Underground Railroad

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2007) |

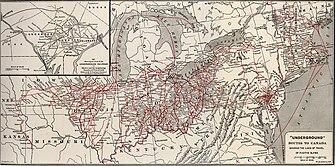

The Underground Railroad was an informal network of secret routes and safe houses that 19th century African slaves in the United States used to escape to free states (or as far north as Canada) with the aid of abolitionists.[1] The term is also applied to the abolitionists who aided the fugitives.[2] Other routes led to Mexico or overseas.[3] At its height between 1810 and 1850,[4] one report estimated up to 100,000 people escaped enslavement via the Underground Railroad,[2] though census figures only account for 6,000.[5] The Underground Railroad has captured public imagination as a symbol of freedom, and it figures prominently in African-American history.

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Structure

The escape network was "underground" in the sense of underground resistance but was seldom literally subterranean. The network was known as a "railroad" by way of the use of rail terminology in the code. The Underground Railroad consisted of clandestine routes, transportation, meeting points, safe houses and other havens, and assistance maintained by abolitionist sympathizers. These individuals were organized into small, independent groups who, for the purpose of maintaining secrecy, knew of connecting "stations" along the route but few details of their immediate area. Many individual links were via family relation. Escaped slaves would pass from one way station to the next, steadily making their way north. The diverse "conductors" on the railroad included free-born blacks, white abolitionists, former slaves (either escaped or manumitted), and Native Americans. Churches and religious denominations played key roles, especially the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), Congregationalists, Wesleyans, and Reformed Presbyterians as well as breakaway sects of mainstream denominations such as branches of the Methodist church and American Baptists.

Route

Many people associated with the Underground Railroad only knew their part of the operation and not of the whole scheme. Though this may seem like a weak route for the slaves to gain their freedom, hundreds of slaves obtained freedom to the North every year.

The resting spots where the runaways could sleep and eat were given the code names “stations” and “depots” which were held by “station masters”. There were also those known as “stockholders” who gave money or supplies for assistance. There were the “conductors” who ultimately moved the runaways from station to station. The “conductor” would sometimes act as if he or she were a slave and enter a plantation. Once a part of a plantation the "conductor" would direct the fugitives to the North. During the night the slaves would move, traveling on about 10–20 miles (15–30 km) per night. They would stop at the so-called “stations” or "depots" during the day and rest. While resting at one station, a message was sent to the next station to let the station master know the runaways were on their way. Sometimes boats or trains would be used for transportation. Money was donated by many people to help buy tickets and even clothing for the fugitives so they would remain unnoticeable. Soon after the railroad had freed 300 slaves, some of the freed slaves made a store for the railroad.

Some people — most of them, naturally, pro-slavery Southerners — were upset by this whole process. Resulting from many efforts to fix this ostensible problem, a law was passed that allowed slave owners to hire people to catch their runaways and arrest them. The fugitive slave laws became a problem because many legally freed slaves were being arrested as well as the fugitives. This then encouraged more people of the North to become a part of the Underground Railroad. Oftentimes, "bounty hunters" would abduct free blacks, and sell them into slavery.

Traveling conditions

Although the fugitives sometimes traveled on real railways, the primary means of transportation were on foot or by wagon.

Ismary Istroyer tells her story, "It were so hard to travel, all by myself. It took 89 long tiring days. I traveled through 23 swamps, and had nothing to eat, but grass, leaves, and the rare food I would get at a stationers house."

The routes taken were indirect to throw off pursuers. Most escapes were by individuals or small groups; occasionally, such as with the Pearl Rescue, there were mass escapes. The majority of the escapees are believed to have been male field workers younger than 40 years old. The journey was often too arduous and treacherous for women and children to complete successfully. It was relatively common, however, for fugitive bondsmen who had escaped via the Railroad and established livelihoods as free men to purchase their wives, children, and other family members out of slavery in series, and then arrange to be reunited with them. In this manner, the number of former slaves who owed their freedom at least in part to the courage and determination of those who operated the Underground Railroad was greater than the many thousands who actually traveled the clandestine network.

Due to the risk of discovery, information about routes and safe havens was passed along by word of mouth. Southern newspapers of the day were often filled with pages of notices soliciting information about escaped slaves and offering sizable rewards for their capture and return. Federal marshals and professional bounty hunters known as slave catchers pursued fugitives as far as the Canadian border.

The risk of capture was not limited solely to actual fugitives. Because strong, healthy blacks in their prime working and reproductive years were highly valuable commodities, it was not unusual for free blacks — both freedmen (former slaves) and those who had lived their entire lives in freedom — to be kidnapped and sold into slavery. "Certificates of freedom" — signed, notarized statements attesting to the free status of individual blacks — could easily be destroyed and thus afforded their owners little protection. Moreover, under the terms of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, when suspected fugitives were seized and brought to a special magistrate known as a commissioner, they had no right to a jury trial and could not testify in their own behalf; the marshal or private slave-catcher only needed to swear an oath to acquire a writ of replevin, for the return of property.

