Microphone

A microphone, sometimes referred to as a mike or mic (both IPA pronunciation: [maɪk]), is an acoustic to electric transducer or sensor that converts sound into an electrical signal.

Microphones are used in many applications such as telephones, tape recorders, hearing aids, motion picture production, live and recorded audio engineering, in radio and television broadcasting and in computers for recording voice, VoIP, and for non-acoustic purposes such as ultrasonic checking.

History

Several early inventors built primitive microphones (then called transmitters) prior to Alexander Bell, but the first commercially practical microphone was the carbon microphone conceived in October 1876 by Thomas Edison. Many early developments in microphone design took place at Bell Laboratories. See also Timeline of the telephone.

Principle of operation

A microphone is a device made to capture waves in air, water (hydrophone) or hard material and translate them into an electrical signal. The most common method is via a thin membrane producing some proportional electrical signal. Most microphones in use today for audio use electromagnetic generation (dynamic microphones), capacitance change (condenser microphones) or piezoelectric generation to produce the signal from mechanical vibration. The piezoelectric microphone is now largely obsolete. However, piezoelectric pickups are still the most common device for amplifying acoustic guitars, usually placed under the guitar's saddle or embedded in the bridge.

Microphone varieties

Condenser, capacitor or electrostatic microphones

Technology

In a condenser microphone, also known as a capacitor microphone, the diaphragm acts as one plate of a capacitor, and the vibrations produce changes in the distance between the plates.

There are two methods of extracting an audio output from the transducer thus formed. They are known as DC biased and RF (or HF) condenser microphones.

DC-biased microphone operating principle

The plates are biased with a fixed charge (Q). The voltage maintained across the capacitor plates changes with the vibrations in the air, according to the capacitance equation:

where Q = charge in coulombs, C = capacitance in farads and V = potential difference in volts. The capacitance of the plates is inversely proportional to the distance between them for a parallel-plate capacitor. (See capacitance for details.)

A nearly constant charge is maintained on the capacitor. As the capacitance changes, the charge across the capacitor does change very slightly, but at audible frequencies it is sensibly constant. The capacitance of the capsule and the value of the bias resistor form a filter which is highpass for the audio signal, and lowpass for the bias voltage. Note that the time constant of a RC circuit equals the product of the resistance and capacitance.

Within the time-frame of the capacitance change (on the order of 100 μs), the charge thus appears practically constant and the voltage across the capacitor adjusts itself instantaneously to reflect the change in capacitance. The voltage across the capacitor varies above and below the bias voltage. The voltage difference between the bias and the capacitor is seen across the series resistor. The voltage across the resistor is amplified for performance or recording.

RF condenser microphone operating principle

In a DC-biased condenser microphone, a high capsule polarisation voltage is necessary. In contrast, RF condenser microphones use a comparatively low RF voltage, generated by a low-noise oscillator. The oscillator is frequency modulated by the capacitance changes produced by the sound waves moving the capsule diaphragm. Demodulation yields a low-noise audio frequency signal with a very low source impedance. This technique achieves better low frequency response - in fact it will theoretically operate down to DC.

The RF biasing process results in a lower electrical impedance capsule, a useful byproduct of which is that RF condenser microphones can be operated in damp weather conditions which would effectively short out a DC biased microphone. The Sennheiser "MKH" series of microphones use the RF biased technique.

Usage

Condenser microphones span the range from cheap throw-aways to high-fidelity quality instruments. They generally produce a high-quality audio signal and are now the popular choice in laboratory and studio recording applications. They require a power source, provided either from microphone inputs as phantom power or from a small battery. Professional microphones often sport an external power supply for reasons of quality perception. Power is necessary for establishing the capacitor plate voltage, and is also needed for internal amplification of the signal to a useful output level. Condenser microphones are also available with two diaphragms, the signals from which can be electrically connected such as to provide a range of polar patterns (see below), such as cardioid, omnidirectional and figure-eight. It is also possible to vary the pattern smoothly with some microphones, for example the Røde NT2000.

