kosei Publishing Company. ISBN 4-333-01204-X.

- Selden, Kyoko; et al. (1986). The Atomic Bomb: Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Japan in the Modern World). M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 087332773X.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - Takashi, Nagai (1949). The Bells of Nagasaki. Kodansha International Ltd. ISBN 4-7700-1845-2.

- Weller, George and Weller, Anthony (2006). First Into Nagasaki: The Censored Eyewitness Dispatches on Post-Atomic Japan and Its Prisoners of War. Vintage Press. ISBN 0-307-34201-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lifton, Robert and Mitchell, Greg (1995). Hiroshima in America: A Half Century of Denial. Quill Publishing. ISBN 0-380-72764-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The Committee for the Compilation of Materials on Damage Caused by the Atomic Bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki (1981). Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Physical, Medical, and Social Effects of the Atomic Bombings. Basic Books. ISBN 046502985X.

- Detailed accounts of the immediate and subsequent casualties over three decades.

- Craig, William (1967). The Fall of Japan. Galahad Books. ISBN 0883659859.

- A history of the governmental decision making on both sides, the bombings, and the opening of the Occupation.

- Frank, Richard B. (2001). Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-100146-1.

- A history of the final months of the war, with emphasis on the preparations and prospects for the invasion of Japan. The author contends that the Japanese military leaders were preparing to continue the fight, and that they hoped that a bloody defense of their main islands would lead to something less than unconditional surrender and a continuation of their existing government.

- Hogan, Michael J. (1996). Hiroshima in History and Memory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521562066.

- Knebel, Fletcher and Bailey, Charles W. (1960). No High Ground. Harper and Row. ISBN 0313242216.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) A history of the bombings, and the decision-making to use them. - Robert Jungk, Brighter Than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1956, 1958)

- The Pacific War Research Society (2006). Japan's Longest Day. Oxford University Press. ISBN 4770028873.

- An account of the Japanese surrender and how it was almost thwarted by soldiers who attempted a coup against the Emperor.

- Rhodes, Richard (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671441337.

- Sweeney, Charles; et al. (1999). War's End: An Eyewitness Account of America's Last Atomic Mission. Quill Publishing. ISBN 0380788748.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Rhodes, Richard (1977). Enola Gay: The Bombing of Hiroshima. Konecky & Konecky. ISBN 1568525974.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help)

- A history of the preparations to drop the bombs, and of the missions.

- Walker, J. Samuel (1997). Prompt and Utter Destruction: President Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs Against Japan. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807823619.

- Walker, Stephen (2005). Shockwave: Countdown to Hiroshima. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0060742852.

- Narrative events in the lives of those involved in or touched by the bombings.

- Weintraub, Stanley (1995). The Last, Great Victory: The End of World War II. Truman Talley Books. ISBN 0525936874.

- Recounts the events day by day.

Online

- Hiroshima Memories by Americans who were there

- The Voice of Hibakusha

- Journalist George Weller's account of the aftermath at Nagasaki

- "The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki". U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey. 1946.

- Selden, Mark (2005). "Nagasaki 1945: While Independents Were Scorned, Embed Won Pulitzer". Yale Global Online.

- "Scientific Data of the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Disaster". Atomic Bomb Disease Institute, Nagasaki University. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

Debates over the bombings

- Wainstock, Dennis D. (1996). The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-95475-7.

- Grayling, A. C. (2006). Among the Dead Cities. Walker Publishing Company Inc. ISBN 0-8027-1471-4.

- Philosophical/moral discussion concerning the Allied strategy of area bombing in WWII, including the use of atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

- Allen, Thomas B. and Polmar, Norman (1995). Code-Name Downfall: The Secret Plan to Invade Japan And Why Truman Dropped the Bomb. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0684804069.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Concludes the bombings were justified.

- Alperovitz, Gar (1995). The Decision To Use The Atomic Bomb And The Architecture Of An American Myth. Knopf. ISBN 0679443312.

- Weighs whether the bombings were justified or necessary, concludes they were not.

- Bernstein, Barton J. (Editor) (1976). The Atomic Bomb: The Critical Issues. Little, Brown. ISBN 0316091928.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)

- Weighs whether the bombings were justified or necessary.

- Bird, Kai and Sherwin, Martin J. (2005). American Prometheus : The Triumph And Tragedy Of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Knopf. ISBN 0375412026.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "The thing had to be done," but "Circumstances are heavy with misgiving."

