Cicero

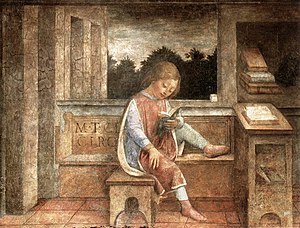

Marcus Tullius Cicero | |

|---|---|

Cicero around age 60 from an ancient marble bust | |

| Occupation | Politician, lawyer, orator and philosopher |

| Nationality | Ancient Roman |

| Subject | politics, law, philosophy, oratory |

| Literary movement | Golden Age Latin |

| Notable works | Politics: Pro Quinctio Philosophy: De Inventione |

Marcus Tullius Cicero (Classical Latin IPA: [ˈkikeroː], usually Template:PronEng in English; January 3, 106 BC – December 7, 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and philosopher. Cicero is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.[1][2]

Cicero is generally perceived to be one of the most versatile minds of ancient Rome. He introduced the Romans to the chief schools of Greek philosophy and created a Latin philosophical vocabulary, distinguishing himself as a linguist, translator, and philosopher. An impressive orator and successful lawyer, Cicero probably thought his political career his most important achievement. Today, he is appreciated primarily for his humanism and philosophical and political writings. His voluminous correspondence, much of it addressed to his friend Atticus, has been especially influential, introducing the art of refined letter writing to European culture. Cornelius Nepos, the 1st-century BC biographer of Atticus, remarked that Cicero's letters to Atticus contained such a wealth of detail "concerning the inclinations of leading men, the faults of the generals, and the revolutions in the government" that their reader had little need for a history of the period.[3]

During the chaotic latter half of the first century BC, marked by civil wars and the dictatorship of Gaius Julius Caesar, Cicero championed a return to the traditional republican government. However, his career as a statesman was marked by inconsistencies and a tendency to shift his position in response to changes in the political climate. His indecision may be attributed to his sensitive and impressionable personality; he was prone to overreaction in the face of political and private change. "Would that he had been able to endure prosperity with greater self-control and adversity with more fortitude!" wrote C. Asinius Pollio, a contemporary Roman statesman and historian.[4][5]

Early life

Childhood and family

Cicero was born January 3, 106 BC, in Arpinum (modern-day Arpino), a hill town 100 kilometres (70 miles) south of Rome. The Arpinians received Roman citizenship in 188 BC, but had started to speak Latin rather than their native Volscian before they were enfranchised by the Romans.[6] The assimilation of nearby Italian communities into Roman society, which took place during the Second and First Centuries, made Cicero's future as a Roman statesman, orator and writer possible. Although a great master of Latin rhetoric and composition, Cicero was not "Roman" in the traditional sense; he was quite self-conscious of this for his entire life.

During this period in Roman history, if one was to be considered "cultured", it was necessary to be able to speak both Latin and Greek. The Roman upper class often preferred Greek to Latin in private correspondence, recognizing its more refined and precise expressions, and its greater subtlety and nuance. Knowledge about Greek culture and literature was extremely influential for upper-class Roman society. When crossing the Rubicon in 49 B.C., one of the most symbolic and infamous events in Roman history, Caesar is said to have quoted the Athenian playwright Menander.[7] Greek was already being taught in Arpinum before the city was allied with Rome, which made assimilation into Roman society relatively seamless for the local elite.[8] Cicero, like most of his contemporaries, was also educated in the teachings of the ancient Greek rhetoricians, and most prominent teachers of oratory of the time were themselves Greek.[9] Cicero used his knowledge of Greek to translate many of the theoretical concepts of Greek philosophy into Latin, thus translating Greek philosophical works for a larger audience. He was so diligent in his studies of Greek culture and language as a youth that he was jokingly called the "little Greek boy" by his provincial family and friends. But it was precisely this obsession that tied him to the traditional Roman elite.[10]

Cicero's family belonged to the local gentry, domi nobiles, but had no familial ties with the Roman senatorial class. Cicero was only distantly related to one notable person born in Arpinium, Gaius Marius.[11] Marius led the populares faction during a civil war against the optimates of Lucius Cornelius Sulla in the 80s BC. Cicero received little political benefit from this connection. In fact, it may have hindered his political aims, as the Marian faction was ultimately defeated and anyone connected to the Marian regime was viewed as a potential troublemaker.[12]

Cicero's father was a well-to-do equestrian (knight) with good connections in Rome. Though he was a semi-invalid who could not enter public life, he compensated for this by studying extensively. Although little is known about Cicero's mother, Helvia, it was common for the wives of important Roman citizens to be responsible for the management of the household. Cicero's brother Quintus wrote in a letter that she was a thrifty housewife.[13]

Cicero's cognomen, personal surname, is Latin for chickpea. Romans often chose down-to-earth personal surnames. Plutarch explains that the name was originally given to one of Cicero's ancestors who had a cleft in the tip of his nose resembling a chickpea. Plutarch adds that Cicero was urged to change this deprecatory name when he entered politics, but refused, saying that he would make Cicero more glorious than Scaurus ("Swollen-ankled") and Catulus ("Puppy").[14]

Studies

According to Plutarch, Cicero was an extremely talented student, whose learning attracted attention from all over Rome,[15] affording him the opportunity to study Roman law under Quintus Mucius Scaevola.[16] In the same way, years later, a young Marcus Caelius Rufus and other young lawyers would study under Cicero; an association of the sort was considered a great honour to both teacher and pupil. He also had the support of his family's patrons, Marcus Aemilius Scaurus and Lucius Licinius Crassus. The latter was a model to Cicero both as an orator and as a statesman.

Cicero's fellow students with Scaevola were Gaius Marius Minor, Servius Sulpicius Rufus (who became a famous lawyer, one of the few whom Cicero considered superior to himself in legal matters), and Titus Pomponius. The latter two became Cicero's friends for life, and Pomponius (who received the cognomen "Atticus" for his philhellenism) would become Cicero's chief emotional support and adviser. "You are a second brother to me, an 'alter ego' to whom I can tell everything," Cicero wrote in one of his letters to Atticus.[17]

In his youth, Cicero tried his hand at poetry, although his main interests lay elsewhere. His poetic works include translations of Homer and the Phaenomena of Aratus, which later influenced Virgil to use that poem in the Georgics.