Electret condenser microphones

An electret microphone is a relatively new type of capacitor microphone invented at Bell laboratories in 1962 by Gerhard Sessler and Jim West[1]. An electret is a ferroelectric material that has been permanently electrically charged or polarized. The name comes from electrostatic and magnet; a static charge is embedded in an electret by alignment of the static charges in the material, much the way a magnet is made by aligning the magnetic domains in a piece of iron. They are used in many applications, from high-quality recording and lavalier use to built-in microphones in small sound recording devices and telephones. Though electret microphones were once low-cost and considered low quality, the best ones can now rival capacitor microphones in every respect and can even offer the long-term stability and ultra-flat response needed for a measuring microphone. Unlike other capacitor microphones, they require no polarizing voltage, but normally contain an integrated preamplifier which does require power (often incorrectly called polarizing power or bias). This preamp is frequently phantom powered in sound reinforcement and studio applications. While few electret microphones rival the best DC-polarized units in terms of noise level, this is not due to any inherent limitation of the electret. Rather, mass production techniques needed to produce electrets cheaply don't lend themselves to the precision needed to produce the highest quality microphones.

Dynamic microphones

Dynamic microphones work via electromagnetic induction. They are robust, relatively inexpensive and resistant to moisture, and for this reason they are widely used on-stage by singers. There are two basic types: the moving coil microphone and the ribbon microphone.

Moving coil microphones

Technology

The dynamic principle is exactly the same as in a loudspeaker, only reversed. A small movable induction coil, positioned in the magnetic field of a permanent magnet, is attached to the diaphragm. When sound enters through the windscreen of the microphone, the sound wave moves the diaphragm. When the diaphragm vibrates, the coil moves in the magnetic field, producing a varying current in the coil through electromagnetic induction. A single dynamic membrane will not respond linearly to all audio frequencies. Some microphones for this reason utilize multiple membranes for the different parts of the audio spectrum and then combine the resulting signals. Combining the multiple signals correctly is difficult and designs that do this are rare and tend to be expensive. There are on the other hand several designs that are more specifically aimed towards isolated parts of the audio spectrum. AKG D112 is for example designed for bass content rather than treble. In audio engineering several kinds of microphones are often used at the same time to get the best result.

Ribbon microphones

In ribbon microphones a thin, usually corrugated metal ribbon is suspended in a magnetic field. The ribbon is electrically connected to the microphone's output, and its vibration within the magnetic field generates the electrical signal. Ribbon microphones are similar to moving coil microphones in the sense that both produce sound by means of magnetic induction. Basic ribbon microphones detect sound in a bidirectional (also called figure-eight) pattern because the ribbon, which is open to sound both front and back, responds to the pressure gradient rather than the sound pressure. Though the symmetrical front and rear pickup can be a nuisance in normal stereo recording, the high side rejection can be used to advantage by positioning a ribbon microphone horizontally, for example above cymbals, so that the rear lobe picks up only sound from the cymbals. Crossed figure 8, or Blumlein stereo recording is gaining in popularity, and the figure 8 response of a ribbon microphone is ideal for that application. Other directional patterns are produced by enclosing one side of the ribbon in an acoustic trap or baffle, allowing sound to reach only one side. Older ribbon microphones, some of which still give very high quality sound reproduction, and were once valued for this reason, but a good low-frequency response could only be obtained only if the ribbon is suspended very loosely, and this made them fragile. Modern ribbon materials have now been introduced that eliminate those concerns. Protective wind screens can reduce the danger of damaging a vintage ribbon, and also reduce plosive artifacts in the recording. Properly designed wind screens produce negligible treble attenuation.

In common with other classes of dynamic microphone, ribbon microphones don't require phantom power; in fact, this voltage can damage some older ribbon microphones. (There are some new modern ribbon microphone designs which incorporate a preamplifier and therefore do require phantom power, also there are new ribbon materials available that are immune to wind blasts and phantom power.)

