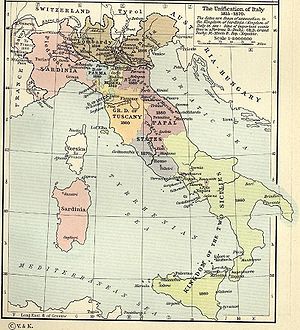

Italian irredentism

Territories around Italy claimed as Irredent by nationalistic organizations (In clockwise order from north):

Istria-Venezia Giulia (now in Slovenia and Croatia)

Dalmatia (Croatia and Montenegro)

Ionian islands (Greece)

Malta (Malta)

Corsica (France)

Nizzardo (France)

Savoia (France)

Ticino (Switzerland)

Italia Irredenta (Meaning "Unredeemed Italy" in Italian) was an Italian nationalist movement that aimed to complete the unification of all Italian peoples. Originally, the movement promoted the annexation to Italy of territories inhabited by an Italian majority but retained by the Austrian Empire after 1866 (hence "unredeemed" Italy). These included the Trentino, Trieste, Istria, Fiume, and parts of Dalmatia.

The liberation of Italia irredenta was perhaps the strongest motive for Italy's entry into World War I and the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 satisfied many irredentist claims.[1]

Not a formal organization, it was just an opinion movement that claimed that Italy had to reach its "natural borders". Similar patriotic and nationalistic ideas were common in Europe in the 19th century. The term "irredentism" was successively imitated - from the italian word - for many countries in the world (List of irredentist claims or disputes). This idea of "Italia irredenta" is not to be confused with the Risorgimento, which was the historical events that led to irredentism, or with Greater Italy, which was the political philosophy that took the idea further under Fascism.

Origins

After the Italian unification of 1861, there were areas with Italian populations in the countries around the newly created Kingdom of Italy. The Irredentists wanted to annex all those areas under one Italy and decided that anywhere using the Italian language (no matter if the speakers weren't necessarily all Italians) would be included in the proposed merging.

These targeted areas initially were: Corsica, Dalmatia, Gorizia and Gradisca, Ionian islands, Istria, Malta, Nice, Ticino, Trentino, Trieste and Fiume.

19th century

One of the first "Irredentists" was Giuseppe Garibaldi, who in 1859, as deputy for his native Nizza in the Piedmontese parliament at Turin, attacked Cavour for ceding Nice to Napoleon III (in order to get French help and approval for the Italian Unification). The Irredentism grew in importance in Italy in the next years.

On July 21, 1878, a noisy public meeting was held at Rome with Menotti Garibaldi (the son of unification leader Giuseppe Garibaldi) as chairman of the forum, and a clamour was raised for the formation of volunteer battalions to conquer the Trentino. Benedetto Cairoli, then Prime Minister of Italy, treated the agitation with tolerance.

It was, however, mainly superficial, because the mass of the Italians had no wish to launch on a dangerous policy of adventure against Austria, and still less to attack France for the sake of Nice and Corsica, or Britain for Malta.

One consequence of the Irredentist ideas outside of Italy was the assassination plot organized against the Emperor Francis Joseph in Trieste in 1882, which was detected. Guglielmo Oberdan (a Triestine and thus Austrian citizen) was executed. When the Irredentist movement became troublesome to Italy through the activity of Republicans and Socialists, it was subject to effective police control by Agostino Depretis.

Irredentism faced a setback when the French occupation of Tunis in 1881 started a crisis in French–Italian relations. The government entered into relations with Austria and Germany, which took shape with the formation of the Triple Alliance in 1882.

20th century

The process of unification to Italy of the targeted areas was not completed in the nineteenth century, as many Italians remained outside the borders of the Kingdom of Italy and the government started to create colonies (Eritrea and Somalia) in Africa.

World War 1

The Habsburg Monarchy permanently made obstacles to the Italian interests on Eastern Adriatic, by supporting the Slav community in its territory at the expense of Italian population of Istria and Dalmatia. Part of that policy was the supporting of pro-Croatian and pro-Slovenian parties, keeping and promoting their language as official in the targeted provinces. This policy resulted in a huge emigration of Italians from Istria and Dalmatia and the rise of nationalistic movements of revenge in Italy that promoted war against the Austrians.