- Feis, Herbert (1961). Japan Subdued: The Atomic Bomb and the End of the War in the Pacific. Princeton University Press.

- Fussell, Paul (1988). Thank God For The Atom Bomb, And Other Essays. Summit Books. ISBN 0-345-36135-0.

- Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi (2005). Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. Belknap Press. ISBN 0674016939.

- Argues the bombs were not the deciding factor in ending the war. The Russian entrance into the Pacific war was the primary cause for Japan's surrender.

- Maddox, Robert James (1995). Weapons for Victory: The Hiroshima Decision. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0826215629.

- Author is diplomatic historian who favors Truman's decision to drop the atomic bombs.

- Newman, Robert P. (1995). Truman and the Hiroshima Cult. Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0870134035.

- An analysis critical of postwar opposition to the atom bombings.

- Nobile, Philip (Editor) (1995). Judgement at the Smithsonian. Marlowe and Company. ISBN 1569248419.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)

- Covers the controversy over the content of the 1995 Smithsonian Institution exhibition associated with the display of the Enola Gay; includes complete text of the planned (and canceled) exhibition.

- Takaki, Ronald (1995). Hiroshima: Why America Dropped the Atomic Bomb. Little, Brown. ISBN -316-83124-7.

Online

- Focuses on the evidence of recently released Japanese messages that the U.S. decrypted during the war.

- Edwards, Rob (2005). "Hiroshima bomb may have carried hidden agenda". New Scientist.

- Opinion article on findings suggesting Japan was already looking for peace, that it surrendered due to the Soviet invasion, and that Truman's true aim was to demonstrate US power to the Soviets.

- "The Fire Still Burns: An interview with historian Gar Alperovitz". Sojourners Magazine. 1995.

- Cooper, John W. (2000). "Truman's Motivations: Using the Atomic Bomb in the Second World War".

- Dannen, Gene (Editor) (2000). "Documents relating to the decision to use the atomic bomb".

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - "Correspondence Regarding Decision to Drop the Bomb". NuclearFiles.org.

- "The Decision To Use The Atomic Bomb; Gar Alperovitz And The H-Net Debate".

- Dietrich, Bill (1995). "Pro and Con on Dropping the Bomb". The Seattle Times.

- "Truman, The Bomb, And What Was Necessary". The Seattle Times. 1995.

- "Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered". 2005.

Footnotes

- ^ Japan's Asahi Shimbun estimates are 237,000 for Hiroshima, and 135,000 for Nagasaki including diseases from the aftereffects based on hospital data. The Spirit of Hiroshima: An Introduction to the Atomic Bomb Tragedy. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. 1999.

- ^ Mikiso Hane (2001). Modern Japan: A Historical Survey. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3756-9.

- ^ Possibly the most extensive review and analysis of the various death toll estimates is in: Richard B. Frank (2001). Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. Penguin Publishing. ISBN 0-679-41424-X.

- ^ "Nagasaki's Mayor Slams U.S. for Nuke Arsenal". Retrieved 2006-06-17.

- ^ Dose estimation for atomic bomb survivor studies: its evolution and present status Cullings HM, Fujita S, Funamoto S, Grant EJ, Kerr GD, Preston DL Radiat Res 166(1):219-54, 2006

- ^ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945, Random House, 1970, p. 676

- ^ a b Mathew White National Death Tolls for the Second World War: USA DoD: 291,557 KIA + 113,842 other = 405,399. White includes in addition there were about 9,300 Merchant Marine deaths. With the exception of Charles Messenger, The Chronological Atlas of World War Two that list an undifferentiated total of 300,000, all other sources in White's list are close to the DoD numbers.

