Joseph Smith

| Template:LDSInfobox/JS | ||||||

|

Joseph Smith, Jr. (December 23, 1805 – June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader who founded the Latter Day Saint movement, also known as Mormonism. Smith's followers declared him to be the first latter-day prophet, whose mission was to restore the original Christian church, said to have been lost soon after the death of Apostles because of an apostasy. This restoration included the establishment of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints and the publication of the Book of Mormon and other new scriptures. As a leader of large settlement communities, Smith also became a political and military leader in the American Midwest.

Although Smith's early Christian restorationist teachings were similar in many ways to other movements of his time, Smith was, and remains, a controversial and polarizing figure within Christianity because of his religious and social innovations, and his following, which has continued to grow to the present day.

Adherents to denominations originating from Joseph Smith's teachings currently number between thirteen and fourteen million followers. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is the largest denomination with approximately 13 million members.[1] The second largest is the Community of Christ, formerly the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, with about 250,000 members. Other groups have membership numbering from hundreds to the tens of thousands.[2]

Life

1805 to 1827

Joseph Smith, Jr. was born on December 23, 1805, in Sharon, Vermont to Joseph Smith, Sr. and Lucy Mack Smith. After his birth, the family moved to western New York, where they continued farming just outside the border of the town of Palmyra. This region was an area of intense revivalism and religious diversity during the Second Great Awakening. Although Smith had limited involvement with organized religion during his youth, he was religious, and influenced by folk religion.

Smith reported that, at the age of 14 (or thereabouts), he experienced a theophany, referred to by Latter Day Saints as the First Vision. Smith recorded several accounts of the vision later in life[3]. The version which is most well-known and read was published in 1838.

Smith reports he was concerned as to the correct church to join, and went to a grove of trees to pray. When he did, he recounts that he had a vision where he saw God the Father and his Son, Jesus Christ, appear to him as two separate, glorious, resurrected beings (in other accounts, they are described as heavenly beings). They told him that none of the churches established at the time were correct, and so he should join none of them. [4]

In earlier accounts of the vision, he states that he was also concerned with the welfare of his own soul and his sinfulness, and the heavenly beings told him that he was forgiven of his sins.[5]

Smith recounts that he reported his vision to a local minister, who believed it was "of the devil," because the minister believed "there were no such things as visions or revelations in these days; that all such things had ceased with the apostles, and there would never be any more of them." Smith said that he was soon the object of much persecution and reviling in his neighborhood, for maintaining that he had seen a vision.[6]

He also lived during what has been described as a "treasure hunting craze"[7], and prior to his ministry he was reluctantly employed to find buried treasure in various areas of western New York.[8]

In March 1826, Smith has been alledged to have been convicted of being a "disorderly person" and an "impostor" in a court in Bainbridge, New York.[9] However, the facts of the event are highly disputed.[10] In what remains of the court documents, some of the charges against Smith was described as a 'Glass Looker' for using his peep stone to locate buried treasure in exchange for fees. He met his wife Emma Hale Smith during a treasure-hunting expedition in Harmony, Pennsylvania (now Oakland), and the couple eloped in 1827.

Smith said that an 1823 visitation from a resurrected prophet named Moroni [11] led to his finding and unearthing (in 1827) a long-buried book, inscribed on metal leaves, which contained a record of God's dealings with the ancient Israelite inhabitants of the Americas. The record, along with other artifacts (including a sword, a compass-like device, a breastplate and what Smith referred to as the Urim and Thummim), was buried in a hill near his home. On September 22, 1827, Smith's record indicates that the angel allowed him (after years of waiting and preparation) to take the plates and other artifacts. Almost immediately thereafter Smith began having difficulties with his treasure-hunting colleagues who were trying to discover where the plates were hidden on the Smith farm.

1827 to 1830

Smith and his wife moved to Harmony, Pennsylvania, with the monetary and moral support of a wealthy Palmyra neighbor named Martin Harris. In Harmony, Smith reported to a few family members and colleagues including Harris that he had translated some of the Reformed Egyptian text from the Golden plates. According to Smith's history, he invited Harris to take a sample of the characters from the plates to a few well-known scholars including Charles Anthon. Harris returned to report that Anthon initially provided authentication to the translation of the Reformed Egyptian, but tore up his written statement upon hearing the story of how Joseph had obtained them.[12] Harris returned, and acted as Smith's scribe while Smith translated words using Urim and Thummim.[5] In June 1828, after completing the first 116 pages of the record, Smith allowed Harris to take the manuscript to Palmyra to show Harris' wife. Smith became despondent, however, when Harris reported that the manuscript had been lost at about the time Emma gave birth to a stillborn son, their first child. Smith ceased working on translating the record until about February 1829, when he began sporadically translating with Emma as scribe. Translation greatly intensified on April 7, 1829, when Oliver Cowdery, a local school teacher who had taken an interest in Smith's story began acting as scribe.

