Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2008 January 7

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < January 6 | << Dec | January | Feb >> | January 8 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

January 7

Parasites

How do they survive inside bodies? 138.217.145.45 (talk) 08:29, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Lots of different ways, but generally by attaching to tissue (sometimes under the skin, in the gut or the bloodstream) and getting the nutrients they need to survive from the host. Ones that live inside bodies are called endoparasites. An example is hookworm, which live in the small intestine and suck blood to survive. Rockpocket 09:14, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- I should note that many intestinal worms are fully capable of surviving stomach acid. Their eggs especially. 64.236.121.129 (talk) 18:56, 11 January 2008 (UTC)

Sun

Is the Sun part of any constelation? 138.217.145.45 (talk) 11:50, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- No. See List of constellations. --Sean 12:51, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Strictly speaking, the sun might be part of a constellation for a civilisation living on another planet, orbiting another star in a solar system different from ours. However, at this point it's mere speculation, as we haven't contacted them yet in this or any other matter. --Ouro (blah blah) 13:05, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Constellations do not necessarily consist of stars that are relatively close together: they have significance to us because of the 'shapes' they make in the night sky. To observers on a planet in another part of the galaxy there might be no apparent pattern at all; indeed it might never be possible to see all the stars of Orion, say, at the same time from any point on the surface of the planet. AndrewWTaylor (talk) 13:19, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- That's right. By definition, constellations can only consist of fixed stars.--Shantavira|feed me 15:11, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

Another question- how close to our solar system would another species have to be to be able to see our sun without a telescope? 70.162.25.53 (talk) 02:56, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- By "another species", do you mean "another species that just happens to have eyesight identical to human beings, on a planet whose atmospheric transmission and night-sky brightness are identical to a dark site on earth"? If so, we can subtract the sun's absolute magnitude of 4.83 from the faintest apparent magnitude these "aliens" can see of 6.5, for a distance modulus of 1.67. That works out to a distance of about 21.5 parsecs. Call it 20 pc in round numbers. -- Coneslayer (talk) 03:17, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

K shell

hello, I wanted t ask that why do we name the first shell of quantum atom model,"K" (principal quantum number 1)? max6 —Preceding unsigned comment added by Max6 (talk • contribs) 12:38, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Electron shell says Barkla labelled them with the letters K, L, M, etc. The origin of this terminology was alphabetic, so it sounds like he just started at K arbitrarily. --Sean 12:55, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- It suggests to me that he thought there might end up being more shells before K, and he wanted to leave a lot of room (which is a rather modest thing to do). But I don't know—often such details in the history of physics are not easy to document because after getting repeated 50 times over it is hard to find out what the so-called "seminal paper" was that launched it, because the scientists themselves often just repeat such things without referencing the original. (In some rare cases this is true and the original is consulted for many years—like Einstein's 1905 papers—but in most cases, especially with experimental physics, this is not so, and just results get reported.) --24.147.86.187 (talk) 01:36, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

Science

What is the best method, other then heat, to melt ice????????? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 72.186.80.145 (talk) 15:12, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- You can't melt ice without heat. The physical process of melting requires that the ice be absorbing heat. Someguy1221 (talk) 15:51, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Well, you could add something to the ice that lowers its freezing point. This is why they salt the roads in the winter in many places, for example. Friday (talk) 15:53, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- OK, unless you're cheating like that :-p Someguy1221 (talk) 16:00, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Doesn't that still involve some heat? Or can salt be dissolved and absorbed by solid ice? APL (talk) 16:10, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- The mechanism by which salt lowers the freezing point is that water molecules at the solid/liquid interface are constantly moving from one state to the other, but when you add salt, water in the liquid state attaches to it and is then unable to move back to the solid part. Therefore, I imagine that you would need at least some amount of water on the ice's surface to allow salt to melt it. --Sean 17:54, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- But by your own argument, there's always some amount of water at the surface, so it always works (as long as the temperature's not lower than that of salt water, of course). —Steve Summit (talk) 22:59, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- The mechanism by which salt lowers the freezing point is that water molecules at the solid/liquid interface are constantly moving from one state to the other, but when you add salt, water in the liquid state attaches to it and is then unable to move back to the solid part. Therefore, I imagine that you would need at least some amount of water on the ice's surface to allow salt to melt it. --Sean 17:54, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Doesn't that still involve some heat? Or can salt be dissolved and absorbed by solid ice? APL (talk) 16:10, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- OK, unless you're cheating like that :-p Someguy1221 (talk) 16:00, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- I know you can boil ice by putting it in a vacuum chamber, so you can probably melt it by controlling the pressure more carefully. Black Carrot (talk) 16:52, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Unexpectedly, you can melt ice by increasing pressure - see regelation. Gandalf61 (talk) 16:55, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Yeah, that's supposedly what makes skating possible, though there's no mention of it at the article on regelation. --Trovatore (talk) 23:06, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- With good reason: that's a myth. See under Ice skating#How it works, last paragraph in the section. --Anonymous, 03:48 UTC, January 8, 2008.