In the late 90's and early 80's BC Cicero fell in love with philosophy, which was to have a great role in his life. He would eventually introduce Greek philosophy to the Romans and create a philosophical vocabulary for it in Latin. The first philosopher he met was the Epicurean philosopher Phaedrus, when he was visiting Rome ca. 91 BC. His fellow student at Scaevola's, Titus Pomponius, accompanied him. Titus Pomponius (Atticus), unlike Cicero, would remain an Epicurean for the rest of his life.

In 87 BC, Philo of Larissa, the head of the Academy that was founded by Plato in Athens about 300 years earlier, arrived in Rome. Cicero, "inspired by an extraordinary zeal for philosophy",[18] sat enthusiastically at his feet and absorbed Plato's philosophy, even calling Plato his god. He most admired Plato's moral and political seriousness, but he also respected his breadth of imagination. Cicero nonetheless rejected Plato's theory of Ideas.

Shortly thereafter, Cicero met Diodotus, an exponent of Stoicism. Stoicism had already been introduced to Roman society during the previous generation, and it maintained popular appeal among the Romans. Cicero did not completely accept stoicism's austere philosophy, but he did adopt a modified stoicism prevalent during the time. Diodotus the Stoic became Cicero's protégé and lived in his house until his death. Diodotus demonstrated a truly Stoic attitude when he continued to study and teach despite losing his sight.[18]

Public service

Early career

Cicero's childhood dream was "Always to be best and far to excel the others," a line taken from Homer's Iliad.[19] Cicero pursued dignitas (position) and auctoritas (authority), symbolized by the purple-bordered toga praetexta and the Roman lictors' rod. There was just one path to these: public civil service along the steps of Cursus honorum. However, in 90 BC he was too young to apply to any of the offices of Cursus honorum except to acquire the preliminary experience in warfare that a career in civil service demanded. In 90 BC–88 BC, Cicero served both Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo and Lucius Cornelius Sulla as they campaigned in the Social War, though he had no taste for military life. Cicero was first and foremost an intellectual. Several years later he would write to his friend, Titus Pomponius Atticus who was collecting marble statues for Cicero's villas: "Why do you send me a statue of Mars? You know I am a pacifist!"[20]

Cicero started his career as a lawyer around 83-81 BC. His first major case of which a written record is still extant was his 80 BC defense of Sextus Roscius on the charge of parricide.[21] Taking this case was a courageous move for Cicero; parricide and matricide were considered appalling crimes, and the people whom Cicero accused of the murder — the most notorious being Chrysogonus — were favorites of Sulla. At this time it would have been easy for Sulla to have Cicero murdered, as Cicero was barely known in the Roman courts.

His arguments were divided into three parts: in the first, he defended Roscius and attempted to prove he did not commit the murder; in the second, he attacked those who likely committed the crime — one being a relative of Roscius — and stated how the crime benefitted them more than Roscius; in the third, he attacked Chrysogonus, stating Roscius' father was murdered to obtain his estate at a cheap price. On the strength of this case, Roscius was acquitted.

Cicero's successful defense was an indirect challenge to the dictator Sulla. In 79 BC, Cicero left for Greece, Asia Minor and Rhodes, perhaps due to the potential wrath of Sulla. Accompanying him were his brother Quintus, his cousin Lucius, and probably Servius Sulpicius Rufus.[22]

Cicero travelled to Athens, where he again met Atticus, who had fled war-torn Italy to Athens in the 80s. Atticus had become an honorary citizen of Athens and introduced Cicero to some significant Athenians. In Athens, Cicero visited the sacred sites of the philosophers. The most important of them was the Academy of Plato, where he conversed with the present head of the Academy, Antiochus. Because Cicero's philosophical stance was very similar to that of the New Academy as represented by Philo of Larissa, he felt that Antiochus had moved too far away from his predecessor.[23] He was also initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries, which made a strong impression on him, and consulted the oracle at Delphi. But first and foremost he consulted different rhetoricians in order to learn a less exhausting style of speaking. His chief instructor was the rhetorician Apollonius Molon of Rhodes. He instructed Cicero in a more expansive and less intense (and less strenuous on the throat) form of oratory that would define Cicero's individual style in years to come.

Entry into politics

After his return to Rome, Cicero's reputation rose very quickly, assisting his elevation to office as a quaestor in 75 BC (the next step on the cursus honorum). Quaestors, 20 of whom were elected annually, dealt with the financial administration at Rome or assisted in financial matters as propraetor or proconsul (both governors) in one of the provinces of Rome. Cicero served as quaestor in western Sicily in 75 BC and demonstrated honesty and integrity in his dealings with the inhabitants. As a result, the grateful Sicilians became his clients, and he was asked by them to prosecute Gaius Verres, a governor of Sicily, who had badly plundered Sicily.

During his stay in Sicily he discovered, hidden by thick bushes and undergrowth, the tomb of Archimedes of Syracuse, on whose gravestone was carved Archimedes' favourite discovery in geometry: that the ratio of the volume of a sphere to that of the smallest right circular cylinder in which it fits is 2:3.[24][25]

The prosecution of Gaius Verres in 70 BC was a great forensic success for Cicero. Verres' defense counsel was Rome's greatest lawyer and orator in those days, Quintus Hortensius. Verres was convicted, and he fled into exile. Upon the conclusion of this case, Cicero came to be considered the greatest orator in Rome, surpassing Hortensius. Relations between Hortensius and Cicero remained friendly despite this rivalry.

Oratory was considered a great art in ancient Rome and an important tool for disseminating knowledge and promoting oneself in elections. Oratory was important because there was only one "newspaper" in Rome, created in 130 BC, Acta Diurna (Daily Resolutions), which was published by the Senate and of limited circulation.

Despite his great success as an advocate, Cicero lacked reputable ancestry: he was neither noble nor patrician. A further hindrance was that the last memorable "new man" to have been elected consulate without consular ancestors had been the politically radical and militarily innovative Gaius Marius — a distant relative of Cicero's who also came from Arpinum.

Cicero grew up in a time of civil unrest and war. Sulla’s victory in the first of many civil wars led to a new constitutional framework that undermined libertas (liberty), the fundamental value of the Roman Republic. Nonetheless, Sulla’s reforms strengthened the position of the equestrian class, contributing to that class’s growing political power. Cicero was both an Italian eques and a novus homo, but more importantly he was a constitutionalist, meaning he did not wish to side with the populares faction and embark on a campaign of "seditious" reform. His social class and loyalty to the Republic ensured he would "command the support and confidence of the people as well as the Italian middle classes." This appeal was undercut by his lack of social standing and a reliable and viable power base, as the equites, his primary base of support, did not hold much power. The optimates faction never truly accepted Cicero, despite his outstanding talents and vision for the security of the Republic. This undermined his efforts to reform the Republic while preserving the constitution. Nevertheless, he was able to successfully ascend the Roman cursus honorum, holding each magistracy at or near the youngest possible age: quaestor in 75 (age 31), curule aedile in 69 (age 37), praetor in 66 (age 40), and finally consul at age 43.

