Anarcho-capitalism

This article's lead section may be too long. |

It has been suggested that Free-market anarchism and Talk:Free-market anarchism#Redirect be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since March 2008. |

Anarcho-capitalism or free-market anarchism[1] (a form of individualist anarchism)[2] is an anti-state political philosophy that attempts to reconcile anarchism with capitalism. It advocates the elimination of the state; the provision of law enforcement, courts, national defense, and all other security services by voluntarily-funded competitors in a free market rather than through compulsory taxation; the complete deregulation of nonintrusive personal and economic activities; and a self-regulated market. Anarcho-capitalists argue for a society based in voluntary trade of private property (including money, consumer goods, land, and capital goods) and services in order to maximize individual liberty and prosperity, but also recognize charity and communal arrangements as part of the same voluntary ethic.[3] Though anarcho-capitalists are known for asserting a right to private (individualized/non-public) property, non-state common property can also exist in an anarcho-capitalist society.[4] For them, what is important is that it is acquired and transferred without help or hindrance from the compulsory state. Anarcho-capitalist libertarians believe that the only just way to acquire property is through voluntary trade, gift, or labor-based original appropriation, rather than through aggression or fraud. Murray Rothbard coined the term anarcho-capitalism to distinguish it from anarchism that opposes private property.[5]

Anarcho-capitalists see free-market capitalism as the basis for a free society. Rothbard defined free-market capitalism as "peaceful voluntary exchange", in contrast to "state capitalism" which he defined as a collusive partnership between business and government that uses coercion to subvert the free market.[6] "Capitalism," as anarcho-capitalists employ the term, is not to be confused with state monopoly capitalism, crony capitalism, corporatism, or contemporary mixed economies, wherein natural market incentives and disincentives are skewed by state intervention.[7] So they reject the state, based on the belief that states are aggressive entities which steal property (through taxation and expropriation), initiate aggression, are a compulsory monopoly on the use of defensive and/or punitive force, use their coercive powers to benefit some businesses and individuals at the expense of others, create monopolies, restrict trade, and restrict personal freedoms via drug laws, compulsory education, conscription, laws on food and morality, and the like. The embrace of unfettered capitalism leads to considerable tension between anarcho-capitalists and many social anarchists who tend to distrust the market, and believe that free-market capitalism is inherently authoritarian – hence incompatible with Anarchist ideals.

Various theorists have differing, though similar, philosophies which are considered to fall under "anarcho-capitalism." The first well-known version of anarcho-capitalism was formulated by Austrian School economist and libertarian Murray Rothbard in the mid-twentieth century, synthesizing elements from the Austrian School of economics, classical liberalism, and nineteenth century American individualist anarchists Lysander Spooner and Benjamin Tucker (rejecting their labor theory of value and the normative implications they derived from it).[8] In Rothbardian anarcho-capitalism, there would first be the implementation of a mutually agreed-upon libertarian "legal code which would be generally accepted, and which the courts would pledge themselves to follow."[9] This legal code would recognize sovereignty of the individual and the principle of non-aggression. However, in David D. Friedman's anarcho-capitalism, "the systems of law will be produced for profit on the open market",[10] which he believes would lead to a generally libertarian society if not an absolute one. Rothbard bases his philosophy on absolutist natural law grounds but also gives economic explanations of why he thinks anarcho-capitalism is preferable on pragmatic grounds. Friedman says he is not an absolutist rights theorist but is also "not a utilitarian", but believes that "utilitarian arguments are usually the best way to defend libertarian views".[11] Hans-Hermann Hoppe, meanwhile, uses "argumentation ethics" for his foundation of "private property anarchism",[12] which is closer to Rothbard's natural law approach.

Philosophy

The nonaggression axiom

"I define anarchist society as one where there is no legal possibility for coercive aggression against the person or property of any individual. Anarchists oppose the State because it has its very being in such aggression, namely, the expropriation of private property through taxation, the coercive exclusion of other providers of defense service from its territory, and all of the other depredations and coercions that are built upon these twin foci of invasions of individual rights." -Murray Rothbard in Society and State

|

The term anarcho-capitalism was most likely coined in the mid-1950s by the economist Murray Rothbard.[13] Other terms sometimes used for this philosophy, though not necessarily outside anarcho-capitalist circles, include:

|

Anarcho-capitalism, as formulated by Rothbard and others, holds strongly to the central libertarian nonaggression axiom:

- [...] The basic axiom of libertarian political theory holds that every man is a self owner, having absolute jurisdiction over his own body. In effect, this means that no one else may justly invade, or aggress against, another's person. It follows then that each person justly owns whatever previously unowned resources he appropriates or "mixes his labor with." From these twin axioms — self-ownership and "homesteading" — stem the justification for the entire system of property rights titles in a free-market society. This system establishes the right of every man to his own person, the right of donation, of bequest (and, concomitantly, the right to receive the bequest or inheritance), and the right of contractual exchange of property titles.[17]

Rothbard's defense of the self-ownership principle stems from what he believed to be his falsification of all other alternatives, namely that either a group of people can own another group of people, or the other alternative, that no single person has full ownership over one's self. Rothbard dismisses these two cases on the basis that they cannot result in an universal ethic, i.e., a just natural law that can govern all people, independent of place and time. The only alternative that remains to Rothbard is self-ownership, which he believes is both axiomatic and universal.[18]

In general, the nonaggression axiom can be said to be a prohibition against the initiation of force, or the threat of force, against persons (i.e., direct violence, assault, murder) or property (i.e., fraud, burglary, theft, taxation).[19] The initiation of force is usually referred to as aggression or coercion. The difference between anarcho-capitalists and other libertarians is largely one of the degree to which they take this axiom. Minarchist libertarians, such as most people involved in Libertarian political parties, would retain the state in some smaller and less invasive form, retaining at the very least public police, courts and military; others, however, might give further allowance for other government programs. In contrast, anarcho-capitalists reject any level of state intervention, defining the state as a coercive monopoly and, as the only entity in human society that derives its income from legal aggression, an entity that inherently violates the central axiom of libertarianism.[18]

Some anarcho-capitalists, such as Rothbard, accept the nonaggression axiom on an intrinsic moral or natural law basis. It is in terms of the non-aggression principle that Rothbard defined anarchism; he defined "anarchism as a system which provides no legal sanction for such aggression ['against person and property']" and said that "what anarchism proposes to do, then, is to abolish the State, i.e. to abolish the regularized institution of aggressive coercion."[20] In an interview with New Banner, Rothbard said that "capitalism is the fullest expression of anarchism, and anarchism is the fullest expression of capitalism."[21] Alternatively, others, such as Friedman, take a consequentialist or egoist approach; rather than maintaining that aggression is intrinsically immoral, they maintain that a law against aggression can only come about by contract between self-interested parties who agree to refrain from initiating coercion against each other.

Property

Private property

Central to anarcho-capitalism are the concepts of self-ownership and original appropriation:

Everyone is the proper owner of his own physical body as well as of all places and nature-given goods that he occupies and puts to use by means of his body, provided only that no one else has already occupied or used the same places and goods before him. This ownership of "originally appropriated" places and goods by a person implies his right to use and transform these places and goods in any way he sees fit, provided only that he does not change thereby uninvitedly the physical integrity of places and goods originally appropriated by another person. In particular, once a place or good has been first appropriated by, in John Locke's phrase, 'mixing one's labor' with it, ownership in such places and goods can be acquired only by means of a voluntary — contractual — transfer of its property title from a previous to a later owner.[22]

|

Anarcho-capitalism uses the following terms in ways that may differ from common usage or various anarchist movements.