- Extreme pressure ends up heating things, just think of those pressed penny machines (or Elongated_coin. Unless that counts as heat. --Omnipotence407 (talk) 03:32, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- It's not the pressure causing the heat, but the friction from compression itself. Someguy1221 (talk) 19:23, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

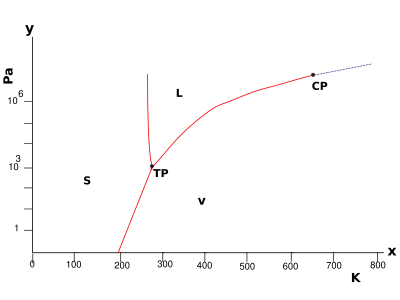

- I'm sure there's a phase diagram of water somewhere to demonstrate why this is, but you can't turn ice into water by reducing the pressure: it will sublimate to water vapor instead. --67.185.172.158 (talk) 10:23, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- Found it. It was on water (molecule). You appear to be correct. Of course, if you increase the pressure to where it melts and keep increasing it until it solidifies as another form of ice, then decreasing the pressure will melt it. — Daniel 23:51, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

Question on salt and excercise

What happends if you take in a large ammount of salt and then do training? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Bastard Soap (talk • contribs) 15:21, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- We're not well equipped to give medical or training advice. All I would recommend is, don't go trying to exceed the recommended intake of salt unless directed by a medical professional. See also Salt#Health_effects for the relevant section of our article. Friday (talk) 15:51, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

Cells

Plant cells have cell walls but animal cells do not. Why do animal cells not hav cell walls? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Stylin99 (talk • contribs) 15:44, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Cell walls are quite rigid, which wouldn't be beneficial for anything that planned on moving a lot. Instead, those animals that actually needed the rigidness they lacked by not having cell walls evolved various forms of skeletons and exoskeletons. For the purpose of an animal, these are atually superior, as they afford rigidness where such is needed, and allow the rest of the organism to remain flexible. Someguy1221 (talk) 15:57, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

Microscope

1.Who is the first person that invented microscope and when it is invented? Can anyone tell me more about Anton van Leeuwenhoek's microscope and Roberts Hooke's microscope? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Stylin99 (talk • contribs) 15:51, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- The article about microscope may help you here. It doesn't look long in history, but it at least mentions Hooke's version. His own article has a bit more. Friday (talk) 15:59, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- We do have a Timeline of microscope technology, and the bulk of the history appears in the Optical microscope article. Someguy1221 (talk) 16:01, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- I have added a little more at Wikipedia:Reference_desk/Miscellaneous#Microscope. By the way, it's a good idea to ask a question on only one desk - that way, the answers can all be in the same place, which is easier for everyone to follow. DuncanHill (talk) 16:02, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

why does a comet leave atrail behind it?

why does a comet leave a trail behind it? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 195.229.236.212 (talk) 16:35, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- You may want to read our comet article and if this doesn't answer your questions, come back here again.