Carbon microphones

A carbon microphone, formerly used in telephone handsets, is a capsule containing carbon granules pressed between two metal plates. A voltage is applied across the metal plates, causing a small current to flow through the carbon. One of the plates, the diaphragm, vibrates in sympathy with incident sound waves, applying a varying pressure to the carbon. The changing pressure deforms the granules, causing the contact area between each pair of adjacent granules to change, and this causes the electrical resistance of the mass of granules to change. The changes in resistance cause a corresponding change in the voltage across the two plates, and hence in the current flowing through the microphone, producing the electrical signal. Carbon microphones were once commonly used in telephones; they have extremely low-quality sound reproduction and a very limited frequency response range, but are very robust devices.

Unlike other microphone types, the carbon microphone can also be used as a type of amplifier, using a small amount of sound energy to produce a larger amount of electrical energy. Carbon microphones found use as early telephone repeaters, making long distance phone calls possible in the era before vacuum tubes. These repeaters worked by mechanically coupling a magnetic telephone receiver to a carbon microphone: the faint signal from the receiver was transferred to the microphone, with a resulting stronger electrical signal to send down the line. (One illustration of this amplifier effect was the oscillation caused by feedback, resulting in an audible squeal from the old "candlestick" telephone if its earphone was placed near the carbon microphone.)

Crystal (Piezo) microphones

Technology

A crystal microphone uses the phenomenon of piezoelectricity—the ability of some materials to produce a voltage when subjected to pressure—to convert vibrations into an electrical signal. An example of this is Rochelle salt (potassium sodium tartrate), which is a piezoelectric crystal that works as a transducer, both as a microphone and as a slimline loudspeaker component.

Usage

Crystal microphones used to be commonly supplied with vacuum tube (valve) equipment such as domestic tape recorders. Their high output impedance matched well to the high input impedance of the vacuum tube input stage (10 Megohms was not uncommon). They were difficult to match to early transistor equipment and were quickly supplanted by dynamic microphones for a short while, and later small eletret condenser devices. The high impedance of the crystal microphone made it very susceptable to handling noise, partly from the microphone itself, but also from the handling of the connecting cable.

Piezo transducers are often used as contact microphones to amplify sound from acoustic musical instruments, or to record sounds in unusual environments (underwater, for instance). Saddle mounted pickups on acoustic guitars are generally piezos that are mechanically connected to the strings through the saddle. This type of microphone is not to be confused with magnetic coil pickups commonly visible on typical electric guitars.

Laser microphones

Usage

Laser microphones are new, very rare and expensive, and are most commonly portrayed in movies as spying devices.

Liquid microphones

Technology

Early microphones did not produce intelligible speech, until Alexander Graham Bell made improvements including a variable resistance microphone/transmitter. Bell’s liquid transmitter consisted of a metal cup filled with water with a small amount of sulfuric acid added. A sound wave caused the diaphragm to move, forcing a needle to move up and down in the water. The electrical resistance between the wire and the cup was then inversely proportional to the size of the water meniscus around the submerged needle. Elisha Gray filed a caveat for a version using a brass rod instead of the needle. Other minor variations and improvements were made to the liquid microphone by Majoranna, Chambers, Vanni, Sykes, and Elisha Gray, and one version was even patented by Reginald Fessenden in 1903.

Usage

These were the first working microphones, but they were not practical for commercial application and are utterly obsolete now. It was with a liquid microphone that the famous first phone conversation between Bell and Watson took place. Other inventors, especially Thomas Edison, soon devised superior microphones.

MEMS microphones

The MEMS microphone is also called a microphone chip or silicon microphone. The pressure-sensitive diaphragm is etched directly on a silicon chip by MEMS (MicroElectrical-Mechanical Systems) techniques[citation needed], and is usually accompanied with integrated preamplifier. Most MEMS microphones are modern embodiments of the standard condenser microphone. Often MEMS mics have a built in ADC on the same CMOS chip making the chip a digital microphone and easily integrated into modern digital products. Major manufacturers using MEMS manufacturing for silicon microphones are Akustica (AKU200x), Infineon (SMM310 product), Knowles Electronics and Sonion MEMS.

