Moore's law

Moore's Law describes an important trend in the history of computer hardware: that the number of transistors that can be inexpensively placed on an integrated circuit is increasing exponentially, doubling approximately every two years.[1] The observation was first made by Intel co-founder Gordon E. Moore in a 1965 paper.[2][3][4] The trend has continued for more than half a century and is not expected to stop for a decade at least and perhaps much longer.[5]

Almost every measure of the capabilities of digital electronic devices is linked to Moore's Law: processing speed, memory capacity, even the resolution of digital cameras. All of these are improving at (roughly) exponential rates as well. This has dramatically changed the usefulness of digital electronics in nearly every segment of the world economy.[6] Moore's Law describes this driving force of technological and social change in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

History

Moore's original statement that transistor counts had doubled every year can be found in his publication "Cramming more components onto integrated circuits", Electronics Magazine 19 April, 1965:

The complexity for minimum component costs has increased at a rate of roughly a factor of two per year ... Certainly over the short term this rate can be expected to continue, if not to increase. Over the longer term, the rate of increase is a bit more uncertain, although there is no reason to believe it will not remain nearly constant for at least 10 years. That means by 1975, the number of components per integrated circuit for minimum cost will be 65,000. I believe that such a large circuit can be built on a single wafer.[2]

The term Moore's Law was coined around 1970 by the Caltech professor, VLSI pioneer, and entrepreneur Carver Mead.[7][3] Moore may have heard Douglas Engelbart, a co-inventor of today's mechanical computer mouse, discuss the projected downscaling of integrated circuit size in a 1960 lecture.[8]

In 1975, Moore altered his projection to a doubling every two years. Despite popular misconception, he is adamant that he did not predict a doubling "every 18 months." However, an Intel colleague had factored in the increasing performance of transistors to conclude that integrated circuits would double in performance every 18 months.[9]

In April 2005, Intel offered $10,000 to purchase a copy of the original Electronics Magazine.[10] David Clark, an engineer living in the UK, was the first to find a copy and offer it to Intel.[11]

Other formulations and similar laws

Several measures of digital technology are improving at exponential rates related to Moore's Law, including the size, cost, density and speed of components. Note that Moore himself wrote only about the density of components (or transistors) at minimum cost. He noted [12]:

Moore's Law has been the name given to everything that changes exponentially. I say, if Gore invented the Internet, I invented the exponential.

Transistors per integrated circuit. The most popular formulation is of the doubling of the number of transistors on integrated circuits every two years. At the end of the 1970s, Moore's Law became known as the limit for the number of transistors on the most complex chips. Recent trends show that this rate has been maintained into 2007.

Density at minimum cost per transistor. This is the formulation given in Moore's 1965 paper.[2] It is not about just the density of transistors that can be achieved, but about the density of transistors at which the cost per transistor is the lowest.[13] As more transistors are put on a chip, the cost to make each transistor decreases, but the chance that the chip will not work due to a defect increases. In 1965, Moore examined the density of transistors at which cost is minimized, and observed that, as transistors were made smaller through advances in photolithography, this number would increase at "a rate of roughly a factor of two per year".[2]

Cost per transistor. As the size of transistors has decreased, the cost per transistor has decreased as well.[citation needed]

Computing performance per unit cost. Also, as the size of transistors shrinks, the speed at which they operate increases. It is also common to cite Moore's Law to refer to the rapidly continuing advance in computing performance per unit cost, because increase in transistor count is also a rough measure of computer processing performance. On this basis, the performance of computers per unit cost - or more colloquially, "bang per buck" - doubles every 24 months (or, equivalently, increases 32-fold every 10 years).[citation needed]

Hard disk storage cost per unit of information. A similar law (sometimes called Kryder's Law) has held for hard disk storage cost per unit of information.[14] The rate of progression in disk storage over the past decades has actually sped up more than once, corresponding to the utilization of error correcting codes, the magnetoresistive effect and the giant magnetoresistive effect. The current rate of increase in hard drive capacity is roughly similar to the rate of increase in transistor count. Recent trends show that this rate has been maintained into 2007.

RAM storage capacity. Another version states that RAM storage capacity increases at the same rate as processing power.