- Atlant (talk) 16:37, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Are you referring to a comet's tail? That's not exactly its trail. --Ouro (blah blah) 16:58, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- (longer answer without pun) A comet will leave a trail (its tail aside for now) because it could shed its material, primarily rock and ice because that's what they're composed of, or other material (like hydrogen or water) that it would expel by means of jets which some comets possess. Should the comet not be caught in a stream of solar, interstellar or other type of cosmic wind, the trail would be pointing in the opposite to the direction it's travelling in. The tail, now, could be a type of trail that's not pointed this way but away from the source of the wind it's caught in (the simplest and easiest example to observe would be a comet passing by the Sun with its tail pointing away from it). Right? --Ouro (blah blah) 17:08, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- If the comet sheds rocks they don't just stay were the comet was when they were shed, but they continue to orbit the sun (due to their inertia). The orbits of the fragments would be slightly different from the comet's orbit. After many orbital periods, the rocks will be distributed along the comet's orbit, and we will see meteor showers if Earth passes the comet's orbit. Icek (talk) 06:17, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- As a result of space missions such as Giotto and Stardust we actually know quite a lot about the composition of comet tails. The particles in the tail of Comet Halley, as observed by Gitto, had an average size similar to cigarette smoke particles. Stardust collected about a million particles from the coma of Comet Wild 2, of which only 10 were larger than 0.1mm in size. Comets do sometimes break apart into large "rocks" (Comet Ikeya-Seki for example), but if these pieces are too large to be affected by the solar wind then they do indeed continue in almost identical orbits to the original comet. Gandalf61 (talk) 11:26, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

Falling from an aircraft into the sea

In a James Bond film the hero falls from an aircraft without a parachute. This made me wonder: 1) What is the greatest height you could fall into the deep sea from, and survive? 2) Not really a science question, but has anyone ever been suicidally crazy enough to leap from a plane without a parachute, and be handed and put on a parachute from another skydiver in mid-air? Thanks. 80.0.105.180 (talk) 19:36, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Multiple people have survived jumps off the Golden Gate Bridge. So, you have to go higher than 746 feet. I'm not sure how many popular jumping spots there are that are higher than that. -- kainaw™ 19:58, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- From watching MythBusters, it seems to be completely dependent on multiple factors, including density of the water, entry, velocity, etc. But as Kainaw said, people have survived jumps of the Golden Gate Bridge. So it would depend on the height of the plane as well. I recall something about a person surviving a mile-high fall from a plane on land...I'll research that and repost. EWHS (talk) 20:04, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Checking parachuting, a common parachuting height is 13,000 feet. That is much higher than 746 feet. Of course, there is a point at which you'll reach terminal velocity and it won't matter how much higher you are when you jump. I don't know what that altitude is. -- kainaw™ 20:09, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- According to terminal velocity the max speed that a person would hit the water in the safest manner (feet first, arms crossed tight, and head back) is 200mph. So, this becomes a question of water density. How dense can the water be to survive a 200mph impact? -- kainaw™ 20:12, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- According to this, you can survive a 10560 feet (2 mile) fall over land. EWHS (talk) 20:17, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Further research indicates that he had at least some parachute functionality. Nimur (talk) 01:16, 9 January 2008 (UTC)

- There's a pretty important difference between what is typically non-fatal, versus what someone might occasionally survive by extraordinary luck. Friday (talk) 20:41, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- According to this, you can survive a 10560 feet (2 mile) fall over land. EWHS (talk) 20:17, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- So, the question should be rephrased: what altitude yields an LD50 for many jumpers without parachutes? Nimur (talk) 01:12, 9 January 2008 (UTC)

- A quick note on the Golden Gate: 746 ft isn't really the metric most commonly associated (that's height from the top of the tower). Rather, most jumps are made from the bridge span, which has a clearance of 220 feet.

