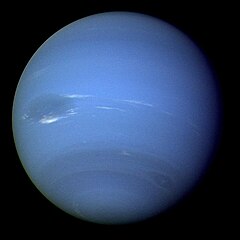

Neptune

Neptune from Voyager 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovered by | Urbain Le Verrier John Couch Adams Johann Galle | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery date | 1846-09-23 [1] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Adjectives | Neptunian | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Symbol | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Orbital characteristics[2][3] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Epoch J2000 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Aphelion | 4,553,946,490 km 30.44125206 AU | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Perihelion | 4,452,940,833 km 29.76607095 AU | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 4,503,443,661 km 30.10366151 AU | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.011214269 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 60,327.624 days 165.168034 yr | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 367.49 day[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||

Average orbital speed | 5.43 km/s[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 267.767281° | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Inclination | 1.767975° 6.43° to Sun's equator | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 131.794310° | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 265.646853° | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Known satellites | 13 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||||||||||||||

Equatorial radius | 24,764 ± 15 km[5][6] 3.883 Earths | ||||||||||||||||||||

Polar radius | 24,341 ± 30 km[5][6] 3.829 Earths | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Flattening | 0.0171 ± 0.0013 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 7.6408×109 km²[7][6] 14.94 Earths | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Volume | 6.254×1013 km³[4][6] 57.74 Earths | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mass | 1.0243×1026 kg[4] 17.147 Earths | ||||||||||||||||||||

Mean density | 1.638 g/cm³[4][6] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 11.15 m/s²[4][6] 1.14 g | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 23.5 km/s[4][6] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 0.6713 day[4] 16 h 6 min 36 s | |||||||||||||||||||||

Equatorial rotation velocity | 2.68 km/s 9,660 km/h | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 28.32°[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||

North pole right ascension | 17 h 19 min 59 s 299.333°[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||

North pole declination | 42.950°[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Albedo | 0.290 (bond) 0.41 (geom.)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 8.0 to 7.78 [4] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2.2" — 2.4" [4] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Atmosphere[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 19.7 ± 0.6 km | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Composition by volume |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Neptune (/ˈnɛptjuːn/) is the eighth planet from the Sun in the Solar System. It is the fourth largest planet by diameter, and the third largest by mass. Neptune is 17 times the mass of Earth and is slightly more massive than its near-twin Uranus, which is 14 Earth masses and less dense. The planet is named after the Roman god of the sea. Its astronomical symbol is ![]() , a stylized version of Poseidon's Trident.

, a stylized version of Poseidon's Trident.

Neptune's atmosphere is primarily composed of hydrogen and helium along with traces of methane. The methane in the atmosphere, in part, accounts for the planet's blue appearance, but because Neptune's colour is much more vivid than that of Uranus, which has a similar amount of methane, another component is presumed to contribute to Neptune's intense colour.[8] Neptune also has the strongest winds of any planet in the solar system, measured as high as 2,100 km/h.[9] At the time of the 1989 Voyager 2 flyby, it had in its southern hemisphere a Great Dark Spot comparable to the Great Red Spot on Jupiter. Neptune's temperature at its cloud tops is usually close to −218 °C, one of the coldest in the solar system, due to its great distance from the sun. The temperature in Neptune's centre is about 7,000 °C, which is comparable to the Sun's surface and similar to most other known planets.

Discovered on September 23, 1846,[1] Neptune was the first planet discovered by mathematical prediction rather than regular observation. Perturbations in the orbit of Uranus led astronomers to deduce Neptune's existence. It has been visited by only one spacecraft, Voyager 2, which flew by the planet on August 25, 1989. In 2003, there was a proposal to NASA's "Vision Missions Studies" to implement a "Neptune Orbiter with Probes" mission that does Cassini-level science without fission-based electric power or propulsion. The work is being done in conjunction with JPL and the California Institute of Technology.[10]

History

Discovery

Galileo's drawings show that he first observed Neptune on December 28, 1612, and again on January 27, 1613; on both occasions, Galileo mistook Neptune for a fixed star when it appeared very close (in conjunction) to Jupiter in the night sky.[11] Believing it to be a fixed star, he is not credited with its discovery. At the time of his first observation in December 1612, it was stationary in the sky because it had just turned retrograde that very day; because it was only beginning its yearly retrograde cycle, Neptune's motion was far too slight to be detected with Galileo's small telescope.[12]

In 1821, Alexis Bouvard published astronomical tables of the orbit of Uranus.[13] Subsequent observations revealed substantial deviations from the tables, leading Bouvard to hypothesize some perturbing body. In 1843, John Couch Adams calculated the orbit of an eighth planet that would account for Uranus' motion. He sent his calculations to Sir George Airy, the Astronomer Royal, who asked Adams for a clarification. Adams began to draft a reply but never sent it.

