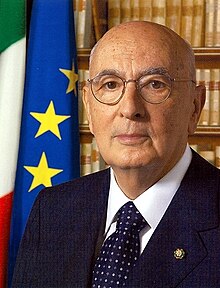

Giorgio Napolitano

Giorgio Napolitano | |

|---|---|

| |

| XI President of the Italian Republic | |

| Assumed office May 15 2006 | |

| Prime Minister | Romano Prodi |

| Preceded by | Carlo Azeglio Ciampi |

| Italian Minister of the Interior | |

| In office May 17 1996 – October 21 1998 | |

| Prime Minister | Romano Prodi |

| Preceded by | Giovanni Rinaldo Coronas |

| Succeeded by | Rosa Russo Jervolino |

| President of the Italian Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office June 3, 1992 – April 14, 1994 | |

| Preceded by | Oscar Luigi Scalfaro |

| Succeeded by | Irene Pivetti |

| Lifetime Senator | |

| In office November 23, 2005 – May 15, 2006 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 300px June 29, 1925 Naples,Italy |

| Died | 300px |

| Resting place | 300px |

| Political party | Democratic Party |

| Spouse | Clio Maria Bittoni |

| Children | Giulio Napolitano Giovanni Napolitano |

| Parent |

|

| Residence(s) | Quirinal Palace, Rome, Italy |

| Alma mater | University of Naples Federico II |

| Profession | Politics |

Giorgio Napolitano (born June 29 1925) is an Italian politician and former lifetime senator, the eleventh and current President of the Italian Republic. His election took place on May 10 2006, and his term started with the swearing-in ceremony held on May 15.

Biography before presidency

Early years and World War II

Napolitano was born in Naples, Campania.

In 1942 Napolitano matriculated at the University of Naples Federico II. He adhered to the local Gruppo Universitario Fascista ("University Fascist Group"), where he met his core group of friends, who shared his opposition to Italian fascism. As he would later state, the group "was in fact a true breeding ground of anti-fascist intellectual energies, disguised and to a certain extent tolerated".[1]

A theatre enthusiast since high school, during his university years he contributed a theatrical review to the IX Maggio weekly magazine, and had small parts in plays organised by the Gruppo Universitario Fascista itself.

During the Nazi occupation of Italy in the final period of World War II, he and his circle of friends took part in several actions of the Italian resistance movement against German Nazi and Italian fascist forces. [2] This included occupying the offices of the IX Maggio magazine and using it to publish writings of Karl Marx masked as articles signed by the various components of the group.

From post-war years to the Hungarian revolution

Following the end of the war in 1945, Napolitano joined the PCI (Partito Comunista Italiano, Italian Communist Party). In 1947, he graduated in jurisprudence with a final thesis on political economy, entitled "Il mancato sviluppo industriale del Mezzogiorno dopo l'unità e la legge speciale per Napoli del 1904". (Italian for "The lack of industrial development in the Mezzogiorno following the unification of Italy and the special law of 1904 for Naples").[3]

He was first elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1953 for the electoral division of Naples, and was returned at every election until 1996.[3] He was elected to the National Committee of the party during its eighth national congress in 1956, largely thanks to the support offered by Palmiro Togliatti, who wanted to involve younger politicians in the central direction of the party. He became responsible for the commission for Southern Italy within the National Committee.[4]

Later on in the same year, the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and its military suppression by the Soviet Union occurred. The leadership of the Italian Communist Party labelled the insurgents as counter-revolutionaries, and the party newspaper L'Unità referred to them as "thugs" and "despicable agents provocateurs". Napolitano complied with the party-sponsored position on this matter, a choice he would repeatedly declare to have become uncomfortable with, developing what his autobiography describes as a "grievous self-critical torment". He would reason that his compliance was motivated by concerns about the role of the Italian Communist Party as "inseparable from the fates of the socialist forces guided by the USSR" as opposed to "imperialist" forces.[1]

The decision to support the USSR against the Hungarian revolutionaries generated a split in the Italian Communist Party, and even the CGIL (Italy's largest trade union, then overtly communist in nature) refused to conform to the party-sponsored position and applauded the revolution, on the basis that the eighth national congress of the Italian Communist Party had indeed stated that the "Italian way to socialism" was to be democratic and specific to the nation. These views were supported in the party by Giorgio Amendola, whom Napolitano would always look up to as a teacher. Frequently seen together, Giorgio Amendola and Giorgio Napolitano would jokingly be referred to by friends as (respectively) Giorgio 'o chiatto and Giorgio 'o sicco ("Giorgio the podgy" and "Giorgio the slim" in the Neapolitan dialect).[5]

From the sixties to the dissolution of the Italian Communist Party

Napolitano then became the party's federal secretary in Naples and Caserta and later, between 1966 and 1969, he was coordinator of the secretary's office and of the political office. During the 1970s and the 1980s he was the officer responsible first for culture and later for the economic policy and the international relations of the party.