Data per optical fiber. According to Gerry/Gerald Butters,[15][16] the former head of Lucent's Optical Networking Group at Bell Labs, there is another version, called Butter's Law of Photonics,[17] a formulation which deliberately parallels Moore's law. Butter's Law [18] says that the amount of data coming out of an optical fiber is doubling every nine months. Thus, the cost of transmitting a bit over an optical network decreases by half every nine months. The availability of wavelength-division multiplexing (sometimes called "WDM") increased the capacity that could be placed on a single fiber by as much as a factor of 100. Optical networking and DWDM is rapidly bringing down the cost of networking, and further progress seems assured. As a result, the wholesale price of data traffic collapsed in the dot-com bubble.

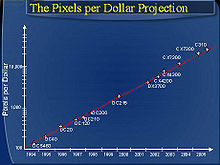

Pixels per dollar. Similarly, Barry Hendy of Kodak Australia has plotted the "pixels per dollar" as a basic measure of value for a digital camera, demonstrating the historical linearity (on a log scale) of this market and the opportunity to predict the future trend of digital camera price and resolution.

A self-fulfilling prophecy: industry struggles to keep up with Moore's Law

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2008) |

Although Moore's Law was initially made in the form of an observation and forecast, the more widely it became accepted, the more it served as a goal for an entire industry. This drove both marketing and engineering departments of semiconductor manufacturers to focus enormous energy aiming for the specified increase in processing power that it was presumed one or more of their competitors would soon actually attain. In this regard, it can be viewed as a self-fulfilling prophecy. For example, the SEMATECH roadmap follows a 24 month cycle.

The implications of Moore's Law for computer component suppliers are very significant. A typical major design project (such as an all-new CPU or hard drive) takes between two and five years to reach production-ready status. In consequence, component manufacturers face enormous timescale pressures—just a few weeks of delay in a major project can spell the difference between great success and massive losses, even bankruptcy. Expressed (incorrectly) as "a doubling every 18 months", Moore's Law suggests phenomenal progress for technology over the span of a few years. Expressed on a shorter timescale, however, this equates to an average performance improvement in the industry as a whole of close to 1% per week. Thus, for a manufacturer in the competitive CPU market, a new product that is expected to take three years to develop and turns out just three or four months late is 10 to 15% slower, bulkier, or lower in capacity than the directly competing products, and is close to unsellable. If instead we accept that performance will double every 24 months, rather than every 18, a three– to four–month delay would translate to 8–11% lower performance.

As the cost of computer power to the consumer falls, the cost for producers to fulfill Moore's Law follows an opposite trend: R&D, manufacturing, and test costs have increased steadily with each new generation of chips. As the cost of semiconductor equipment is expected to continue increasing, manufacturers must sell larger and larger quantities of chips to remain profitable. (The cost to tape-out a chip at 180 nm was roughly US$300,000. The cost to tape-out a chip at 90 nm exceeds US$750,000, and is expected to exceed US$1,000,000 for 65 nm. [citation needed]) In recent years, analysts have observed a decline in the number of "design starts" at advanced process nodes (130 nm and below for 2007). While these observations were made in the period after the 2000 economic downturn, the decline may be evidence that traditional manufacturers in the long-term global market cannot economically sustain Moore's Law.

Future trends

Computer industry technology "road maps' predict (as of 2001) that Moore's Law will continue for several chip generations. Depending on the doubling time used in the calculations, this could mean up to a hundredfold increase in transistor count per chip within a decade. The semiconductor industry technology roadmap uses a three-year doubling time for microprocessors, leading to a tenfold increase in the next decade.[19] Intel was reported in 2005 as stating that the downsizing of silicon chips with good economics can continue during the next decade.[20]

Some of the new directions in research that may allow Moore's law to continue are:

- Intel's prediction of increasing use of materials other than silicon was verified in mid-2006, as was its intent of using trigate transistors from around 2009 [citation needed].

- Researchers from IBM and Georgia Tech created a new speed record when they ran a silicon/germanium helium supercooled transistor at 500 gigahertz (GHz).[21] The transistor operated above 500 GHz at 4.5 K (−451°F/−268.65°C)[22] and simulations showed that it could likely run at 1 THz (1,000 GHz), although this was only a single transistor, and practical desktop CPUs running at this speed are extremely unlikely using contemporary silicon chip techniques [citation needed].

- In early 2006, IBM researchers announced that they had developed a technique to print circuitry only 29.9 nm wide using deep-ultraviolet (DUV, 193-nanometer) optical lithography. IBM claims that this technique may allow chipmakers to use current methods for seven years while continuing to achieve results forecast by Moore's Law. New methods that can achieve smaller circuits are expected to be substantially more expensive.