|

This is the root of anarcho-capitalist property rights, and where they differ from collectivist forms of anarchism such as anarcho-communism where the product of labor is collectivized in a pool of goods and distributed "according to need." Anarcho-capitalists advocate individual ownership of the product of labor regardless of what the individual "needs" or does not need. As Rothbard says, "if every man has the right to own his own body and if he must use and transform material natural objects in order to survive, then he has the right to own the product that he has made." After property is created through labor it may then only exchange hands legitimately by trade or gift; forced transfers are considered illegitimate. Original appropriation allows an individual to claim any "unused" property, including land, and by improving or otherwise using it, own it with the same "absolute right" as his own body. According to Rothbard, property can only come about through labor, therefore original appropriation of land is not legitimate by merely claiming it or building a fence around it; it is only by using land — by mixing one's labor with it — that original appropriation is legitimized: "Any attempt to claim a new resource that someone does not use would have to be considered invasive of the property right of whoever the first user will turn out to be."[23] As a practical matter, in terms of the ownership of land, anarcho-capitalists recognize that there are few (if any) parcels of land left on Earth whose ownership was not at some point in time obtained in violation of the homestead principle, through seizure by the state or put in private hands with the assistance of the state. Rothbard says in "Justice and Property Right" that "any identifiable owner (the original victim of theft or his heir) must be accorded his property." In the case of slavery, Rothbard says that in many cases "the old plantations and the heirs and descendants of the former slaves can be identified, and the reparations can become highly specific indeed." He believes slaves rightfully own any land they were forced to work on under the "homestead principle." If property is held by the state, Rothbard advocates its confiscation and return to the private sector: "any property in the hands of the State is in the hands of thieves, and should be liberated as quickly as possible." For example, he proposes that State universities be seized by the students and faculty under the homestead principle. Rothbard also supports expropriation of nominally "private property" if it is the result of state-initiated force, such as businesses who receive grants and subsidies. He proposes that businesses who receive at least 50% of their funding from the state be confiscated by the workers. He says, "What we libertarians object to, then, is not government per se but crime, what we object to is unjust or criminal property titles; what we are for is not "private" property per se but just, innocent, non-criminal private property." Likewise, Karl Hess says, "libertarianism wants to advance principles of property but that it in no way wishes to defend, willy nilly, all property which now is called private...Much of that property is stolen. Much is of dubious title. All of it is deeply intertwined with an immoral, coercive state system."[24] By accepting an axiomatic definition of private property and property rights, anarcho-capitalists deny the legitimacy of a state on principle:

- "For, apart from ruling out as unjustified all activities such as murder, homicide, rape, trespass, robbery, burglary, theft, and fraud, the ethics of private property is also incompatible with the existence of a state defined as an agency that possesses a compulsory territorial monopoly of ultimate decision-making (jurisdiction) and/or the right to tax."[22]

Common property

Though anarcho-capitalists assert a right to private property, some anarcho-capitalists also point out that common property can exist by right in an anarcho-capitalist system. Just as an individual comes to own that which was unowned by mixing his labor with it or using it regularly, many people can come to own a thing in common by mixing their labor with it collectively, meaning that no individual may appropriate it as his own. This may apply to roads, parks, rivers, and portions of oceans.[25] Anarcho-capitalist theorist Roderick Long gives the following example:

- "Consider a village near a lake. It is common for the villagers to walk down to the lake to go fishing. In the early days of the community it's hard to get to the lake because of all the bushes and fallen branches in the way. But over time the way is cleared and a path forms - not through any coordinated efforts, but simply as a result of all the individuals walking by that way day after day. The cleared path is the product of labor - not any individual's labor, but all of them together. If one villager decided to take advantage of the now-created path by setting up a gate and charging tolls, he would be violating the collective property right that the villagers together have earned."[26]

Nevertheless, since property which is owned collectively tends to lose the level of accountability found in individual ownership to the extent of the number of owners - or make such accountability proportionately more complex, anarcho-capitalists generally distrust and seek to avoid intentional communal arrangements. Air, water, and land pollution, for example, are seen as the result of collectivization of ownership. Central governments generally strike down individual or class action censure of polluters in order to benefit "the many". Legal and economic subsidy of heavy industry is justified by many politicians for job creation, for example.

Anarcho-capitalists tend to concur with free-market environmentalists regarding the environmentally destructive tendencies of the state and other communal arrangements. Privatization, decentralization, and individualization are anarcho-capitalist goals. But in some cases, they not only provide a challenge, but are considered impossible. Established ocean routes provide an example of common property generally seen as difficult for private appropriation.

The contractual society

The society envisioned by anarcho-capitalists has been called the Contractual Society — "... a society based purely on voluntary action, entirely unhampered by violence or threats of violence."[23] — in which anarcho-capitalists claim the system relies on voluntary agreements (contracts) between individuals as the legal framework. It is difficult to predict precisely what the particulars of this society will look like because of the details and complexities of contracts.

One particular ramification is that transfer of property and services must be considered voluntary on the part of both parties. No external entities can force an individual to accept or deny a particular transaction. An employer might offer insurance and death benefits to same-sex couples; another might refuse to recognize any union outside his or her own faith. Individuals are free to enter into or reject contractual agreements as they see fit.

One social structure that is not permissible under anarcho-capitalism is one that attempts to claim greater sovereignty than the individuals that form it. The state is a prime example, but another is the current incarnation of the corporation — defined as a legal entity that exists under a different legal code than individuals as a means to shelter the individuals who own and run the corporation from possible legal consequences of acts by the corporation. It is worth noting that Rothbard allows a narrower definition of a corporation: "Corporations are not at all monopolistic privileges; they are free associations of individuals pooling their capital. On the purely free market, such men would simply announce to their creditors that their liability is limited to the capital specifically invested in the corporation ...."[23] However, this is a very narrow definition that only shelters owners from debt by creditors that specifically agree to the arrangement; it also does not shelter other liability, such as from malfeasance or other wrongdoing.

There are limits to the right to contract under some interpretations of anarcho-capitalism. Rothbard himself asserts that the right to contract is based in inalienable human rights[18] and therefore any contract that implicitly violates those rights can be voided at will, which would, for instance, prevent a person from permanently selling himself or herself into unindentured slavery. Other interpretations conclude that banning such contracts would in itself be an unacceptably invasive interference in the right to contract.[27]

Included in the right of contract is the right to contract oneself out for employment by others. Unlike anarcho-communists, anarcho-capitalists support the liberty of individuals to be self-employed or to contract to be employees of others, whichever they prefer and the freedom to pay and receive wages. David Friedman has expressed preference for a society where "almost everyone is self-employed" and "instead of corporations there are large groups of entrepreneurs related by trade, not authority. Each sells not his time, but what his time produces."[28] Rothbard does not express a preference either way but justifies employment as a natural occurrence in a free market that is not immoral in any way.

Law and order and the use of violence

Different anarcho-capitalists propose different forms of anarcho-capitalism, and one area of disagreement is in the area of law. Morris and Linda Tannehill, in The Market for Liberty, object to any statutory law whatsoever. They assert that all one has to do is ask if one is aggressing against another (see tort and contract law) in order to decide if an act is right or wrong.[29] However, Murray Rothbard, while also supporting a natural prohibition on force and fraud, supports the establishment of a mutually agreed-upon centralized libertarian legal code which private courts would pledge to follow. Such a code for Internet commerce, called The Common Economic Protocols was developed by Andre Goldman.

Unlike both the Tannehills and Rothbard who see an ideological commonality of ethics and morality as a requirement, David Friedman proposes that "the systems of law will be produced for profit on the open market, just as books and bras are produced today. There could be competition among different brands of law, just as there is competition among different brands of cars."[30] Friedman says whether this would lead to a libertarian society "remains to be proven." He says it is a possibility that very unlibertarian laws may result, such as laws against drugs. But, he thinks this would be rare. He reasons that "if the value of a law to it supporters is less than its cost to its victims, that law...will not survive in an anarcho-capitalist society."[31]

Anarcho-capitalists only accept collective defense of individual liberty (i.e., courts, military or police forces) insofar as such groups are formed and paid for on an explicitly voluntary basis. But, their complaint is not just that the state's defensive services are funded by taxation but that the state assumes it is the only legitimate practitioner of physical force. That is, it forcibly prevents the private sector from providing comprehensive security, such as a police, judicial, and prison systems to protect individuals from aggressors. Anarcho-capitalists believe that there is nothing morally superior about the state which would grant it, but not private individuals, a right to use physical force to restrain aggressors. Thus, if competition in security provision were allowed to exist, prices would be lower and services would be better according to anarcho-capitalists. According to Molinari, "Under a regime of liberty, the natural organization of the security industry would not be different from that of other industries."[32] Proponents point out that private systems of justice and defense already exist, naturally forming where the market is allowed to compensate for the failure of the state: private arbitration, security guards, neighborhood watch groups, and so on.[33] These private courts and police are sometimes referred to generically as Private Defense Agencies (PDAs).

