Dvorak keyboard layout

The Dvorak Simplified Keyboard (pronounced /ˈdvoɹæk/) is a keyboard layout patented in 1936 by Dr. August Dvorak, an educational psychologist and professor of education[1] at the University of Washington in Seattle,[2] and William Dealey as an alternative to the more common QWERTY layout. It has also been called the Simplified Keyboard or American Simplified Keyboard, but is commonly known as the Dvorak keyboard or Dvorak layout.

Although the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard ("DSK") has so far failed to displace the QWERTY standard, it has seen an increase in popularity in recent years especially among computer programmers and others whose jobs require them to do extensive amounts of typing.[citation needed] It has become easier to access in the computer age, being included with all major operating systems (such as Mac OS X, Microsoft Windows, Linux and BSD) in addition to the standard QWERTY layout. It is also supported at the hardware level by some high-end ergonomic keyboards.

I do not know what to present for Christmas to the girl .... Help me please

Original Dvorak layout

The layout standardized by the ANSI differs from the original or "classic" layout devised by Dvorak. Today’s keyboards have more keys than the original typewriter did, and other significant differences existed:

- The numeric keys of the classic Dvorak layout are as follows:

7 5 3 1 9 0 2 4 6 8 |

- In the classic Dvorak layout, the question mark key [?] is in the leftmost position of the upper row, while the slash mark key [/] is in the rightmost position of the upper row.

- The following symbols share keys (the second symbol being printed when the SHIFT key is pressed):

- colon [:] and question mark [?]

- ampersand [&] and slash [/]

- comma [,] and semicolon [;]

Modern U.S. keyboard layouts almost always place semicolon and colon together on a single key and slash and question mark together on a single key.[3] Thus, if the keycaps of a modern keyboard are rearranged so that the unshifted symbol characters match the classic Dvorak layout then, sensibly, the result is the ANSI layout.

Modern operating systems

Windows

According to Microsoft, versions of the Windows operating system including Windows 95, Windows NT 3.51 and higher have shipped with support for the U.S. Dvorak layout.[4] Free updates to use the layout on earlier Windows versions are available for download from Microsoft.

Unix-based systems

Many operating systems based on UNIX, including OpenBSD, FreeBSD, Plan 9, and most Linux distributions, can be configured to use either the U.S. Dvorak layout or the UK/British Dvorak Layout. However, all current Unix-like systems with Xorg and appropriate keymaps installed (and virtually all systems meant for desktop use include them) are able to use any QWERTY layout as a Dvorak one without any problems nor additional configuration. This removes the burden of producing additional keymaps for every variant of QWERTY provided.

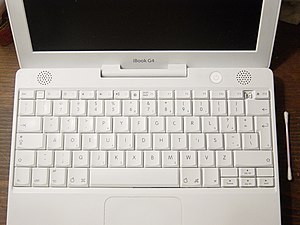

Mac OS X

Apple had Dvorak partisans since the company’s early (pre-IPO) days. The Apple III used a keyboard-layout file loaded from a floppy disk: the standard system-software package included QWERTY and Dvorak layout files. Changing layouts required restarting the machine. The Apple IIe had a keyboard ROM that translated keystrokes into characters. The ROM contained both QWERTY and Dvorak layouts, but the QWERTY layout was enabled by default. A modification could be made by pulling out the ROM, bending up four pins, soldering a resistor between two pins, soldering two others to a pair of wires connected to a micro switch, which was installed in a pre-existing hole in the back of the machine, then plugging the modified ROM back in its socket. The "hack" was reversible and did no damage. By flipping a switch on the machine’s back panel, the user could switch from one layout to the other. This modification was entirely unofficial but was inadvertently demonstrated at the 1984 Comdex show, in Las Vegas, by an Apple employee whose mission was to demonstrate Apple Logo II. The employee had become accustomed to the Dvorak layout and brought the necessary parts to the show, installed them in a demo machine, then did his Logo demo. Viewers noticed that he always reached behind the machine before and after allowing other people to type and asked him about the modification. He spent as much time explaining the Dvorak keyboard as explaining Logo.

