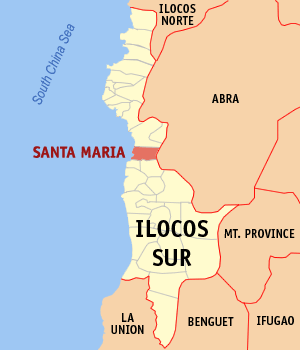

Santa Maria, Ilocos Sur

Santa Maria is a 3rd class municipality in the province of Ilocos Sur, Philippines. According to the 2000 census, it has a population of 26,396 people in 5,414 households.

Barangays

Santa Maria is politically subdivided into 33 barangays.

|

|

|

SANTA MARIA: THE FIRST 200 HUNDRED YEARS

It has been aptly said that if we are to know the present better and thus, effectively plan for the future, it is inescapable that we must look back to the past.

The remote past for Santa Maria is the nebulous, uncharted era long before the intrepid Spanish conquistador and the equally spirited missionary came, one in search of lands and gold for the king, the other in search of souls for

his King. Certainly, lands, gold and souls were to be found in the Ilocos, for even before Hispanic times, Ilocos was known to have been among the more populated regionn in the country, which traded gold with Chinese and Japanese merchants.

Ilocano, believed to have been of Malay origin, and the Isnegs and the Tinguians, who eventually populated the hinterlads of Ilocos, were the early inhabitants. These groups engaged in farming, fishing and to some extent, in weaving and pottery, and learned to control their environment - for even then the land lacked the fertility of Central Luzon, and the narrow strip, hemmed in by the China Sea to the west and the Cordillera mountain ranges to

the east, was oftened times visited by typhoons and droughts and, thus, bountiful harvests were exceptions rather than the rule.

The Ilocanos, then as now was also known for his religiousity, expressed in his worship of anitos, spirits and gods, the supreme god being Kabunian. Certain aspects of these early religious practice survive even today the term

buniag (ie baptism), it is said comes from Buni or Kabunian, and, until more recent years, in Santa Maria some professed belief in spirits inhibiting fields and trees, in whose honor half-cooked rice, bettle nut and chicken meat were offered.

These belief in spirits greatly helped the Spanish conquistador and the missionary who both came to Ilocos and

under whose joint efforts, the Ilocos was subsequently converted to Christianity and brought under Spanish rule. Juan De Salcedo, only twenty-two years old at the time and already a conqueror of the Tagalog, Zanbales and Central Luzon provinces, explored the Ilocos in order, he said, to define its boundaries and to discover a shorter

passage from there to Mexico. Sailing from Manila on May 20, 1575 he entered the Abra River on June 13, 1572 and directed his fleet to Vigan. That same year after exploring the Ilocos, he established an encomieda in Vigan,

thus formally subjecting the Ilocos to Spanish rule.

The complete subjection of the whole Ilocos region was a long, painful process, however, as most Ilocanos

did not readily accept the Spanish conquerors. In all instances the sword went hand in hand with the cross and as towns fell under Spain, parishes with resident missionaries were established. Due to inavailability of personnel - both military and religious visitas - actually places where chapels were built and service by resident priests from the parishes - were also established. These eventually became independent parishes as more priest became available.

When Narvacan became a parish on April 25, 1587, Santa Maria, together with San Esteban and Santiago, became

its visita. The date of Santa Maria's canonical erection as an independent parish, however, has still to be definitely ascertained, as evidence available to us are not in full agreement.

Galende, following earlier statements made by the Augustinian historian Juan de Medina, puts the foundation of

the town as 1765, the same year that the Augustinians also founded Caloocan. Other sources, like"The Mapa General

de Las Almas que administran los PP. Agustinos Calzados en estas Islas Filipinas", for both 1832 and 1845,

Fr. Salvador Font's "Memoria" to the Ministry of Overseas Affairs for 1892, and Buzeta y Bravo's "Diccionario Geografico-Estadistico-Historico de las Isla Filipinas" (published in Madrid in 1851), sources whichwe have consulted, list 1769 as the date of the foundation of the town. To compound the matter, the "Catholic Directory

of the Philippines" place the date as 1760, and as if that were not enough, the town celebrated last year (1967) the bicentenial of the town, on the strenght of a "Libro de Bautismos" for 1767, still preserved in the Parish

archives.