In 1846, Urbain Le Verrier, independently of Adams, produced his own calculations but also experienced difficulties in encouraging any enthusiasm in his compatriots. However, in the same year, John Herschel started to champion the mathematical approach and persuaded James Challis to search for the planet.

After much procrastination, Challis began his reluctant search in July 1846. However, in the meantime, Le Verrier had convinced Johann Gottfried Galle to search for the planet. Though still a student at the Berlin Observatory, Heinrich d'Arrest suggested that a recently drawn chart of the sky, in the region of Le Verrier's predicted location, could be compared with the current sky to seek the displacement characteristic of a planet, as opposed to a fixed star. Neptune was discovered that very night, September 23, 1846, within 1° of where Le Verrier had predicted it to be, and about 10° from Adams' prediction. Challis later realized that he had observed the planet twice in August, failing to identify it owing to his casual approach to the work.

In the wake of the discovery, there was much nationalistic rivalry between the French and the British over who had priority and deserved credit for the discovery. Eventually an international consensus emerged that both Le Verrier and Adams jointly deserved credit. However, the issue is now being re-evaluated by historians with the rediscovery in 1998 of the "Neptune papers" (historical documents from the Royal Greenwich Observatory), which had apparently been misappropriated by astronomer Olin Eggen for nearly three decades and were only rediscovered (in his possession) immediately after his death.[14] After reviewing the documents, some historians now suggest that Adams does not deserve equal credit with Le Verrier. [15]

Naming

Shortly after its discovery, Neptune was referred to simply as "the planet exterior to Uranus" or as "Le Verrier's planet". The first suggestion for a name came from Galle. He proposed the name Janus. In England, Challis put forth the name Oceanus. In France, Arago suggested that the new planet be called Leverrier, a suggestion which was met with stiff resistance outside France. French almanacs promptly reintroduced the name Herschel for Uranus and Leverrier for the new planet.

Meanwhile, on separate and independent occasions, Adams suggested altering the name Georgian to Uranus, while Le Verrier (through the Board of Longitude) suggested Neptune for the new planet. Struve came out in favor of that name on December 29, 1846, to the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences.[16] Soon Neptune became the internationally accepted nomenclature. In Roman mythology, Neptune was the god of the sea, identified with the Greek Poseidon. The demand for a mythological name seemed to be in keeping with the nomenclature of the other planets, all of which, except for Uranus, were named in antiquity.

The planet's name is translated literally as the sea king star in the Chinese,[17] Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese languages (海王星 in Chinese characters, 해왕성 in Korean).

In India the name given to the planet is Varuna (Devanāgarī: वरुण), the god of the sea in Vedic/Hindu mythology, the equivalent of Poseidon/Neptune in the Greco-Roman mythology.

Structure

Mass and composition

With a mass of 1.0243×1026 kg,[4] Neptune is an intermediate body between Earth and the largest gas giants: it is seventeen Earth masses but just 1/18th the mass of Jupiter. It and Uranus are often considered a sub-class of gas giant termed "ice giants", given their smaller size and important differences in composition relative to Jupiter and Saturn. In the search for extra-solar planets Neptune has been used as a metonym: discovered bodies of similar mass are often referred to as "Neptunes".[18] just as astronomers refer to various extra-solar "Jupiters."