The defense of those unable to pay for such protection might be financed by charitable organizations relying on voluntary donation rather than by state institutions relying on coercive taxation, or by cooperative self-help by groups of individuals.[34]

Like classical liberalism, and unlike anarcho-pacifism, anarcho-capitalism permits the use of force, as long as it is in the defense of persons or property. The permissible extent of this defensive use of force is an arguable point among anarcho-capitalists. Retributive justice, meaning retaliatory force, is often a component of the contracts imagined for an anarcho-capitalist society. Some believe prisons or indentured servitude would be justifiable institutions to deal with those who violate anarcho-capitalist property relations, while others believe exile or forced restitution are sufficient.[35]

One difficult application of defensive aggression is the act of revolutionary violence against tyrannical regimes. Many anarcho-capitalists admire the American Revolution as the legitimate act of individuals working together to fight against tyrannical restrictions of their liberties. In fact, according to Murray Rothbard, the American Revolutionary War was the only war involving the United States that could be justified.[36] Anarcho-capitalists, i.e. Samuel Edward Konkin III also feel that violent revolution is counter-productive and prefer voluntary forms of economic secession to the extent possible.

History and influences

Classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is the primary influence with the longest history on anarcho-capitalist theory. Classical liberals have had two main themes since John Locke first expounded the philosophy: the liberty of man, and limitations of state power. The liberty of man was expressed in terms of natural rights, while limiting the state was based (for Locke) on a consent theory.

In the 19th century, classical liberals led the attack against statism. One notable was Frederic Bastiat (The Law), who wrote, "The state is the great fiction by which everybody seeks to live at the expense of everybody else." Henry David Thoreau wrote, "I heartily accept the motto, 'That government is best which governs least'; and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe, 'That government is best which governs not at all'; and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have."[37]

The early liberals believed that the state should confine its role to protecting individual liberty and property, and opposed all but the most minimal economic regulations. The "normative core" of classical liberalism is the idea that in an environment of laissez-faire, a spontaneous order of cooperation in exchanging goods and services emerges that satisfies human wants.[38] Some individualists came to realize that the liberal state itself takes property forcefully through taxation in order to fund its protection services, and therefore it seemed logically inconsistent to oppose theft while also supporting a tax-funded protector. So, they advocated what may be seen as classical liberalism taken to the extreme by only supporting voluntarily funded defense by competing private providers. One of the first liberals to discuss the possibility of privatizing protection of individual liberty and property was France's Jakob Mauvillon in the 18th century. Later, in the 1840s, Julius Faucher and Gustave de Molinari advocated the same. Molinari, in his essay The Production of Security, argued, "No government should have the right to prevent another government from going into competition with it, or to require consumers of security to come exclusively to it for this commodity." Molinari and this new type of anti-state liberal grounded their reasoning on liberal ideals and classical economics. Historian and libertarian Ralph Raico asserts what that these liberal philosophers "had come up with was a form of individualist anarchism, or, as it would be called today, anarcho-capitalism or market anarchism."[39] Unlike the liberalism of Locke, which saw the state as evolving from society, the anti-state liberals saw a fundamental conflict between the voluntary interactions of people — society — and the institutions of force — the State. This society versus state idea was expressed in various ways: natural society vs. artificial society, liberty vs. authority, society of contract vs. society of authority, and industrial society vs. militant society, just to name a few.[32] The anti-state liberal tradition in Europe and the United States continued after Molinari in the early writings of Herbert Spencer, as well as in thinkers such as Paul Émile de Puydt and Auberon Herbert.

Ulrike Heider, in discussing the "anarcho-capitalists family tree," notes Max Stirner as the "founder of individualist anarchism" and "ancestor of laissez-faire liberalism."[40] According to Heider, Stirner wants to "abolish not only the state but also society as an institution responsible for its members" and "derives his identity solely from property" with the question of property to be resolved by a 'war of all against all'." Stirner argued against the existence of the state in a fundamentally anti-collectivist way, to be replaced by a "Union of Egoists" but was not more explicit than that in his book The Ego and Its Own published in 1844.

Later, in the early 20th century, the mantle of anti-state liberalism was taken by the "Old Right". These were minarchist, antiwar, anti-imperialist, and (later) anti-New Dealers. Some of the most notable members of the Old Right were Albert Jay Nock, Rose Wilder Lane, Isabel Paterson, Frank Chodorov, Garet Garrett, and H. L. Mencken. In the 1950s, the new "fusion conservatism", also called "cold war conservatism", took hold of the right wing in the U.S., stressing anti-communism. This induced the libertarian Old Right to split off from the right, and seek alliances with the (now left-wing) antiwar movement, and to start specifically libertarian organizations such as the (U.S.) Libertarian Party.

Nineteenth century individualist anarchism in the United States

Rothbard was influenced by the work of the 19th-century American individualist anarchists[41] (who were also influenced by classical liberalism). The question of whether or not anarcho-capitalism is a form of individualist anarchism is controversial. * Rothbard said in 1965: "Lysander Spooner and Benjamin T. Tucker were unsurpassed as political philosophers and nothing is more needed today than a revival and development of the largely forgotten legacy they left to political philosophy." However, he thought they had a faulty understanding of economics. The 19th century individualists had a labor theory of value, as influenced by the classical economists, but Rothbard was a student of neoclassical economics which does not agree with the labor theory of value. So, Rothbard sought to meld 19th century individualists' advocacy of free markets and private defense with the principles of Austrian economics: "There is, in the body of thought known as 'Austrian economics', a scientific explanation of the workings of the free market (and of the consequences of government intervention in that market) which individualist anarchists could easily incorporate into their political and social Weltanschauung".[42] Rothbard held that the economic consequences of their political system they advocate would not result in an economy with people being paid in proportion to labor amounts, nor would profit and interest disappear as they expected. Tucker thought that unregulated banking and money issuance would cause increases in the money supply so that interest rates would drop to zero or near to it. Rothbard, disagreed with this, as he explains in The Spooner-Tucker Doctrine: An Economist's View. He says that first of all Tucker was wrong to think that that would cause the money supply to increase, because he says that the money supply in a free market would be self-regulating. If it were not, then inflation would occur, so it is not necessarily desirable to increase the money supply in the first place. Secondly, he says that Tucker is wrong to think that interest would disappear regardless, because people in general do not wish to lend their money to others without compensation so there is no reason why this would change just because banking was unregulated. Also, Tucker held a labor theory of value. As a result, he thought that in a free market that people would be paid in proportion to how much labor they exerted and that if they were not then exploitation or "usury" was taking place. As he explains in State Socialism and Anarchism, his theory was that unregulated banking would cause more money to be available and that this would allow proliferation of new businesses, which would in turn raise demand for labor. This led him to believe that the labor theory of value would be vindicated, and equal amounts of labor would receive equal pay. Again, as a neoclassical economist, Rothbard did not agree with the labor theory. He believed that prices of goods and services are proportional to marginal utility rather than to labor amounts in free market. And he did not think that there was anything exploitative about people receiving an income according to how much others subjectively value their labor or what that labor produces, even if it means people laboring the same amount receive different incomes.