His political ideas were somewhat moderate in the context of the PCI: in fact he became the leader of the so-called "meliorist wing" (corrente migliorista) of the party, whose members notably included Gerardo Chiaromonte and Emanuele Macaluso. The term migliorista (from migliore, Italian for "better") was coined with a slightly mocking intent.

In the mid-seventies, Napolitano was invited by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to give a lecture, but the then United States ambassador to Italy, John A. Volpe, refused to grant him a visa on account of his membership in the Communist Party. Between 1977 and 1981 Napolitano had some secret meetings with the United States ambassador Richard Gardner, at a time when the PCI was seeking contact with the US administration, in the context of its definitive break with its past relationship with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the beginning of eurocommunism, the attempt to develop a theory and practice more adequate to the democratic countries of Western Europe. In 2006, when Napolitano was elected President of the Italian Republic, Gardner stated to AP Television News that he considered Napolitano "a real statesman", "a true believer in democracy" and "a friend of the United States [who] will carry out his office with impartiality and fairness".[6] Thanks to this role and in part by the good offices of Giulio Andreotti, in the 1980s Napolitano was able to travel to the United States and give lectures at Aspen, Colorado and at Harvard University. He has since visited and lectured in the United States several times.

After the dissolution

After the dissolution of the Italian Communist Party, in 1991, Napolitano joined the Democratic Party of the Left, later Democrats of the Left (Democratici di Sinistra, or DS). Successively, he served as President of the Chamber of Deputies (1992–1994), and between 1996 and 1998 he was the first former Communist to become Minister of the Interior, a role traditionally occupied by Christian Democrats. In this capacity, he took part together with fellow lawmaker and Cabinet Minister Ms. Livia Turco in drafting the government-sponsored law on immigration control (Legislative Decree No. 286 of July 25, 1988), better known as the "Turco-Napolitano bill". He also served as a Member of the European Parliament from 1999 to 2004. In October 2005, he was named senator for life, and was therefore one of the last two to be appointed by President of the Republic Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, together with Sergio Pininfarina.

Election as president

In 2006, his name was frequently suggested for the office of President of the Italian Republic. Napolitano was the second person proposed by the centre-left majority coalition, The Union, in place of Massimo D'Alema, after the chance of a joint vote on D'Alema had been rejected by leaders of the centre-right coalition The House of Freedoms. Even though Napolitano appeared at first a candidate the House of Freedoms could converge on, the proposal was rejected much like that of D'Alema.

The centre-left majority coalition, on May 7 2006, officially endorsed Giorgio Napolitano as its candidate in the special election that began on May 8. The Vatican endorsed him as President through its official newspaper, L'Osservatore Romano, just after the Union named him as its candidate, as did Marco Follini, former secretary of the UDC, the right-leaning Christian party, member of the House of Freedoms.

Napolitano was elected on May 10, in the fourth round of voting—the first round which required only an absolute majority, unlike the former three which required two-thirds of the votes—with 543 votes (out of a possible 1009). He was the first former Communist to become President of Italy, as well as the third Neapolitan after Enrico De Nicola and Giovanni Leone. After his election, expressions of esteem toward his person and his authority as future President of the Italian Republic were made by both members of the Union and of the House of Freedoms (who had issued a blank vote), such as Pier Ferdinando Casini.[7] Nevertheless, some Italian right-wing newspapers, such as il Giornale, expressed concerns about his communist past.[8] He started his term on May 15.

On July 9, 2006, Napolitano was present at the FIFA World Cup final, in which the Italian team defeated France and won its fourth World Cup, and afterwards he joined the players' celebrations. He is the second President of the Italian Republic to be present at a triumphal World Cup final, after Sandro Pertini.