The atmosphere of Neptune is composed primarily of hydrogen, with a smaller proportion of helium. A trace amount of methane is also present. Prominent absorption bands of methane occur at wavelengths above 600 nm, in the red and infrared portion of the spectrum. This absorption of red light by the atmospheric methane gives Neptune its blue hue.[19]

Orbiting so far from the sun, Neptune receives very little heat with the uppermost regions of the atmosphere at −218 °C (55 K). Deeper inside the layers of gas, however, the temperature rises steadily. As with Uranus, the source of this heating is unknown, but the discrepancy is larger: Neptune is the farthest planet from the Sun, yet its internal energy is sufficient to drive the fastest planetary winds seen in the Solar System. Several possible explanations have been suggested, including radiogenic heating from the planet's core,[20] the continued radiation into space of leftover heat generated by infalling matter during the planet's birth,[citation needed] and gravity waves breaking above the tropopause.[21][22]

The internal structure resembles that of Uranus. There is likely to be a core, believed to be of around 15 Earth masses, consisting of molten rock and metal surrounded by a mixture of rock, water, ammonia, and methane. As is customary in planetary science, this mixture is referred to as an ice even though it is a highly dense fluid. The atmosphere, extending perhaps 10 to 20% of the way towards the center, is mostly hydrogen and helium at high altitudes (80% and 19%, respectively). Increasing concentrations of methane, ammonia, and water are found in the lower regions of the atmosphere. Gradually this darker and hotter area blends into the superheated liquid interior. The pressure at the center of Neptune is millions of times more than that on the surface of Earth. Comparing its rotational speed to its degree of oblateness indicates that it has its mass less concentrated towards the center than does Uranus.

Weather and magnetic field

One difference between Neptune and Uranus is the typical level of meteorological activity. When the Voyager spacecraft flew by Uranus in 1986 that planet was visually quite bland, while Neptune exhibited notable weather phenomena during its 1989 Voyager fly-by. Neptune's atmosphere has the highest wind speeds in the solar system, thought to be powered by the flow of internal heat, and its weather is characterized by extremely dynamic storm systems, with winds reaching up to around 2,100 km/h, near-supersonic speeds. Even more typical winds in the banded equatorial region can possess speeds of around 1,200 km/h.[23]

In 1989, the Great Dark Spot, a cyclonic storm system the size of Eurasia, was discovered by NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft. The storm resembled the Great Red Spot of Jupiter. However, on November 2, 1994, the Hubble Space Telescope did not see the Great Dark Spot on the planet. Instead, a new storm similar to the Great Dark Spot was found in the planet's northern hemisphere. The reason for the Great Dark Spot's disappearance is unknown. One possible theory is that heat transfer from the planet's core disrupted the atmospheric equilibrium and disrupted existing circulation patterns.[citation needed] The Scooter is another storm, a white cloud group further south than the Great Dark Spot. Its nickname was bestowed when it was first detected in the months leading up to the Voyager encounter in 1989: it moved faster than the Great Dark Spot. Subsequent images showed clouds that moved even faster than Scooter. The Small Dark Spot is a southern cyclonic storm, the second most intensive storm during the 1989 encounter. It initially was completely dark, but as Voyager approached the planet, a bright core developed and is seen in most of the highest resolution images. In 2007 it was discovered that Neptune's south pole was about 10 °C warmer than the rest of Neptune which averages approximately −200 °C. The warmth differential is enough to let methane gas, which elsewhere lies frozen in Neptune's upper atmosphere, to leak out through the south pole and into space. The relative "hot spot" is due to Neptune's tilt in its orbit which has exposed the south pole to the Sun for the last 40 years, a Neptunian year being 165 Earth years. As Neptune slowly moves towards the sun, the south pole will be darkened and the north pole illuminated, causing the methane release to shift to the north pole. [24]

Unique among the gas giants is the presence of high clouds casting shadows on the opaque cloud deck below. Though Neptune's atmosphere is much more dynamic than that of Uranus, both planets are made of the same gases and ices. Uranus and Neptune are not strictly gas giants similar to Jupiter and Saturn, but are rather ice giants, meaning they have a larger solid core and are also made of ices. Neptune is very cold, with temperatures as low as −224 °C (49 K) recorded at the cloud tops in 1989.

Neptune also resembles Uranus in its magnetosphere, with a magnetic field strongly tilted relative to its rotational axis at 47° and offset at least 0.55 radii (about 13,500 kilometres) from the planet's physical centre. Comparing the magnetic fields of the two planets, scientists think the extreme orientation may be characteristic of flows in the interior of the planet and not the result of Uranus' sideways orientation.