Apple brought new interest to the Dvorak layout with the Apple IIc, which had a mechanical switch above the keyboard whereby the user could switch back and forth between the QWERTY layout and the ANSI Dvorak layout: this was the most official version of the IIe Dvorak mod. Late-model Apple IIe computers added a switch inside the computer for switching to Dvorak, and the Dvorak layout was also selectable using the built-in control panel applet on the Apple IIGS.

It is generally believed that the Apple Lisa never had a Dvorak-layout option. Keyboard-mapping on the Lisa was understood by few among the Lisa wizards and was never documented anywhere.

In its early days, the Macintosh could be converted to the Dvorak layout by making changes to the "System" file: this was not easily reversible and required restarting the machine. This modification was highly unofficial, but it was comparable to many other user-modifications and customizations that Mac users made. Using the legendary "resource editor", ResEdit, users could create keyboard layouts, icons, and other useful items. Many wonders appeared at user-group meetings. A few years later, a third-party developer offered a utility program called MacKeymeleon, which put a menu on the menu bar that allowed on-the-fly switching of keyboard layouts. Eventually, Apple Macintosh engineers built the functionality of this utility into the standard System Software, along with a few layouts:QWERTY, Dvorak, French (AZERTY), and other foreign-language layouts.

Since about 1998, beginning with Mac OS 8.6, Apple has included the Dvorak layout. Apple also includes a Dvorak variant they call “Dvorak - Qwerty Command”. With this layout, the keyboard becomes QWERTY when the Command (Apple) key is held down. This makes transition for some people easier. Mac OS and subsequently Mac OS X allows "on-the-fly" switching between layouts: a menu-bar icon (by default, a national flag that matches the current language) brings up a popup menu, allowing the user to choose the desired layout. Subsequent keystrokes will reflect the choice, which can be reversed the same way.

Criticism

Although the Dvorak layout is the only other keyboard layout registered with ANSI and is provided with all major operating systems, attempts to convert universally to the Dvorak layout have not succeeded. The failure of the Dvorak layout to displace the QWERTY layout has been the subject of some studies and of considerable debate.[5][6][7] However, in considering resistance to the adoption of the Dvorak layout, different segments of the market (non-typists, typists, corporations and manufacturers) differ in the extent, nature, and motivation of their resistance. Furthermore, the influence of these factors on the different segments of the market has changed over time, following changes in technology and awareness of Dvorak as an alternative keyboard layout. Factors against adoption of the Dvorak layout have included the following:[citation needed]

- Failure to demonstrate superiority in speed, economy of effort, and accuracy--noting that the significant issue here is the demonstrability. Few studies have been done on the relative efficiency of the two keyboard layouts, and those studies have been criticised for failing to adhere to rigorous academic standards.

- Failure to achieve the general population's awareness that the Dvorak layout existed. This improved somewhat following the Guinness Book of Records' 1985 publication of Barbara Blackburn’s achievement of 212 wpm using a Dvorak keyboard[citation needed], and again in the mid-1990s when computer operating systems began to incorporate the Dvorak layout as an option[citation needed].

- Failure to overcome an investment in competence in the QWERTY layout made by a large number of typists and typist trainers prior to the general availability of the Dvorak layout. This investment has proved the most powerful influence up until the 1990s. Typing training in schools and secretarial colleges is almost always done on the QWERTY layout both because it conforms with the expectation of industry and because it is the layout with which most teachers or trainers are already familiar. Many QWERTY typists have retrained themselves to use the Dvorak layout because the emphasis in touch typing is traditionally on speed and accuracy, and because Dvorak users commonly report a reduction in typing-related injuries such as carpal-tunnel syndrome.