- Anyway, regarding terminal velocity: I think it's more accurate to go with what the slowest TV for a human is, as one could fall in that position and then shift to preferred landing position late enough that you don't then fully accelerate to the higher TV before impact. Some handwaving suggests that 175-200 meters is sufficient fall distance to reach 210 km/h (the TV article suggests that ~195 km/h is the slowest somebody could fall). — Lomn 22:03, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Oh, and as for the last part (getting a parachute mid-air): I have no idea if it's been documented, but it's certainly achievable. Skydiver teams do mid-air rendezvous as a matter of course; handing off a parachute (sans most of the safety straps) or buckling onto someone with one isn't much more difficult. While I might characterize it as "crazy", I wouldn't call it "suicidal". — Lomn 22:08, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Note that those operations are very dangerous, as skydivers can reach extremely high horizontal speeds. I read one account where two divers whacked into each other so hard, one guy's leg was torn off! --Sean 00:04, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- Oh, and as for the last part (getting a parachute mid-air): I have no idea if it's been documented, but it's certainly achievable. Skydiver teams do mid-air rendezvous as a matter of course; handing off a parachute (sans most of the safety straps) or buckling onto someone with one isn't much more difficult. While I might characterize it as "crazy", I wouldn't call it "suicidal". — Lomn 22:08, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Vesna Vulovic managed 33,000 feet without a chute! Also, read this *hilarious* essay; it's awesome. --Sean 00:04, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- Vesna may not have had a parachute, but she was strapped in a section of the fuselage, which limited the velocity she reached before striking the ground. I have descended safely from such a height myself, in an airplane fuselage (but an intact one). Not comparable to a human without chute or plane. Edison (talk) 01:47, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- Robert Langdon in Angels and Demons fell from a pretty good height if i remember correctly. Though he did have a tarp. --Omnipotence407 (talk) 03:37, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- Vesna may not have had a parachute, but she was strapped in a section of the fuselage, which limited the velocity she reached before striking the ground. I have descended safely from such a height myself, in an airplane fuselage (but an intact one). Not comparable to a human without chute or plane. Edison (talk) 01:47, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

Going without orgasm for a long time

If I do not ejaculate for several days, my testicles become painful. I wonder how men in environments where ejaculation is not possible, such as in the Apollo spaceship or in a submarine, cope? Don't they have sex on the mind all the time to the exclusion of everything else, and pernament erections? 80.0.105.180 (talk) 20:09, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- As strange as it may seem, persons aboard spacecraft and in submarines don't -always- have sex on the mind. They are trying to run some of the most technologically advanced machines in existance, of course. Erections only come from arousing thoughts, etc. (excluding "morning-woods" and the likes). If their minds are wholly focused on something else, such as piloting the Apollo spaceshuttle, then it is unlikely they will have "perpetual erections" and therefor will feel no need to ejaculate. —Preceding unsigned comment added by EWHS (talk • contribs) 20:16, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- If your testicles become painful, you should see your doctor about it. Masturbation isn't necessary and going without it should have no harmful consequences (other than perhaps boredom, I guess). Think of monks. —Keenan Pepper 22:09, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Sounds like its possible the OP could be suffering from a case of blue balls. Constant erections and no climax may result in that particularly painful situation. An ejaculation or a cold shower would probably make it stop hurting. [THAT WAS IN NO WAY MEDICAL ADVICE; GO SEE YOUR DOCTOR FOR A PROPER DIAGNOSIS] Also, accomplished astronauts and scientists have already gone through their hormonal teenage years (not to say that they are never horny anymore), and probably have more important things on their mind than constantly thinking of sex. --71.98.28.243 (talk) 22:16, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Huh? At what age are you supposed to stop thinking about sex constantly? I'm well beyond my hormonal teenage years and I guess that I still think about sex approximately every couple of minutes... ;) --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 22:34, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- I'm pretty sure that if they're *really* desperate, then there's one of those 'it's not gay if...' 'loopholes' that covers submariners and astronauts. EDIT: Anyhow, they have women under the sea and in space now, don't they? ;) --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 22:37, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Not in the US Navy: [1]. They're sticking to rum, sodomy, and the lash, I guess. --Sean 00:10, 9 January 2008 (UTC)

- Indeed, for pain in your testicles, see a G-D doctor right fast. Beyond that, bear in mind that the plural of anecdote is not data (and the singular of anecdote is definitely not data) but it's rather hard to go more than about three months without an orgasm (at least for postpubscent males) - your body has a tendancy to just go ahead and do it without your permission anyways. Cheers, WilyD 22:55, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Sorry to say that painful testicles is a medical condition and you should see your doctor. We cannot answer medical questions here.--TreeSmiler (talk) 23:45, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- The body's normal response to not having orgasms is an involuntary orgasm knowns as a wet dream. If your body isn't taking care of things properly by itself, you should probably see a doctor. --67.185.172.158 (talk) 10:12, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

Hydrogen peroxide solution still good?