Benjamin Tucker opposed vast concentrations of wealth, which he believed were made possible by government intervention and state protected monopolies. He believed the most dangerous state intervention was the requirement that individuals obtain charters in order to operate banks and what he believed to be the illegality of issuing private money, which he believed caused capital to concentrate in the hands of a privileged few which he called the "banking monopoly." He believed anyone should be able to engage in banking that wished, without requiring state permission, and issue private money. Though he was supporter of laissez-faire, late in life he said that State intervention had allowed some extreme concentrations of resources to such a degree that even if laissez-faire were instituted, it would be too late for competition to be able to release those resources (he gave Standard Oil as an example).[43] Anarcho-capitalists also oppose governmental restrictions on banking. They, like all Austrian economists, believe that monopoly can only come about through government intervention. Individualists anarchists have long argued that monopoly on credit and land interferes with the functioning of a free market economy. Although anarcho-capitalists disagree on the critical topics of profit, social egalitarianism, and the proper scope of private property, both schools of thought agree on other issues. Of particular importance to anarcho-capitalists and the individualists are the ideas of "sovereignty of the individual", a market economy, and the opposition to collectivism. A defining point that they agree on is that defense of liberty and property should be provided in the free market rather than by the State. Tucker said, "[D]efense is a service like any other service; that it is labor both useful and desired, and therefore an economic commodity subject to the law of supply and demand; that in a free market this commodity would be furnished at the cost of production; that, competition prevailing, patronage would go to those who furnished the best article at the lowest price; that the production and sale of this commodity are now monopolized by the State; and that the State, like almost all monopolists, charges exorbitant prices."[44] But, again, since anarcho-capitalists disagree with Tucker's labor theory of value, they disagree that free market competition would cause protection (or anything else) to be provided "at cost." Like the individualists, anarcho-capitalists believe that land may be originally appropriated by, and only by, occupation or use; however, most individualists believe it must continually be in use to retain title. Lysander Spooner was an exception from those who believed in the "occupation and use" theory, and believed in full private property rights in land, like Rothbard.[45]

The Austrian School

The Austrian School of economics was founded with the publication of Carl Menger's 1871 book Principles of Economics. Members of this school approach economics as an a priori system like logic or mathematics, rather than as an empirical science like geology. It attempts to discover axioms of human action (called "praxeology" in the Austrian tradition) and make deductions therefrom. Some of these praxeological axioms are:

- humans act purposefully;

- humans prefer more of a good to less;

- humans prefer to receive a good sooner rather than later; and

- each party to a trade benefits ex ante.

Even in the early days, Austrian economics was used as a theoretical weapon against socialism and statist socialist policy. Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, a colleague of Menger, wrote one of the first critiques of socialism ever written in his treatise The Exploitation Theory of Socialism-Communism. Later, Friedrich Hayek wrote The Road to Serfdom, asserting that a command economy destroys the information function of prices, and that authority over the economy leads to totalitarianism. Another very influential Austrian economist was Ludwig von Mises, author of the praxeological work Human Action.

Murray Rothbard, a student of Mises, is the man who attempted to meld Austrian economics with classical liberalism and individualist anarchism, and is credited with coining the term "anarcho-capitalism". He wrote his first paper advocating "private property anarchism" in 1949, and later came up with the alternative name "anarcho-capitalism." He was probably the first to use "libertarian" in its current (U.S.) pro-capitalist sense. He was a trained economist, but also knowledgeable in history and political philosophy. When young, he considered himself part of the Old Right, an anti-statist and anti-interventionist branch of the U.S. Republican party. When interventionist cold warriors of the National Review, such as William Buckley, gained influence in the Republican party in the 1950s, Rothbard quit that group and formed an alliance with left-wing antiwar groups, noting an antiwar tradition among a number of self-styled left-wingers and to a degree closer to the Old Right conservatives. He believed that the cold warriors were more indebted in theory to the left and imperialist progressives, especially in regards to Trotskyist theory.".[46] Later, Rothbard was a founder of the U.S. Libertarian Party. In the late 1950s, Rothbard was briefly involved with Ayn Rand's Objectivism, but later had a falling out. Rothbard's books, such as Man, Economy, and State, Power and Market, The Ethics of Liberty, and For a New Liberty, are considered by some to be classics of natural law libertarian thought.

Historical precedents for anarcho-capitalism

To the extent that anarcho-capitalism is thought of as a theory or ideology—rather than a social process—critics say that it is unlikely ever to be more than a utopian ideal. Some, however, point to actual situations where protection of individual liberty and property has been voluntarily funded rather than being provided by a state through taxation.

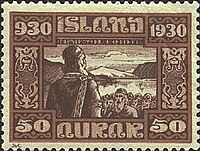

Medieval Iceland

According to David Friedman, "Medieval Icelandic institutions have several peculiar and interesting characteristics; they might almost have been invented by a mad economist to test the lengths to which market systems could supplant government in its most fundamental functions."[47] While not directly labeling it anarcho-capitalist, he argues that the Icelandic Commonwealth between 930 and 1262 had "some features" of an anarcho-capitalist society — while there was a single legal system, enforcement of law was entirely private and highly capitalist; and so provides some evidence of how such a society would function. "Even where the Icelandic legal system recognized an essentially "public" offense, it dealt with it by giving some individual (in some cases chosen by lot from those affected) the right to pursue the case and collect the resulting fine, thus fitting it into an essentially private system."[47]

The American Old West

According to the research of Terry L. Anderson and P. J. Hill, the Old West in the United States in the period of 1830 to 1900 was similar to anarcho-capitalism in that "private agencies provided the necessary basis for an orderly society in which property was protected and conflicts were resolved," and that the common popular perception that the Old West was chaotic with little respect for property rights is incorrect.[48]

Theoretical variance among anarcho-capitalists

A notable dispute within the anarcho-capitalist movement concerns the question of whether anarcho-capitalist society is based on deontological or consequentialist ethics. Natural-law anarcho-capitalism (as advocated by Rothbard) holds that a universal system of rights can be derived from natural law based on the widespread acceptance of the ethic of reciprocity. Consequentialists, however, do not require a universal system, maintaining that rights are merely constructs that humans create through contracts and individual relationships, and social relation must be judged by their consequences for all parties concerned. This approach, which has been called the Chicago School version[49] is theorized by David D. Friedman. As a consequence, Rothbardian anarcho-capitalists lean toward libertarian political deactivism[clarification needed] while Friedmanites prefer polycentric law centered on tort and contract law.

In The Machinery of Freedom, Friedman describes an economic approach to anarcho-capitalist legal systems. His description differs with Rothbard's because it does not use moral arguments; specifically, it does not appeal to a theory of natural rights. In Friedman's work, the economic argument is sufficient to derive the principles of anarcho-capitalism. Private defense or protection agencies and courts not only defend legal rights but supply the actual content of these rights and all claims on the market. People will have the law system they pay for, and because of economic efficiency considerations resulting from individuals' utility functions, such law will tend to be libertarian in nature but will differ from place to place and from agency to agency depending on the tastes of the people who buy the law. Also unlike other anarcho-capitalists, most notably Rothbard, Friedman has never tried to deny the theoretical cogency of the neoclassical literature on "market failure," nor has he been inclined to attack economic efficiency as a normative benchmark.[33]

Anarcho-capitalism today

Besides the well-known David D. Friedman, many others carry on and evolve the anarcho-capitalist traditions. They include Randy Barnett, Ian Bernard, Walter Block, Per Bylund, Gene Callahan, Bryan Caplan, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Scott Horton, Penn Jillette, Stephan Kinsella, Roderick Long, Carlo Lottieri, Wendy McElroy, Stefan Molyneux, Robert P. Murphy, Jan Narveson, Justin Raimondo, Lew Rockwell, Joseph Salerno, Jeremy Sapienza, George H. Smith, Joseph Sobran, Mark Thornton, Jeffrey Tucker and Thomas Woods.

Criticisms of anarcho-capitalism

Criticisms of anarcho-capitalism fall into several categories: practical criticisms which claim that anarcho-capitalism is unworkable in practice; critiques that claim that capitalism requires a coercive state to exist and that a society can be anarchist or capitalist, but not both; general critiques of the morality of capitalism and liberalism, which also apply to anarcho-capitalism; and a utilitarian critique, which claims that anarcho-capitalism would not maximize utility.

Objectivists and others argue that an anarcho-capitalist society would degenerate into a "war of all against all". For example, Noam Chomsky says, "Anarcho-capitalism, in my opinion, is a doctrinal system which, if ever implemented, would lead to forms of tyranny and oppression that have few counterparts in human history."[50] Other critics argue that the free rider problem makes the provision of protection services in an anarcho-capitalist society impractical.