Another source which we consulted is the manuscript by the late Macario, whose sense of history is quite amazing. Unfortunately, Brilliantes failed to cite his sources, which would have facilitated the checking of his data.

We have, however, checked what he lists down as names of parish priests from 1762 downward - the implication is that

the town first began to have a parish priest of its own at that time - using what is generally considered an

authoritative sourse, i.e Fr. Agustin Maria de Castro's "Misioneros agustinos en el Extremo Oriente 1565-1780 (Osario Venerable), but we failed to find names of these priests.

The Brilliantes manuscript, thus, opens itself to suspicion as a historical document, and must therefore, be

used with extreme caution. Nevertheless, we found it most interesting in that it lists the names of parish priests and capitanes, municipal presidents and mayors of the town, and highlights of the town's history from 1762 up to

1942. Part of the reconstruction of Santa Maria's history in this present narration is based on the Brilliantes

manuscript, but we would like to make it of record that, until such definitive data are collected and collated into a continuous narrative, these data should be taken as tentative.

In the light of conflicting evidence we, therefore, offer the following for what it may be worth. If one

applies the principle that a ministry might have it's own minister before its recognition as independent parish

and later reverts to the status of a visita, then Santa Maria has been an independent ministry since 1760.

Santa Maria was recognized officially as ministry in1765 after which, due to lack of priests, it again became

a simple visita of Narvacan. In 1769, it again became an independent parish and since that time, has always had a

minister. There might have been baptism in the town before that time, of course, but the earliest record of

baptisms is dated 1767 and, therefore, it is not without reason that the town celebrated the 200th anniversary

of its Christianization in 1967.

Be that as it may, the town (situated on a plain near the coast, 124-3'30" longtitude to the east and 17-15'00" to the north, and bounded in the north by Narvacan, in the south by San Esteban, in the east by the Cordillera

range, and in the west by the China Sea) rose to prominence due to its proximity to interior settlements.

The Augustinian friar, Fr. Juan Cardeno, another varian of his name is Cordano, as it appears in certain sources,' who was Santa Maria's parish priests for fifty years, from October 27, 1805 to September 18, 1858,

shortly before his death, dedicated a lifetime helping the townspeople in their spiritual and material needs.

He negotiated the construction of a ditch which stretched a league to channel a river, thus assuring the

harvest of rice for all the people. The rise of Santa Maria to prominence did not only affect the interior

settlements but also the neighboring towns of San Esteban and Santiago which, though founded earlier, were later converted into a visita of Santa Maria in as late as 1800.

POPULATION. The rate of increase of population in Santa Maria was quite steady. In 1793, there were 834 inhabitants, making Santa Maria the No. 15 town in the whole Ilocos province. (Due to rapid increase of population, the province was divided into Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur in 1818, pursuant to a real cedula dated February 2,

1818). By 1803, it increased to 7,893; but by 1831 it decreased to 7,349 as a result of the cholera or other epidemics broke out.

In 1845, there were 10,908 inhabitants; in 1850 11,900; in 1866 12,059; and in 1880, 15,152. But the population diminished to 11,426 in 1892; and to 10,030 in 1901, possibly as a result of the cholera epidemics of 1881, 1883,

and 1889. Also, as a result of forced labor, some Santa Marians left the town and sought more congenial environments

in central Luzon, notably Cuyapo. It is almost certain that Central Luzon barrios taday named "Casantamarian" can be trace their origins to this time, when their original inhabitants immigrated from Santa Maria.

Through the years, Santa Maria's population has grown, as statistics found elsewhere in this volume would show, and this despite the more recent immigration of Santa Marians to Hawaii, California and Mindanao.

THE CHURCH AND CONVENT - The majestic church, convent and tower built atop a knoll, and with an air of a medieval cathedral-fortress about them, have definitely intrigued many, not the least of whom are present

writers.

Like most Philippine churches, legend has been associated with the Santa Maria church. It is said that the original chapel dedicated to the Blessed Virgin was built at a site in the present day barrio ofBulbullala. The statue of the virgin enthroned in that small chapel, so the legend goes, periodically disappeared and was always subsequently found on a guava tree at the site of the present main altar of the church.