Moons

Neptune has 13 known moons.[4] The largest by far, and the only one massive enough to be spheroidal, is Triton, discovered by William Lassell just 17 days after the discovery of Neptune itself. Unlike all other large planetary moons, Triton has a retrograde orbit, indicating that it was captured, and probably was once a Kuiper Belt object. It is close enough to Neptune to be locked into a synchronous orbit, and is slowly spiraling inward and eventually will be torn apart when it reaches the Roche limit. Triton is the coldest object that has been measured in the solar system, with temperatures of −235 °C (38 K).

| Triton, compared to Earth's Moon | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name |

Diameter (km) |

Mass (kg) |

Orbital radius (km) | Orbital period (days) | |

| Triton | ˈtraɪtən | 2700 (80% Luna) |

2.15×1022 (30% Luna) |

354,800 (90% Luna) |

-5.877 (20% Luna) |

Neptune's second known satellite (by order of distance), the irregular moon Nereid, has one of the most eccentric orbits of any satellite in the solar system.

From July to September 1989, Voyager 2 discovered six new Neptunian moons. Of these, the irregularly shaped Proteus is notable for being as large as a body of its density can be without being pulled into a spherical shape by its own gravity. Although the second most massive Neptunian moon, it is only one quarter of one percent of the mass of Triton. Neptune's innermost four moons, Naiad, Thalassa, Despina, and Galatea, orbit close enough to be within Neptune's rings. The next farthest out, Larissa was originally discovered in 1981 when it had occulted a star. This had been attributed to ring arcs, but when Voyager 2 observed Neptune in 1989, it was found to have been caused by the moon. Five new irregular moons discovered between 2002 and 2003 were announced in 2004.[25][26] As Neptune was the Roman god of the sea, the planet's moons have been named after lesser sea gods.

- For a timeline of discovery dates, see Timeline of discovery of Solar System planets and their natural satellites

Planetary rings

Faint azure coloured rings have been detected around the blue planet, but are much less substantial than those of Saturn. When these rings were discovered by a team led by Edward Guinan, it was thought that they might not be complete. However, this was disproved by Voyager 2.

These planetary rings have a peculiar "clumpy" structure,[27] the cause of which is not currently understood but which may be due to the gravitational interaction with small moons in orbit near them.[citation needed]

Evidence that the rings are incomplete first arose in the mid-1980s, when stellar occultation were found to occasionally show an extra "blink" just before or after the planet occulted the star. Images by Voyager 2 in 1989 settled the issue, when the ring system was found to contain several faint rings. The outermost ring, Adams, contains three prominent arcs now named Liberté, Egalité, and Fraternité (Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity). The existence of arcs is very difficult to understand because the laws of motion would predict that arcs spread out into a uniform ring over very short timescales. The gravitational effects of Galatea, a moon just inward from the ring, are now believed to confine the arcs.

Several other rings were detected by the Voyager cameras. In addition to the narrow Adams Ring 63,000 km from the centre of Neptune, the Leverrier Ring is at 53,000 km and the broader, fainter Galle Ring is at 42,000 km. A faint outward extension to the Leverrier Ring has been named Lassell; it is bounded at its outer edge by the Arago Ring at 57,000 km.[28]

New Earth-based observations announced in 2005 appeared to show that Neptune's rings are much more unstable than previously thought. Images taken from the W. M. Keck Observatory in 2002 and 2003 show considerable decay in the rings when compared to images by Voyager 2. In particular, it seems that the Liberté ring might disappear in as little as one century.[29]

Observation

Neptune is never visible with the naked eye, having a brightness between magnitudes +7.7 and +8.0, which can be outshined by Jupiter's Galilean moons, the dwarf planet Ceres and the asteroids 4 Vesta, 2 Pallas, 7 Iris, 3 Juno and 6 Hebe. A telescope or strong binoculars will resolve Neptune as a small blue disk, similar in appearance to Uranus; the blue colour comes from the methane in its atmosphere.[30] Its small apparent size has made it challenging to study visually; most telescopic data was fairly limited until the advent of Hubble Space Telescope and large ground-based telescopes with adaptive optics.