Consul

Cicero was elected Consul for the year 63 BC, defeating patrician candidate Lucius Sergius Catiline. During his year in office he thwarted a conspiracy to overthrow the Roman Republic, led by Catiline. Cicero procured a Senatus Consultum de Re Publica Defendenda (a declaration of martial law, also called the Senatus Consultum Ultimum), and he drove Catiline from the city with four vehement speeches which came to be known as the Catiline Orations. The Orations listed Catiline and his followers' debaucheries, and denounced Catiline's senatorial sympathizers as roguish and dissolute debtors, clinging to Catiline as a final and desperate hope. Cicero demanded Catiline and his followers to leave the city. At the conclusion of his first speech, Catiline burst from the Temple of Jupiter Stator, where the Senate had convened, and made his way to Etruria. In his following speeches Cicero did not directly address Catiline but instead addressed the Senate. By these speeches Cicero wanted to prepare the Senate for the worst possible case; he also delivered more evidence against Catiline.

Catiline fled and left behind his followers to start the revolution from within while Catiline assaulted the city with an army recruited from among Sulla’s veterans in Etruria. Many peasant farmers who were racked by debt also supported Catiline in the countryside. These five parties had attempted to involve the Allobroges, a tribe of Transalpine Gaul, in their plot, but Cicero, working with the Gauls, was able to seize letters which incriminated the five conspirators and forced them to confess their crimes in front of the Senate.[26]

The Senate then deliberated upon the conspirators' punishment. As it was the dominant advisory body to the various legislative assemblies rather than a judicial body, there were limits to its power; however, martial law was in effect, and it was feared that simple house arrest or exile — the standard options — would not remove the threat to the state. At first most in the Senate spoke for the "extreme penalty"; many were then swayed by Julius Caesar, who decried the precedent it would set and argued in favor of life imprisonment in various Italian towns. Cato then rose in defence of the death penalty and all the Senate finally agreed on the matter. Cicero had the conspirators taken to the Tullianum, the notorious Roman prison, where they were strangled. Cicero himself accompanied the former consul Publius Cornelius Lentulus Sura, one of the conspirators, to the Tullianum. After the executions had been carried out, Cicero announced the deaths by the formulaic expression Vixerunt ("they have lived," which was meant to ward off ill fortune by avoiding the direct mention of death).

Cicero received the honorific "Pater Patriae" for his efforts to suppress the conspiracy, but lived thereafter in fear of trial or exile for having put Roman citizens to death without trial. He also received the first public thanksgiving for a civic accomplishment; previously this had been a purely military honor. Cicero's four Catiline Orations remain outstanding examples of his rhetorical style.

Civil war

Exile and return

In 61 BC Julius Caesar invited Cicero to be the fourth member of his existing partnership with Pompey and Marcus Licinius Crassus, an assembly that would eventually be called the First Triumvirate. Cicero refused the invitation because he suspected it would undermine the Republic.[27]

In 58 BC Publius Clodius Pulcher, the tribune of the plebs, introduced a law threatening exile to anyone who executed a Roman citizen without a trial. Cicero, having executed members of the Catiline conspiracy four years before without formal trial, and having had a public falling-out with Clodius, was clearly the intended target of the law. Cicero argued that the senatus consultum ultimum indemnified him from punishment, and he attempted to gain the support of the senators and consuls, especially of Pompey. When help was not forthcoming, he went into exile. He arrived at Thessalonica, Greece on May 23, 58 BC.[28] The day Cicero left Italy, Clodius proposed another bill which forbade Cicero approaching within 400 miles of Italy and confiscated his property. The bill was passed forthwith, and Cicero's villa on the Palatine was destroyed by Clodius' supporters, as were his villas in Tusculum and Formiae.[29][30]

Cicero's exile caused him to fall into depression. He wrote to Atticus: "Your pleas have prevented me from committing suicide. But what is there to live for? Don't blame me for complaining. My afflictions surpass any you ever heard of earlier". In another letter to Atticus, Cicero suggested that the Senate was jealous of him, and this was why they declined to recall him from exile. In a later letter to his brother Quintus, he named several factors he believed contributed to his exile: "the defection of Pompey, the hostility of the senators and judges, the timidity of equestrians, the armed bands of Clodius." Atticus borrowed 25,000 sestertii for Cicero's cause and, with Cicero's wife Terentia, attempted to recall him from exile.[31]

Cicero returned from exile on August 5, 57 BC, and landed in Brundisium (modern Brindisi).[32] He was greeted by a cheering crowd, and, to his delight, his beloved daughter Tullia. Elated, he returned to Rome, where some time later the Senate passed a resolution restoring his property and ordered reparations to be paid for damages done to him.[33]

During the 50s BC Cicero supported Milo, who at the time was Clodius' chief opponent. Clodius typically drew his political support from armed mobs and political violence, and he was slain by Milo’s gladiators on the Via Appia in 52 BC.[34] Clodius' relatives brought charges of murder against Milo, who appealed to Cicero for advocacy. Cicero took the case, and his speech Pro Milone came to be considered by some as his crowning masterpiece.

In Pro Milone, Cicero argued that Milo had no reason to kill Clodius - indeed, Cicero proposed, Milo had everything to gain from Clodius being alive. Furthermore, he asserted that Milo did not expect to encounter Clodius on the Via Appia. The prosecution pointed out that the few living witnesses to the murder were Milo's slaves, and that by subsequently freeing them, Milo had cynically ensured no witness would testify against him. Though Cicero suggested that the slaves' valiant defence of Milo was cause enough for their emancipation, he ultimately lost the case. After the trial, Milo went into exile and continued to live in Massilia until he returned to stir up trouble in the Civil War.