At the beginning of June 1829, Smith and Cowdery moved to Fayette, New York for the remainder of the translation, where the plates' title page indicated the book was to be entitled the Book of Mormon: An account written by the hand of Mormon, upon plates taken from the Plates of Nephi (Smith 1830b, title page). Translation was completed around July 1, 1829, and the Book of Mormon was published in Palmyra on March 26, 1830, with the financial assistance of Martin Harris.

By the time the Book of Mormon was published, Smith's record indicates that he had received additional revelations and had begun the work of organizing a new Christian church. Smith and Cowdery, after baptizing each other, proceeded to baptize several followers who called themselves the Church of Christ, a new church based on Smith's view of Christian theology which he discovered during his translation of the golden plates.

On April 6, 1830, this church was formally organized, and small branches were soon set up in Palmyra, Fayette, and Colesville, New York. There was strong local opposition to these branches, however, and Smith soon dictated a revelation (D & C 57:1-3) that the church would establish a "City of Zion" in Native American lands near Missouri. In preparation, Smith dispatched missionaries led by Oliver Cowdery to the area of this new "Zion". On their way, the missionaries converted a group of Disciples of Christ adherents in Kirtland, Ohio led by Sidney Rigdon. At the end of 1830, Smith dictated a revelation (D & C 37) that the three New York branches should gather in Ohio pending the results of Oliver Cowdery's mission to Missouri.

1831 to 1834

The church had more than doubled in size following the conversion of Sidney Rigdon, a former Campbellite minister in September 1830. Rigdon led several congregations of Restorationists in Ohio's Western Reserve area, and hundreds of his adherents followed him into Mormonism. Rigdon was soon called to be Smith's spokesman and quickly became one of the early leaders of the Movement.

To avoid further conflict encountered in New York and Pennsylvania, Smith moved with his family to Kirtland, Ohio joining with the converts that joined with Rigdon. The church's headquarters were soon established there and Smith urged the rest of the membership to gather there or to a second outpost of the church in Missouri. However, due to the controversy which followed him, he was not to escape persecution for long.

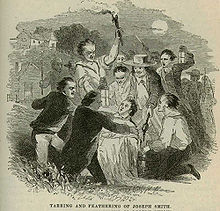

According to recorded accounts of the event, the mob broke down the front door, took Smith's oldest surviving adopted child from his arms (McKiernan 1971), dragged Smith from the room. [13] The mob beat, tarred and feathered, and attempted to poison Joseph.

1835 to 1838

Under Smith's leadership & direction, the church's first temple was constructed in Kirtland. The work of building the Kirtland Temple was begun in 1833, and was completed by 1836. Around the time of its completion, many extraordinary events were reported: appearances by Jesus, Moses, Elijah, Elias, and numerous angels, speaking and singing in tongues, prophesying, and other spiritual experiences.

However, the construction of the temple, in addition to other ventures of Smith's, left him and the Church in deep debt.[14] To raise money, Smith planned a banking institution, which was called the Kirtland Safety Society. The State of Ohio denied Smith a charter to legally operate a bank causing Smith to rename the company under the advice of non-Mormon legal counsel as 'The Kirkland AntiBanking Safety Society' and he continued to operate the bank and print notes. The bank collapsed after 21 days of operation in January.[15] During this time, Smith and his associates were accused of illegal and unethical actions.[16] In the wake of this bank failure, many Mormons, including prominent leaders, became disaffected with Smith, who had backed the venture and is alleged to have prophesied it would become the largest bank on earth. [17]

Eventually, lawsuits and indictments against Smith and his banking partners became so severe that, on January 12, 1838, Smith and Rigdon left Kirtland by dark of night for the Far West settlement in Caldwell County, Missouri. At the time, there were at least $6,100 in civil suits outstanding against him in Chardon, Ohio courts, and an arrest warrant had been issued for Smith on a charge of bank fraud.[18] Those who continued to support Smith left Kirtland for Missouri shortly thereafter.

Independence, Missouri was identified as "the center place"[19] and the spot for building a temple. Smith first visited Independence in the summer of 1831, and a site was dedicated for the construction of the temple. Soon afterward, Mormon converts—most of them from the New England area—began immigrating in large numbers to Independence and the surrounding area.

The Missouri period was marked by many instances of violent conflict and legal difficulties for Smith and his followers. The Mormons and non-Mormons in Missouri were, in general, fundamentally very different people. Local leaders and residents saw the Latter Day Saint community as a threat to their property and their political control due to the Mormon practice of voting 'in block'. The tension was further fueled by the Mormon belief that Jackson County, Missouri, and the surrounding lands would become a "promised land" to the Mormons as they purchased property and built settlements. The 'Latter Day Saints' began migrating to Missouri after Smith stated that Missouri would be the future center of the New Jerusalem. One main group resided in the Kirtland area, while others moved to the Missouri settlements, resulting in two main centers for approximately seven years. After Mormon leadership left Kirtland in 1838, the Saints from Kirtland followed them to Missouri increasing the church's numbers, which confirmed the fears of the local leaders and residents that the Mormons would dominate Missouri politics.