I know that H202 breaks down somewhat over time, but I don't have a sense for how rapidly this happens. I have a two year old bottle of 30% H2O2 that has been refrigered since receipt. I intend to use in converting formic acid to performic acid. From a practical point of view, do you think this bottle of H2O2 is still good, or should be replaced? It is cheap, but there are shipping charges and of course I'd have to wait for it. ike9898 (talk) 20:36, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- If you're in a chem lab, there's an easy way to tell. Just add a little manganese dioxide to a sample of the H2O2 and measure the volume of oxygen gas evolved. You can determine the concentration of peroxide from that. —Keenan Pepper 22:04, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- H2O2 decomposes spontaneously as it says here Hydrogen_peroxide#Decomposition--TreeSmiler (talk) 23:54, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- But unfortunately the article doesn't say how fast. Another issue: It confuses me that the article says that lower concentrations decompose faster - shouldn't the decomposition rate be proportional to the square of the concentration since the reaction requires 2 molecules of H2O2 to collide? Icek (talk) 00:42, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- Its variable:

- The rate of decomposition is dependent on the temperature and concentration of the peroxide, as well as the pH and the presence of impurities and stabilizers. Hydrogen peroxide is incompatible with many substances that catalyse its decomposition, including most of the transition metals and their compounds. Common catalysts include manganese dioxide, and silver. The same reaction is catalysed by the enzyme catalase, found in the liver, whose main function in the body is the removal of toxic byproducts of metabolism and the reduction of oxidative stress. The decomposition occurs more rapidly in alkali, so acid is often added as a stabilizer.

- But unfortunately the article doesn't say how fast. Another issue: It confuses me that the article says that lower concentrations decompose faster - shouldn't the decomposition rate be proportional to the square of the concentration since the reaction requires 2 molecules of H2O2 to collide? Icek (talk) 00:42, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

--TreeSmiler (talk) 00:53, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- Nonetheless it would be nice if we had some data for a nearly pure H2O2 and water mixture, at a common temperature, in a common inert container. Icek (talk) 04:32, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

I am more interested in practical guidelines used in laboratories that use this substance. In my situation (described in the original question) would it be discarded and replaced? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Ike9898 (talk • contribs) 14:22, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- Sorry, the decomposition rate also depends on dissolved oxygen, which in turn depends on things like the area of the liquid-air interface and the volume of the airspace in the remainder of the bottle. Call the manufacturer and ask. MilesAgain (talk) 14:57, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

energy efficient houses

How does a energy efficient house (E.E.H) helpp stop air polution? What bad and good things does a normal US house do to the enviornment such as light polution? What bad and good things does a normal US E.E.H do to the enviornment? What types of things give off VOC's that are used in houses and what things give off the most VOC's? How much VOC's does the average US house give off and how VOC's does the average US E.E.H give off?

thanks —Preceding unsigned comment added by 76.235.160.188 (talk) 21:25, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

molds and organisms

how do the structures of the slime molds differ from those of cellular organisms —Preceding unsigned comment added by 72.147.252.127 (talk) 21:57, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- If you haven't checked it out already, slime mold has relevant information. — Scientizzle 22:02, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

Whiskers

I've been told that the whiskers on cats are approximately as long as the cat is wide. This makes sense, seeing as they like to go in narrow, tight places and would need to judge as to whether they could fit or not. So my question is HOW the heck to the whiskers grow to that specific length? How do they "know" when to stop growing? Thanks. --71.98.28.243 (talk) 22:10, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- I don't think it's true. My cat's whiskers are quite a bit longer than she is wide. Deli nk (talk) 22:16, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Actually, according to this site, "The whiskers are roughly the same width of the cat, so he can put his head in a small area and determine if the rest will follow. Interestingly, if you cat gets overly chubby, he loses this ability, since the whisker length is determined by genetics, not by how fat the cat is."

- Conversely, this site claims that "If a cat gets quite fat and resembles a barrel, at least some of those whiskers will grow longer in response to the added girth."