Another State would replace the first

Some argue that a private defense agency would inevitably gain a defense monopoly, or form a cartel with other PDAs, after achieving a level of popularity that would give it an edge over its competitors. Anarcho-capitalists dismiss this claim, citing the power of market competition as a check on monopoly, the defensive nature of private security, and the level of offensive force that is required to prevent competition. Moreover, the anarcho-capitalists further counter this claim by arguing that it only creates a circular and contradicting argument, in which it implicitly advocates a monopoly on force to stop a monopoly on force from arising.

On page 41 of The Market for Liberty, the Tannehills point out that "[Government] attracts the worst kind of men to its ranks, shackles progress, forces its citizens to act against their own judgment, and causes recurring internal and external strife by its coercive existence. In view of all this, the question becomes not, “Who will protect us from aggression?” but “Who will protect us from the governmental ‘protectors’?” The contradiction of hiring an agency of institutionalized violence to protect us from violence is even more foolhardy than buying a cat to protect one’s parakeet."[51]

Minarchist critics may argue that, if monopolies of force are inevitable, community-controlled monopolies are preferable to privately controlled ones. Anarchist critics of private defense agencies may state that community militias should exist alongside or instead of private defense agencies. Other critics, both anarchist and minarchist, argue that formal police forces, whether community controlled or privately controlled, have institutional flaws which informal defense arrangements do not.[52]

The Tannehills, however, maintain that no coercive monopoly of force can arise on a truly free market. They write on page 81 that "A private defense service company, competing in an open market, couldn’t use force to hold onto its customers—if it tried to compel people to deal with it, it would compel them to buy protection from its competitors and drive itself out of business. The only way a private defense service company can make money is by protecting its customers from aggression, and the profit motive guarantees that this will be its only function and that it will perform this function well."[53] They go on to write:

Private defense service employees would not have the legal immunity which so often protects governmental policemen. If they committed an aggressive act, they would have to pay for it, just the same as would any other individual. A defense service detective who beat a suspect up wouldn’t be able to hide behind a government uniform or take refuge in a position of superior political power. Defense service companies would be no more immune from having to pay for acts of initiated force and fraud than would bakers or shotgun manufacturers. (For full proof of this statement, see Chapter 11.) Because of this, managers of defense service companies would quickly fire any employee who showed any tendency to initiate force against anyone, including prisoners. To keep such an employee would be too dangerously expensive for them. A job with a defense agency wouldn’t be a position of power over others, as a police force job is, so it wouldn't attract the kind of people who enjoy wielding power over others, as a police job does. In fact, a defense agency would be the worst and most dangerous possible place for sadists! Government police can afford to be brutal—they have immunity from prosecution in all but the most flagrant cases, and their “customers” can’t desert them in favor of a competent protection and defense agency. But for a free-market defense service company to be guilty of brutality would be disastrous. Force—even retaliatory force—would always be used only as a last resort; it would never be used first, as it is by governmental police.[54]

Anarcho-capitalism and anarchism

Some scholars do not consider anarcho-capitalism to be a form of anarchism, while others do. Some anarchists argue that anarcho-capitalism is not a form of anarchism due to their belief that capitalism is inherently authoritarian. In particular they argue that certain capitalist transactions are not voluntary, and that maintaining the capitalist character of a society requires coercion, which is incompatible with an anarchist society. Moreover, capitalistic market activity is essentially dependent on the imposition of private ownership and a particular form of exchange of goods where selling and buying is usually mandatory (due to the division of ownership of the capital, and consequently, value).

On the other hand, anarcho-capitalists such as Per Bylund, webmaster of the anarchism without adjectives website anarchism.net, note that the disconnect among non-anarcho-capitalist anarchists is likely the result of an "unfortunate situation of fundamental misinterpretation of anarcho-capitalism." Bylund asks, "How can one from this historical heritage claim to be both anarchist and advocate of the exploitative system of capitalism?" and answers it by pointing out that "no one can, and no one does. There are no anarchists approving of such a system, even anarcho-capitalists (for the most part) do not."[55] Bylund explains this as follows:

Capitalism in the sense of wealth accumulation as a result of oppressive and exploitative wage slavery must be abandoned. The enormous differences between the wealthy and the poor do not only cause tensions in society or personal harm to those exploited, but is essentially unjust. Most, if not all, property of today is generated and amassed through the use of force. This cannot be accepted, and no anarchists accept this state of inequality and injustice.

As a matter of fact, anarcho-capitalists share this view with other anarchists. Murray N. Rothbard, one of the great philosophers of anarcho-capitalism, used a lot of time and effort to define legitimate property and the generation of value, based upon a notion of “natural rights” (see Murray N. Rothbard’s The Ethics of Liberty). The starting point of Rothbard’s argumentation is every man’s sovereign and full right to himself and his labor. This is the position of property creation shared by both socialists and classical liberals, and is also the shared position of anarchists of different colors. Even the statist capitalist libertarian Robert Nozick claimed contemporary property was unjustly accrued and that a free society, to him a “minimalist state,” needs to make up with this injustice (see Robert Nozick’s “Anarchy, State, Utopia”).

Thus it seems anarcho-capitalists agree with Proudhon in that “property is theft,” where it is acquired in an illegitimate manner. But they also agree with Proudhon in that “property is liberty” (See Albert Meltzer’s short analysis of Proudhon’s “property is liberty” in Anarchism: Arguments For and Against, p. 12-13) in the sense that without property, i.e. being robbed of the fruits of one’s actions, one is a slave. Anarcho-capitalists thus advocate the freedom of a stateless society, where each individual has the sovereign right to his body and labor and through this right can pursue his or her own definition of happiness.[55]

Murray N. Rothbard notes that the capitalist system of today is, indeed, not properly anarchistic because it is so often in collusion with the state. According to Rothbard, "what Marx and later writers have done is to lump together two extremely different and even contradictory concepts and actions under the same portmanteau term. These two contradictory concepts are what I would call 'free-market capitalism' on the one hand, and 'state capitalism' on the other."[56]

"The difference between free-market capitalism and state capitalism," writes Rothbard, "is precisely the difference between, on the one hand, peaceful, voluntary exchange, and on the other, violent expropriation." He goes on to point out that he is "very optimistic about the future of free-market capitalism. I’m not optimistic about the future of state capitalism—or rather, I am optimistic, because I think it will eventually come to an end. State capitalism inevitably creates all sorts of problems which become insoluble."[57]

Murray Rothbard maintain that anarcho-capitalism is the only true form of anarchism[58] – the only form of anarchism that could possibly exist in reality, as, he argues, any other form presupposes an authoritarian enforcement of political ideology (redistribution of private property, etc). In short, while granting that certain non-coercive hierarchies will exist under an anarcho-capitalist system, they will have no real authority except over their own property: a worker existing within such a 'hierarchy' (answerable to management, bosses, etc) is free at all times to abandon this voluntary 'hierarchy' and 1) create an organization within which he/she is at (or somewhere near) the top of the 'hierarchy' (entrepreneurship), 2) join an existing 'hierarchy' (wherein he/she will likely be lower in the scheme of things), or 3) abandon these hierarchies altogether and join/form a non-hierarchical association such as a cooperative, commune, etc. Since there will be no taxes, such cooperative organizations (labour unions, communes, voluntary socialist associations wherein the product of the labour and of the capital goods of those who join which they were able to peaceably acquire would be shared amongst all who joined, etc) would, under anarcho-capitalism, enjoy the freedom to do as they please (provided, of course that they set up their operation on their own -or un-owned- property, in other words so long as they do so without force).

According to this argument, the free market is simply the natural situation that would result from people being free from authority, and entails the establishment of all voluntary associations in society: cooperatives, non-profit organizations (which would, just as today, be funded by individuals for their existence), businesses, etc. (in short, a free market does not equal the end of civil society, which continues to be a -rather bizarre- critique of anarcho-capitalism). Moreover, anarcho-capitalists (as well as classical liberal minarchists and others) argue that the application of so-called "leftist" anarchist ideals (e.g. the forceful redistribution of wealth from one set of people to another) requires an authoritarian body of some sort that will impose this ideology. (Voluntaryist socialism, of course, is completely compatible with anarcho-capitalism.) Some also argue that human beings are motivated primarily by the fulfillment of their own needs and wants. Thus, to forcefully prevent people from accumulating private capital, which could result in further fulfillment of human desires, there would necessarily be a redistributive organization of some sort which would have the authority to, in essence, exact a tax and re-allocate the resulting resources to a larger group of people. This body would thus inherently have political power and would be nothing short of a state. The difference between such an arrangement and an anarcho-capitalist system is precisely the voluntary nature of organization within anarcho-capitalism contrasted with a centralized ideology and a paired enforcement mechanism which would be necessary under a coercively 'egalitarian'-anarchist system.