- A reduction in efficiency while learning the Dvorak layout further impedes its adoption by typists already competent with QWERTY, and the organizations that employ them---although it has been claimed that [weasel words] on average, typists who switch to Dvorak require just two to three weeks' use to surpass their former typing speeds.[citation needed]

- Failure to persuade large typewriter manufacturers to produce significant volumes of typewriters equipped with Dvorak layouts. It would be sufficient to argue that the manufacturers were responding to the large QWERTY user base, rather than considering the plausible but unproven assertion that manufacturers had a vested interest in ensuring that typists could not type faster than the machines could respond mechanically.

- Converting standard mechanical typewriters to Dvorak (or any alternative, e.g. international, layout) was often impractical, and at best expensive, so switching to Dvorak usually required a new, dedicated machine. A notable exception was the popular IBM Selectric typewriter, which used a single spherical typing element rather than individual character hammers; it could easily be converted by replacing the QWERTY typing element with an available Dvorak equivalent.

The advent of PCs created the opportunity to use computer programs to change the character that was produced when a particular key was pressed. This capacity benefited not only Dvorak typists, but those who typed in languages other than English. With early computers, this required the contents of the character-generator ROM to be changed; but with subsequent designs, only a table in memory or the disk file storing this table needed to be changed. By the mid 1990s the Dvorak layout was a standard option on most computer systems. With most modern operating systems, it is possible to switch keyboard layouts "on the fly" without additional software or reconfiguration. This makes it very easy for users of different key layouts to share a PC.

Like all touch typists, Dvorak touch typists do not need to look at their keyboards, enabling them to use PCs in Dvorak mode without physically modifying keyboards manufactured for and marked with the QWERTY layout. Other Dvorak typists prefer to modify their keyboards to show the Dvorak layout, or to obtain dedicated Dvorak keyboards.

- Incompatibility between the two keyboard layouts on computers, where keys are assigned additional functions within software programs. In some cases related additional functions are assigned to keys that are physically proximate on the QWERTY layout, but not so in the Dvorak layout; for example, the Unix text editor vi uses the keys H, J, K and L to cause movement to the left, down, up, and right, respectively. With a QWERTY layout, these keys are all together under the right-hand home row, but with the Dvorak layout they are no longer neatly together. In many video games, keys W, A, S and D are used for arrow movements (their inverse-T arrangement on a QWERTY layout mirrors the arrangement of the cursor keys). In the Dvorak layout, this is no longer true. Keyboard shortcuts in GUIs for undo, cut, copy and paste operations are Ctrl (or Command) + Z, X, C, and V respectively; conveniently located in the same row in the QWERTY layout, but not on a Dvorak layout. Some of these issues can be overcome with programming solutions, but it adds a layer of complexity to using some computer applications with the Dvorak layout. The Mac OS offers an elegant solution: two Dvorak keyboard layouts are available on the Keyboard menu. The first, called simply Dvorak, remaps all the characters produced by a key (with and without modifier keys) from the old QWERTY key to the new Dvorak key. The second, called Dvorak QWERTY-Command remaps all the characters produced by the key-and-modifier combinations--except those in which the Command key is pressed] to the new Dvorak key; the Command-key variants are left the same as in the QWERTY layout. A curious and patient user can puzzle this out by using the Keyboard Viewer (Mac OS X) or the Keyboard desk accessory (older versions)).

- Some confusion regarding which of the keyboard layouts designed by August Dvorak is the "real" Dvorak layout. This arose in part due to the existence of, in addition to the standard layout, layouts for left-handed (only) and right-handed (only) use. Also, while Dvorak specified a particular layout for the number sequence at the top of the keyboard, most implementations of the Dvorak layout retain the ‘1,2,3...9,0’ arrangement: most people who want to type numbers quickly will use the numeric keypad rather than the top row.

An appreciation of the strength of the resistance factors (particularly the investment in typewriter manufacturing) suggests that the Dvorak layout would need to have been significantly superior to the QWERTY layout in order for the former to displace the latter in widespread use in the past. If the Dvorak layout is inherently at least as efficient as, or more efficient than, the QWERTY layout, then one might expect to see an increasing rate of use as resistance factors (such as lack of awareness, non-programmable machines, and one-style formal training) become less powerful. There are no surveys or studies looking at the rate of use of the Dvorak layout over time.