Later in 1838, many non-Mormon residents of Missouri, and the LDS settlers engaged in an ongoing conflict often referred to as the Mormon War. After several skirmishes, the Battle of Crooked River (which involved Missouri state militia troops and a group of Latter Day Saints) occurred.[20] Many exaggerated reports of this battle (some claimed that half of the militia's men had been lost, when in fact they had suffered only one casualty), as well as affidavits by ex-Mormons that Mormons were planning to burn both Liberty and Richmond, Missouri, made their way to Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs. Smith is reported to have stated.[21]:

I will be to this generation a second Muhammed, whose motto in treating for peace was "the Alcoran (Koran) or the sword." So shall it eventually be with us, "Joseph Smith or the sword!"

Boggs issued an executive order in response on 27 October 1838, known as the "Extermination Order". It stated that the Mormon community had "made war upon the people of this State" and that "the Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the State if necessary for the public peace".[22][23] The Extermination Order was not officially rescinded until 1976 by Missouri Governor Christopher S. Bond.

Soon afterward, the 2,500 troops from the state militia converged on the Mormon headquarters at Far West. They raided Far West, ransacked their homes, raped their women and killed several.[citation needed] Smith and several other Church leaders were brought into the Missouri Militia by Colonel George M. Hinkle under false pretenses. Hinkle then handed the prisoners over to General Lucas. They were held at Liberty Jail, and spent several months in captivity. They were later transferred to a jail in Columbia, Missouri.

The legality of Boggs' "Extermination Order" was debated in the legislature, but its objectives were achieved. Most of the Mormon community in Missouri had either immediately left or been forced out by the spring of 1839.

1838 to 1842

After escaping Missouri in 1839, Smith and his followers regrouped. They established a new headquarters in a town on the banks of the Mississippi River, called Commerce, in Hancock County, Illinois, which they renamed Nauvoo. They were granted a charter by the state of Illinois, and Nauvoo was quickly built up by the faithful, including many new arrivals. The Nauvoo city charter authorized independent municipal courts, the foundation of a university and the establishment of a militia unit known as the "Nauvoo Legion." These and other institutions gave the 'Latter Day Saints' a considerable degree of autonomy.

In October 1839, Smith and others left for Washington, D.C. to meet with Martin Van Buren, then the President of the United States. Smith and his delegation sought redress for the persecution and loss of property suffered by the Saints in Missouri. It was reported by Smith that Van Buren told Smith, "Your cause is just, but I can do nothing for you. If I take up for you I shall lose the vote of Missouri."[24]

Construction of a new temple in Nauvoo began in the autumn of 1840. It was significantly larger and more grandiose than the one left behind in Kirtland, as it was intended for different functions (member endowments and baptisms) than the first temple (which could be used for large gatherings). The cornerstones were laid during a conference on April 6, 1841. Although Smith was instrumental in its completion, it was not finished for more than five years - after Smith's death. It was dedicated on May 1, 1846, well after Nauvoo citizens had begun abandoning the city for points west (the first significant exodus occurred in February 1846). Approximately four months afterward, Nauvoo had been abandoned by the majority of its citizens under threats of mob action.

1842 to 1844

On March 15, 1842, Smith was initiated as an Entered Apprentice Mason at the Nauvoo Lodge. The next day, he was raised to the degree of Master Mason; the usual month-long wait between degrees was waived by the Illinois Lodge Grandmaster, Abraham Jonas.[25][26][27][28][29][30] Some commentators have noted similarities between portions of temple ordinance of the endowment and the Royal Arch Degree of Freemasonry.[31] [32][33][34] (See Freemasonry and the Latter Day Saint movement.)

In Nauvoo, Smith taught doctrines he believed were practiced in the early Christian church such as Baptism for the dead. He also introduced other teachings and ordinances such as the Endowment[35], and "the principle" of plural marriage neither of which are found in mainstream Christianity.[36]

In February, 1844, Smith announced his candidacy for President of the United States, with Sidney Rigdon as his vice-presidential running mate. He also theorized a quasi-republican political system which he termed Theodemocracy and organized the Council of Fifty based upon its principles.

Death

A few disaffected Mormons in Nauvoo joined together to publish a newspaper, the Nauvoo Expositor. Its first and only issue was published 7 June 1844. The paper was highly antagonistic toward Smith, expounding many beliefs critical of him, and outlining several grievances against him. The bulk of the Expositor's single issue was devoted to criticism of Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint movement and the mayor of Nauvoo, and inflamed many of Nauvoo's citizens. The city council, headed by Joseph Smith as mayor, responded by passing an ordinance declaring the newspaper a public nuisance designed to promote violence against Smith and his followers.[37] Under the council's new ordinance, Nauvoo's mayor, Smith, in conjunction with the city council, ordered the city marshal to destroy the paper and the press on June 10, 1844.[38]

This action was seen by many non-Mormons as illegal and Smith was accused of violating the freedom of the press. Violent threats were made against Smith and the Mormon community. Charges were brought against Smith and he submitted to incarceration in Carthage, the Hancock County seat. Smith's brother, Hyrum, and eight of his associates including John Taylor and Willard Richards, accompanied him to the jail.[39] The Governor of the state, Thomas Ford, had promised protection and a fair trial.[40] All of Smith's associates left the jail, except his brother Hyrum, Richards and Taylor. Those in jail were not held in the 1st floor jail cell because the jailer felt that that was unsafe; instead they were held in the jailer's room on the 2nd floor.