The struggle between Pompey and Julius Caesar grew more intense in 50 BC. Cicero, rather forced to pick sides, chose to favour Pompey, but at the same time he prudently avoided openly alienating Caesar. When Caesar invaded Italy in 49 BC, Cicero fled Rome. Caesar, seeking the legitimacy that endorsement by a senior senator would provide, courted Cicero's favour, but even so Cicero slipped out of Italy and in June traveled to Dyrrachium (Epidamnos), Illyria, where Pompey's staff was situated.[35] Cicero traveled with the Pompeian forces to Pharsalus in 48 BC, though he was quickly losing faith in the competence and righteousness of the Pompeian lot. He quarrelled with many of the commanders, including a son of Pompey himself. Eventually, he even provoked the hostility of his fellow senator Cato, who told him that he would have been of more use to the cause of the optimates if he had stayed in Rome. In Cicero's own words: "I came to regret my action in joining the army of the optimates not so much for the risk of my own safety as for the appalling situation which confronted me on arrival. To begin with, our forces were too small and had poor morale. Secondly, with the exception of the commander-in-chief and a handful of others, everyone was greedy to profit from the war itself and their conversation was so bloodthirsty that I shuddered at the prospect of victory. In a word everything was wrong except the cause we were fighting for."[36] After Caesar's victory at Pharsalus, Cicero returned to Rome only very cautiously. Caesar pardoned him and Cicero tried to adjust to the situation and maintain his political work, hoping that Caesar might revive the Republic and its institutions.

In a letter to Varro on c. April 20 46 BC, Cicero outlined his strategy under Caesar's dictatorship: "I advise you to do what I am advising myself – avoid being seen even if we cannot avoid being talked about. If our voices are no longer heard in the Senate and in the Forum, let us follow the example of the ancient sages and serve our country through our writings concentrating on questions of ethics and constitutional law".[37]

Opposition to Mark Antony, and death

Cicero was taken completely by surprise when the Liberatores assassinated Caesar on the ides of March, 44 BC. Cicero was not included in the conspiracy, even though the conspirators were sure of his sympathy. Marcus Junius Brutus called out Cicero's name, asking him to "restore the Republic" when he lifted the bloodstained dagger after the assassination.[38] A letter Cicero wrote in February 43 BC to Trebonius, one of the conspirators, began, "How I could wish that you had invited me to that most glorious banquet on the Ides of March"![39] Cicero became a popular leader during the period of instability following the assassination. He had no respect for Mark Antony, who was scheming to take revenge upon Caesar's murderers. In exchange for amnesty for the assassins, he arranged for the Senate to agree not to outlaw Caesar as a tyrant, which allowed the Caesarians to have lawful support.

Cicero and Antony then became the two leading men in Rome; Cicero as spokesman for the Senate and Antony as consul, leader of the Caesarian faction, and unofficial executor of Caesar's public will. The two men had never been on friendly terms and their relationship worsened after Cicero made it clear that he felt Antony to be taking unfair liberties in interpreting Caesar's wishes and intentions. When Octavian, Caesar's heir and adopted son, arrived in Italy in April, Cicero formed a plan to play him against Antony. In September he began attacking Antony in a series of speeches he called the Philippics, in honour of his inspiration – Demosthenes. Praising Octavian to the skies, he labelled him a "god-sent child" and said that the young man only desired honour and would not make the same mistake as his adoptive father. Meanwhile, his attacks on Antony, whom he called a "sheep", rallied the Senate in firm opposition to Antony. During this time, Cicero's popularity as a public figure was unrivalled and according to the historian Appian, he "had the [most] power any popular leader could possibly have".[40] Cicero heavily fined the supporters of Antony for petty charges and had volunteers forge arms for the supporters of the Republic. According to Appian, although the story is not supported by others, this policy was perceived by Antony's supporters to be so insulting that they prepared to march on Rome to arrest Cicero. Cicero fled the city and the plan was abandoned.

Cicero supported Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus as governor of Cisalpine Gaul (Gallia Cisalpina) and urged the Senate to name Antony an enemy of the state. One tribune, a certain Salvius, delayed these proceedings and was "reviled", as Appian put it, by Cicero and his party. The speech of Lucius Piso, Caesar's father-in-law, delayed proceedings against Antony. Antony was later declared an enemy of the state when he refused to lift the siege of Mutina, which was in the hands of Decimus Brutus. Cicero described his position in a letter to Cassius, one of Caesar's assassins, that same September: "I am pleased that you like my motion in the Senate and the speech accompanying it. Antony is a madman; corrupt and much worse than Caesar whom you declared the worst of evil men when you killed him. Antony wants to start a bloodbath".[41]

Cicero’s plan to drive out Antony failed, however. After the successive battles of Forum Gallorum and Mutina, Antony and Octavian reconciled and allied with Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate. Immediately after legislating their alliance into official existence for a five-year term with consular imperium, the Triumvirate began proscribing their enemies and potential rivals. Cicero and his younger brother Quintus Tullius Cicero, formerly one of Caesar's legati, and all of their contacts and supporters were numbered among the enemies of the state[citation needed] though, reportedly, Octavian argued for two days against Cicero being added to the list.[42]

Among the proscribed, Cicero was one of the most viciously and doggedly hunted. Other victims included the tribune Salvius, who, after siding with Antony, moved his support directly and fully to Cicero. Cicero was viewed with sympathy by a large segment of the public and many people refused to report that they had seen him. He was eventually caught leaving his villa in Formiae in a litter going to the seaside from where he hoped to embark on a ship to Macedonia.[43] When the assassins arrived his own slaves said they had not seen him, but he was given away by Philologus, a freed slave of his brother Quintus Cicero.[43]

Cicero's last words were said to have been "there is nothing proper about what you are doing, soldier, but do try to kill me properly". He was decapitated by his pursuers on December 7, 43 BC at Formia. His head and hands were displayed on the Rostra in the Forum Romanum according to the tradition of Marius and Sulla, both of whom had displayed the heads of their enemies in the Forum. He was the only victim of the Triumvirate's proscriptions to be so displayed. According to Cassius Dio[44] (in a story often mistakenly attributed to Plutarch), Antony's wife Fulvia took Cicero's head, pulled out his tongue, and jabbed it repeatedly with her hairpin in final revenge against Cicero's power of speech.[45]

Cicero's son, Marcus Tullius Cicero Minor, during his year as a consul in 30 BC, avenged his father's death somewhat when he announced to the Senate Mark Antony's naval defeat at Actium in 31 BC by Octavian and his capable commander-in-chief Agrippa. In the same meeting the Senate voted to prohibit all future Antonius descendants from using the name Marcus.