Speakers as microphones

A loudspeaker, a transducer that turns an electrical signal into sound waves, is the functional opposite of a microphone. Since a conventional speaker is constructed much like a dynamic microphone (with a diaphragm, coil and magnet), speakers can actually work "in reverse" as microphones. The result, though, is a microphone with poor quality, limited frequency response (particularly at the high end), and poor sensitivity.

In practical use, speakers are sometimes used as microphones in such applications as intercoms or walkie-talkies, where high quality and sensitivity are not needed. However, there is at least one other novel application of this principle; using a medium-size woofer placed closely in front of a "kick" (bass drum) in a drum set to act as a microphone. This has been commercialized with the Yamaha "Subkick".[1]

Capsule design and directivity

The shape of the microphone defines its directivity. Inner elements are of major importance and concerns the structural shape of the capsule, outer elements may be the interference tube.

A pressure gradient microphone is a microphone in which both sides of the diaphragm are exposed to the incident sound and the microphone is therefore responsive to the pressure differential (gradient) between the two sides of the membrane. Sound incident parallel to the plane of the diaphragm produces no pressure differential, giving pressure-gradient microphones their characteristic figure-eight directional patterns.

The capsule of a pressure microphone however is closed on one side, which results in an omnidirectional pattern.

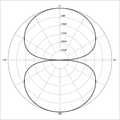

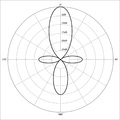

Microphone polar patterns

Regarding directionality, omnidirectional microphones are pressure transducers, whereas all others are pressure gradient transducers or a combination between the two.

Common polar patterns for microphones (Microphone facing top of page in diagram, parallel to page):

-

Omnidirectional -

Subcardioid -

Cardioid -

Supercardioid -

Hypercardioid -

Bi-directional -

Shotgun

A microphone's directionality or polar pattern indicates how sensitive it is to sounds arriving at different angles about its central axis. The above polar patterns represent the locus of points that produce the same signal level output in the microphone if a given sound pressure level is generated from that point. How the physical body of the microphone is oriented relative to the diagrams depends on the microphone design. For large-membrane microphones such as in the Oktava (pictured above), the upward direction in the polar diagram is usually perpendicular to the microphone body, commonly known as "side fire". For small diaphragm microphones such as the Shure (also pictured above), it usually extends from the axis of the microphone commonly known as "end fire".

Some microphone designs combine several principles in creating the desired polar pattern. This ranges from shielding (meaning diffraction/dissipation/absorption) by the housing itself to electronically combining dual membranes.

An omnidirectional microphone's response is generally considered to be a perfect sphere in three dimensions. In the real world, this is not the case. As with directional microphones, the polar pattern for an "omnidirectional" microphone is a function of frequency. The body of the microphone is not infinitely small and, as a consequence, it tends to get in its own way with respect to sounds arriving from the rear, causing a slight flattening of the polar response. This flattening increases as the diameter of the microphone (assuming it's cylindrical) reaches the wavelength of the frequency in question. Therefore, the smallest diameter microphone will give the best omnidirectional characteristics at high frequencies. The wavelength of sound at 10 kHz is little over an inch (3.4 cm) so the smallest measuring microphones are often 1/4" (6 mm) in diameter, which practically eliminates directionality even up to the highest frequencies. Omnidirectional microphones, unlike cardioids, do not employ resonant cavities as delays, and so can be considered the "purest" microphones in terms of low coloration; they add very little to the original sound. Being pressure-sensitive they can also have a very flat low-frequency response down to 20 Hz or below. Pressure-sensitive microphones also respond much less to wind noise than directional (velocity sensitive) microphones.