Shortly after 5:00 p.m. on June 27, 1844, a mob of about 200 men stormed the jail, and went to where Smith and his associates were imprisoned. Although they attempted to hold the door shut against the mob, the mob opened fire through the still-closed door, shooting Hyrum Smith in the face. As the mob burst through the doorway, Joseph Smith (who had earlier been given a six-shooter by a visitor) managed to fire three shots at the mob.[41] His brother Hyrum Smith died immediately from the shot in the face. Taylor was shot several times, but survived. One of the bullets hit his pocket watch, saving his life. Richards was unharmed. Smith ran to the open window, where he was shot multiple times simultaneously (both from within the room and from the outside), and fell from the window, dead. Upon falling to the ground, he was shot several more times. Mormons view his death as martyrdom.

Smith and his brother were interred below the Smith Homestead in Nauvoo, and later excavations ordered by his grandson Frederick M. Smith rediscovered the bodies, and along with his wife's, were reinterred in a location thought to be more safe from Mississippi flooding.[citation needed]

Marriage and family

Smith met Emma Hale in 1825 when he boarded with the Hales while he was employed in a company hoping to unearth buried treasure. Although the company was unsuccessful, Smith returned to Harmony several times seeking Emma's hand. Isaac Hale, Emma's father, refused to allow the marriage so the couple eloped across the state line to South Bainbridge, New York, present day Afton, New York, and were married on 18 January 1827, by the Village of Afton, New York Justice of the Peace. The couple initially moved to the home of Smith's parents on the edge of Manchester Township near Palmyra.

During the early portion of their marriage, Joseph and Emma Smith had the following children:

- June 15, 1828, Alvin, who lived only a few hours.

- April 30, 1831, twins, Thaddeus and Louisa, who died hours after their premature birth.

- April 30, 1831, twins Joseph and Julia. These were the children of Julia Clapp Murdock and John Murdock. Murdock, upon his wife's death in childbirth, gave the infants to the Smiths (who had just lost their own twins) to adopt.

The couple later had four additional sons:

- November 6, 1832, Joseph Smith III

- June 29, 1836, Frederick Granger Williams Smith

- June 2, 1838, Alexander Hale Smith.

- November 17, 1844, David Hyrum Smith, born after Joseph's death.

Plural marriages

Smith was reportedly married to other women along with Emma. In some of these cases evidence exists that he was sealed to other women. Many documented cases were witnessed. Additionally, sealings took place years after his death by proxy in the 1850s in Utah. Most of the "plural wives" left letters and statements that stated their marriages were consummated. Although Smith fathered several children with Emma, no additional offspring from any of the women making a "plural wife" claim has ever been proven. [42] In official church publications, Smith publicly denied such doctrines existed.[43] During Smith's lifetime, his wife Emma reportedly "vacillated between acceptance and rejection" of the practice,[44] with Emma even attending the marriage of Smith to at least one of his plural wives.[45] However, Emma died denying that her husband ever had any other wives, as did Smith's eldest son Joseph. Emma Smith's deathbed testimony stated "no such thing as polygamy, or spiritual wifery, was taught, publicly or privately, before my husband's death, that I have now, or ever had any knowledge of...He had no other wife but me; nor did he to my knowledge ever have".[46] However, one modern commentator has stated that due to Emma's opposition to plural marriage, Smith "moved ahead surreptitiously", resulting in Emma's being unaware of the existence of many of Smith's plural wives.[47] Some degree of Emma's opposition may have been directed at clearing up the aftermath of an incident in which:

John C. Bennett, mayor of Nauvoo and adviser to Joseph Smith, ...twisted the teaching [of plural marriage] to his own advantage. Capitalizing on rumors and lack of understanding among general Church membership, he taught a doctrine of "spiritual wifery." He and associates sought to have illicit sexual relationships with women by telling them that they were married "spiritually," even if they had never been married formally, and that the Prophet approved the arrangement. The Bennett scandal resulted in his excommunication and the disaffection of several others.[48]

Claims that Smith neither taught nor practiced polygamy were challenged by the official publication by the LDS Church in Utah of the Doctrine and Covenants Section 132 in 1852. This document, stating to be a revelation recorded on July 12, 1843 in which Jesus Christ[49] is believed to have revealed through Smith that "a new and an everlasting covenant" of plural marriage is given, contains numerous Biblical references to and justifications of polygamy, as well as the demand that Smith's wife, Emma, accept all of Smith's plural wives, and warns of damnation if the new covenant is not observed.[50] In his personal records, Smith nowhere explicitly mentions plural marriage or the existence of other wives; however, his scribe Willard Richards is believed to have recorded Smith's plural marriages in Smith's journal in code.[51] He does write a sincere apology to his wife Emma, but the page explaining what he had done is torn out.[52] Some sects of the Latter Day Saint movement believe he was apologizing for an extramarital affair brought to light by Oliver Cowdery shortly before Cowdery's excommunication.[citation needed] It was only after his death that some, including William Marks and Brigham Young, came forward and publicly claimed that Smith taught and practiced plural marriage.