Later on, Octavian came upon one of his grandsons reading a book by Cicero. The boy tried to conceal it, fearing his grandfather's reaction. Octavian (now called Augustus) took the book from him, read a part of it, and then handed the volume back, saying: "He was a learned man, dear child, a learned man who loved his country".[46]

Personal life

Marriages

Cicero married Terentia probably at the age of 27, in 79 BC. The marriage, which was a marriage of convenience, was harmonious for some 30 years. Terentia was of patrician background and a wealthy heiress, both important concerns for the ambitious young man that Cicero was at this time. One of her sisters, or a cousin, had been chosen to become a Vestal Virgin – a very great honour. Terentia was a strong-willed woman and (citing Plutarch) "she took more interest in her husband's political career than she allowed him to take in household affairs".[47] She did not share Cicero's intellectual interests nor his agnosticism. Cicero laments to Terentia in a letter written during his exile in Greece that "neither the gods whom you have worshipped with such a devotion nor the men that I have ever served, have shown the slightest sign of gratitude toward us".[48] She was a pious and probably a rather down-to-earth person.

In the 40s Cicero's letters to Terentia became shorter and colder. He complained to his friends that Terentia had betrayed him but did not specify in which sense. Perhaps the marriage simply could not outlast the strain of the political upheaval in Rome, Cicero's involvement in it, and various other disputes between the two. The divorce appears to have taken place in 45. The divorce enabled Terentia to protect her finances, as it would have made her a woman sui iuris,[49] and thus would also have kept more money in Terentia's accounts for later inheritance by their two children, Tullia Ciceronis and Marcus Tullius Cicero Minor.

In late 46 BC Cicero married a young girl, Publilia, who had been his ward. It is thought that Cicero needed her money, particularly after having to repay the dowry of Terentia, who came from a wealthy family.[50] This marriage did not last long. Shortly after the marriage had taken place Cicero's daughter, Tullia, died. Publilia had been jealous of her and was so unsympathetic over her death that Cicero divorced her. Several friends of his, among them Caerellia, a woman who shared Cicero's interest in philosophy, tried to mend the break but he remained adamant.[51]

Tullia and Marcus

It is commonly known that Cicero held great love for his daughter Tullia, although his marriage to Terentia was one of convenience. He describes her in a letter to his brother Quintus: "How affectionate, how modest, how clever! The express image of my face, my speech, my very soul."[52] When she suddenly became ill in February 45 BC and died after having seemingly recovered from giving birth to a son in January, Cicero was stunned. "I have lost the one thing that bound me to life" he wrote to Atticus.[51]

Atticus told him to come for a visit during the first weeks of his bereavement, so that he could comfort him when his pain was at its greatest. In Atticus' large library, Cicero read everything that the Greek philosophers had written about overcoming grief, "but my sorrow defeats all consolation."[53] Caesar and Brutus sent him letters of condolence. So did his old friend and colleague, the lawyer Servius Sulpicius Rufus. He sent an exquisite letter that posterity has much admired, full of subtle, melancholy reflection on the transiency of all things.[54][55]

After a while, he withdrew from all company to complete solitude in his newly acquired villa in Astura. It was in a lonely spot, but not far from Neapolis (modern Naples). For several months he just walked in the woods, crying. "I plunge into the dense wild wood early in the day and stay there until evening", he wrote to Atticus.[56] Later he decided to write a book for himself on overcoming grief. This book, Consolatio, was highly appreciated in antiquity (and made an immense impression on St. Augustine), but is unfortunately lost.[57] A few fragments have survived, among them the poignant: "I have always fought against Fortune, and beaten her. Even in exile I played the man. But now I yield, and throw up my hand."[58] He also planned to erect a small temple to the memory of Tullia, "his incomparable daughter." But he dropped this plan after a year, for reasons unknown.[59]

Cicero hoped that his son Marcus would become a philosopher like him, but that was wishful thinking. Marcus himself wished for a military career. He joined the army of Pompey in 49 BC and after Pompey's defeat at Pharsalus 48 BC, he was pardoned by Caesar. Cicero sent him to Athens to study as a disciple of the peripatetic philosopher Kratippos in 48 BC, but he used this absence from "his father's vigilant eye" to "eat, drink and be merry."[60]

After his father's murder he joined the army of the Liberatores but was later pardoned by Augustus. Augustus' bad conscience for having put Cicero on the proscription list during the Second Triumvirate led him to aid considerably Marcus Minor's career. He became an augur, and was nominated consul in 30 BC together with Augustus, and later appointed proconsul of Syria and the province of Asia.[61]

Political and social thought

Cicero’s vision for the Republic was not simply the maintenance of the status quo. Nor was it a straightforward desire to revitalise what many, such as Sallust, term the ‘moral degradation’ of the republican system. Cicero envisioned a Rome ruled by a selfless nobility of successful individuals determining the fate of the nation via consensus in the Senate. Cicero’s country and equestrian background resulted in a broader outlook, not marred by self-interest to the same extent as the patricians of Rome.

Cicero aspired to a republican system dominated by a ruling aristocratic class of men, “who so conducted themselves as to win for their policy the approval of all good men.” Further, he sought a concordia ordinum, an alliance between the senators and the equites. This ‘harmony between the social classes,’ which he later developed into a consensus omnium bonorum to include tota Italia (all citizens of Italy), demonstrated Cicero’s foresight as a statesman. He understood that fundamental change to the organization and the distribution of power within the Republic was required to secure its future. Cicero believed ‘the best men’ would institute large-scale reforms which were contrary to their interests as the ruling oligarchy. Cicero believed that only "some sort of free state" would engender stability and justice.[62]

Links with the equestrian class, combined with his status as a novus homo meant that Cicero was isolated from the optimates. Thus, it is not surprising that Cicero envisioned a "selfless nobility of successful individuals" rather than the patrician-dominated system. The fact remains that those who sat in the Senate had appropriated huge profits by exploiting the provinces. Repeatedly, the oligarchy had proved to be short-sighted, reactionary and "operating with restricted and outmoded institutions that could no longer cope with the vast territories containing multifarious populations that was Rome at this point of its history." The repeated failings of the oligarchy were not only due to the leading patricians like Crassus and Hortensius, but also to the influx of conservative equites into the Senate’s ranks.