Stability of anarcho-capitalist legal institutions

Two of the more prominent academics who have given some serious thought to essentially anarcho-capitalist legal institutions are Richard Posner, who is now a Federal Appeals Judge and a prolific legal scholar, and economist William Landes. In their 1975 paper "The Private Enforcement of Law",[59] they discuss a previous gedankenexperiment undertaken by Becker and Stigler in which it was proposed that law enforcement could be privatized, and they explain why they believe such a system would not be economically efficient. According to David D. Friedman's later rebuke "Efficient Institutions for the Private Enforcement of Law",[60]

[Landes and Posner argued] that the private system has essential flaws that make it inferior to an ideal public system except for offenses that can be detected and punished at near zero cost. They concede that the private system might still be preferable to the less than ideal public system that we observe. However they argue that the prevalence of private enforcement for offenses that are easily detected (most civil offenses) and its rarity for offenses that are difficult to detect (most criminal offenses) suggest that our legal system is, at least in broad outline, efficient, using in each case the most efficient system of enforcement.

Friedman, however, proceeds to argue that "the inefficiency Landes and Posner have demonstrated in the particular private enforcement institutions they describe can be eliminated by minor changes in the institutions."

The label "anarcho-capitalism"

As aforementioned in this article, the label "anarcho-capitalism" was formulated by Murray Rothbard, the father of the ideology. However, some anarcho-capitalists cite reservations pertaining to such a label, since they find it to be misleading. Such concerns relate to the nature of the word "anarchy". Everyday people commonly equate anarchy with chaos. Evidently, anarcho-capitalists do believe in an orderly society and have never advocated a state of chaos or anomie. Nevertheless, the average Joe is not schooled in political philosophy or science. Thus, he or she cannot help but link anarchy with disorder (even though no branch of anarchist thought has ever put forward anomie as the basis of social dealings).

In consequence, a number of anarcho-capitalists are seeking to devise new labels for their ideology, in order to avert the common misunderstanding within popular culture. Ian Bernard, one of the hosts of the American libertarian talk-radio show "Free Talk Live", uses the term "free marketeer" as a synonym for anarcho-capitalism. Other anarcho-capitalists use the phrase "voluntaryist" to describe their beliefs, since the ideal of voluntary human associations is at the root of anarcho-capitalist thinking.

Such moves by anarcho-capitalists are commonly undertaken to facilitate better outreach. This is considered of consequence since everyday people seldom question the legitimacy of governmental powers, and thus whether a government truly possesses any right to assume power over an individual. In his regular podcast "Freedomain Radio", the Canadian market anarchist philosopher Stefan Molyneux has suggested that anarcho-capitalists (and libertarians in general) demonstrate empathy with those one talks to about anarcho-capitalist tenets [61] . Accordingly, a re-labelling of the name of the ideology is an extension of such a feeling.

Anarcho-capitalist literature

Nonfiction

The following is a partial list of notable nonfiction works discussing anarcho-capitalism.

- Murray Rothbard founder of anarcho-capitalism:

- [10] Man, Economy, and State Austrian micro– and macroeconomics,

- Power and Market Classification of State economic interventions,

- The Ethics of Liberty Moral justification of a free society

- For a New Liberty An outline of how an anarcho-capitalist society could work

- Frederic Bastiat, The Law Radical classical liberalism

- Bruce L. Benson: The Enterprise of Law: Justice Without The State

- Bruce L. Benson: To Serve and Protect: Privatization and Community in Criminal Justice

- Davidson & Rees-Mogg, The Sovereign Individual Historians look at technology & implications

- David D. Friedman, The Machinery of Freedom Classic consequentialist defense of anarchism

- Auberon Herbert, The Right and Wrong of Compulsion by the State

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe, The Economics and Ethics of Private Property

- Albert Jay Nock, Our Enemy the State Oppenheimer's thesis applied to early US history

- Juan Lutero Madrigal, anarcho-capitalism: principles of civilization An anarcho-capitalist primer

- Stefan Molyneux, Universally Preferable Behavior, [[11]]'

- Franz Oppenheimer, The State Analysis of State; political means vs. economic means

- Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia Academic philosopher on libertarianism

- Herbert Spencer, Social Statics Includes the essay "The Right to Ignore the State"

- Linda and Morris Tannehill, The Market for Liberty Classic on Private defense agencies

- George H Smith, Justice Entrepreneurship in a Free Market Examines the Epistemic and entrepreneurial role of Justice agencies.

Fiction

Anarcho-capitalism has been examined in certain works of literature, particularly science fiction. An early example is Robert A. Heinlein's 1966 novel The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, in which he explores what he terms "rational anarchism".

In The Illuminatus! Trilogy by Robert Anton Wilson the Discordian Society headed by the character Hagbard Celine is anarcho-capitalist. The manifesto of the society in the novel 'Never Whistle While You're Pissing' contains Celine's Laws, three laws regarding government and social interaction.

Cyberpunk and postcyberpunk authors have been particularly fascinated by the idea of the break-down of the nation-state. Several stories of Vernor Vinge, including Marooned in Realtime, feature anarcho-capitalist societies, often portrayed in a favorable light. Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash and The Diamond Age, Max Barry's Jennifer Government, Cory Doctorow's Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom, and L. Neil Smith's The Probability Broach all explore anarcho-capitalist ideas. The cyberpunk portrayal of anarchy varies from the downright grim to the cheerfully optimistic, and it need not imply anything specific about the writer's political views. Neal Stephenson, in particular, refrains from sweeping political statements when deliberately provoked.[62][63]

Ken MacLeod's Fall Revolution series explores the future consequences of the breakdown of current political systems within a revolutionary context. The second novel of the series The Stone Canal deals specifically with an anarcho-capitalist society and explores issues of self-ownership, privatization of police and courts of law, and the consequences of a contractual society.

In Matt Stone's (Richard D. Fuerle) novelette On the Steppes of Central Asia[64] an American grad student is invited to work for a newspaper in Mongolia, and discovers that the Mongolian society is indeed stateless in a semi-anarcho-capitalist way. The novelette was originally written to advertise Fuerle's 1986 economics treatise The Pure Logic of Choice[65].

See also

Template:Anarchism portal Template:MultiCol

- Schools of thought

- Agorism

- Autarchism

- Crypto-anarchism

- Kritarchy

- Left-rothbardianism

- Market populism

- anarcho-syndicalism

| class="col-break " |

- Concepts

Citations

- ^ Robert P. Murphy. "What Are You Calling 'Anarchy'?".

- ^ Adams, Ian. 2002. Political Ideology Today. p. 135. Manchester University Press; Ostergaard, Geoffrey. 2003. Anarchism. In W. Outwaite (Ed.), The Blackwell Dictionary of Modern Social Thought. p. 14. Blackwell Publishing

- ^ Hess, Karl. The Death of Politics. Interview in Playboy Magazine, March 1969

- ^ Holcombe, Randall G., Common Property in Anarcho-Capitalism, Journal of Libertarian Studies, Volume 19, No. 2 (Spring 2005):3–29.

- ^ libertarianism. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 30 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://search.eb.com/eb/article-234237

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N., Future of Peace and Capitalism; Murray N. Rothbard, and Right: The Prospects for Liberty.