- What I don't understand is how do the whiskers (or genes or whatever dictates length) "know" when to stop growing? What allows them to "know" the girth of the cat, therefor dictating the length of the whiskers? --71.98.28.243 (talk) 22:33, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Whiskers grow from modified hair follicles, which have a life cycle of three hair growth phases. A number of different genes are known to be involved in regulating growth, these include Insulin-like growth factors and fibroblast growth factors and Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β). The exact interaction of genes that tells the hair to stop growing is not yet known, to quote a review on the subject: [2]

- Why does the [growth] cycle end when it does? Is this due to the fact that a limited number of mitoses of the transit amplifying cell population becomes exhausted? Or, is it due to a change in the paracrine factor milieu, such as to the accumulation of growth inhibition and proapoptotic agents, or to changes in activities of perifollicular mast cells and macrophages, or to a combination of all of the above? The unknown signal, either inherent in or delivered to the follicle, causes the cycling, deep, portion of the follicle to involute at a surprisingly rapid rate. This phase, catagen, is a highly controlled process of coordinated cell differentiation and apoptosis, involving the cessation of cell growth and pigmentation, release of the papilla from the bulb, loss of the layered differentiation of the lower follicle, substantial extracellular matrix remodeling, and vectorial shrinkage (distally) of the inferior follicle by the process of apoptosis.

- Rockpocket 23:19, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Thanks Rockpocket, I'll try to mull this one over and figure it out. This is a bit more advanced than my normal biology homework ;) --71.98.28.243 (talk) 00:04, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- It is quite wordy. Let me try and translate. The authors speculate about a few explanations for how the hair knows how to stop. They suggest it could be because:

- Some of the cells that are involved in producing the whiskers - the so called transit amplifying cells - can only divide a certain amount of times before they stop. When they stop dividing, they can no longer produce enough material to drive whisker production and so the whisker stops growing.

- There is a steady accumulation of signaling proteins being produced by surrounding cells to tell the whisker cells what do to, signals that tell the whisker growing cells to stop growing and begin to die could be released slowly, however eventually enough of them will accumulate so to over-ride the "grow" signals and the hair stops growing.

- Certain types of cells around the follicle get more active and basically start killing the whiker growing cells.

- These are all good hypotheses about how the whisker stops growing, but the question then because what genetic factors regulate these processes to co-ordinate the whiskers to be the correct length. That is yet to be worked out. Rockpocket 03:03, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- It is quite wordy. Let me try and translate. The authors speculate about a few explanations for how the hair knows how to stop. They suggest it could be because:

- Thanks Rockpocket, I'll try to mull this one over and figure it out. This is a bit more advanced than my normal biology homework ;) --71.98.28.243 (talk) 00:04, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

Three big cocks!

Okay, now that I've got your attention...

I happened to be observing a flock of chickens today (my grandma's window in the old folks' home looks out onto someone's garden) when I noticed that amongst the 20 or so hens, there were three (very large) fully-grown cockerels happily coexisting amongst them. Okay, so if one got a little too close to another, there'd be a little bit of beak lunging and bickering (as happens constantly with my beloved gulls) - but on the whole, they seemed to be getting along rather well.

Now, I remember someone stating here on this desk that it is impossible to keep more than one cockerel per flock, as they would undoubtedly fight one another to the death at the first opportunity. The garden was in no way large enough for each cock to have his own territory either - all the birds were intermingling.

Question - how do you think that the owner managed to stop the violence? Would it make any difference if the birds were siblings? --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 22:57, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- It's common to keep one rooster intact to lord over the flock, while any others who hatch are caponized, which makes them less pugnacious, not to mention fatter and tastier. --Sean 23:53, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- Not in the UK (where I am), according to that article... --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 23:57, 7 January 2008 (UTC)

- If the roosters are raised together in the natural "family situation" with a mother hen etc. then they live fairly peacefully. Roosters raised this way also show all the positive traits such as defending the flock against predators and finding food for the flock. Roosters raised only with other chicks invariably end up as horrible delinquents.Polypipe Wrangler (talk) 11:12, 8 January 2008 (UTC)

- Yes, it appeared to me as though the chickens were being left to their own devices most of the time. Just someone keeping them for the eggs and the odd bit of meat, by the looks of things. Your comment reminds me of the behaviour problems that budgerigars exhibit after being kept as lone pets for a long time before being reintroduced to others of their kind. They don't like it at all and can become very aggressive, especially when it comes to food and favoured objects. I suppose it's just because they've never had the opportunity to learn at first hand how their own species is supposed to behave in a group situation. --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 20:32, 8 January 2008 (UTC)