The combination of the Roman governing system, presently used by the oligarchy to selfishly maximize economic exploitation, and the introduction of the business minded equites, only resulted in an increase of the plundering of resources within the Empire. The large-scale extortion destabilized the political system further, which was continuously under pressure by both foreign wars and from the populares. Moreover, this period of Roman history was marked by constant in-fighting between the senators and the equites over political power and control of the courts. The problem arose because Sulla originally enfranchised the equites, but then these privileges were soon removed after he stepped down from office. Cicero, as an eques, naturally backed their claims to participate in the legal process; moreover, the constant conflict was incompatible with his vision of a concordia ordinum. The conflict between the two classes showed no signs of short-term resolution. The ruling class for over a century had showed nothing of ‘selfless service’ to the Republic and through their actions only undermined its stability, contributing to the creation of a society ripe for revolution.

The establishment of individual power bases both within Rome and in the provinces undermined Cicero’s guiding principle of a free state, and thus the Roman Republic itself. This factionalised the Senate into cliques, which constantly engaged each other for political advantage. These cliques were the optimates, led by such figures as Cato, and in later years Pompey, and the populares, led by such men as Julius Caesar and Crassus. It is important to note that although the optimates were generally republicans there were instances of leaders of the optimates with distinctly dictatorial ways. Caesar, Crassus and Pompey were at one time the head of the First Triumvirate, which directly conflicted with the republican model as it did not comply with the system of holding a consulship for one year only. Cicero’s vision for the Republic could not succeed if the populares maintained their position of power. Cicero did not envisage widespread reform, but a return to the "golden age" of the Republic. Despite Cicero’s attempts to court Pompey over to the republican side, he failed to secure either Pompey’s genuine support or peace for Rome.

After the civil war, Cicero recognised that the end of the Republic was almost certain. He stated that "the Republic, the Senate, the law courts are mere ciphers and that not one of us has any constitutional position at all." The civil war had destroyed the Republic. It wreaked destruction and decimated resources throughout the Roman Empire. Julius Caesar’s victory had been absolute. Caesar’s assassination failed to reinstate the Republic, despite further attacks on the Romans’ freedom by "Caesar’s own henchman, Mark Antony." His death only highlighted the stability of ‘one man rule’ by the ensuing chaos and further civil wars that broke out with Caesar’s murderers, Brutus and Cassius, and finally between his own supporters, Mark Antony and Octavian.

Cicero remained the "Republic's last true friend" as he spoke out for his ideals and of the libertas (freedom) the Romans enjoyed for centuries. Cicero’s vision had some fundamental flaws. It harked back to a ‘golden age’ that may never have existed. Cicero's idea of the concordia ordinum was too idealistic. Also, Roman institutions had failed to keep pace with Rome's enormous expansion. The Republic had reached such a state of disrepair that regardless of Cicero’s talents and passion, Rome lacked "persons loyal to [the Republic] to trust with armies." Cicero lacked the political power, nor had he any military skill or resources, to command true power to enforce his ideal. To enforce republican values and institutions was ipso facto contrary to republican values. He also failed to a certain extent to recognize the real power structures that operated in Rome.[citation needed]

Works

Cicero was declared a “righteous pagan” by the early Catholic Church, and therefore many of his works were deemed worthy of preservation. Saint Augustine and others quoted liberally from his works “On The Republic” and “On The Laws,” and it is due to this that we are able to recreate much of the work from the surviving fragments. Cicero also articulated an early, abstract conceptualisation of rights, based on ancient law and custom.

Books

Of Cicero's books, six on rhetoric have survived, as well as parts of eight on philosophy.

Speeches

Of his speeches, eighty-eight were recorded, but only fifty-eight survive. Some of the items below are more than one speech.

- Judicial speeches

- (81 BC) Pro Quinctio (On behalf of Publius Quinctius)

- (80 BC) Pro Sex. Roscio Ameriae (On behalf of Sextus Roscius of Ameria)

- (77 BC) Pro Q. Roscio Comoedo (On behalf of Quintus Roscius Gallus the Actor)

- (70 BC) Divinatio in Caecilium (Spoken against Caecilius at the inquiry concerning the prosecution of Gaius Verres)

- (70 BC) In Verrem (Against Gaius Verres, or The Verrines)

- (71 BC) Pro Tullio (On behalf of Tullius)

- (69 BC) Pro Fonteio (On behalf of Marcus Fonteius)

- (69 BC) Pro Caecina (On behalf of Aulus Caecina)

- (66 BC) Pro Cluentio (On behalf of Aulus Cluentius)

- (63 BC) Pro Rabirio Perduellionis Reo (On behalf of Gaius Rabirius on a Charge of Treason)

- (63 BC) Pro Murena (On behalf of Lucius Licinius Murena)

- (62 BC) Pro Sulla (On behalf of Publius Cornelius Sulla)

- (62 BC) Pro Archia Poeta (On behalf of the poet Aulus Licinius Archias)

- (59 BC) Pro Flacco (On behalf of Lucius Valerius Flaccus)

- (56 BC) Pro Sestio (On behalf of Sestius)

- (56 BC) In Vatinium (Against Publius Vatinius at the trial of Sestius)

- (56 BC) Pro Caelio (On behalf of Marcus Caelius Rufus): English translation

- (56 BC) Pro Balbo (On behalf of Cornelius Balbus)

- (54 BC) Pro Plancio (On behalf of Plancius)

- (54 BC) Pro Rabirio Postumo (On behalf of Gaius Rabirius Postumus)

Several of Cicero's speeches are printed, in English translation, in the Penguin Classics edition Murder Trials. These speeches are included:

- In defence of Sextus Roscius of Ameria (This is the basis for Steven Saylor's novel Roman Blood.)

- In defence of Aulus Cluentius Habitus

- In defence of Gaius Rabirius"

- Note on the speeches in defence of Caelius and Milo

- In defence of King Deiotarus

- Political speeches

- Early career (before exile)

- (66 BC) Pro Lege Manilia or De Imperio Cn. Pompei (in favor of the Manilian Law on the command of Pompey)

- (63 BC) De Lege Agraria contra Rullum (Opposing the Agrarian Law proposed by Rullus)

- (63 BC) In Catilinam I-IV (Catiline Orations or Against Catiline) Error in Webarchive template: Empty url.