With an orbital period (sidereal period) of 164.88 Julian years, Neptune will soon return (for the first time since its discovery) to the same position in the sky where it was discovered in 1846. This will happen three different times, along with a fourth in which it will come very close to being at that position. These are April 11, 2009, when it will be in prograde motion; July 17, 2009, when it will be in retrograde motion; and February 7, 2010, when it will be in prograde motion. It will also come very close to being at the point of the 1846 discovery in late October through early-mid November 2010, when Neptune will switch from retrograde to direct motion on the exact degree of Neptune's discovery and will then be stationary along the ecliptic within 2 arc minutes at that point (closest on November 7, 2010). This will be the last time for approximately the next 165 years that Neptune will be at its point of discovery.

This is explained by the concept of retrogradation. Like all planets and asteroids in the Solar System beyond Earth, Neptune undergoes retrogradation at certain points during its synodic period. In addition to the start of retrogradation, other events within the synodic period include astronomical opposition, the return to prograde motion, and conjunction to the Sun.

Neptune will return to the same location on its orbit as at its discovery in August 2011.

Exploration

The closest approach of Voyager 2 to Neptune occurred on August 25, 1989. Since this was the last major planet the spacecraft could visit, it was decided to make a close flyby of the moon Triton, regardless of the consequences to the trajectory, similarly to what was done for Voyager 1's encounter with Saturn and its moon Titan.

The probe also discovered the Great Dark Spot, which has since disappeared, according to Hubble Space Telescope observations. Originally thought to be a large cloud itself, it was later postulated to be a hole in the visible cloud deck.

Neptune turned out to have the strongest winds of all the solar system's gas giants. In the outer regions of the solar system, where the Sun shines over 1000 times fainter than on Earth (still very bright with a magnitude of -21), the last of the four giants defied all expectations of the scientists.

One might expect that the farther one gets from the Sun, the less energy there would be to drive the winds around. The winds on Jupiter were already hundreds of kilometres per hour. Rather than seeing slower winds, the scientists found faster winds (over 1600 km/h) on more distant Neptune.

One suggested cause for this apparent anomaly is that if enough energy is produced, turbulence is created, which slows the winds down (like those of Jupiter). At Neptune however, there is so little solar energy that once winds are started they meet very little resistance, and are able to maintain extremely high velocities.[citation needed] Nonetheless, Neptune radiates more energy than it receives from the Sun,[31] and the internal energy source of these winds remains undetermined.

The images relayed back to Earth from Voyager 2 in 1989 became the basis of a PBS all-night program called Neptune All Night.[32]

See also

- Planets in astrology – Neptune

- Neptune in fiction

- Neptune Orbiter – Proposed space probe to Neptune to be launched after 2030.

- Neptune Trojans – Asteroids orbiting in Neptune's Lagrangian points.

- Neptune in music – One of the seven movements in Gustav Holst's orchestral suite, The Planets.

Notes

- ^ a b "Neptune". Solarviews. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ^ Yeomans, Donald K. (2006-07-13). "HORIZONS System". NASA JPL. Retrieved 2007-08-08. — At the site, go to the "web interface" then select "Ephemeris Type: ELEMENTS", "Target Body: Neptune Barycenter" and "Center: Sun".

- ^ Orbital elements refer to the barycenter of the Neptune system, and are the instantaneous osculating values at the precise J2000 epoch. Barycenter quantities are given because, in contrast to the planetary centre, they do not experience appreciable changes on a day-to-day basis from to the motion of the moons.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Williams, Dr. David R. (September 01, 2004). "Neptune Fact Sheet". NASA. Retrieved 2007-08-14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Seidelmann, P. Kenneth (2007). "Report of the IAU/IAGWorking Group on cartographic coordinates and rotational elements: 2006". Celestial Mech. Dyn. Astr. 90: 155–180. doi:10.1007/s10569-007-9072-y.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Refers to the level of 1 bar atmospheric pressure

- ^ NASA: Solar System Exploration: Planets: Neptune: Facts & Figures

- ^ "Neptune overview," Solar System Exploration, NASA.

- ^ Suomi, V. E.; Limaye, S. S.; Johnson, D. R. (1991). "High winds of Neptune - A possible mechanism". Science. 251: 929–932.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ T. R. Spilker and A. P. Ingersoll (November 9, 2004). Outstanding Science in the Neptune System From an Aerocaptured Vision Mission. 36th DPS Meeting, Session 14 Future Missions.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Alan (2001). Parallax:The Race to Measure the Cosmos. New York, New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-7133-4.