At least nine of Joseph Smith's several wives were practicing polyandry (the practice of a woman having more than one husband at one time).[53][54] Most of these polyandrous marriages were with the first husband's consent, while others were done behind the first husband's back.[55] Smith used warnings of eternal damnation and promises of eternal rewards to secure consent to his proposals.[56] No certain evidence exists as to whether Joseph had sexual relations with any of these polyandrous wives.[57]

Major teachings

During his adult life — from the time he began dictating the Book of Mormon in 1827 until his death in 1844 — Smith introduced a large number of religious teachings. Although a number of his teachings are similar to doctrines circulating during his lifetime, several are unique to Smith.

Nearly all Smith's teachings had some root in the King James Version of the Bible, or his interpretation or elaboration of it. However, he believed in other scripture, and that in some instances, the Bible was translated incorrectly.[58] Thus, he "restored" temples, orders of priesthood, and other elements of the Bible that he felt had been wrongly abandoned by mainstream Christianity as part of a Great Apostasy. Much of this "restoration" is presented in the Doctrine and Covenants, which is described as modern scripture.

In many cases, Smith's doctrines or interpretations of the Bible, as well as his own revelations, placed him at odds with mainstream Christianity. For example, it has been interpreted by some Latter Day Saints that Smith rejected mainstream Christianity's long-standing formulation of the Trinity as recorded in the 4th Century Nicene Creed.

In what has come to be known as the Wentworth letter, Joseph Smith, Jr. wrote and sent a list of the basic beliefs of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints to "Long" John Wentworth, editor of the Chicago Democrat. These articles of faith were subsequently published in Times and Seasons, a newspaper published by the church (see Articles of Faith (Latter Day Saints)).

Legacy

Immediate reaction

Smith's death created a crisis for the Latter Day Saints. Their charismatic founder was dead and their hierarchy was scattered on missionary efforts and in support of Smith's presidential campaign. Brigham Young recorded in his journal his initial concern after Smith's murder: "The first thing which I thought of was, whether Joseph had taken the keys of the kingdom with him from the earth." Without the keys of the kingdom, that is, the appropriate Priesthood authority, Young recognized the possibility that, according to the church's doctrine and Smith's own teachings, the church lacked a divinely-sanctioned leader.

Because of ongoing tensions, the state legislature revoked Nauvoo's city charter and it was disincorporated. All protection, public services, self-government and other public benefits were revoked. Those who lived in the former City of Nauvoo referred to it as the City of Joseph—He being its founder—after this time, until the city was again granted a charter. Without official defenses, city residents continued to be persecuted by opponents, leading Young to consider other areas for settlement, including Texas, California, Iowa, and the Great Basin region.

Succession

Smith left ambiguous or contradictory succession instructions that led to arguments and disagreements among the church's members and leadership, several of whom claimed rights to leadership.

An August 8, 1844 conference which established Young's leadership is the source of an oft-repeated legend. Multiple journal and eyewitness accounts from those who followed Young state that when Young spoke regarding the claims of succession by the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, he appeared to look or sound like the late Smith. Although many of these accounts were written years after the event, there were contemporary records. Historian D. Michael Quinn wrote:

The Times and Seasons reported that just before the sustaining vote at the afternoon session of the August meeting, "every Saint could see that Elijah's mantle had truly fallen upon the 'Twelve.'" Although the church newspaper did not refer to Young specifically for the "mantle" experience, on 15 November 1844 Henry and Catharine Brooke wrote from Nauvoo that Young "favours Br Joseph, both in person, manner of speaking more than any person ever you saw, looks like another." Five days later Arza Hinckley referred to "Brigham Young on [w]hom the mantle of the prophet Joseph has fallen."[59]

Most Latter Day Saints followed Young, but some aligned with other various people claiming to be Smith's successor. Some waited for Smith's son, Joseph Smith III, to assume leadership of the church despite his young age at the death of his father. The church had published a revelation in 1841 stating "I say unto my servant Joseph, In thee, and in thy seed, shall the kindred of the earth be blessed",[60] and this was widely interpreted as endorsing the concept of Lineal Succession. Documentary evidence indicates also that Smith set apart his son as his successor at various private meetings and public gatherings, including Liberty[61] and Nauvoo.[62] Indeed, Brigham Young assured the bulk of Smith's followers as late as 1860 that young Joseph would eventually take his father's place.[63] That year, the younger Smith became leader of what was to later be incorporated as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now called the Community of Christ church) in the Midwest, made up of scattered church members not having journeyed west with Young, including Smith's widow Emma and two of Joseph III's brothers.