- ^ Mathew White Campaigns: Pacific

- ^ Benis M. Frank "Okinava slutsteg mot segern" next to last page, Swedish translation of "Okinava: touchstone to victory"

- ^ John Toland, ibid, p. 762

- ^

Herbert Bix (1996). "Japan's Delayed Surrender: A Reinterpretation". In Michael J. Hogan, ed. (ed.). Hiroshima in History and Memory. Cambridge University Press. p. 290. ISBN 0-521-56682-7.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ Kido Koichi nikki, Tokyo, Daigaku Shuppankai, 1966, p.1120-1121

- ^ "Atomic Bomb: Decision — Target Committee, May 10–11, 1945".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Thomas Handy: Memorandum, July 25, 1945".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Timeline #2- the 509th; The Hiroshima Mission". Children of the Manhattan Project.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "SM15" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "The Bomb-"Little Boy"". The Atomic Heritage Foundation.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "RADIATION DOSE RECONSTRUCTION U.S. OCCUPATION FORCES IN HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI, JAPAN, 1945-1946 (DNA 5512F)" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "RERF Frequently Asked Questions".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Rinjiro Sodei. Were We the Enemy?: American Survivors of Hiroshima. Boulder: Westview Press, 1998

- ^ http://www.wagingpeace.org/articles/2005/08/20_rubin_remembering-normand-brissette.htm David Rubin, 2005, "Remembering Normand Brissette" (Downloaded 28/10/06)

- ^ "No High Ground by Knebel et al p175 to p201" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "White House Press Release on Hiroshima".

{{cite web}}: Text "Historical Documents" ignored (help); Text "The Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki" ignored (help); Text "atomicarchive.com" ignored (help) The press release, it should be noted, was written not by Truman but primarily by William L. Laurence, a New York Times reporter allowed access to the Manhattan Project. - ^ "Fulton Sun Retrospective".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The Spirit of Hiroshima: An Introduction to the Atomic Bomb Tragedy. Hiroshima: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, 1999.

- ^ "RERF Frequently Asked Questions".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "RERF Life Span Study Report 13".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Testimony of Akiko Takakura".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "unesco.org".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Studies in Intelligence".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "American Experience".

{{cite web}}: Text "Primary Sources" ignored (help); Text "Truman" ignored (help) - ^ Martin J. Sherwin (2003). A World Destroyed: Hiroshima and its Legacies (2nd edition ed.). Stanford University Press. pp. 233–234.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^

Richard H. Campbell (2005). "Chapter 2: Development and Production". The Silverplate Bombers: A History and Registry of the Enola Gay and Other B-29s Configured to Carry Atomic Bombs. McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. p.114. ISBN 0-7864-2139-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ As many as 13 POWs may have died in the Nagasaki bombing:

- 1 British Commonwealth ([1] [2]{Note last link reference use only.} (This last reference also lists at least three other POWS who died on 9-8-1945 [3][4][5]but does not tell if these were Nagasaki casualties)

- 7 Dutch {2 names known}[6] died in the bombing.

- At least 2 POWs reportedly died postwar from cancer thought to have been caused by Atomic bomb [7][8](note-last link United States Merchant Marine.org website).

- ^ a b c "Timeline #3- the 509th; The Nagasaki Mission". The Atomic Heritage Foundation.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Spitzer Personal Diary Page 25 (CGP-ASPI-025)". The Atomic Heritage Foundation.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Lillian Hoddeson, et al, Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943-1945 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), on 295.

- ^ "Stories from Riken" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonth=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Dennis D. Wainstock (1996). The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb. Praeger. p. 92.

- ^ Rinjiro Sodei. Were We the Enemy?: American Survivors of Hiroshima. Boulder: Westview Press, 1998, ix.

- ^ "Radiation Dose Reconstruction; U.S. Occupation Forces in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, 1945-1946 (DNA 5512F)" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Nagasaki marks tragic anniversary". People's Daily. 2005-08-10. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- ^ "'I saw both of the bombs and lived'". The Observer (reported in The Guardian). 2005-07-24. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- ^ Trumbull, Robert (1957). Nine Who Survived Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Tokyo, Japan: Tuttle Publishing.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ a b c

"The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II, A Collection of Primary Sources," (pdf). National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 162. The George Washington University. 1945-08-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Text "coauthors General Hull Colone Seazen" ignored (help) - ^ Kido Koichi nikki,Tokyo, Daigaku Shuppankai, 1966, p.1223

- ^ Terasaki Hidenari, Shôwa tennô dokuhakuroku, 1991, p.129

- ^ "DTRA Fact Sheets: Hiroshima and Nagasaki Occupation Forces".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ RADIATION DOSE RECONSTRUCTION U.S. OCCUPATION FORCES IN HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI, JAPAN, 1945-1946 (DNA 5512F)

- ^ "Asahi Shimbun, quoted by San Francisco Chronicle".