Italian irredentism obtained an important result after World War I, when Italy gained Trieste, Gorizia, Istria and the cities of Rijeka and Zadar. Fascist irredentism added to Italy (temporarily during WWII) Corsica, Nizzardo and most of Dalmatia (including the Kotor), while occupied militarily Savoia and the Ionian islands.

Italy signed the London Pact and entered World War I with the intention of gaining those territories perceived as being Italian under foreign rule; several Austro-Hungarian citizens of Italian ethnicity fought within the Italian forces against Austria-Hungary to "free their lands". Some, such as Cesare Battisti, Nazario Sauro, Damiano Chiesa, Fabio Filzi, were captured and executed. The outcome of the First World War and the consequent settlement of the Treaty of Saint-Germain ensured Italy some of its claims, in accordance with the Treaty of London of 1915, including many (but not all) of the aims of the Italia irredenta party, incorporating Trento, Bolzano, Trieste and Istria. [2]

In Dalmatia, despite the treaty of London, only the city of Zara with some Dalmatian islands, like Cherso, Lussino and Curzola were assigned to Italy.

The city of Fiume/Rijeka in bay of Kvarner was the subject of claim and counter-claim (see Italian Regency of Carnaro, Treaty of Rapallo, 1920 and Treaty of Rome, 1924).

The stand taken by Gabriele D'Annunzio, which briefly led him to become an enemy of the Italian state [3], was meant to provoke a nationalist revival through Corporatism (first instituted during his rule over Fiume), in front of what was widely perceived as state corruption engineered by governments such as Giovanni Giolitti's. D'Annunzio briefly annexed to this "Regency of Carnaro" the Dalmatian islands of Veglia (Krk) and Arbe (Rab) where there was a numerous Italian community.

Fascism and World War 2

Fascist Italy strove to be seen as the natural result of war heroism, against a "betrayed Italy" that had not been awarded all it deserved, as well as appropriating the image of Arditi soldiers. In this vein, irredentist claims were expanded and often used in Fascist Italy's desire to control the Mediterranean basin.

In 1922 Mussolini temporarily occupied Corfu, perhaps using irredentist claims based on minorities of Italians in the Ionian islands of Greece {fact}. Similar tactics may have been used towards the islands around the Kingdom of Italy - through the Maltese Italians, Corfiot Italians and Corsican Italians - in order to control the Mediterranean sea (that he called (in Latin) Mare Nostrum)[citation needed].

Around 1939, the main territories sought included the rest of Istria, more of Dalmatia, the Ionian Islands (in Greece), Malta, Corsica, Nice, Savoy and Ticino. Other claims were also made by for the "Fourth Shore", which meant coastal Libya and Tunisia, and The Dodecanese islands of the Aegean Sea.

During World War II, large parts of Dalmatia were annexed to Italy, in the Governatorato di Dalmazia from 1941 to 1943. Corsica and Nice were also administratively annexed to the Kingdom of Italy in November 1942. Malta was heavily bombed but was not occupied, because a planned invasion by Italo-German forces was delayed in 1942 and never done.[citation needed]

After Italy's capitulation in 1943, areas formerly under Italian control in Istria and Venezia Giulia were conquered for short period by Tito's partisans, and the first repression of Italians occurred. Shortly afterwards these areas were occupied by the German Wehrmacht, that bloodily suppressed the partisans' rule, especially on Istrian peninsula.

After 1945, about 350,000 persons opted to leave to Italy[2]. The "disappearance" of the Italian speaking populations in Istria and Dalmatia was nearly complete after World War II.[4].

Italian irredentism today

After WWII Italian Irredentism faded away together with the defeated Fascism and the Monarchy of the Savoia. But some Italian organizations -mainly related to the istrian exodus - still do propaganda for Irredentism, with the approval of far right political parties. One of the main reasons behind this contemporary Irredentism is the economic one, related to the restitution of properties confiscated by the Yugoslav government to the 350,000 Italians exiled from Istria and Dalmatia after 1945.