- (59 BC) Pro Flacco (In Defense of Flaccus)

- Mid career (after exile)

- (57 BC) Post Reditum in Quirites (To the Citizens after his recall from exile)

- (57 BC) Post Reditum in Senatu (To the Senate after his recall from exile)

- (57 BC) De Domo Sua (On his House)

- (57 BC) De Haruspicum Responsis (On the Responses of the Haruspices)

- (56 BC) De Provinciis Consularibus (On the Consular Provinces)

- (55 BC) In Pisonem (Against Piso)

- Late career

- (52 BC) Pro Milone (On behalf of Titus Annius Milo)

- (46 BC) Pro Marcello (On behalf of Marcellus)

- (46 BC) Pro Ligario (On behalf of Ligarius before Caesar)

- (46 BC) Pro Rege Deiotaro (On behalf of King Deiotarus before Caesar)

- (44 BC) Philippicae (consisting of the 14 philippics, Philippica I–XIV, against Marcus Antonius)[1]

(The Pro Marcello, Pro Ligario, and Pro Rege Deiotaro are collectively known as "The Caesarian speeches").

Philosophy

- Rhetoric

- (84 BC) De Inventione (About the composition of arguments)

- (55 BC) De Oratore (About oratory)

- (54 BC) De Partitionibus Oratoriae (About the subdivisions of oratory)

- (52 BC) De Optimo Genere Oratorum (About the Best Kind of Orators)

- (46 BC) Paradoxa Stoicorum (Stoic Paradoxes)

- (46 BC) Brutus (For Brutus, a short history of Roman oratory dedicated to Marcus Junius Brutus)

- (46 BC) Orator ad M. Brutum (About the Orator, also dedicated to Brutus)

- (45 BC) De Fato (On Fate)

- (44 BC) Topica (Topics of argumentation)

- (?? BC) Rhetorica ad Herennium (traditionally attributed to Cicero, but currently disputed)

- Other philosophical works

- (51 BC) De Re Publica (On the Republic)

- (45 BC) Hortensius (Hortensius)

- (45 BC) Lucullus or Academica Priora (The Prior Academics)

- (45 BC) Academica Posteriora (The Later Academics)

- (45 BC) Consolatio (Consolation) How to console oneself at the death of a loved person

- (45 BC) De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum (About the Ends of Goods and Evils) - a book on ethics.[2] Source of Lorem ipsum

- (45 BC) Tusculanae Quaestiones (Questions debated at Tusculum)

- (45 BC) De Natura Deorum (On the Nature of the Gods)

- (45 BC) De Divinatione (On Divination)

- (44 BC) Cato Maior de Senectute (Cato the Elder On Old Age)

- (44 BC) Laelius de Amicitia (Laelius On Friendship)

- (44 BC) De Officiis (On duties)

- (?? BC) De Legibus (On the Laws)

- (?? BC) De Consulatu Suo (On his ((Cicero's)) consulship - epic poem, only parts survive)

- (?? BC) De temporibus suis (His Life and Times- epic poem, only parts survive)

- (?? BC) Commentariolum Petitionis (Handbook of Candidacy)[3] (attributed to Cicero, but probably written by his brother Quintus)

Letters

More than 800 letters by Cicero to others exist, and over 100 letters from others to him.

- (68 BC-43 BC) Epistulae ad Atticum (Letters to Atticus)

- (59 BC-54 BC) Epistulae ad Quintum Fratrem (Letters to his brother Quintus)

- (43 BC) Epistulae ad Brutum (Letters to Brutus)

- (43 BC) Epistulae ad Familiares (Letters to his friends)

In popular culture

Appearances in modern fiction, listed in order of publication

- Julius Caesar, by William Shakespeare

- Titus Andronicus, by William Shakespeare

- Ides of March, (1948) an epistolary novel by Thornton Wilder

- A Pillar of Iron, a (1965) fictionalized biography, by Taylor Caldwell

- Masters of Rome series, by Colleen McCullough; Cicero first appears as a precocious young boy in The Grass Crown

- Roma Sub Rosa series, (1991-2005), by Steven Saylor

- Robert Olen Butler imagines Cicero's last thoughts as a short monologue in Severance (2006)

- Imperium, a (2006) novel, by Robert Harris; Imperium is the first of a trilogy on the life of Cicero, with the second book Conspiracy to be published in late 2008.

Appearances in film and television

- Imperium: Augustus, a British-Italian film (2003), also shown as Augustus The First Emperor in some countries, where Cicero (played by Gottfried John) appears in several vignettes.

- In the 2005 ABC miniseries Empire, Cicero (played by Michael Byrne) appears as a supporter of Octavius. This portrayal deviates sharply from history, as Cicero survives the civil war to witness Octavius assume the title of princeps.

- The HBO/BBC2 TV series Rome features Marcus Tullius Cicero prominently and is played by David Bamber. The portrayal broadly adheres to the historical record, reflecting Cicero's political indecision and continued switching of allegiances between the various factions in Rome's civil war. A disparity occurs in his assassination, which occurs in an orchard rather than on the road to the sea. The TV series also depicts Cicero's assassination at the hands of the fictionalized Titus Pullo, though the historical Titus Pullo was not Cicero's actual killer.

See also

- Titus Pomponius Atticus

- Caecilia Attica

- Quintus Tullius Cicero

- Marcus Tullius Tiro

- Tullia Ciceronis

- Lorem Ipsum

- Category:Works by Cicero

Further reading

- Francis A. Yates (1974). The Art of Memory, University of Chicago Press, 448 pages, Reprint: ISBN 0-226-95001-8

- Taylor Caldwell (1965), A Pillar of Iron, Doubleday & Company, Reprint: ISBN 0-385-05303-7

Notes

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero, a portrait (1975) p.303

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero (1964)p.300-301

- ^ Cornelius Nepos, Atticus 16, trans. John Selby Watson.

- ^ Haskell, H.J.:"This was Cicero" (1964) p.296

- ^ Castren and Pietilä-Castren: "Antiikin käsikirja" /"Handbook of antiquity" (2000) p.237

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero, a portrait (1975) p.1

- ^ Plutarch: "Lives" p.874

- ^ Rawson, E.:"Cicero, a portrait" (1975) p.7.