Father Mariano Dacanay, the town's Ilokano parish priest from September 1, 1902 to May 27, 1922, has written

another variant to this legend which, he assures us, has been obtained from reliable sources. The virgin's statue, Fr. Dacanay relates, was enthroned in another church (not the chapel at Bulbullala) which used to be situated in the

present East Elementary School compound at the foot of the present East Elementary school compound at the foot

of the present church. It was from here, Fr. Dacanay adds, that the image made its peregrinations to that guava

tree on the knoll where the church now stands.

Legends about the virgin have indeed become part of Philippine religious lore, and, if these legends are

to be believed, the Virgin herself made known her preference for her permanent home. Almost invatiably a tree

is associated with this, and possibly among the most celebrated being that of the Nuestra Senora de Guia who

made known her wish by lodging on a pandaan tree on the site where the Ermita church now stands. Viewed againts

this backdrop, the Santa Maria legend about the Virgin is, thus, nothing extraordinary.

Be that as it may, a chapel and a tower were built in 1810. The records failed to specify what chapel

built at the present site of the church? Or was it actually the small church built on the present site of

the East Elementary School? To us, it would seem that the first case was more likely, as no tower, nor

even ruins of it, are found below the knoll. Thus, the legend, as recounted by Fr. Dacanay, makes more sense than the other one.

Records also show that the bells for the tower arrived in 1811. In 1822 the convent and church were razed to the ground (again, one is tempted to ask: Whichconvent and which church?). It seems likely that what is meant here were the convent and the church below the knoll.

Nevertheless, the zealous Fr. Bernardino Lago later made Santa Maria a center of his missionary activities for the interior settlements. This may, indeed, explain the (reconstructed?) huge church and convent, and the

presence of many side altars in church.. Thus, there seems reason to believe that newly arrived missionaries

learned Ilokano psychology and perfected their knowledge of the Ilokano language in Santa Maria before they were sent to neighboring mission posts. Or again, it appears possible that the convent provided a retreat

housefor weary Augustinian missionaries from their intense apostolic labors, and for sickly or aging friars.

Fr. Lago converted thousands which necessitated the establishment of the town of Nueva Coveta, the present town of Burgos, in 1831.

In 1863, the church was remodelled, and the sides of the knoll surrounding it, the convent and the tower,

reinforced with huge stone boulders kept in place by mortar, a task which must have taken a heavy toll, as it

lasted up to 1871. Thus, people began to react againts forced labor, and took no pain to hide it.

Obviously, the Santa Marians had not completely forgotten the Diego Silang rebellion in 1762 during the British

occupation, and which must have convinced them that the Spaniards were not invincible after all. They also must

not have easily forgotten the Sarrat rebellion in 1815, nor the more recent Cavite revolt headed by Camerino in

1869. For while it is true that communication was primitively slow (mails, however, were sent from, and received

in Santa Maria in as early as the 1850s), it is equally true that they received news from the outside world somehow or the other.

LIFE IN SANTA MARIA. Yet, Santa Maria had also known periods of serenity and more stable times, so well described by Manuel Buzeta and Felipe Bravo, from whom we lean heavily for the folowing description of the town.

In 1850, the town had some 1,983 houses, constructed like most Philippine house, some made of wood, most made of bamboo and cogoon grass. The more notable edifices were the tribunal, the-roofed and made of stone, on whose

ground floor is the prison. This building is located in the plaza near the market place, where vegetables, eggs, meat and fish are sold. Sometimes itinerant mestizos sold merchandise there.

In front of the tribunal stood three private houses, also tile-roofed and made of stone, as well as two others, of the same material, about to be finished. The town has a primary school maintained by the coffers of the town. Moreover, there are private schools for boys and girls.

The church and the tower are made of stone, and the sacristy, of stone and bricks. Near the church, atop

a knoll is the convent or the parish house, which is an equally imposing building. Down below, about 200 steps

away, is the cemetery with its well ventilated chapel, but which was destroyed by an earthquake not long ago.