Some Croatian and Slovenian nationalistic organizations and institutions complain that Italy - in their opinions - openly propagates irredentistic ideas even in the 21st century, which often causes sharp reactions of Croatian and Slovenian officials.

Here it is a list of the most relevant episodes in recent years:

- Vicepresident of Italian government, Gianfranco Fini, told to Croatian journalists on 51. gathering of the association of the Italians who went away from Yugoslavia after WWII, in Senigallia, that "...from the son of an Italian from Rijeka...I've first time learned that those areas were and are Italian, but not just because of that that in certain historical moment our armies have planted Italians there. That country was Venetian, and before that Roman" [3]. Instead of issuing an official denial of those words, Carlo Giovanardi, minister for the relations with Parliament in Berlusconi's government, coldly confirmed Fini's words, saying "...that he told the truth".[4].

- On 52. gathering of the same association, Carlo Giovanardi also told in 2005, that "Italy'll execute cultural, economical and touristic invasion in order to 'reconstruct the Italianhood of Dalmatia' ", while participating on round table, together with neofascist and irredentist persons, discussing about the topic "Italy and Dalmatia today and tomorrow" (note: organizers intentionally evade the noun "Croatia" in title) [5]. Giovanardi later declared that he had been misunderstood [6].

- Roberto Menia, a deputy of Alleanza Nazionale in Italian Parliament, has been regularly verbally attacking institutions of Italians from Croatia (especially Italian Union) and its leaders and honorable persons (publicist and writer Giacomo Scotti was favourite target of those attacks), calling them as titoists, traitors and slavocommunists, although those persons and institutions were keeping the culture of Croatian Italians alive. Menia also supported the etiquette, told by Italian consul in Rijeka, Roberto Pietrosanto, in which Pietrosanto called those institutions as fifthcolumnist.[7]

- Alleanza Nazionale has often claimed that Italy paid too much for her defeat in WWII, repeating that "Dalmatia was stolen to Italy"[citation needed].

- In 2005, Menia has told, that "when Croatia joins EU, Italy will return to Istria, Fiume [he used the Italian name of Rijeka ] and Dalmatia". [5]

- In 2001, Italian president Carlo Azeglio Ciampi gave the golden medal (for the aerial bombings endured during WWII) to the last Italian administration of Zara (today Zadar, Croatia), represented by its Gonfalone, which is currently owned by the association "Free municipality of Zara in exile". Croatian authorities complained that he was awarding a fascist institution, although the motivations for the golden medal explicitly recalled the contribution of the city to the Resistance against Fascism. The motivations were contested by several Italian right wing associations, such as the same "Free municipality of Zara in exile" and the Lega Nazionale[8].

- In February 2007 (on "Foibe Memorial Day"), Italian President Giorgio Napolitano gave a statement in which he used phrases like "one of the barbarhoods of the century", "movement of hate and bloodthirsty rage", "Slavic annectionist project", when speaking about the Foibe massacres[9]. The European Commission did not comment on this event, but did comment (and partly condemn) the response by Croatian president Stjepan Mesić, when he said that "it's impossible not to see in Napolitano's statements traces of open racism, historical revisionism and political revanchism", asking for toning down and warned the Croatian President "not to use too sharp phrases". [10]

- On December 12, 2007, the Italian post office issued a stamp with a photo of the Croatian city of Rijeka and with the text "Rijeka - eastern land once part of Italy" ("Fiume-terra orientale già italiana") [11] [12]. The same sources declared that the severeness of this act could seen in use of prepositions and adjectives - adfirming that "già italiana" could also mean "already Italian". But according to Italian syntaxis the correct meaning in this case is only "previously Italian". The stamp was printed in 3.5 million of copies. [5] [6], but was not delivered to the public by the Italian Post Office in order to forestall a possible diplomatic crisis with Croatian and Slovenian authorities.[13] [7]

- Napolitano's statement in Feb 2008 (on "Foibe Memorial Day"), in which he reconfirmed his statements from 2007, and called Mesić's reactions from 2007 as "unjustified", caused sharp reaction from the Office of the Croatian President Stipe Mesić on 11 Feb 2008, in which it was said, that as a reaction to this Napolitano's statement, there's no need to change any word from Mesić's last year's reaction.[10][14]