In addition, Smith's Vice Presidential running mate Sidney Rigdon formed the Church of Jesus Christ, headquartered in Greensburg, Pennsylvania with a few more congregations scattered throughout the area.

Many of these smaller groups were spread throughout the midwestern United States, especially in Independence, Missouri, and several remain viable as religious groups. Issues relating to the succession crisis are still the subject of discussion and debate.

In the modern media

- In film, Joseph Smith has been portrayed by several actors including Vincent Price (Brigham Young), Dean Cain (September Dawn), Jonathan Scarfe (The Work and The Glory), Nathan Mitchell (Joseph Smith: Prophet of the Restoration) and Richard Moll (Brigham).

- Smith was the subject of the cover of Newsweek Magazine, dated October 17, 2005. The cover was a reproduction of a stained-glass window portraying the First Vision. Many opinions on Joseph Smith were quoted, ranging from LDS Church President Gordon B. Hinckley to Mark Scherer, official historian of the Community of Christ.

- On TV, Joseph Smith's life as a prophet was satirized in the South Park episode All About Mormons in 2003. Joseph Smith was also featured as member of the Super Best Friends, a superhero-type group of various major religious leaders and gods, on an earlier episode.

- A PBS documentary called "The Mormons" aired April 30 and May 1, 2007. Additional airings may be available.

Notes

- ^ "LDS Church says membership now 13 million worldwide", Salt Lake Tribune, June 25, 2007. See LDS Membership Indicators regarding membership counts compared to attendance.

- ^ Steven L. Shields, Divergent Paths of the Restoration: A History of the Latter Day Saint Movement, Los Angeles: 1990

- ^ Bushman, pg. 39-40

- ^ Joseph Smith - History 1:15-20

- ^ Bushman, pg. 39

- ^ Joseph Smith - History 1:20-25

- ^ Bennett 1893. See also Quinn 1998, pp. 25–26 (describing widespread treasure-seeking in early 19th century New England).

- ^ Dan Vogel, 2002, Early Mormon Documents Volume 4, Signature Books, 252-253.

- ^ Morgan, D: "Dale Morgan on Early Mormonism: Correspondence and a New History", Appendix A. Signature Books, 1986

- ^ Richard L. Bushman, Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Mormonism (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1984), 70

- ^ Joseph Smith - History 1:50

- ^ Joseph Smith History

- ^ The historian Fawn M. Brodie (No Man Knows, 119) speculated that one of John Johnson's sons, Eli, meant to punish Joseph by having him castrated for an intimacy with his sister, Nancy Marinda Johnson, but author Bushman states that hypothesis failed. Bushman feels a more probable motivation is recorded by Symonds Ryder, a participant in the event, who felt Smith was plotting to take property from members of the community and a company of citizens violently warned Smith that they would not accept those actions.

- ^ Bushman, pg. 329. By 1837, Smith had run up a debt of over $100,000

- ^ Technically, the bank did not close its doors until November, but by January 23, payment had stopped. Bushman, pg. 330.

- ^ Chardon, Ohio court records, Vol U, p. 362, Brodie 1971, p. 198

- ^ Bushman, pg. 331

- ^ Brodie 1971, p. 207

- ^ The Doctrine and Covenants, Covenant 57:3

- ^ There is some debate as to whether the Mormons knew their opponents were government officials.

- ^ Brodie, Fawn M. (1971). No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith (Second Edition ed.). New York, NY: Alfred A Knoff. p. 230.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ "Extermination Order". LDS FAQ. Retrieved August 22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Boggs, Extermination Order

- ^ Smith, Joseph Fielding (1946–1949). "Church History and Modern Revelation". 4. Deseret: 167–173.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ http://www.masonicinfo.com/mormons.htm

- ^ http://www.signaturebooks.com/excerpts/anointed2.htm

- ^ http://www.fairlds.org/FAIR_Conferences/2005_Latter-day_Saints_and_Freemasonry.html

- ^ http://www.ftfacts.com/morm.htm

- ^ http://www.mastermason.com/masonicmoroni/Images1.htm

- ^ http://www.experiencefestival.com/a/Joseph_Smith_Jr_-_Biography/id/1539122

- ^ Mormon America: The Power and the Promise, Richard Ostling, Joan K. Ostling. Harper Collins, 1999, p. 188 "Smith was an active Mason when he introduced the endowment ordinance two years before his death, and many scholars have noted the strong resemblance between the Mormon ordinance and Masonic ritual."

- ^ Mormon America: The Power and the Promise, Richard Ostling, Joan K. Ostling. Harper Collins, 1999, p. 194-5, "Early Mormons were fairly open in recognizing the connection between the endowment ritual and Masonry. Apostle and First Counselor Heber C. Kimball wrote that Smith believed in the 'similarity of preast Hood in Masonary.' Other early church leaders taught that the Masonic ceremony was a corrupted form of temple rituals that had descended directly from the biblical Solomon and were restored to the true, pristine form by the inspired Joseph Smith. ... Joseph Smith became a Mason in March 1842, advancing all the way to Master Mason the next day. This was highly unusual since the normal minimum wait between each of the three degrees is thirty days. In the weeks that followed he observed Masonic ritual degree advancements thirteen times before introducing the endowment ceremony on May 4 and 5, 1842.