In Santa Maria, mail is received from the north (from Narvacan) every Tuesday morning, and those from Manila,

through Santiago, every Thursday noon. The town consist of the barrios of Patac (Pacak?), in the south, and those of San Gelacio, San Ignacio, and San Francisco, which are all close enough to the church ("bajo la campana");

farther away are Tanggaoan, Silag, Minoric, Bitalag, Gusing, Subsubosob, Dingtan and Cabaritan, separated by wide

fields, but each of these barrios have only a few huts where the natives stay during harvest time.

The town has two ports, one in the west, capable of handling big ships, the other in the north, which can

handle only small boats because of its narrow entrance, but can be widened to accomodate bigger ships as it did

sometime in the past, whentwo full-rigged boats were constructed there.

The land is quite fertile, most of which is irrigated, thanks to the zeal of Fr. Juan Cordano, present (1850) parish priest, who, with the help of the colonial government was able to realize many improvements of the town, including the construction of an irrigation system, after six years of work. In 1804 when Cordano took over the parish, the harvests were always in the danger of being lost due to the lack of irrigation, thus, only 994 paid

tribute; now (1850) 2,586 do so.

The most important products are rice, wheat, cotton, indigo, sugar cane and corn. Corn is so abundant that it is exported to Santa, Bantay, Santa Catalina, San Vicente and many others. Oranges, Santol, many kinds of

bananas, pineapple and cacao are also grown in abundance.

In the mountains nearby are different kinds of wood, like narra, molave, banana, panurapin, bulala, and

others. Also found there are wild chickens, deer, and various varieties of birds. There is a gold mine in Pinsal,

which is still to be exploited.

The inhabitants engage in agriculture and lumbering, and the women in weaving cotton cloth, some of which are sold to other places.

OF TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS. thus, the people were seemingly satisfied, which followed its course in its slow, slackened pace. But resentment against the rulers began to pile up, although no rumblings were yet heard. Indeed, there is no evidence to show that Santa Marians resented either the construction of the irrigation system in 1813, or the fencing of the town in 1817, both during Fr. Cordano's time.

It is quite possible that forced labor was also used in town projects during Cordanos time, for this was the

standard practice not only Santa maria but also in every town in the archipelago. Forced labor, one is told, depleted manpower in many places, especially in areas where the male population were made to cut timber in forests,

or were made to work in shipyards, far from their own homes, and, thus, causing untold misery to their families.

There is no evidence to show that men from Santa Maria were dislocated to work in shipyards (although, as Buzeta and Bravo's narration would show, an attempt was made to build full-rigged boats there). Yet forced

labor, which no individual then as now would relish, became the order of the day. By 1881, according to records,

the Santa Marians became restless, who obviously resented working on these projects. Such resentment against the

Spanish ruler was expressed by Santa Marians who stoned the tribunal and, as the anonymouus chronicler states,

"they almost rose up in arms against the Spaniards."

Somehow or the other, no turbulent uprising resulted, and, if the natives harbored ill-feelings, they managed

to camouflage it even as they began construction of the municipal hall in 1883, obediently continuing its construction up to 1885, and even as they changed the roof of the church into galvanized iron.

Indeed, Santa Maria had known peace and prosperity, as early indicated, although there were also times when it had known what suffering was. While it had known plenty as in 1826 and in 1875 when the harvest was extremely good, or in 1917, when maguey commanded a good price, or even in our own days, when tobacco meant more substantial homes and better education for children (the PVTA Experimental Station was established in 1960, when Dr. Godofredo S. Reyes was Governor), Santa Maria also suffered hunger as in 1878 when the rain failed

to come and fields cracked up and practically no grains were harvested, or yet in 1896 when grasshoppers and other insects swooped down upon fields ready to harvest, or still in 1911 and 1913 when typhoons unleashed their fury turning what otherwise were productive fields into devastated areas which meant only hunger and privation and sufferings.

Measles and small pox took a heavy toll in 1908 and 1909, respectively, and in 1819 typhoid fever claimed

victims. In 1820, 1843, and 1902 cholera stalked the town, leaving each family mourning their dead, and depleting the town's population.