Some Italian exiles believe that all these complaints made by Croatian authorities (like President Mesic) are due to the fact that there it is a growing movement in Italy (and Europe) toward asking for the official recognition of "genocide" [8] of the Italians in Istria and Dalmatia (like has been done with the Armenian massacre done by the Turks). [15] They argue that there it is a long history of ethnic cleansing in Croatia, as reported by many historians.[16]

Dalmatia: a case of Italian Irredentism

The linguist Matteo Bartoli calculated that the Italians were nearly 30% of the Dalmatian population at the beginning of the Napoleonic wars[17], while currently there are only 300 Italians in Croatian Dalmatia and 500 Italians in coastal Montenegro. Bartoli's evaluation was followed with other claims such as 25% in 1814/1815 (according to a census done by the french Auguste De Marmont, governor-general of the napoleonic Illyrian provinces) and, 3 years later, around 70,000 of Italians in a total of 301,000 people living in Austrian Dalmatia.

Yugoslavian scholars (like Večerina, Duško) complained that all these evaluations were not conducted by modern scientific standards and concentrated solely on the spoken language of the population. They pinpointed that according to report of the court councillor Joseph Fölch in 1827, Italian language was in usage not only by noblemen, but also by some citizens of lower classes only in the coastal cities Zara, Sebenico and Spalato. Since only around 20.000 people populated these cities and they were not all Italian speakers, their real number for those Yugoslavian scholars was rather much smaller probably around 5% [18].

Italian irredentists (like Gabriele D'Annunzio) argued to the above Yugoslavian critics that Joseph Fölch forgot the Dalmatian islands of Cherso/Chres, Lussino/Lusinj, Lissa/Vis, etc. with huge Italian communities and that the only official evidences about the Dalmatian population come from the Austrian census: the 1857 Austro-Hungarian census (here) precisely showed that in this year there were in Dalmatia 369.310 Slavs and 45.000 Italians. That means that the Dalmatian Italians were officially 15% of the total population of Dalmatia in mid XIX century[19].

The last bastion of Italian presence in Dalmatia was the city of Zara. In the Habsburg empire census of 1910 the city of Zara had an Italian population of 9,318 (or 69,3% out of the total of 13,438 inhabitants). Zara population grew to 24,100 inhabitants, of which 20,300 Italians, when was in 1942 the capital of the Governatorate of Dalmatia (the "Governatorate" fulfilled the aspirations of the Italian Irredentism in the Adriatic).

Then came the surrender of Italy in September 1943 and for the Italians of Zara started a terrible period of time, that made their city to be called the Italian Dresden.

In 1943 Tito, pretending the town was an important supply centre for the German divisions in Yugoslavia, persuaded the Allies of its military importance. The Anglo-Americans, between 2 November 1943 and 31 October 1944, razed it to the ground with fifty-four bombardments. As a consequence, at least 2,000 people were buried beneath the rubble, about 10-12,000 people took refuge in Trieste and slightly over one thousand reached Apulia. Tito’s partisans entered in Zara on 31 October 1944, and 138 people were shot, killed or drowned [20].

With the Peace Treaty of 1947, the Italians still living in Zara - no more than three thousands - were granted by Tito the opportunity to choose to become Italian citizens but with the obligation to take up residence in Italy. Actually, after WWII and the Italian exodus from Dalmatia there are only 100 Dalmatian Italians in this city.