A unidirectional microphone is sensitive to sounds from only one direction. The diagram above illustrates a number of these patterns. The microphone faces upwards in each diagram. The sound intensity for a particular frequency is plotted for angles radially from 0 to 360°. (Professional diagrams show these scales and include multiple plots at different frequencies. These diagrams just provide an overview of the typical shapes and their names.)

The most common unidirectional microphone is a cardioid microphone, so named because the sensitivity pattern is heart-shaped (see cardioid). A hyper-cardioid is similar but with a tighter area of front sensitivity and a tiny lobe of rear sensitivity. These two patterns are commonly used as vocal or speech microphones, since they are good at rejecting sounds from other directions.

Figure 8 or bi-directional microphones receive sound from both the front and back of the element. Most ribbon microphones are of this pattern.

Shotgun microphones are the most highly directional. They have small lobes of sensitivity to the left, right, and rear but are significantly more sensitive to the front. This results from placing the element inside a tube with slots cut along the side; wave-cancellation eliminates most of the off-axis noise. Shotgun microphones are commonly used on TV and film sets, and for field recording of wildlife.

An omnidirectional microphone is a pressure transducer; the output voltage is proportional to the air pressure at a given time.

On the other hand, a figure-8 pattern is a pressure gradient transducer; A sound wave arriving from the back will lead to a signal with a polarity opposite to that of an identical sound wave from the front. Moreover, shorter wavelengths (higher frequencies) are picked up more effectively than lower frequencies.

A cardioid microphone is effectively a superposition of an omnidirectional and a figure-8 microphone; for sound waves coming from the back, the negative signal from the figure-8 cancels the positive signal from the omnidirectional element, whereas for sound waves coming from the front, the two add to each other. A hypercardioid microphone is similar, but with a slightly larger figure-8 contribution.

Since pressure gradient transducer microphones are directional, at distances of a few centimeters of the sound source results in a bass boost. This is known as the proximity effect[citation needed].

Application-specific microphone designs

A lavalier microphone is made for hands-free operation. These small microphones are worn on the body and held in place either with a lanyard worn around the neck or a clip fastened to clothing. The cord may be hidden by clothes and either run to an RF transmitter in a pocket or clipped to a belt (for mobile use), or run directly to the mixer (for stationary applications).

A wireless microphone is one which does not use a cable. It usually transmits its signal using a small FM radio transmitter to a nearby receiver connected to the sound system, but it can also use infrared light if the transmitter and receiver are within sight of each other.

A contact microphone is designed to pick up vibrations directly from a solid surface or object, as opposed to sound vibrations carried through air. One use for this is to detect sounds of a very low level, such as those from small objects or insects. The microphone commonly consists of a magnetic (moving coil) transducer, contact plate and contact pin. The contact plate is placed against the object from which vibrations are to be picked up; the contact pin transfers these vibrations to the coil of the transducer. Contact microphones have been used to pick up the sound of a snail's heartbeat and the footsteps of ants. A portable version of this microphone has recently been developed.

A throat microphone is a variant of the contact microphone, used to pick up speech directly from the throat, around which it is strapped. This allows the device to be used in areas with ambient sounds that would otherwise make the speaker inaudible.

A parabolic microphone uses a parabolic reflector to collect and focus sound waves onto a microphone receiver, in much the same way that a parabolic antenna (e.g. satellite dish) does with radio waves. Typical uses of this microphone, which has unusually focused front sensitivity and can pick up sounds from many meters away, include nature recording, outdoor sporting events, eavesdropping, law enforcement, and even espionage. Parabolic microphones are not typically used for standard recording applications, because they tend to have poor low-frequency response as a side effect of their design.

Connectivity

Connectors

The most common connectors used by microphones are:

- Male XLR connector on professional microphones

- ¼ inch mono phone plug on less expensive consumer microphones

- 3.5 mm (Commonly referred to as 1/8 inch mini) mono mini phone plug on very inexpensive and computer microphones

Some microphones use other connectors, such as 1/4 inch TRS (tip ring sleeve), 5-pin XLR, or stereo mini phone plug (1/8 inch TRS) on some stereo microphones. Some lavalier microphones use a proprietary connector for connection to a wireless transmitter. Since 2005, professional-quality microphones with USB connections have begun to appear, designed for direct recording into computer-based software studios.