- ^ Rawson, E.:"Cicero, a portrait" (1975) p.8

- ^ Everitt, A.:"Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome's Greatest Politician" (2001) p.35

- ^ Rawson, E. "Cicero, a portrait" (1975) p.2-3

- ^ Rawson, E.:"Cicero, a portrait"(1975) p.17

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero, a portrait (1975) p.5-6; Cicero, Ad Familiares 16.26.2 (Quintus to Cicero)

- ^ Plutarch, Cicero 1.3–5

- ^ Plutarch, Cicero 2.2

- ^ Plutarch, Cicero 3.2

- ^ Rawson, Elizabeth: "Cicero, a portrait" (1975) p. 14-15

- ^ a b Rawson:"Cicero, a portrait" (1975) p.18

- ^ Everitt, A.: "Cicero, a turbulent life" (2001) p.43

- ^ Cicero: Samtliga brev (Collected letters) in Swedish translation by G.Sjögren 1963

- ^ Rawson, E.: "Cicero, a portrait" (1975) p.22

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: "This was Cicero" (1940) p.83

- ^ Rawson, E.:"Cicero, a portrait" (1975) p.27.

- ^ Haskell, J.J.: This was Cicero (1964) p.108.

- ^ Cicero, Tusculan Disputations, Book V, Sections 64-66 excerpt

- ^ Cicero, In Catilinam 3.2; Sallust, Bellum Catilinae 40-45; Plutarch, Cicero 18.4

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero, 1984 106

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero, 1964 200

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero, 1964 p.201

- ^ Plutarch. Cicero 32

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero, 1964, p.201-202. See also Garcea, A.: Cicerone in esilio. L’epistolario e le passioni, Hildesheim: Olms. 2005

- ^ Cicero, Samtliga brev/Collected letters (in a Swedish translation)

- ^ Haskell. H.J.: This was Cicero, p.204

- ^ Rawson, Elizabeth: "Cicero, A portrait" (1975)p.329

- ^ Everitt, Anthony: Cicero pp. 215.

- ^ Everitt, Anthony: Cicero: A turbulent life. p.208

- ^ Cicero, Ad Familiares 9.2

- ^ Cicero, Second Philippic Against Antony

- ^ Cicero, Ad Familiares 10.28

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 4.19

- ^ Cicero, Ad Familiares 12.2

- ^ Plutarch, Cicero 46.3–5

- ^ a b Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero (1964) p.293

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History 47.8.4

- ^ Everitt, A.: Cicero, A turbulent life (2001)

- ^ Plutarch, Cicero, 49.5

- ^ Rawson, E.: "Cicero, a portrait" (1975) p.25

- ^ Haskell, H.J.:"This was Cicero"(1964)p.96

- ^ Ulpian, Digest 50.16.195.

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero p.225

- ^ a b Haskell, H.J.:"This was Cicero" (1964) p.249

- ^ Haskell H.J.: This was Cicero, p.95

- ^ Cicero, Letters to Atticus, 12.14. Rawson, E.: Cicero p. 225

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero p.226

- ^ Cicero, Samtliga brev/Collected letters

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero, p.250

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero, p.225-227

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero p.251

- ^ Rawson, E.: Cicero, p.250

- ^ Haskell, H.J.: This was Cicero (1964) p.103- 104

- ^ Paavo Castren & L. Pietilä-Castren: Antiikin käsikirja/Encyclopedia of the Ancient World

- ^ James Leigh Strachan-Davidson. Rome. 1894, p. 427

References

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius, Cicero’s letters to Atticus, Vol, I, II, IV, VI, Cambridge University Press, Great Britain, 1965

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius, Latin extracts of Cicero on Himself, translated by Charles Gordon Cooper , University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1963

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius, Selected Political Speeches, Penguin Books Ltd, Great Britain, 1969

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius, Selected Works, Penguin Books Ltd, Great Britain, 1971

- Everitt, Anthony 2001, Cicero: the life and times of Rome's greatest politician, Random House, hardback, 359 pages, ISBN 0-375-50746-9

- Cowell, Cicero and the Roman Republic, Penguin Books Ltd, Great Britain, 1973

- Haskell, H.J.: (1946) This was Cicero, Fawcett publications, Inc. Greenwich, Conn. USA

- Gibbon, Edward. (1793). The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire., The Modern Library (2003), ISBN 0375758119. Edited, Abridged, and with a Critical Foreword by Hans-Friedrich Mueller.

- Gruen, Erich, The last Generation of the Roman Republic, University of California Press, USA, 1974

- March, Duane A., "Cicero and the 'Gang of Five'," Classical World, volume 82 (1989) 225-234

- Plutarch, Fall of the Roman Republic, Penguin Books Ltd, Great Britain, 1972

- Rawson, Elizabeth (1975) Cicero, A portrait, Allen Lane, London ISBN 0-7139-0864-5

- Rawson, Elizabeth, Cicero, Penguin Books Ltd, Great Britain, 1975

- Scullard, H. H. From the Gracchi to Nero, University Paperbacks, Great Britain, 1968

- Smith, R. E., Cicero the Statesman, Cambridge University Press, Great Britain, 1966

- Strachan-Davidson, J. L., Cicero and the Fall of the Roman Republic, University of Oxford Press, London, 1936

- Taylor, H. (1918). Cicero: A sketch of his life and works. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co.

External links

- General:

- [4] LATINUM - Anglice et Latine - Extensive Latin language learning podcast. Listen to Cicero Read Aloud.

- Works by Cicero:

- Online Library of Liberty

- Works by Cicero at Project Gutenberg

- Perseus Project (Latin and English): Classics Collection (see: M. Tullius Cicero)

- The Latin Library (Latin): Works of Cicero

- UAH (Latin, with translation notes): Cicero Page

- De Officiis, translated by Walter Miller

- Cicero's works: text, concordances and frequency list

- Biographies and descriptions of Cicero's time:

- At Project Gutenberg

- Plutarch's biography of Cicero contained in the Parallel Lives

- Life of Cicero by Anthony Trollope, Volume I – Volume II

- Cicero by Rev. W. Lucas Collins (Ancient Classics for English Readers)

- Roman life in the days of Cicero by Rev. Alfred J. Church

- Social life at Rome in the Age of Cicero by W. Warde Fowler

- At Heraklia website

- Dryden's translation of Cicero from Plutarch's Parallel Lives

- At Middlebury College website

- At Project Gutenberg

- SORGLL: Cicero, In Catilinam I; I,1-3, read by Robert Sonkowsky

- 106 BC births

- 43 BC deaths

- Ancient Roman rhetoricians

- Ancient Roman executions

- Ancient Roman senators

- Classical humanists

- Golden Age Latin authors

- Humor theorists

- Latin writers

- Latin letter writers

- People from the Province of Frosinone

- Political theorists

- Roman era philosophers

- Roman Republican consuls

- Ancient Roman jurists

- Tullii

- Executed writers

- Roman Republic