- On January 27, 2007, Intel demonstrated a working 45nm chip codenamed "Penryn", intending mass production to begin in late 2007.[23] A decade ago, chips were built using a 500 nm process.

- Companies are working on using nanotechnology to solve the complex engineering problems involved in producing chips at the 32 nm and smaller levels. (The diameter of an atom is on the order of 0.1 nm.)

While this time horizon for Moore's Law scaling is possible, it does not come without underlying engineering challenges. One of the major challenges in integrated circuits that use nanoscale transistors is increase in parameter variation and leakage currents. As a result of variation and leakage, the design margins available to do predictive design are becoming harder. Such systems also dissipate considerable power even when not switching. Adaptive and statistical design along with leakage power reduction is critical to sustain scaling of CMOS. A good treatment of these topics is covered in Leakage in Nanometer CMOS Technologies. Other scaling challenges include:

- The ability to control parasitic resistance and capacitance in transistors,

- The ability to reduce resistance and capacitance in electrical interconnects,

- The ability to maintain proper transistor electrostatics to allow the gate terminal to control the ON/OFF behavior,

- Increasing effect of line edge roughness,

- Dopant fluctuations,

- System level power delivery,

- Thermal design to effectively handle the dissipation of delivered power, and

- Solving all these challenges at an ever-reducing manufacturing cost of the overall system.

Ultimate limits of the law

In 1995, the "powerful" DEC Alpha chip (acquired by Compaq, now part of Hewlett-Packard) was made up of approximately nine million transistors. This 64-bit processor was a technological spearhead at the time, even if the circuit’s market share remained average. Six years later, a state of the art microprocessor would have more than 40 million transistors. In 2015, it is believed that these processors should contain more than 15 billion transistors. Things are becoming smaller each year. If this continues, in theory, in less than 10 years computers will be created where each molecule will have its own place, i.e. we will have completely entered the era of molecular scale production. [24].

Seth Lloyd states[25] that we could have the whole universe simulated in a computer in 600 years provided that computational power increases according to Moore's Law. However, Lloyd shows that there are limits to rapid exponential growth in a finite universe, and that it is very unlikely that Moore's Law will be maintained indefinitely.

On April 13, 2005, Gordon Moore himself stated in an interview that the law cannot be sustained indefinitely: "It can't continue forever. The nature of exponentials is that you push them out and eventually disaster happens." and noted that transistors would eventually reach the limits of miniaturization at atomic levels:

In terms of size [of transistor] you can see that we're approaching the size of atoms which is a fundamental barrier, but it'll be two or three generations before we get that far—but that's as far out as we've ever been able to see. We have another 10 to 20 years before we reach a fundamental limit. By then they'll be able to make bigger chips and have transistor budgets in the billions.[26]

Lawrence Krauss and Glenn D. Starkman announced an ultimate limit of around 600 years in their paper "Universal Limits of Computation", based on rigorous estimation of total information-processing capacity of any system in the Universe.

Then again, the law has often met obstacles that appeared insurmountable, before soon surmounting them. In that sense, Moore says he now sees his law as more beautiful than he had realized: "Moore's Law is a violation of Murphy's Law. Everything gets better and better."[27]

Futurists and Moore's Law

Extrapolation partly based on Moore's Law has led futurists such as Vernor Vinge, Bruce Sterling, and Ray Kurzweil to speculate about a technological singularity. Kurzweil projects that a continuation of Moore's Law until 2019 will result in transistor features just a few atoms in width. Although this means that the strategy of ever finer photolithography will have run its course, he speculates that this does not mean the end of Moore's Law:

Moore's Law of Integrated Circuits was not the first, but the fifth paradigm to forecast accelerating price-performance ratios. Computing devices have been consistently multiplying in power (per unit of time) from the mechanical calculating devices used in the 1890 U.S. Census, to [Newman's] relay-based "[Heath] Robinson" machine that cracked the [Nazi Lorenz cipher], to the CBS vacuum tube computer that predicted the election of Eisenhower, to the transistor-based machines used in the first space launches, to the integrated-circuit-based personal computer.[28]

Thus, Kurzweil conjectures that it is likely that some new type of technology will replace current integrated-circuit technology, and that Moore's Law will hold true long after 2020. He believes that the exponential growth of Moore's Law will continue beyond the use of integrated circuits into technologies that will lead to the technological singularity. The Law of Accelerating Returns described by Ray Kurzweil has in many ways altered the public's perception of Moore's Law. It is a common (but mistaken) belief that Moore's Law makes predictions regarding all forms of technology, when it actually only concerns semiconductor circuits. Many futurists still use the term "Moore's Law" in this broader sense to describe ideas like those put forth by Kurzweil.