Impedance matching

Microphones have an electrical characteristic called impedance, measured in ohms (Ω), that depends on the design. Typically, the rated impedance is stated.[2] Low impedance is considered under 600 Ω. Medium impedance is considered between 600 Ω and 10 kΩ. High impedance is above 10 kΩ.

Most professional microphones are low impedance, about 200 Ω or lower. Low-impedance microphones are preferred over high impedance for two reasons: one is that using a high-impedance microphone with a long cable will result in loss of high frequency signal due to the capacitance of the cable; the other is that long high-impedance cables tend to pick up more hum (and possibly radio-frequency interference (RFI) as well). However, some equipment, such as vacuum tube guitar amplifiers, has an input impedance that is inherently high, requiring the use of a high impedance microphone or a matching transformer. Nothing will be damaged if the impedance between microphone and other equipment is mismatched; the worst that will happen is a reduction in signal or change in frequency response.

To get the best sound in most cases, the impedance of the microphone must be distinctly lower (by a factor of at least five) than that of the equipment to which it is connected. Most microphones are designed not to have their impedance "matched" by the load to which they are connected; doing so can alter their frequency response and cause distortion, especially at high sound pressure levels. There are transformers (confusingly called matching transformers) that adapt impedances for special cases such as connecting microphones to DI units or connecting low-impedance microphones to the high-impedance inputs of certain amplifiers, but microphone connections generally follow the principle of bridging (voltage transfer), not matching (power transfer). In general, any XLR microphone can usually be connected to any mixer with XLR microphone inputs, and any plug microphone can usually be connected to any jack that is marked as a microphone input, but not to a line input. This is because the signal level of a microphone is typically 40-60 dB lower (a factor of 100 to 1000) than a line input. Microphone inputs include the necessary amplification circuitry to deal with these very low level signals. The exception to these comments is in the case of certain ribbon and dynamic microphones which are most linear when operated into a load of known impedance [3]

Digital microphone interface

The AES 42 standard, published by the Audio Engineering Society, defines a digital interface for microphones. Microphones conforming to this standard directly output a digital audio stream through an XLR male connector, rather than producing an analog output. Digital microphones may be used either with new equipment which has the appropriate input connections conforming to the AES 42 standard, or else by use of a suitable interface box. Studio-quality microphones which operate in accordance with the AES 42 standard are now appearing from a number of microphone manufacturers.

Measurements and specifications

Because of differences in their construction, microphones have their own characteristic responses to sound. This difference in response produces non-uniform phase and frequency responses. In addition, microphones are not uniformly sensitive to sound pressure, and can accept differing levels without distorting. Although for scientific applications microphones with a more uniform response are desirable, this is often not the case for music recording, as the non-uniform response of a microphone can produce a desirable coloration of the sound. There is an international standard for microphone specifications,[4] but few manufacturers adhere to it. As a result, comparison of published data from different manufacturers is difficult because different measurement techniques are used. The Microphone Data Website has collated the technical specifications complete with pictures, response curves and technical data from the microphone manufacturers for every currently listed microphone, and even a few obsolete models, and shows the data for them all in one common format for ease of comparison.[2]. Caution should be used in drawing any solid conclusions from this or any other published data, however, unless it is known that the manufacturer has supplied specifications in accordance with IEC 60268-4.