A discussion of the Dvorak layout is sometimes used as an exercise by management consultants to illustrate the difficulties of change. The Dvorak layout is often used as a standard example of network effects, particularly in economics textbooks, the other standard example being the competition between Betamax and VHS. These examples are used to demonstrate that inferior technologies sometimes succeed simply because they become customary, even though the Dvorak layout's superiority is not clearly established.[1]

One-handed versions

There are also Dvorak arrangements designed for one-handed typing, which can provide increased accessibility for those who have difficulty with typical keyboards. Other users enjoy the ability to simultaneously type and control a mouse. Separate arrangements have been designed for each hand. Note that the hand is intended to rest near the center of the keyboard, making these layouts impractical to use with split ergonomic keyboards.

The layouts depicted above are available under Microsoft Windows. There is another layout that is slightly different, where the numbers form three columns.

Programmer Dvorak

Programmer Dvorak is a Keyboard Layout developed by Electronics engineer Roland Kaufmann and targeted towards people writing source code for C, Java, Pascal, LISP, CSS and XML.[8] The layout is based on the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard, with several enhancements intended to make typing easier for programmers.

While the alphabetic keys are placed as on the original Dvorak layout, most of the others are changed. The most noticeable difference is that the top row is devoted to brackets and other operational characters, and the numbers must be accessed using the shift key. Also, differing from most Dvorak implementations but following August Dvorak’s original design, the numbers are not placed in ascending order.

Other languages

Although DSK is implemented in many other languages other than English, there is a possible issue about it. Every Dvorak implementation in other languages leave the Roman characters in the same position as the English DSK. However, other (occidental) language grammars can clearly have other typing needs for optimization (many very different than English). This raises a point which questions Dvorak Simplified Keyboard’s typing optimizations as language free, and can be another possible cause of Dvorak not replacing QWERTY worldwide.

An implementation for Swedish, known as Svorak [2], places the three extra Swedish vowels (å, ä and ö) on the leftmost three keys of the upper row, which correspond to punctuation symbols on the English Dvorak layout. These punctuation symbols are then juggled with other keys, and the Alt-Gr key is required to access some of them.

Another Swedish version, Svdvorak by Gunnar Parment, keeps the punctuation symbols as they were in the English version; the first extra vowel (å) is placed in the far left of the top row while the other two (ä and ö) are placed at the far left of the bottom row.

The Swedish variant that most closely resembles the American Dvorak layout is Thomas Lundqvist’s sv_dvorak, which places å, ä and ö like Parment’s layout, but keeps the American placement of most special characters.

The Norwegian implementation (known as "Norsk Dvorak") is similar to Parment’s layout, with "æ" and "ø" replacing "ä" and "ö".

The Danish layout DanskDvorak [3] is similar to the Norwegian.

A Finnish DAS keyboard layout [4] follows many of Dvorak’s design principles, but the layout is an original design based on the most common letters and letter combinations in the Finnish language. Matti Airas has also made another layout for Finnish [5]. Finnish can also be typed reasonably well with the English Dvorak layout if the letters ä and ö are added.

Turkish F keyboard layout (link) is also an original design with Dvorak's design principles, however it's not clear if it is inspired by Dvorak or not. Turkish F keyboard was standardized in 1955 and the layout has been a requirement for imported typewriters since 1963.

There are some non standard Brazilian Dvorak keyboard layouts currently in development. The simpler design (also called BRDK) is just a Dvorak layout plus some keys from the Brazilian ABNT2 keyboard layout. Another design, however, was specifically designed for writing Brazilian Portuguese, by means of a study that optimized typing statistics, like frequent letters, trigraphs and words.[9]

The most common German Dvorak layout is the German Type II layout. It is available for Windows, Linux, and Mac OS X. There is also the NEO layout [6] and the de ergo layout [7], both original layouts that also follow many of Dvorak’s design principles.

There are also French [8] or [9] and Spanish [10] layouts, and also a proposed Esperanto version.