Nevertheless, Congress believed the fugitive slave laws were necessary because of the lack of cooperation by the police, courts, and public outside of the Deep South. States such as Michigan passed laws interfering with the federal bounty system, which politicians from the South felt was grossly inadequate, and this became a key motivation for secession. In some parts of the North slave-catchers needed police protection to carry out their federal authority. Even in states that resisted cooperation with slavery laws, though, blacks were often unwelcome; Indiana passed a constitutional amendment that barred blacks from settling in that state.

Terminology

The Underground Railroad developed its own jargon, which continued the railway metaphor:

- People who helped slaves find the railroad were "agents" (or "shepherds")

- Guides were known as "conductors"

- Hiding places were "stations"

- "Stationmasters" hid slaves in their homes

- Escaped slaves were referred to as "passengers" or "cargo"

- Slaves would obtain a "ticket"

- Financial benefactors of the Railroad were known as "stockholders".

As well, the Big Dipper asterism, whose "bowl" points to the north star, was known as the drinkin' gourd, and immortalized in a contemporary code tune. The Railroad itself was often known as the "freedom train" or "Gospel train", which headed towards "Heaven" or "the Promised Land"—Canada.

William Still, often called "The Father of the Underground Railroad", helped hundreds of slaves to escape (as many as 60 a month), sometimes hiding them in his Philadelphia home. He kept careful records, including short biographies of the people, that contained frequent railway metaphors. He maintained correspondence with many of them, often acting as a middleman in communications between escaped slaves and those left behind. He then published these accounts in the book The Underground Railroad in 1872.

According to Still, messages were often encoded so that only those active in the railroad would fully understand their meanings. For example, the following message, "I have sent via at two o'clock four large and two small hams", indicated that four adults and two children were sent by train from Harrisburg to Philadelphia. However, the addition of the word via indicated that they were not sent on the regular train, but rather via Reading, Pennsylvania. In this case, the authorities went to the regular train station in an attempt to intercept the runaways, while Still was able to meet them at the correct station and guide them to safety, where they eventually escaped to Canada.

Folklore

Since the 1980s, claims have arisen that quilt designs were used to signal and direct slaves to escape routes and assistance. The quilt design theory is disputed. The first published work documenting an oral history source was in 1999 and the first publishing is believed to be a 1980 children's book[6], so it is difficult to evaluate the veracity of these claims and it is not accepted by quilt historians.[citation needed] There is no contemporary evidence of any sort of quilt code, and quilt historians such as Pat Cummings and Barbara Brackman have raised serious questions about the idea. In addition, Underground Railroad historian Giles Wright has published a pamphlet debunking the quilt code.[citation needed]

Many accounts also mention spirituals and other songs that contained coded information intended to help navigate the railroad.[citation needed] Songs such as "Steal Away" and other field songs were often passed down purely orally, and others, like "Follow the Drinking Gourd," were published after the days of the Railroad.[6] Tracing their origins and meanings is difficult.[citation needed] In any case, many African-American songs of the period deal with themes of freedom and escape, and distinguishing coded information from expression and sentiment may not be possible.[citation needed]

Legal and political

When frictions between North and South culminated in the American Civil War, many blacks, slave and free, fought with the Union Army. Following passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, in some cases the Underground Railroad operated in reverse as fugitives returned to the United States.

Arrival in Canada

Estimates vary widely, but at least 30,000 slaves escaped to Canada via the Underground Railroad.[7] The largest group settled in Upper Canada (called Canada West from 1841, and today southern Ontario), where numerous African Canadian communities developed. These were generally in the triangular region bounded by Toronto, Niagara Falls, and Windsor. Nearly 1,000 refugees settled in Toronto, and several rural villages made up mostly of ex-slaves were established in Chatham-Kent and Essex County.

Important black settlements also developed in more distant British colonies (now parts of Canada). These included Nova Scotia, Lower Canada (present-day Quebec), as well as Vancouver Island, where Governor James Douglas encouraged black immigration because of his opposition to slavery and because he hoped a significant black community would form a bulwark against those who wished to unite the island with the United States.

Upon arriving at their destinations, many fugitives were disappointed. While the British colonies had no slavery, discrimination was still common. Many of the new arrivals had great difficulty finding jobs, in part because of mass European immigration at the time, and overt racism was common.

With the outbreak of the Civil War in the United States, many black refugees enlisted in the Union Army and, while some later returned to Canada, many remained in the United States. Thousands of others returned to the American South after the war ended. The desire to reconnect with friends and family was strong, and most were hopeful about the changes emancipation and Reconstruction would bring.