A frequency response diagram plots the microphone sensitivity in decibels over a range of frequencies (typically at least 0–20 kHz), generally for perfectly on-axis sound (sound arriving at 0° to the capsule). Frequency response may be less informatively stated textually like so: "30 Hz–16 kHz ±3 dB". This is interpreted as a (mostly) linear plot between the stated frequencies, with variations in amplitude of no more than plus or minus 3 dB. However, one cannot determine from this information how smooth the variations are, nor in what parts of the spectrum they occur. Note that commonly-made statements such as "20 Hz–20 kHz" are meaningless without a decibel measure of tolerance. Directional microphones' frequency response varies greatly with distance from the sound source, and with the geometry of the sound source. IEC 60268-4 specifies that frequency response should be measured in plane progressive wave conditions (very far away from the source) but this is seldom practical. Close talking microphones may be measured with different sound sources and distances, but there is no standard and therefore no way to compare data from different models unless the measurement technique is described.

The self-noise or equivalent noise level is the sound level that creates the same output voltage as the microphone does in the absence of sound. This represents the lowest point of the microphone's dynamic range, and is particularly important should you wish to record sounds that are quiet. The measure is often stated in dB(A), which is the equivalent loudness of the noise on a decibel scale frequency-weighted for how the ear hears, for example: "15 dBA SPL" (SPL means sound pressure level relative to 20 micropascals). The lower the number the better. Some microphone manufacturers state the noise level using ITU-R 468 noise weighting, which more accurately represents the way we hear noise, but gives a figure some 11 to 14 dB higher. A quiet microphone will measure typically 20 dBA SPL or 32 dB SPL 468-weighted. The state of the art has recently improved with the NT1-A microphone from Røde, which has a noise level of 5dBA.

The maximum SPL (sound pressure level) the microphone can accept is measured for particular values of total harmonic distortion (THD), typically 0.5%. This is generally inaudible, so one can safely use the microphone at this level without harming the recording. Example: "142 dB SPL peak (at 0.5% THD)". The higher the value, the better, although microphones with a very high maximum SPL also have a higher self-noise.

The clipping level is perhaps a better indicator of maximum usable level, as the 1% THD figure usually quoted under max SPL is really a very mild level of distortion, quite inaudible especially on brief high peaks. Harmonic distortion from microphones is usually of low-order (mostly third harmonic) type, and hence not very audible even at 3-5%. Clipping, on the other hand, usually caused by the diaphragm reaching its absolute displacement limit (or by the preamplifier), will produce a very harsh sound on peaks, and should be avoided if at all possible. For some microphones the clipping level may be much higher than the max SPL.

The dynamic range of a microphone is the difference in SPL between the noise floor and the maximum SPL. If stated on its own, for example "120 dB", it conveys significantly less information than having the self-noise and maximum SPL figures individually.

Sensitivity indicates how well the microphone converts acoustic pressure to output voltage. A high sensitivity microphone creates more voltage and so will need less amplification at the mixer or recording device. This is a practical concern but is not directly an indication of the mic's quality, and in fact the term sensitivity is something of a misnomer, 'transduction gain' being perhaps more meaningful, (or just "output level") because true sensitivity will generally be set by the noise floor, and too much "sensitivity" in terms of output level will compromise the clipping level. There are two common measures. The (preferred) international standard is made in millivolts per pascal at 1 kHz. A higher value indicates greater sensitivity. The older American method is referred to a 1 V/Pa standard and measured in plain decibels, resulting in a negative value. Again, a higher value indicates greater sensitivity, so −60 dB is more sensitive than −70 dB.

Measurement microphones

Some microphones are intended for use as standard measuring microphones for the testing of speakers and checking noise levels etc. These are calibrated transducers and will usually be supplied with a calibration certificate stating absolute sensitivity against frequency.

Microphone calibration techniques

Pistonphone apparatus

A pistonphone is an acoustical calibrator (sound source) using a closed coupler to generate a precise sound pressure for the calibration of instrumentation microphones. The principle relies on a piston mechanically driven to move at a specified rate on a fixed volume of air to which the microphone under test is exposed. The air is assumed to be compressed adiabatically and the SPL in the chamber can be calculated from the adiabatic gas law, which requires that the product of the pressure P with V raised to the power gamma be constant; here gamma is the ratio of the specific heat of air at constant pressure to its specific heat at constant volume. The pistonphone method only works at low frequencies, but it can be accurate and yields an easily calculable sound pressure level. The standard test frequency is usually around 250 Hz.