The essentially British version of Masonry as probably practiced in Nauvoo included such elements as ritual anointing of body parts; a ... drama as a metaphor for a spiritual journey; bestowal of a secret name (as a password into eternity); special garments (in Mormonism, sacred undergarments) when stepping through a veil in glorified ascent to a Celestial Lodge; secret handshakes and tokens; promises to fulfill moral obligations; penalty oaths to protect secrecy; progression through three degrees toward perfection; the use of special temple robes and aprons; and the word exalted to signify becoming kings in connection with the Royal Arch degree. Masons regard the lodge as a temple. All these elements have strong parallels in Smith's endowment ceremony. In addition, Masonic symbols that have been adapted by Mormons on everything from temples to gravestones to logos include: the beehive, the square and compass, two triangles forming a six-pointed star, the all-seeing eye, sun, moon, and stars, and ritualistic hand grips." - ^ The Mormon Murders, Steven Naifeh, Gregory White Smith, St Martin's Press, 1988. p. 78, "But like many Mormon boys with doubts, Mark was already caught up in the intriguing, Masonic-like initiation rites of the Mormon priesthood, the secret passwords, the secret handshakes, the special garments."

- ^ Heber C. Kimball: Mormon Patriarch and Pioneer, Stanley B. Kimball, p. 85: "Heber thought he saw similarities between Masonic and Mormon ritual." "Heber seems to have felt that both Mormonism and Masonry derived separately from ancient ceremonies connected with Solomon's temple."

- ^ Smith did not teach this in public before his death, but did teach it to the Quorum of the Twelve and the Council of Fifty, who taught it once the temple was completed

- ^ Some Mormons dispute, as a matter of faith, the historicity of Smith's polygamy, since during Smith's lifetime he publicly denied having ever taught or practiced polygamy and condemned the practice. Indeed, his widow and sons throughout their lifetimes were vehement that Smith had no association with the practice, and no offspring clearly identifiable as Smith's were produced from the many women claiming after his death to have been his plural wives. Nonetheless, there is a clear historical consensus and sound documentation evidencing the fact that Smith did indeed practice polygamy, perhaps with as many as 50 wives. The exact number is difficult to determine because of Smith's secrecy, differing accounts and some statements made by witnesses many years after the fact. Smith took his first plural wife, Fanny Alger, while in Kirkland and then took an additional 30 to 40 wives in Nauvoo. Emma Smith was bitterly opposed to this practice.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "The Destruction of the "Nauvoo Expositor"—Proceedings of the Nauvoo City Council and Mayor".

- ^ The six other associates that accompanied them were: John P. Greene, Stephen Markham, Dan Jones, John S. Fullmer, Dr. Southwick, and Lorenzo D. Wasson[2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ Decision of Judge Philips in the Temple Lot Case (Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints v. Church of Christ at Independence, Missouri) pages 42-43; Federal Reporter, 60:937-959.

- ^ Times and Seasons, Volume 5, p. 423, see also Volume 5, page 474; Volume 5, pp 490-491

- ^ Bushman, Richard Lyman (2006). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York, NY: Alfred A Knoff. p. 490.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Bushman, Richard Lyman (2006). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York, NY: Alfred A Knoff. p. 494.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ The History of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, Volume 3, pp. 355-356, Independence, Mo, Herald House Publishing, 1967- , c1896-; ISBN 0830900756

- ^ Bushman, Richard Lyman (2006). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York, NY: Alfred A Knoff. p. 494.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Encyclopedia of Mormonism, "Plural Marriage"

- ^ The Doctrine and Covenants, 132:24.

- ^ Joseph Smith's 12 July 1843 polygamy revelation on plural marriage with the demand that Emma Smith, the first wife, accept all of Joseph Smith's plural wives; The Doctrine and Covenants, 132:1–4, 19, 20, 24, 34, 35, 38, 39, 52, 60–62.

- ^ Bushman, Richard Lyman (2006). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York, NY: Alfred A Knopf. p. 491.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Bushman, Richard Lyman (2006). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York, NY: Alfred A Knopf.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Bushman, Richard Lyman (2006). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York, NY: Alfred A Knoff. p. 439.

All told, ten of Joseph's plural wives were married to other men....All of them went on living with their first husbands after marrying the Prophet.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Template:Harvard reference"Eighteen of Joseph's wives…were single when he married them and had never been married previously. Another four…were widows. One…was the widow of his younger brother, Don Carlos, making this a strict Levirate marriage. However, the remaining eleven women…were married to their husbands and cohabiting with them when Smith married them." p. 15. "Of Smith's first twelve wives, nine were polyandrous." p. 15.