Notable people

|

Notable locations

Contemporary literature

- 1829 Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World by David Walker (a call for resistance to slavery in Georgia)

- 1832 The Planter's Northern Bride by Caroline Lee Hentz

- 1852 Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Related events

- 1776 – Declaration of Independence

- 1820 – Missouri Compromise

- 1850 – Compromise of 1850

- 1850 – Fugitive Slave Act

- 1854 – Kansas-Nebraska Act

- 1857 – Dred Scott Decision

- 1858 – Oberlin-Wellington Rescue

- 1860 – Abraham Lincoln of Illinois becomes the first Republican U.S. President

- 1861 through 1865 – American Civil War

- 1863 – Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Lincoln

- 1865 – Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

See also

- National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

- Reverse Underground Railroad

- List of notable opponents of slavery

- Slavery in Canada

- Alice M. Ward Library

- Boston African American National Historic Site

- John Freeman Walls Historic Site

References

- ^ "Underground Railroad" (HTML). dictionary.com. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

[American Heritage Dictionary:] A network of houses and other places that abolitionists used to help slaves escape to freedom in the northern states or in Canada

- ^ a b "The Underground Railroad" (HTML). Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ^ PURPOSE AND BACKGROUND. Underground Railroad: Special Research Study Nation Park Service

- ^ The Fugitive Slave Law African-American History, pg. 2. About.com

- ^ From slavery to freedom see pg. 3 #5. The Grapevine.

- ^ a b School Library Journal: "History That Never Happened." Marc Aronson, April 2007.

- ^ "Settling Canada Underground Railroad" (HTML with Javascript). Historica.

Between 1840 and 1860, more than 30,000 American slaves came secretly to Canada and freedom

- 1998

- Forbes, Ella. But We Have No Country: The 1851 Christiana Pennsylvania Resistance. Africana Homestead Legacy Publishers.

- 2000

- Chadwick, Bruce. Traveling the Underground Railroad: A Visitor's Guide to More Than 300 Sites. Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-2093-0.

- 2001

- Blight, David W. Passages to Freedom: The Underground Railroad in History and Memory. Smithsonian Books. ISBN 1-58834-157-7.

- 2002

- Hudson, J. Blaine. Fugitive Slaves and the Underground Railroad in the Kentucky Borderland. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1345-X.

- 2003

- Hendrick, George, and Willene Hendrick. Fleeing for Freedom: Stories of the Underground Railroad As Told by Levi Coffin and William Still. Ivan R. Dee Publisher. ISBN 1-56663-546-2.

- 2004

- Hagedorn, Ann. Beyond the River: The Untold Story of the Heroes of the Underground Railroad. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-87066-5.

- Griffler, Keith P. Front Line of Freedom: African Americans and the Forging of the Underground Railroad in the Ohio Valley. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2298-8.

- 2005

- Bordewich, Fergus M. "Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America". Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-052430-8.

- Michael, Peter H. "An American Family of the Underground Railroad". Author House. ISBN 1-4208-4907-7.

Further reading

- Underground Railroad, 1872, by William Still, from Project Gutenberg (classic book documenting the Underground Railroad operations in Philadelphia)

- Stories of the Underground Railroad, 1941, by Anna L. Curtis (stories about Thomas Garrett, a famous agent on the Underground Railroad)

- "Robert Hayden: His Day is Now!" contains the poet's classic "Runagate, Runagate" ("Renegade, Renegade")

Folklore/Myth:

- New Jersey's Underground Railroad Myth-Buster: Giles Wright is on a Mission to Fine Tune Black History

- Putting it in Perspective: The Symbolism of Underground Railroad quilts

- Underground Railroad Quilts & Abolitionist Fairs

- Documentary Evidence is Missing on Underground Railroad Quilts

External links

- Africanaonline - A study of the Undergound Railroad.

- Tracks to Freedom: Canada and the Underground Railroad

- Annual historic re-creation of Underground Railroad in Sugar Grove, Pennsylvania

- Friends of the Underground Railroad

- The William Still National Underground Railroad Foundation

- National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

- National Park Service: Aboard the Underground Railroad

- National Geographic: Underground Railroad

- Maryland's Cooling Springs Farm: The Story of a Still-Existing Underground Railroad Safe-House

- Underground Railroad in Canada

- Tracks to Freedom - Canada.com special on the Underground Railway in Canada

- Ontario's Underground Railroad - Includes an interactive map, a tour, and more.

- Underground Railroad in Westfield, Indiana - Includes Anti-Slavery Friends Cemetery list and more

- Prospect Place mansion, Underground Railroad safehouse in Trinway, Ohio

- Underground Railroad Research Institute at Georgetown College

- The Oberlin Heritage Center-Learn about Oberlin's role in the Underground Railroad, the abolition movement, and more.

- Pathways to Freedom: Maryland and the Underground Railroad - educational website developed by Maryland Public Television

- NPS Underground Railroad Sites