But if at times, dirges punctuated the deadly silence of the town, at others, martial music and excited

voices rent the air to welcome distinguished personages. who came to pay it a visit. Governor General Claveria visited the town in 1846, possibly the first Spanish governor general to visit it. Governor General Primo de Rivera also paid it a visit in 1879, and later - on November 12, 1898 - revisited it to mobilize

local volunteers to fight the Katipuneros who had earlier arrived, and had gone into hiding, in town on

august 15 of the same year. Records, however, are quite difficult for us to check these data, it might be well to take them as tentative.

Nevertheless, the town saw the fortunes and misfortunes of war, and witnessed the change of regimes, and politics take on a different color. It saw, for instance, the election of Julia Directo as first local president in September, 1898, during the first Philippine republic under Aguinaldo, at it also did the election of Sinforoso Tamayo as first municipal president under the Americans in 1901.

It also saw the visit of Governor General William Cameron Forbes who came to town in 1910 (later, during the commonwealth regime, Quezon would also drop by for a visit during a tour of the north).

Indeed, there was more freedom of movement during the American regime: not long after the last canon was

fired, survey teams were sent to various parts of the country. A report published in 1902, but which includes

observations made earlier has this to say of Santa Maria: "a pueblo on coast highway in Ilocos Sur, Luzon; several cart roads lead to interior; a beautiful city, well built and , by way, of a historical footnote,

adds that on "December 3, 1900. 2,150 Katipunan insurectos (sic) surrendered here , took oath of

allegiance to US."

Other early foreign travelers who had occasion to visit the town were favorably impressed by the church,

which they called a "cathedral".

A world traveller, Britisher A. Henry Savage Landor, visited Santa Maria in the course of his oriental tour, and has left us a rather typical picture of the town in the early 1900s. Says Langor: "... at Santa Maria a most picturesque church is to be found, reached by an imposing flight of steps. An enormous convent stands by the side of the church, upon a terrace some 80 feet above the plaza. There were a number of brick buildings, school-houses, and offices, which must have been very handsome, but are now tumbling down, the streets being in absolute possession of sheep, goats, and hogs. A great expanse of level land... was now well-cultivated into paddy-fields, and across it is a

beautiful road fifteen feet wide, well metalled and with a sandy surface. Barrios and houses were scattered all around the plain..

A LOOK AT THE FUTURE - The town will long remember the election in 1957 and 1959 of a fovorite son,

Dr. Godofredo S. Reyes, who became the first, and so far the only congressman and provincial governor of Ilocos Sur, from the town, although another son, Atty. Samuel F. Reyes had also been elected congressman, and later governor of Isabela, a fact which brought pride to Santa Marians. They, too, will remember the election of DRA. DedicacionM. Agatep-Reyes, as the first and so far the only, vice governor from the town in 1967.

All this warms the hearts of Santa Marians as they also remember others who have their imprint in their community's history, and of which they are justifiably proud. Such names come to mind as Arsenio F. Sebastian, who belonged to the very first batch of Philippine government pensionados sent for studies in the United States in 1903, and of his wife the former Isabel Florendo, who belonged to the second batch and was one of the very

first three women pensionados ever sent to the states and of Dr. Manuel Foronda, the first medical graduate

from the town who was also sent as pensionado tot he States in 1905. Again, one remembers with pride

Colonel Salvador F. Reyes, one of the country's earlliest graduates from West Point, and

Mrs. Helen Domingo Santos, one of the country's few women university presidents.

And the list can go on and on, for, as a tree is known by the fruit it bears, Santa Maria can, indeed, be proud of the other sons and daughters who have distinguished themselves and, therefore, have brought honor to their town: doctors like the Reyeses, the Florendos, the Julians, the Directos, the Domingos, and the Rillorazas;

lawyers like the Reyeses and Brillianteses, Florendos, and Camarillos, Domines, and Andrions; Journalists like

the de Duzmans and the Nolascos; creative writers like the Reyeses and the Forondas and the Guerzons; diplomats like the Guerzons; educators and teachers like the antonios, Moraleses, the Florendos, the Tamayos, and the

Agateps; scientists, engineers and statisticians like the Baldonados, the Mendozas, and the Reyeses; religious leaders like the Castros, the Moraleses, the Forondas and the Guerzons; military leaders like the Reyeses; men of business like the Pacquings and the Guererros; and men of politics like the late Mayor Joaquin Escobar and the present mayor, Dr. Ponciano S. Reyes.