- ^ Littmann, Mark (2004). Planets Beyond: Discovering the Outer Solar System. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-4864-3602-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ A. Bouvard (1821), Tables astronomiques publiées par le Bureau des Longitudes de France, Paris, FR: Bachelier

- ^ Kollerstrom, Nick (2001). "Neptune's Discovery. The British Case for Co-Prediction". Unuiversity College London. Archived from the original on 2005-11-11. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ^ DIO 9.1 (June 1999); William Sheehan, Nicholas Kollerstrom, Craig B. Waff (December 2004). The Case of the Pilfered Planet - Did the British steal Neptune? Scientific American.

- ^ Hind, J. R. (1847). "Second report of proceedings in the Cambridge Observatory relating to the new Planet (Neptune)". Astronomische Nachrichten. 25: 309. Smithsonian/NASA Astrophysics Data System (ADS).

- ^ Using Eyepiece & Photographic Nebular Filters, Part 2 (October 1997). Hamilton Amateur Astronomers at amateurastronomy.org.

- ^ "Trio of Neptunes". Astrobiology Magazine. May 21, 2006. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ^ Crisp, D.; Hammel, H. B. (June 14, 1995). "Hubble Space Telescope Observations of Neptune". Hubble News Center. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Williams, Sam (2004). "Heat Sources Within the Giant Planets" (DOC). Retrieved 2007-10-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ McHugh, J. P., Computation of Gravity Waves near the Tropopause, AAS/Division for Planetary Sciences Meeting Abstracts, p. 53.07, September, 1999

- ^ McHugh, J. P. and Friedson, A. J., Neptune's Energy Crisis: Gravity Wave Heating of the Stratosphere of Neptune, Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, p.1078, September, 1996

- ^ Hammel, H.B.; et al. (1989). "Neptune's wind speeds obtained by tracking clouds in Voyager images". Science. 245: 1367–1369.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Neptune has a 'warm' south pole, astronomers find". Yahoo! News. September 19, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ^ Holman, Matthew J.; et al. (August 19, 2004). "Discovery of five irregular moons of Neptune". Nature. 430: 865–867.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Five new moons for planet Neptune". BBC News. August 18, 2004. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ^ "Missions to Neptune". The Planetary Society. 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature Ring and Ring Gap Nomenclature (December 8, 2004). USGS - Astrogeology Research Program.

- ^ "Neptune's rings are fading away". New Scientist. March 26, 2005. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ^ Moore, Patrick (2000). The Data Book of Astronomy. p. 207.

- ^ Beebe R. (1992). "The clouds and winds of Neptune". Planetary Report. 12: 18–21.

- ^ "Fascination with Distant Worlds". SETI Institute. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

References

- Adams, J. C. (November 13, 1846). "Explanation of the observed irregularities in the motion of Uranus, on the hypothesis of disturbance by a more distant planet". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 7: 149.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Airy, G. B. (November 13, 1846). "Account of some circumstances historically connected with the discovery of the planet exterior to Uranus". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 7: 121–144.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Challis, J., Rev. (November 13, 1846). "Account of observations at the Cambridge observatory for detecting the planet exterior to Uranus". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 7: 145–149.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Galle (November 13, 1846). "Account of the discovery of the planet of Le Verrier at Berlin". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 7: 153.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Dale P. Cruikshank (1995). Neptune and Triton. ISBN 0-8165-1525-5.

- Lunine J. I. (1993). "The Atmospheres of Uranus and Neptune". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 31: 217–263. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.31.090193.001245.

- Ellis D. Miner et Randii R. Wessen (2002). Neptune: The Planet, Rings, and Satellites. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 1-85233-216-6.

- Moore, Patrick (2000). The Data Book of Astronomy. CRC Press. ISBN 0-7503-0620-3.

- Smith, Bradford A. "Neptune." World Book Online Reference Center. 2004. World Book, Inc. (NASA.gov)

- Sheppard, Scott S. (June 2006). "A Thick Cloud of Neptune Trojans and Their Colors". Science. 313 (5786): 511–514. doi:10.1126/science.1127173.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- NASA's Neptune fact sheet

- Neptune Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- MPC's List Of Neptune Trojans

- Planets - Neptune A kid's guide to Neptune.

- Neptune and global warming

Future missions to Neptune