A Hellenic version of the Dvorak layout was released on Valentine’s Day 2007. This layout, unlike other Hellenic Dvorak layouts, preserves the spirit of Dvorak wherein the vowel keys are all placed on the left side of the keyboard. Currently this version is for Mac OS X [11]

United Kingdom (British) layouts

Whether Dvorak or QWERTY, a United Kingdom (British) keyboard differs from the US equivalent in these ways: the " and @ are swapped; the backslash/pipe [\ |] key is in an extra position (to the right of the lower left shift key); there is a taller return/enter key which places the hash/tilde [# ~] key to its lower left corner (see picture).

All these variations apply to the Simplified Dvorak and Dvorak for the Left Hand and Right Hand varieties.

The most notable difference between the US and UK Dvorak layout is because the [2 "] key has to remain on the top row. This means that the query [/ ?] key retains its classic Dvorak location, top left, albeit shifted. Arguably, interchanging the [/ ?] and [' @] keys more closely matches the US layout, and the use of "@" has increased in the information technology age.

Other United Kingdom (British) Dvorak layouts exist, either leaving all the symbol keys in the standard United Kingdom locations (that is, the numeral keys and the block of four symbol keys: "[ {", "] }", "- _", "= +" don't move) or not moving the numbers.

Notable users

- Barbara Blackburn, world typing speed record holder[10]

- Bram Cohen, inventor of Bittorrent[11]

- Matt Mullenweg, lead developer of WordPress[12]

- Terry Goodkind, author of The Sword of Truth[13]

- Piers Anthony, author of the Xanth novels, often wrote in the 1980s author's notes in the books about how his Dvorak use prevented him from converting to a word processor. This was made even more difficult because he uses an alternate Dvorak layout (swapping the hyphen and apostrophe keys - the apostrophe key on his keyboard is where it is on a standard US keyboard).

See also

- Keyboard layout

- QWERTY

- Touch typing

- Velotype

- Maltron keyboard

- Repetitive strain injury

- Path dependence

References

- ^ Cassingham, Randy C. (1986). The Dvorak Keyboard. Freelance Communications. pp. p. 32. ISBN 0935309101.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|link=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dvorak, August et al. (1936). Typewriting Behavior. American Book Company. Title page.

- ^ "Modern US keyboard". Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- ^ Microsoft.com: Alternative Keyboard Layouts

- ^

David, Paul A. (1985). "Clio and the Economics of QWERTY". American Economic Review. 75: 332–37.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) and David, Paul A. (1986). "Understanding the Economics of QWERTY: The Necessity of History.". In W. N Parker. (ed.). Economic History and the Modern Economist. New York: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0631147993.. - ^

Liebowitz, Stan J. (1990). "The Fable of the Keys". Journal of Law & Economics. 33 (1): 1–25. ISSN 0022-2186. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

We show that David's version of the history of the market's rejection of Dvorak does not report the true history, and we present evidence that the continued use of Qwerty is efficient given the current understanding of keyboard design.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

Brooks, Marcus W. (April 5 1999). "The Fable of the Fable". Retrieved 2007-09-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|originaldate=ignored (help) a pro-Dvorak rebuttal of Liebowitz & Margolis - ^ Kaufmann, Roland. "Programmer Dvorak Keyboard Layout". Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ "O que é o teclado brasileiro?". Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ^ "Barbara Blackburn, the World's Fastest Typist". Retrieved 2007-03-08.

- ^

Cohen, Bram (March 7, 2006). "Keyboard Switching". Retrieved 2007-06-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

Mullenweg, Matt (August 31, 2003). "On the Dvorak Keyboard Layout". Retrieved 2007-06-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

"Terry Goodkind - Interviews and Past Chats". Retrieved 2007-08-20.

I type on a devork keyboard layout...

External links

- DvZine.org - A print and webcomic zine advocating the Dvorak Keyboard and teaching its history.

- A Basic Course in Dvorak - by Dan Wood

- Dvorak vs QWERTY Tool - Comparison site that allows to calculate statistics of the different layout.