Czesław Miłosz

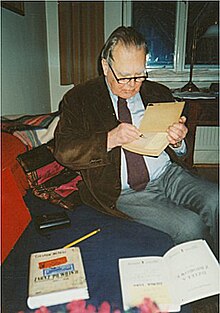

Czesław Miłosz, Kraków, December 1998. | |

| Born | June 30, 1911, Šeteniai, near Kėdainiai. |

| Died | August 14, 2004 (aged 93), Kraków. |

| Occupation | Poet, essayist. |

Czesław Miłosz ; (June 30, 1911 – August 14, 2004) was a Polish poet, writer, academic, and translator. In 1961 he became a professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1980 he won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Life

Czesław Miłosz was born on June 30, 1911, at Šeteniai (Polish: Szetejnie), in what was then part of the Russian Empire (and is now in Lithuania), into a szlachta family of the Lubicz coat of arms[citation needed]. He emphasized his family connections with the ancient Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which had been part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. While Miłosz was a Pole, he once said of himself: "I am a Lithuanian to whom it was not given to be a Lithuanian."[1]

He had a brother, Andrzej Miłosz (1917 – 2002), a Polish journalist, translator of literature and film subtitles, and documentary-film producer (who created some documentaries about his famous brother).

Czesław Miłosz passed some of his childhood in the Russian Empire around the time of the 1917 Russian Revolution. He graduated from Sigismund Augustus Gymnasium in Vilnius, and studied law at Stefan Batory University (now Vilnius University), then a Polish-language institution of higher learning in what was part of Poland. He wrote all his poetry and fiction in Polish and translated the Old Testament Psalms into Polish.

He spent World War II in Warsaw, Poland, where, among other things, he attended underground lectures by Polish philosopher and historian of philosophy and aesthetics, Władysław Tatarkiewicz.

After World War II he served as cultural attaché of the communist People's Republic of Poland in Paris. In 1951 Miłosz broke with his government and obtained political asylum in France. In 1953 he received the Prix Littéraire Européen (European Literary Prize).

In 1960 Miłosz moved to the United States, and in 1970 he became a U.S. citizen. In 1961 he began a professorship in Polish literature in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1978 Miłosz received the Neustadt International Prize for Literature. He retired that same year, but continued teaching at Berkeley.

In 1980 he received the Nobel Prize for Literature. Since his works had been banned in Poland by the communist government, this was the first time that many Poles became aware of him.

When the Iron Curtain fell, Miłosz was able to return to Poland, at first to visit and later to live there part-time.

In 1989 Miłosz received the National Medal of Arts and an honorary doctorate from Harvard University.

Through the Cold War, Miłosz's name was often invoked in the United States, particularly by conservative commentators such as William F. Buckley, Jr., usually in the context of Miłosz's 1953 book The Captive Mind. During this period, his name was largely passed over in silence in government-censored media and publications in Poland.

The Captive Mind has been described as one of the finest studies of the behavior of intellectuals under a repressive regime. Miłosz observed that those who became dissidents were not necessarily those with the strongest minds, but rather those with the weakest stomachs. The mind can rationalize anything, he said, but the stomach can take only so much. Miłosz also claimed that, as a poet, he avoided touching his nation's wounds for fear of making them holy.

Miłosz is honored at Israel's Yad Vashem memorial to the Holocaust, as one of the "Righteous among the Nations." A poem by him appears on a memorial to shipyard workers who were killed at Gdańsk in 1970.

His books and poems have been translated into English by many hands, including Jane Zielonko (The Captive Mind), Miłosz himself, his Berkeley students (in translation seminars conducted by him), and his friends and Berkeley colleagues, Peter Dale Scott, Robert Pinsky and Robert Hass.

Miłosz spoke English with a Polish accent. Once, during a 1966 lecture at the University of California, Berkeley, he startled students with a reference to "the Juice in Poland" (he had meant "the Jews in Poland").

Miłosz took pleasure in occasionally deflating academic pomposity, as when he recounted the stir he had caused at a literary conference by referring to "turpism" (same root as the English "turpitude"), which some at the conference had taken to be a new literary movement.

Though somewhat reserved in manner, in the 1960s he would playfully greet a coed with "How's your sex life?"

Miłosz died in 2004 at his Kraków home, aged 93. His first wife, Janina, had died in 1986; and his second wife, Carol, a U.S.-born historian, in 2002. Miłosz is entombed at Kraków's historic Skałka Church.