On September 26, 2006, Napolitano made an official visit to Budapest, Hungary, where he paid tribute to the fallen in the 1956 revolution, which he initially opposed as member of the Italian Communist Party, by laying a wreath at Imre Nagy's grave.[9]

On February 10, 2007 a diplomatic crisis arose between Italy and Croatia, after President Napolitano publicly condemned the foibe massacres on the Foibe Memory Day. The European Commission did not comment on this event, but did comment (and partly condemn) the response by Croatian president Stjepan Mesić, who described Napolitano's statement as racist, because Napolitano did not refer either to Slovenians or Croatians as a nation, when he spoke about a "Slavic annexationist aspiration"" for the Julian March[10] (at the time, Slovenians and Croatians fought together in the Yugoslav Resistance Movement). Another matter of debate in Croatia was that the Italian President made awards to relatives of 25 foibe victims, who included the last fascist Italian prefect in Zadar, Vincenzo Serrentino, convicted to death in 1947 in Šibenik.[11] That was seen by Mesić as "historic revisionism" and open support for revanchism. President Napolitano's remarks on the foibe massacres were praised by both centre-left and centre-right in Italy, and both coalitions condemned Mesić's statements, while the whole of Croatia stood by Mesić, who later acknowledged that Napolitano didn't want to put in discussion the Peace Treaty of 1947.

On February 21, 2007, Prime Minister Romano Prodi submitted his resignation after losing a foreign policy vote in the Parliament;[12] Napolitano held talks with the political groups in parliament, and on February 24 rejected the resignation, prompting Prodi to ask for a new vote of confidence.[13] Prodi won the vote in the upper house on February 28[14] and in the lower house on 2 March[15], allowing his cabinet to remain in office.

Trivia

This article contains a list of miscellaneous information. (June 2007) |

- In his youth, Napolitano was an actor. He played in a comedy by Salvatore Di Giacomo and as leading actor in Viaggio a Cardiff by William Butler Yeats, both at Teatro Mercadante in Naples. He later measured himself against Joyce and Eliot.

- He has often been cited as the author of a collection of sonnets in Neapolitan language, published under the pseudonym Tommaso Pignatelli, entitled "Pe cupià ’o chiarfo" ("To mimic the downpour"). He denied this in 1997 and, again, on the occasion of his presidential election, when his staff described the attribution of authoriship to Napolitano as a "journalistic myth".[16]

- He has been nicknamed "Re Umberto" (i.e. "King Umberto") both for his physical likeness to Umberto II of Italy and for his measured manners. Another nickname he has been given is "Il principe rosso" ("The red prince"), with "red" alluding to communism.

Notes

- ^ a b Napolitano, Giorgio (2005). Dal Pci al socialismo europeo. Un'autobiografia politica (in Italian). Laterza. ISBN 88-420-7715-1.

- ^ Graziani, Nicola. "Quirinale: Giorgio Napolitano, il compagno gentiluomo" (in Italian). Retrieved 2006-05-13.

- ^ a b Quirinale.it. "Biography". Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ^ Camera.it. "Il Presidente Giorgio Napolitano" (in Italian). Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ^ Corriere della Sera. "«Principe rosso», violò il tabù del Viminale" (in Italian). Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ^ CNN. "Italy finally agrees on president". Retrieved 2006-05-13.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ La Repubblica. "Da Berlusconi auguri con freddezza. Calderoli: "Non lo riconosciamo"" (in Italian). Retrieved 2006-05-16.

- ^ Il Giornale. "Sul colle sventola bandiera rossa" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 2006-05-14.

- ^ International Herald Tribune. "Italy's president pays tribute in Hungary to 1956 revolution". Retrieved 2006-10-06.

- ^ http://www.unita.it/view.asp?IDcontent=63512

- ^ [1], [2]

- ^ "Italian PM hands in resignation". BBC News. 2007-02-21. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Italian PM asked to resume duties". BBC News. 2007-02-24. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Italian PM survives Senate vote". BBC News. 2007-02-28. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Italian PM survives House vote". CNN News. 2007-02-28. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ La Repubblica. "Governo, Napolitano annuncia "Martedì inizio le consultazioni"" (in Italian). Retrieved 2006-05-13.

External links

- BBC News. "Napolitano elected Italy's leader". Retrieved 2006-05-10.

- Articles with trivia sections from June 2007

- Presidents of the Italian Republic

- Presidents of the Italian Chamber of Deputies

- Current national leaders

- Democratic Party of the Left and Democrats of the Left Party members

- Italian Life Senators

- Italian Ministers of the Interior

- Members of the Italian Communist Party

- Italian people of World War II

- 1925 births

- Living people