Software: breaking the law

A sometimes misunderstood point is that exponentially improved hardware does not necessarily imply exponentially improved software performance to go with it. The productivity of software developers most assuredly does not increase exponentially with the improvement in hardware, but by most measures has increased only slowly and fitfully over the decades. Software tends to get larger and more complicated over time, and Wirth's law even states humorously that "Software gets slower faster than hardware gets faster".

There are problems where exponential increases in processing power are matched or exceeded by exponential increases in complexity as the problem size increases. (See computational complexity theory and complexity classes P and NP for a (somewhat theoretical) discussion of such problems, which occur very commonly in applications such as scheduling.)

Due to the mathematical power of exponential growth (similar to the financial power of compound interest), seemingly minor fluctuations in the relative growth rates of CPU performance, RAM capacity, and disk space per dollar have caused the relative costs of these three fundamental computing resources to shift markedly over the years, which in turn has caused significant changes in programming styles. For many programming problems, the developer has to decide on numerous time-space tradeoffs, and throughout the history of computing these choices have been strongly influenced by the shifting relative costs of CPU cycles versus storage space.

Other considerations

Not all aspects of computing technology develop in capacities and speed according to Moore's Law. Random Access Memory (RAM) speeds and hard drive seek times improve at best a few percentage points each year. Since the capacity of RAM and hard drives is increasing much faster than is their access speed, intelligent use of their capacity becomes more and more important. It now makes sense in many cases to trade space for time, such as by precomputing indexes and storing them in ways that facilitate rapid access, at the cost of using more disk and memory space: space is getting cheaper relative to time.

Moreover, there is a popular misconception that the clock speed of a processor determines its speed, also known as the Megahertz Myth. This actually also depends on the number of instructions per tick which can be executed (as well as the complexity of each instruction, see MIPS, RISC and CISC), and so the clock speed can only be used for comparison between two identical circuits. Of course, other factors must be taken into consideration such as the bus width and speed of the peripherals. Therefore, most popular evaluations of "computer speed" are inherently biased, without an understanding of the underlying technology. This was especially true during the Pentium era when popular manufacturers played with public perceptions of speed, focusing on advertising the clock rate of new products.[29]

Another popular misconception circulating Moore's Law is the incorrect assumption that exponential processor transistor growth, as predicted by Moore, translates directly into proportional exponential increase processing power or processing speed. While the increase of transistors in processors usually have an increased effect on processing power or speed, the relationship between the two factors in not proportional. There are cases where a ~45% increase in processor transistors[30] have translated to roughly 10-20% increase in processing power or speed. Different processor families have different performance increases when transistor count is increased. More precisely, processor performance or power is more related to other factors such as microarchitecture, and clock speed within the same processor family. That is to say, processor performance can increase without increasing the number of transistors in a processor. (AMD64 processors had better overall performance[31] compared to the late Pentium 4 series, which had more transistors)

It is also important to note that transistor density in multi-core CPUs does not necessarily reflect a similar increase in practical computing power, due to the unparallelised nature of most applications.

See also

- Accelerating change

- Amdahl's law

- Bell's Law

- Experience curve effects

- Exponential growth

- Gates' Law

- History of computing hardware (1960s-present)

- Hofstadter's Law

- Kryder's Law

- Logistic growth

- Observations named after people

- Quantum Computing

- Rock's Law

- Second Half of the Chessboard

- Semiconductor

- Wirth's Law "Software gets slower faster than hardware gets faster."

References and notes

- ^ Although originally calculated as a doubling every year,[1] Moore later refined the period to two years.[2] It is often incorrectly quoted as a doubling of transistors every 18 months.