- ^ Adams, Ian. Political Ideology Today. Manchester University Press 2001. p. 33

- ^ "A student and disciple of the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises, rothbard combined the laissez-faire economics of his teacher with the absolutist views of human rights and rejection of the state he had absorbed from studying the individualist American anarchists of the nineteenth century such as Lysander Spooner and Benjamin Tucker." Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought, 1987, ISBN 0-631-17944-5, p. 290

- ^ Rothbard, Murray. For A New Liberty. 12 The Public Sector, III: Police, Law, and the Courts

- ^ Friedman, David. The Machinery of Freedom. Second edition. La Salle, Ill, Open Court, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Friedman, David D. The Machinery of Freedom. Chapter 42

- ^ Hans-Hermann Hoppe "Argumentation Ethics" Retrieved 6 February 2007

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N. (1988) "What's Wrong with Liberty Poll; or, How I Became a Libertarian", Liberty, July 1988, p.53

- ^ Andrew Rutten. "Can Anarchy Save Us from Leviathan?" in The Independent Review vol. 3 nr. 4 p. 581. [1] [2] "He claims that the only consistent liberal is an anarcho-liberal."

- ^ "Murray N. Rothbard (1926–1995), American economist, historian, and individualist anarchist." Avrich, Paul. Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America, Abridged Paperback Edition (1996), p. 282 "Although there are many honorable exceptions who still embrace the "socialist" label, most people who call themselves individualist anarchists today are followers of Murray Rothbard's Austrian economics, and have abandoned the labor theory of value." Carson, Kevin. Mutualist Political Economy, Preface.

- ^ a b c d e Hoppe, Hans-Hermann (2001)"Anarcho-Capitalism: An Annotated Bibliography" Retrieved 23 May 2005

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N. (1982) "Law, Property Rights, and Air Pollution" Cato Journal 2, No. 1 (Spring 1982): pp. 55–99. Retrieved 20 May 2005

- ^ a b c Rothbard, Murray N. (1982) The Ethics of Liberty Humanities Press ISBN 0-8147-7506-3:p162 Retrieved 20 May 2005

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N. (1973) For a new Liberty Collier Books, A Division of Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., New York: pp.24–25. Retrieved 20 May 2005

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N. (1975) Society Without A State (pdf) Libertarian Forum newsletter (January 1975)

- ^ Exclusive Interview With Murray Rothbard The New Banner: A Fortnightly Libertarian Journal (25 February 1972)

- ^ a b Hoppe, Hans-Hermann (2002) "Rothbardian Ethics" Retrieved 23 May 2005

- ^ a b c Rothbard, Murray N. (1962) [3] Man, Economy & State with Power and Market Ludwig von Mises Institute ISBN 0-945466-30-7 ch2 Retrieved 19 May 2005

- ^ Hess, Karl (1969) Letter From Washington The Libertatian Forum Vol. I, No. VI (June 15 1969) Retrieved 5 August 2006

- ^ Holcombe, Randall G., Common Property in Anarcho-Capitalism, Journal of Libertarian Studies, Volume 19, No. 2 (Spring 2005):3–29.

- ^ Long, Roderick T. 199. "A Plea for Public Property." Formulations 5, no. 3 (Spring)

- ^ Nozick, Robert (1973) Anarchy, State, and Utopia

- ^ Friedman, David. The Machinery of Freedom: Guide to a Radical Capitalism. Harper & Row. pp. 144–145

- ^ Brown, Susan Love, The Free Market as Salvation from Government: The Anarcho-Capitalist View, Meanings of the Market: The Free Market in Western Culture, edited by James G. Carrier, Berg/Oxford, 1997, p. 113.

- ^ Friedman, David. The Machinery of Freedom. Second edition. La Salle, Ill, Open Court, pp. 116–117.

- ^ ibid pp. 127–128

- ^ a b Molinari, Gustave de (1849) The Production of Security (trans. J. Huston McCulloch) Retrieved 15 July 2006

- ^ a b Friedman, David D. (1973) The Machinery of Freedom: Guide to a Radical Capitalism Harper & Row ISBN 0-06-091010-0 ch29

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N. (1973) For a new Liberty Collier Books, A Division of Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., New York: pp.223. Retrieved 5 August 2006

- ^ O'Keeffe, Matthew (1989) "Retribution versus Restitution" Legal Notes No.5, Libertarian Alliance ISBN 1-870614-22-4 Retrieved 19 May 2005

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N. (1973) Interview Reason February 1973, Retrieved 10 August 2005

- ^ Thoreau, Henry David (1849) Civil Disobedience

- ^ Razeen, Sally. Classical Liberalism and International Economic Order: Studies in Theory and Intellectual History, Routledge (UK) ISBN 0-415-16493-1, 1998, p. 17

- ^ Raico, Ralph (2004) Authentic German Liberalism of the 19th Century Ecole Polytechnique, Centre de Recherce en Epistemologie Appliquee, Unité associée au CNRS

- ^ Heider, Ulrike. Anarchism: Left, Right and Green, San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1994, pp. 95–96

- ^ "...only a few individuals like Murray Rothbard, in Power and Market, and some article writers were influenced by these men. Most had not evolved consciously from this tradition; they had been a rather automatic product of the American environment." DeLeon, David. The American as Anarchist: Reflections on Indigenous Radicalism. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978, p. 127

- ^ "The Spooner-Tucker Doctrine: An Economist's View", Journal of Libertarian Studies, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 7[4] (1965, 2000)

- ^ Tucker, Benjamin. State Socialism and Anarchism

- ^ Tucker, Benjamin. "Instead of a Book" (1893)

- ^ Watner, Carl. Spooner Vs. Liberty in The Libertarian Forum. March 1975. Volume VII, No 3. ISSN 0047-4517. pp. 5–6.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N. [5], Retrieved 10 September 2006

- ^ a b Friedman, David D. (1979) Private Creation and Enforcement of Law: A Historical Case, Retrieved 12 August 2005

- ^ Anderson, Terry L. and Hill, P. J. An American Experiment in Anarcho-Capitalism: The Not So Wild, Wild West, The Journal of Libertarian Studies

- ^ Tame, Chris R. October 1983. The Chicago School: Lessons from the Thirties for the Eighties. Economic Affairs. p. 56

- ^ Lane, Tom. "Noam Chomsky On Anarchism" Znet (1996)

- ^ Linda & Morris Tannehill. Market for Liberty (San Francisco: Fox & Wilkes, 1993), p. 41. Originally published 1970.

- ^ Malatesta, Errico, 1921, in a letter to Venturini.

- ^ Linda & Morris Tannehill. Market for Liberty, p. 81.

- ^ Linda & Morris Tannehill. Market for Liberty, p. 84.

- ^ a b Bylund, Per. Anarchism, Capitalism, and Anarcho-Capitalism, anarchism.net. July 6, 2004.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N. Future of Peace and Capitalism, James H. Weaver, ed., Modern Political Economy (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1973), pp. 419-430

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N. Exclusive Interview With Murray Rothbard. The New Banner: A Fortnightly Libertarian Journal. 25 February 1972.

- ^ William Landes and Richard Posner. "The Private Enforcement of Law." 4 Journal of Legal Studies 1. [6]

- ^ David D. Friedman. "Efficient Institutions for the Private Enforcement of Law." 13 Journal of Legal Studies 379. [7] [8]

- '^ Respecting the 'Sheeple article by Stefan Molyneux at Lew Rockwell.com [9]

- ^ Godwin, Mike (2005). "Neal Stephenson's Past, Present, and Future; The author of the widely praised Baroque Cycle on science, markets, and post-9/11 America" (print article). Reason (magazine). Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Roblimo (2004-10-20). "Neal Stephenson Responds With Wit and Humor" (email exchange). Slashdot. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "On the Steppes of Central Asia". Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ^ "The Pure Logic of Choice". Retrieved 2008-02-10.

