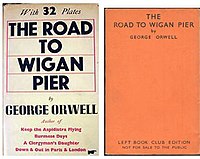

The Road to Wigan Pier

| |

| Author | George Orwell |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Autobiography |

| Publisher | Victor Gollancz (London) |

Publication date | 8 March 1937 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (Hardback) |

| ISBN | ISBN Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

The Road to Wigan Pier was written by George Orwell and published in 1937. It is a sociological analysis of living conditions in the industrial north of England before World War II that was commissioned by the Left Book Club in January 1936. Orwell received a £500 advance - two years' income for him at the time - and spent the period from 31 January to 30 March 1936 living in Barnsley, Sheffield and Wigan researching the book.[1]

The book is divided into two sections.

Part One

George Orwell set out to report on working class life in the bleak industrial heartlands of the West Midlands, Yorkshire and Lancashire. Orwell spent a considerable time living among the people and as such his descriptions are detailed and vivid.

Chapter One describes the life of the Brooker Family, a more wealthy example of the northern working class. They have a shop and cheap lodging house in their home. Orwell describes the old people who live in the home and their living conditions.

Chapter Two describes the life of miners and conditions down a coal mine. Orwell describes how he went down a coal mine to observe proceedings and he explains how the coal is distributed. The working conditions are very poor. This is the part of the book most often quoted.

Chapter Three describes the social situation of the average miner. Hygienic and financial conditions are discussed. Orwell explains why most miners do not actually earn as much as they are sometimes believed to.

Chapter Four describes the housing situation in the industrial north. There is a housing shortage in the region and therefore people are more likely to accept substandard housing. The housing conditions are very poor.

Chapter Five explores unemployment and Orwell explains that the unemployment statistics of the time are misleading.

Chapter Six deals with the food of the average miner and how, although they generally have enough money to buy food, most families prefer to buy something tasty to enrich their dull lives. This leads to malnutrition and physical degeneration in many families.

Chapter Seven describes the ugliness of the industrial towns in the north of England.

Part Two

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (December 2007) |

In contrast to the straightforward documentary of the first part of the book, in part two Orwell discusses the relevance of socialism to improving living conditions. This section proved controversial.

Orwell sets out his initial premises very simply

- Are the appalling conditions described in part 1 tolerable? (No)

- Is socialism “wholeheartedly applied as a world system” capable of improving those conditions? (Yes)

- Why then are we not all socialists?

The rest of the book consists of Orwell’s attempt to answer this difficult question. He points out that most people who argue against socialism do not do so because of straightforward selfish motives, or because they do not believe that the system would work, but for more complex emotional reasons, which (according to Orwell) most socialists misunderstand. He identifies 5 main problems.

- Class prejudice. This is real and it is visceral. Middle class socialists do themselves no favours by pretending it does not exist and - by glorifying the manual worker - they tend to alienate that large section of the population which is economically working class but culturally middle class.

- Machine worship. Orwell finds most socialists guilty of this. Orwell himself is suspicious of technological progress for its own sake and thinks it inevitably leads to softness and decadence. He points out that most fictional technically advanced socialist utopias are deadly dull. H.G. Wells in particular is criticised on these grounds.

- Crankiness. Amongst many other types of people Orwell specifies people who have beards or wear sandals, vegetarians, and nudists as contributing to socialism's negative reputation among many more conventional people.

- Turgid language. Those who pepper their sentences with “notwithstandings” and “heretofores” and become over excited when discussing dialectical materialism are unlikely to gain much popular support.

- Failure to concentrate on the basics. Socialism should be about common decency and fair shares for all rather than political orthodoxy or philosophical consistency.

In presenting these arguments Orwell takes on the role of devil's advocate. He states very plainly that he himself is in favour of socialism but feels it necessary to point out reasons why many people, who would benefit from socialism, and should logically support it, are in practice likely to be strong opponents. It is perhaps unfortunate that Orwell’s language in these passages is so lively and amusing that people tend to remember these parts of the book and forget its overall message. In short Orwell plays the devil's advocate but he also gives the devil all the best tunes.