- ^ a b c d Moore, Gordon E. (1965). "Cramming more components onto integrated circuits" (PDF). Electronics Magazine. p. 4. Retrieved November 11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Moore1965paper" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b "Excerpts from A Conversation with Gordon Moore: Moore's Law" (PDF). Intel Corporation. 2005. p. 1. Retrieved May 2.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^

"1965 - "Moore's Law" Predicts the Future of Integrated Circuits" (html). Computer History Museum. ??. Retrieved November.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|year=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Kanellos, Michael (10 February 2003). "Moore's law to roll on for another decade". cnet.

- ^

Rauch, Jonathan (01 January 2001), "The New Old Economy: Oil, Computers, and the Reinvention of the Earth", The Atlantic Monthly

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ NY Times article April 17, 2005

- ^ Although it is often misquoted as a doubling every 18 months, Intel's official Moore's Law page, as well as an interview with Gordon Moore himself, states that it is every two years.

- ^ Michael Kanellos (2005-04-12). "$10,000 reward for Moore's Law original". CNET News.com.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Moore's Law original issue found". BBC News Online. 2005-4-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue7_11/tuomi/index.html

- ^ Understanding Moore's Law

- ^ Walter, Chip (2005-07-25). "Kryder's Law". Scientific American. (Verlagsgruppe Georg von Holtzbrinck GmbH). Retrieved 2006-10-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Forbes.com - Profile - Gerald Butters is a communications industry veteran

- ^ LAMBDA OpticalSystems - Board of Directors - Gerry Butters

- ^ As We May Communicate

- ^ Speeding net traffic with tiny mirrors

- ^ International Technology Roadmap

- ^ "New life for Moores Law". CNET News.com. 2006-04-19.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Chilly chip shatters speed record". BBC Online. 2006-06-20.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Georgia Tech/IBM Announce New Chip Speed Record". Georgia Institute of Technology. 2006-06-20.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^

"Meet the world's first 45 nm transistors". Intel. 2007-01-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Waldner, Jean-Baptiste (2008). Nanocomputers and Swarm Intelligence. London: ISTE John Wiley & Sons. pp. p44-45. ISBN 1847040020.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Lloyd, S. (2000-08-31). "Ultimate physical limits to computation" (PDF). Nature. 406: 1047–1054.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Manek Dubash (2005-04-13). "Moore's Law is dead, says Gordon Moore". Techworld.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^

"Moore's Law at 40 - Happy birthday". The Economist. 2005-03-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Ray Kurzweil (2001-03-07). "The Law of Accelerating Returns". KurzweilAI.net.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Matthew Broersma (2006-06-24). "Intel, Aberdeen attack AMD speed ratings". ZDNet UK.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Anand Lal Shimpi (2004-07-21). "AnandTech: Intel's 90nm Pentium M 755: Dothan Investigated". Anadtech.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Ilya Gavrichenkov (2005-02-20). "X-bit labs - Intel Pentium 4 6XX and Intel Pentium 4 Extreme Edition 3.73GHz CPU Review (page 21)". X-bit labs.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

External links

Articles

- Intel's information page on Moore's Law – With link to Moore's original 1965 paper

- Intel press kit released for Moore's Law's 40th anniversary, with a 1965 sketch by Moore

- The Lives and Death of Moore's Law – By Ilkka Tuomi; a detailed study on Moore's Law and its historical evolution and its criticism by Kurzweil.

- Moore says nanoelectronics face tough challenges – By Michael Kanellos, CNET News.com, 9 March, 2005

- Moore's Law – Blog and news; Moore's Law graph showing estimated end time, other related graphics

- It's Moore's Law, But Another Had The Idea First by John Markoff

- Law that has driven digital life: The Impact of Moore's Law – A comprehensive BBC News article, 18 April, 2005

- No More Moore's Law? - BBC News article, 22 July 2004

- IBM Research Demonstrates Path for Extending Current Chip-Making Technique – Press release from IBM on new technique for creating line patterns, 20 February, 2006

- Understanding Moore's Law By Jon Hannibal Stokes 20 February 2003

- The Technical Impact of Moore's Law IEEE solid-state circuits society newsletter; September 2006

- MIT Technology Review article: Novel Chip Architecture Could Extend Moore's Law

- Moore's Law seen extended in chip breakthrough

- Intel Says Chips Will Run Faster, Using Less Power

- A ZDNet article detailing the limits

Data

- Intel (IA-32) CPU Speeds since 1994. Speed increases in recent years have seemed to slow down with regard to percentage increase per year (available in PDF or PNG format).

- A case for PC upgrade, 2002-2007.