References

- Bruce Benson: The Enterprise of Law: Justice Without The State

- Hart, David M.: Gustave de Molinari and the Anti-Statist Liberal Tradition Retrieved 14 September 2005

- Hoppe, Hans-Hermann: A Theory of Socialism and Capitalism

- Hoppe, Hans-Hermann: Democracy: The God That Failed

- Rothbard, Murray: For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto

- Rothbard, Murray: The Ethics of Liberty

- Spooner, Lysander: (1867) No Treason: The Constitution of No Authority Retrieved 19 May 2005

- Tannehill, Linda and Morris: The Market For Liberty

- Tucker, Benjamin: (1888) State Socialism and Anarchism:How Far They Agree, and Wherein They Differ Liberty 5.16, no. 120 (10 March 1888), pp. 2–3.Retrieved 20 May 2005

- Tucker, Benjamin: (1926) Labor and its Pay Retrieved 20 May 2005

Sources that consider anarcho-capitalism a form of anarchism

As a form of individualist anarchism

- Bottomore, Tom. Dictionary of Marxist Thought, Anarchism entry, p.21 1991

- Barry, Norman. Modern Political Theory, 2000, Palgrave, p. 70

- Adams, Ian. Political Ideology Today, Manchester University Press (2002) ISBN 0-7190-6020-6, p. 135

- Grant, Moyra. Key Ideas in Politics, Nelson Thomas 2003 ISBN 0-7487-7096-8, p. 91

- Heider, Ulrike. Anarchism:Left, Right, and Green, City Lights, 1994. p. 3.

- Ostergaard, Geoffrey. Resisting the Nation State - the anarchist and pacifist tradition, Anarchism As A Tradition of Political Thought. Peace Pledge Union Publications [12] ISBN 0902680358

- Avrich, Paul. Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America, Abridged Paperback Edition (1996), p. 282

- Brooks, Frank H. (ed) (1994) The Individualist Anarchists: An Anthology of Liberty (1881–1908), Transaction Publishers, Preface p. xi

- Tormey, Simon. Anti-Capitalism, One World, 2004, pp. 118–119

- Raico, Ralph. Authentic German Liberalism of the 19th Century, Ecole Polytechnique, Centre de Recherce en Epistemologie Appliquee, Unité associée au CNRS, 2004

- Offer, John. Herbert Spencer: Critical Assessments, Routledge (UK) (2000), p. 243

- Busky, Donald. Democratic Socialism: A Global Survey, Praeger/Greenwood (2000), p. 4

- Heywood, Andrew. Politics: Second Edition, Palgrave (2002), p. 61

Sources claiming that individualist anarchism was reborn as anarcho-capitalism

- Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought, 1991, ISBN 0-631-17944-5, p. 11

- Levy, Carl. Anarchism, Microsoft® Encarta® Online Encyclopedia 2006 [13] MS Encarta (UK).

As a form of anarchism in general

- Sylvan, Richard. Anarchism. A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy, editors Goodin, Robert E. and Pettit, Philip. Blackwell Publishing, 1995, p.231

- Perlin, Terry M. Contemporary Anarchism. Transaction Books, New Brunswick, NJ 1979, p. 7

- DeLeon, David. The American as Anarchist: Reflections of Indigenous Radicalism, Chapter: The Beginning of Another Cycle, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979, p. 117 & 123

- Brown, Susan Love, The Free Market as Salvation from Government: The Anarcho-Capitalist View, Meanings of the Market: The * Free Market in Western Culture, edited by James G. Carrier, Berg/Oxford, 1997, p. 99

- Kearney, Richard. Continental Philosophy in the 20th Century, Routledge (UK) (2003), p. 336

- Sargent, Lyman Tower. Extremism in America: A Reader, NYU Press (1995), p. 11

- Sanders, John T.; Narveson, For and Against the State, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 1996, ISBN 0-8476-8165-3 review

- Goodwin, Barbara. Using Political Ideas, fourth edition, John Wiley & Sons (1987), p. 137

Sources that do not consider anarcho-capitalism to be a form of anarchism

- Marshall, Peter. Demanding the Impossible, London: Fontana Press, 1992 (ISBN 0 00 686245 4) Chapter 38

- Eatwell, Roger. Wright, Anthony. Contemporary Political Ideologies (1999) ISBN 1855676060 p. 142

- Meltzer, Albert. Anarchism: Arguments For and Against AK Press, (2000) p.50

Further reading

- Murray Rothbard Father of modern anarcho-capitalism:

- Rothbard, Murray (1962). Man, Economy, and State; A Treatise on Economic Principles. Princeton, N.J.: Van Nostrand., A general book on Austrian economics.

- Rothbard, Murray (1970). Power & Market; Government and the Economy. Menlo Park, Calif.: Institute for Humane Studies., Classification of economic interventions by the state.

- Rothbard, Murray (2004). [[Man, economy, and state]] with [[Power and market]]: government and economy. Auburn, Ala.: Ludwig von Mises Institute. ISBN 0-945466-30-7.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - Rothbard, Murray (1978). For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto. New York, New York: Collier Books. ISBN 0-02-074690-3.

- Rothbard, Murray (1998) [1982]. The Ethics of Liberty. New York, New York: University Press. ISBN 0-8147-7506-3., Moral justification of a free society.

- Frederic Bastiat, The Law Radical classical liberalism

- Davidson & Rees-Mogg, The Sovereign Individual Historians look at technology & implications

- David D. Friedman, The Machinery of Freedom Classic utilitarian defense of anarchism

- Auberon Herbert, The Right and Wrong of Compulsion by the State

- Albert Jay Nock, Our Enemy the State Oppenheimer's thesis applied to early US history

- Juan Lutero Madrigal, anarcho-capitalism: principles of civilization An anarcho-capitalist primer (webbed)

- Franz Oppenheimer, The State Analysis of State; political means vs. economic means

- Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia Academic philosopher on libertarianism

- Herbert Spencer, Social Statics Includes the essay "The Right to Ignore the State"

- Morris and Linda Tannehill, The Market for Liberty Classic on private defense agencies (PDAs)

- Robert Paul Wolff, In Defense of Anarchism, influential defence of anarchism within contemporary analytical philosophy

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Anarcho-Capitalism: An Annotated Bibliography

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe, The Economics and Ethics of Private Property

External links

Anarcho-capitalist websites and articles

- Kent For Liberty: Anarcho-Capitalism/Radical Libertarianism at its Finest

- Ideas is David D. Friedman's blog.

- Free market alternatives to the state Libertarian Nation Foundation

- Strike The Root is an anarcho-capitalist website featuring essays, news, and a forum.

- anti-state.com, has one of the more active forums and infrequent theoretical and practical articles, and hosts Private Property Anarchists and Anarcho-Socialists: Can We Get Along? by Gene Callahan

- Simply Anarchy is an anarcho-capitalist website with articles, links and a forum

- The Molinari Institute offers online resources for those interested in exploring the ideas of Market Anarchism

- Ancapistan Network comes with an ancap start-up, articles and links

- Bertrand Lemennicier, a renowned French anarcho-capitalist economist

- Cuthhyra is a resource promoting anarcho-capitalism through essays, humour, quotes, links and more.

- Bryan Caplan's "Anarchism Theory FAQ" is written from the perspective of an anarcho-capitalist.

- Ludwig von Mises Institute is a research and educational center of classical liberalism; including anarcho-capitalism, libertarian political theory, and the Austrian School of economics.

- LewRockwell.com is a widely read anarcho-capitalist news site with the slogan "anti-state, anti-war, pro-market."

- Liberty Search, Specific search engine for classical liberalism and libertarianism

- A Legacy of Liberty and For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto by Murray N. Rothbard

- The American Experiment in Anarcho-Capitalism: The Not so Wild, Wild, West Anarcho-capitalism in the old "Wild West" in the U.S.

- The anarcho-capitalist political theory of Murray N. Rothbard in its historical and intellectual context by Roberta Modugno Crocetta

- Panarchy, another way of considering things that is considered by some ultimately equivalent to anarcho-capitalism.

- A Brief Introduction to Philosophical Anarchism from the viewpoint of an anarcho-capitalist

- Sovereign Life and Sovereign Individual at Sovereignlife.com

- Individualist Anarchist Society at UC Berkeley

- Anarcho-Capitalism Lifestyle guide for Anarcho-capitalists

- The liberal theory of power a solution to complete anarcho-capitalism

- Sumit Dahiya "The home of the Anti-Government Pro-Enterprise Movement of India"

- Freedomain Radio anarcho-capitalism podcast and message board (Stefan Molyneux)

- Free Talk Live Anarcho-capitalist podcast, message board, and nationally syndicated radio program