Reciprocal method

This method relies on the reciprocity of one or more microphones in a group of 3 to be calibrated. It can still be used when only one of the microphones is reciprocal (exhibits equal response when used as a microphone or as a loudspeaker).

Microphone array and array microphones

A microphone array is a system of several closely-positioned microphones.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Microphone windscreens

Windscreens are used to protect microphones that would otherwise be buffeted by wind or vocal plosives (from consonants such as "P", "B", etc.). Windscreens are often made of soft open-cell polyester or polyurethane foam because of the inexpensive, disposable nature of the foam. Finer windscreens are made of thin plastic screening held out at a distance from the diaphragm by a framework or cage fitted to the microphone body. Pop filters or pop screens are used in controlled studio environments to keep plosives down when recording. Foam windscreens are integral to some microphone designs such as the Shure SM58 which has a thin foam layer just inside the wire mesh ball enclosing the diaphragm. Optional windscreens are often available from the manufacturer and third parties. A very visible example of optional accessory windscreen is the A2WS from Shure, one of which is fitted over each of the two SM57s used on the United States Presidential lectern.[5]

Large, hollow "blimp" or "zeppelin" windscreens are used to surround boom microphones for location audio such as nature recording, electronic news gathering and for film and video shoots. They can cut wind noise by as much as 25 dB, especially low-frequency noise. A refinement of the blimp windscreen is the addition of a synthetic furry cover which can cut wind noise down by a further 12 dB.[6]

Vocalists often use windscreens on handheld microphones to cut plosive breath noise that involve sharp outward airflow from the mouth. The necessity of a windscreen increases the closer a vocalist brings the microphone to their lips. Singers can be trained to soften their plosives, in which case they don't need a windscreen for any reason other than wind.

Windscreens are used extensively in outdoor concert sound and location recording where wind is an unpredictable factor.

Highly directional microphones benefit the most from windscreens, more so than omnidirectional mics which aren't as vulnerable to wind noise.

One disadvantage of windscreens is that the microphone's high frequency response is attenuated by a small amount relative to how dense the protective layer is. Another disadvantage is that windscreens are often fragile, lightweight and/or small, making it easy to damage or lose them. Poorly fitted windscreens can slip to expose microphone porting to wind action and can fall off completely. The polyurethane foam deteriorates over time, requiring replacement in older microphones undergoing refurbishment. Windscreens collect dirt and moisture in their open cells and must be cleaned from time to time to prevent high frequency loss, bad odor and unhealthy conditions for the artist. On the other hand, a major advantage of concert vocalist windscreens is that one can quickly change to a clean windscreen between artists, reducing the chance of transferring germs. Windscreens of various colors can be used to distinguish one microphone from another on a busy, active stage.

See also

- Loudspeaker — The inverse of a microphone

- Microphone practice

- A-weighting

- Button microphone

- ITU-R 468 noise weighting

- Nominal impedance — Information about impedance matching for audio components

- Sound pressure level

- Wireless microphone

- XLR connector — The 3-pin variant of which is used for connecting microphones

External links

- Info, Pictures and Soundbytes from vintage microphones

- Microphone construction and basic placement advice

- History of the Microphone

- Microphone sensitivity conversion — dB re 1 V/Pa and transfer factor mV/Pa

- Large vs. Small Diaphragms in Omnidirectional Microphones

- Microphone Expressions Lexicon

References

- ^ "Electret Microphone Turns 40"

- ^ International Standard IEC 60268-4

- ^ Robertson, A. E.: "Microphones" Illiffe Press for BBC, 1951-1963

- ^ International Standard IEC 60268-4

- ^ http://www.shure.com/ProAudio/Products/Accessories/us_pro_A2WS-BLK_content

- ^ http://www.rycote.com/products/windshield/