Orwell’s publisher, Victor Gollancz, was so concerned that these passages would be misinterpreted, and that the (mostly middle class) members of the Left Book Club would be upset and write him complaining letters, that he added a foreword in which he raises some caveats about Orwell's claims in Part Two. He suggests, for instance, that Orwell may exaggerate the visceral contempt that the English middle classes hold for the working class, adding, however, that, "I may be a bad judge of the question,, for I am a Jew, and passed the years of my early boyhood in a fairly close Jewish community; and, among Jews of this type, class distinctions do not exist." Other concerns Gollancz raises are that Orwell should so instinctively dismiss movements such as pacifism or feminism as incompatible with or counter-productive to the Socialist cause, and that Orwell relies too much upon a poorly defined, emotional concept of Socialism. Gollancz's claim that Orwell "does not once define what he means by Socialism" in The Road to Wigan Pier is indeed difficult to refute. The foreword does not appear in some modern editions of the book, though it was included, for instance, in Harcourt Brace Jovanovich's first American edition in the 1950s.

At a later date Gollancz published part 1 on its own, against Orwell’s wishes, and he refused to publish “Homage to Catalonia” at all.

Quotes

“A middle class child is taught simultaneously to wash his neck, to be ready to die for his country, and to despise the working classes”

“The ordinary man may not flinch from a dictatorship of the proletariat, if you offer it tactfully; offer him a dictatorship of the prigs and he gets ready to fight”

“that dreary tribe of high–minded women and sandal-wearers and bearded fruit juice drinkers who come flocking to the scent of “progress” like bluebottles to a dead cat”

“the food-crank is by definition a person willing to cut himself off from ordinary human society in hopes of adding five years on to the life of his carcase; that is, a person out of touch with common humanity”

“The logical end of machine civilization is to reduce the human being to something resembling a brain in a bottle. That is the goal towards which we are already moving, though, of course, we have no intention of getting there; just as a man who drinks a bottle of whisky a day does not actually intend to get cirrhosis of the liver.”

“If only the sandals and the pistachio-coloured shirts could be put in a pile and burnt, and every vegetarian, teetotaller, and creeping Jesus sent home to Welwyn Garden City to do his yoga exercises quietly!”

“(The impoverished middle class) may sink without further struggles into the working classes where we belong, and probably when we get there it will not be so dreadful as we feared, for, after all, we have nothing to lose but our aitches”

Misquatations

Quotations wrongly attributed to George Orwell have appeared in buildings around Manchester. In Urbis, the entrance to the lift reads "Manchester, the belly and guts of the nation" and is cited as George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier. This line does not appear in the book and is unlikely that he wrote the words at all. Yet, the exact quotation also appears on the ground floor wall of The City Tower near Piccadilly Gardens.

Name of the Book

The name of the book comes from a music hall routine by a British comedian. Although a pier is a structure built out into the water from the shore, in Britain the term has the connotation of a seaside holiday. Wigan was a small grimy mill town on a canal accessed by boats via an offloading structure, although it primarily used land transport. Hence the music hall joke of a mill town with its own seaside resort, and Orwell's choice of title implied his belief that socialism could improve life to an unprecedented degree even in a mill town.

Orwell also mentions that Wigan did not actually have a pier because it collapsed some years before he visited.

All that remains of Wigan Pier is a section of raised railway track.

References:

"The Road to Wigan Pier" by George Orwell with a preface by Victor Gollancz Pub Victor Gollancz ltd. 1937

"George Orwell a Life" by Bernard Crick Pub Penguin 1980

- ^ Bernard Crick, ‘Blair, Eric Arthur [George Orwell] (1903–1950)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004)

External links

- The Road to Wigan Pier - Searchable, indexed etext.

- The Road to Wigan Pier Complete book with publication data and search feature.

- Orwell answers a question about Wigan Pier Excerpt from a broadcast of the BBC's Overseas Service.