- ^ Template:Harvard referenceCompton postulates that "Smith regarded marriage performed without Mormon priesthood authority as invalid (see D&C 132:7)…Thus all couples in Nauvoo who accepted Mormonism were suddenly unmarried." p. 17.

- ^ Template:Harvard reference "Smith was always persistent in his marriage proposals, and rejections usually moved him to further effort." "Smith usually expressed his polygamous proposals in terms of prophetic commandments." p. 80. When Smith ordered Heber Chase Kimball "to surrender his wife, his beloved Vilate, and give her to Joseph in marriage," Heber consented, but the marriage did not occur. Instead, Smith required Heber to marry Sarah Peake Noon, and "commanded Heber to keep the plural marriage secret even from Vilate." "Heber was told by Joseph that if he did not do this he would lose his apostleship and be damned." p. 495-6. Ultimately, Heber Chase Kimball would marry 45 women. p. 127. Pursuing his proposal to Helen Mar Kimball, then fourteen years old, Smith said to her, "If you will take this step, it will ensure your eternal salvation & exaltation and that of your father's household & all of your kindred." "This promise was so great," she said, "that I willingly gave myself to purchase so glorious a reward."

- ^ Bushman, Richard Lyman (2006). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York, NY: Alfred A Knoff. p. 439.

There is no certain evidence that Joseph had sexual relations with any of the wives who were married to other men. They married because Joseph's kingdom grew with the size of his family, and those bonded to that family would be exalted with him.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ See Wentworth letter.

- ^ Quinn, D. Michael (1994). The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. pp. p. 166. ISBN 1-56085-056-6.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Covenant 107:18c

- ^ Joseph Smith III; Joseph Smith III and the Restoration; Herald House; 1952, p. 13

- ^ Autumn Leaves, Vol 1; p. 202

- ^ Brigham Young: Journal of Discourses; Vol 8; P 69

References

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Brodie, Fawn M. (1971). No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith (2nd edition ed.). New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-679-73054-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Bushman, Richard Lyman (2005). Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York: Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4270-4.

- Bushman, Richard Lyman (2007). On the Road with Joseph Smith: An Author's Diary. Salt Lake City,UT: Greg Kofford Books. ISBN 1-58958-102-4.

- Bidamon, Emma Smith (March 27, 1876), letter to Emma S. Pilgrim, published in Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference, republished in Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Norwich, Vermont (March 15, 1816), A Record of Strangers Who are Warned Out of Town, 1813–1818 (Norwich Clerk's Office), p. 53, published in Template:Harvard reference, page 666.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Smith, Joseph, Jr. (1832) History of the Life of Joseph Smith, in Joseph Smith Letterbook 1, pp. 1–6, Joseph Smith Collection, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City, published in Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Smith, Joseph, Jr. et al. (1838–1842) History of the Church Ms., vol. A–1, pp. 1–10, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City, published in Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

In addition, Smith is also the main subject of virtually all works dealing with the early Latter Day Saint movement.

See also

- Smith Political Family

- History of the Latter Day Saint movement

- Controversies regarding Mormonism

- Joseph Smith: Prophet of the Restoration (film)

- Joseph Smith, Jr. and Polygamy

- Lectures on Faith

- List of assassinated American politicians

External links

- Works by Joseph Smith, Jr. at Project Gutenberg

- "Who was Joseph Smith?" - At Mormon.org

- JosephSmith.net - The official web site on Joseph Smith by the LDS Church.

- JosephSmith.com

- Joseph Smith - collection of articles about Joseph Smith from LightPlanet.com

- Joseph Smith Daguerreotype - The only known photograph of Joseph Smith

- Joseph Smith, Jr. - The Prophet - a Mormon film about Joseph Smith

- The Restoration (Google Video) - a Mormon film about Joseph Smith

- LibraryThing author profile

- Joseph Smith Chronology Chart

| Leader of the Church of Christ, later called the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints | |

|---|---|

| Joseph Smith, Jr. (1830–1844) Founding president | |

| Successor (as claimed by various Latter Day Saint movement denominations) | |

| The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Quorum of the Twelve (led by Brigham Young) 1844–1847 | |

| Community of Christ ("RLDS Church"): Joseph Smith III 1860–1914 | |

| Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Strangite): James Strang 1844–1856 | |

| The Church of Jesus Christ: William Bickerton (follower of Sidney Rigdon) 1862 | |

- 1805 births

- 1844 deaths

- American Latter Day Saints

- American murder victims

- American religious leaders

- Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Assassinated American politicians

- Book of Mormon witnesses

- Charismatic religious leaders

- Deaths by firearm in the United States

- Editors of Latter Day Saint publications

- Founders of religions

- History of the Latter Day Saint movement

- Joseph Smith, Jr.

- Latter Day Saint missionaries

- Latter Day Saint politicians

- Members of the Council of Fifty of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Mormon martyrs

- Presidents of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Prophet–Presidents of the Community of Christ

- Prophets

- Smith family

- United States presidential candidates

- Victims of religiously motivated violence in the United States