Space limitations can only make this list far from complete, but it will continue to grow as the years go by, even as the era beginning the next one hundred years has unfolded.

for a town is not the church, nor the plaza, nor the municipal building, nor even the plains and the land

that sustains its very life; neither is it the industries nor great buildings of steel or concrete. A town is

a living, growing organism, and only its sons and daughters can make it grow even to greater heights.

The Santa Marian, at whatever time and in whatever place, knows that he has a tradition on which he can always look back with pride; he knows that he has honor and dignity to uphold; he is aware that has a mission to fulfill and that, he realizes, can only mean not only personal advance but even more important a social awareness to help his fellowman.

That realization can, indeed, make his celebration of the bicentennial of his own town even more relevant,

even as he now directs his eyes to the next hundred years.

[[Image:==Educational Institutions==

- Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College - formerly known as Ilocos Sur Agricultural College, it broke the norm that only one state college or university should exist per province. It is one of two State Colleges and Universities in the province (the other being the University of Northern Philippines).

The Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College was created by virtue of RA 8547 authored by Congressman Eric D. Singson

(2nd District, Ilocos Sur). It was signed into law by President Fidel V. Ramos on February 24, 1998. ISPSC is a

comprehensive multi-campus institution of higher learning with its main campus situated in Santa Maria, Ilocos Sur. The other campuses are strategically located in six municipalities in the second district of the province, with some in interior, upland municipalities. (Originally, ISPSC had eight (8) campuses, but the other two Salcedo Campus and Suyo Campus were reverted back to the Department of Education.)

The main campus was the former Ilocos Sur Agricultural College (ISAC) which had its early beginnings as a farm school way back in 1913. It evolved into an agricultural college in 1963 by virtue of RA 3529 authored by Cong.

Pablo C. Sanidad. In 1995, RA 7960 was passed into law which called for Cong. Eric D. Singson's vision for

establishing a multi-campus polytechnic college in the second district of Ilocos Sur. Presently, the main campus

is assigned as the College of Agriculture.

The six other campuses were then purely vocational-technical and general academic secondary schools when integrated

into the ISPSC.

The Tagudin General Comprehensive High School (TGCHS) is the oldest and the biggest in terms of student population.

It started in 1916 as a municipal high school and one of the oldest in the country. It became a national high

school in 1968 by virtue of RA 1477 courtesy of Cong. Pablo C. Sanidad. Tagudin campus is designated as the College of Arts and Sciences.

The Cervantes National Scho ol of Arts and Trades (CNSAT) started its operation in 1972. It was converted in 1983 into Cervantes National Agro-Industrial School (CNAIS) by virtue of RA 645_. Cervantes campus is one fo the three ISPSC campuses located in the upland, interior municipalities. The terrain is hilly and sloping appropriated for livestock production, orchard, and other agro-forest crops. Cervantes campus is the College of Agro-Industrial Technology.

The Southern Ilocos Sur School of Fisheries (SISSOF) metamorphosed from a fishery demonstration farm then known as the Ilocos Sur Marine Demonstration Farm (ISMDF) by virtue of PD 1050. It is located in the coastal barangay of Darapidap, Candon City, occupying an area of more than 11 hectares which was donated by the local government of Candon during the incumbency of then Mayor Eric D. Singson. With its integration into the polytechnic college it

became the College of Commercial and Social Services.

The Narvacan School of Fisheries (NASOF) was established in 1964 by virtue of RA 3476 authored by Cong. Pablo C. Sanidad. It is situated in the coastal barangay of Sulvec, Narvacan, Ilocos Sur and has an area of more than 10 hectares which was donated by three philanthropic families of the said barangay. It is now the College of Fisheries

and Marine Sciences.

The Ilocos Sur Experimental Station and Pilot School of Cattage Industries (ISESPCI) was established in 1974 by virtue of RA 4430. It is situated on a 3.5 hectare area along the national highway in the municipality of Santiago, Ilocos Sur. It had been offering post-secondary courses since 1989 before its integration. At present, Santiago campus is the College of Engineering and Technology. ]]

External links

17°21′31″N 120°29′53″E / 17.35861°N 120.49806°E