Works

- Kompozycja (1930)

- Podróż (1930)

- Poemat o czasie zastygłym (1933)

- Trzy zimy / Three Winters (1936)

- Obrachunki

- Wiersze / Verses (1940)

- Pieśń niepodległa (1942)

- Ocalenie / Rescue (1945)

- Traktat moralny / A Moral Treatise (1947)

- Zniewolony umysł / The Captive Mind (1953)

- Zdobycie władzy / The Seizure of Power (1953)

- Światło dzienne / The Light of Day (1953)

- Dolina Issy / The Issa Valley (1955)

- Traktat poetycki / A Poetical Treatise (1957)

- Rodzinna Europa / Native Realm (1958)

- Kontynenty (1958)

- Człowiek wśród skorpionów (1961)

- Król Popiel i inne wiersze / King Popiel and Other Poems (1961)

- Gucio zaczarowany / Gucio Enchanted (1965)

- Widzenia nad Zatoką San Francisco / Visions of San Francisco Bay (1969)

- Miasto bez imienia / City Without a Name (1969)

- The History of Polish Literature (1969)

- Prywatne obowiązki / Private Obligations (1972)

- Gdzie słońce wschodzi i kiedy zapada / Where the Sun Rises and Where It Sets (1974)

- Ziemia Ulro / The Land of Ulro (1977)

- Ogród nauk / The Garden of Learning (1979)

- Hymn o perle / The Poem of the Pearl (1982)

- The Witness of Poetry (1983)

- Nieobjęta ziemio / The Unencompassed Earth (1984)

- Kroniki / Chronicles (1987)

- Dalsze okolice / Farther Surroundings (1991)

- Zaczynając od moich ulic / Starting from My Streets (1985)

- Metafizyczna pauza / The Metaphysical Pause (1989)

- Poszukiwanie ojczyzny (1991)

- Rok myśliwego (1991)

- Na brzegu rzeki / Facing the River (1994)

- Szukanie ojczyzny / In Search of a Homeland (1992)

- Legendy nowoczesności / Modern Legends (1996)

- Życie na wyspach / Life on Islands (1997)

- Piesek przydrożny / Roadside Dog (1997)

- Abecadlo Miłosza / Milosz's Alphabet (1997)

- Inne Abecadło / A Further Alphabet (1998)

- Wyprawa w dwudziestolecie / An Excursion through the Twenties and Thirties (1999)

- To / It (2000)

- Orfeusz i Eurydyka (2003)

- O podróżach w czasie / On Time Travel (2004)

- Wiersze ostatnie / The Last Poems (2006)

Notes

- ^ Template:Lt icon "Išėjus Česlovui Milošui, Lietuva neteko dalelės savęs". Mokslo Lietuva (Scientific Lithuania) (in Lithuanian).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

References

- Striving Towards Being: The Letters of Thomas Merton and Czesław Miłosz, edited by Robert Faggen (Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1996)

Obituaries

- IN MEMORIAM Czesław Miłosz (UC Berkeley)

- Nobel poet Czesław Miłosz of Poland and Berkeley, one of the icons of the Solidarity movement, dies (UC Berkeley Press Release)

- Czeslaw Milosz, 1911-2004 (New York Times)

- Czesław Miłosz, Poet and Nobelist Who Wrote of Modern Cruelties, Dies at 93 (New York Times)

- Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz dies (CBC News)

- Nobel laureate poet Miłosz dies (BBC News)

- Czesław Miłosz Obituary (The Economist)

- Czesław Miłosz memorial (San Francisco Chronicle)

- Polish Poet Czeslaw Milosz, 93, Dies (Washington Post)

- The “Memory” of Czeslaw Milosz, 1911 – 2004 (New Criterion)

External links

- Milosz.pl — official website of Czesław Miłosz (Polish)

- Interview with Czesław Miłosz (Georgia Review)

- Open Directory Project: Czesław Miłosz

- Biography of Czesław Miłosz

- Miłosz reading his poems in English and in Polish at the Internet Poetry Archive on ibiblio.org

- Miłosz reading his poems in English at UC Berkeley, February 3, 2000 (online audio file)

- Miłosz reading his poems in English at UC Berkeley, April 4, 1983 (with Robert Hass and Robert Pinksy (online audio file)

- Information relating to Miłosz as the winner of the 1980 Nobel Prize in Literature (official site)

- Nobel Prize acceptance speech [1]

- Encyclopedia Britannica

- American Academy of Poets

- 1911 births

- 2004 deaths

- Polish diplomats

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- Polish nobility

- Righteous Among the Nations

- Polish Nobel laureates

- Polish writers

- Polish political writers

- Polish poets

- Roman Catholic writers

- Polish translators

- Translators from Polish

- Polish-English translators

- Polish Lithuanians