Political figures in the Italian Irredentism

- Guglielmo Oberdan

- Cesare Battisti

- Nazario Sauro

- Damiano Chiesa

- Fabio Filzi

- Carmelo Borg Pisani

- Giuseppe Garibaldi

- Gabriele D'Annunzio

- Petru Simone Cristofini

- Petru Giovacchini

- Maria Pasquinelli

See also

- Irredentism

- Italians

- Italian Regency of Carnaro

- Italian Unification

- History of Italy as a monarchy and in the World Wars

- Italian Empire

References

- ^ http://www.bartleby.com/65/ir/irredent.html Columbia Encyclopedia

- ^ Summary of Ermanno Mattioli's book and Summary of historian Enrico Miletto's book

- ^ Slobodna Dalmacija Gianfranco Fini: "Dalmacija, Rijeka i Istra oduvijek su talijanske zemlje", Oct 13, 2004 ("Dalmatia, Rijeka and Istria have forever been Italian lands")

- ^ Slobodna Dalmacija Utroba koja je porodila talijanski iredentizam još uvijek je plodna, Mar 18, 2006 (The bowels that gave birth to Italian irrendentism are still fertile)

- ^ a b Template:Hr icon Nacional Talijanski ministar najavio invaziju na Dalmaciju, Oct 19, 2005

(Italian minister announced an invasion on Dalmatia) - ^ Corriere dela Sera Veleni nazionalisti sulla casa degli italiani, Oct 21, 2005 (Nationalist poisons on the house of Italians)

- ^ Slobodna Dalmacija Menia želi kontrolu nad 8 milijuna eura za Talijansku uniju, Feb 2, 2005

(Menia wants control over 8 mil. euros for Italian Union) - ^ Lega Nazionale Medaglia d'oro al comune di Zara (Golden Medal to the Municipality of Zara)

- ^ Template:It iconCorriere della Sera Napolitano: "Foibe, ignorate per cecità" Feb 2, 2007 (Napolitano: "Foibe, ignored for blindness")

- ^ a b Net.hr Mesić iznenađen govorom Napolitana

- ^ Template:Hr icon Index.hr MVP uputio prosvjednu notu Italiji zbog poštanske marke s nacionalističkim natpisom

(The Croatian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has sent a protest note to Italy, because of issue of a stamp with nationalistic text) - ^ B92 - Internet, Radio and TV station Zagreb protests over Italian stamp

- ^ Stoppato il francobollo per Fiume, bufera

- ^ http://www.javno.com/en/croatia/clanak.php?id=122615 Croatian President Surprised By Napolitano Speech

- ^ http://www.adnkronos.com/AKI/English/Politics/?id=1.0.1865663799 Italy-Croatia: World War II killings were ethnic cleansing, Napolitano says

- ^ http://www.ess.uwe.ac.uk/comexpert/ANX/IV.htm The policy of ethnic cleansing (1994)/Final report of the United Nations Commission of Experts established pursuant to Security Council resolution 780 (1992), about massacres done by Croats (and others) in former Iugoslavia in the early nineties

- ^ Bartoli, Matteo. Le parlate italiane della Venezia Giulia e della Dalmazia. p.46

- ^ [1] O broju Talijana/Talijanaša u Dalmaciji XIX. Stoljeća”, , Zavod za povijesne znanosti HAZU u Zadru, 2002, UDK 949.75:329.7”19”Dalmacija 2002, p. 344

(“Concerning the number of Italians/pro-Italians in Dalmatia in the XIXth century”) - ^ Statistisches Handbüchlein für die österreichische Monarchie, edited by the k.k. Direktion der administrativen Statistik

- ^ Lovrovici, don Giovanni Eleuterio. Zara dai bombardamenti all'esodo (1943-1947) Tipografia Santa Lucia - Marino. Roma, 1974. pag.66

Bibliography

- Bartoli, Matteo. Le parlate italiane della Venezia Giulia e della Dalmazia. Tipografia italo-orientale. Grottaferrata, 1919.

- Colonel von Haymerle, Italicae res, Vienna, 1879 - the early history of Irredentists.

- Lovrovici, don Giovanni Eleuterio. Zara dai bombardamenti all'esodo (1943-1947). Tipografia Santa Lucia - Marino. Roma, 1974.

- Petacco, Arrigo. A tragedy revealed: the story of Italians from Istria, Dalmatia, Venezia Giulia (1943-1953). University of Toronto Press. Toronto, 1998

- Večerina, Duško. Talijanski Iredentizam ( Italian Irredentism ), ISBN 953-98456-0-2, Zagreb, 2001

- Vivante, Angelo. Irredentismo adriatico (The Adriatic Irredentism), 1984

External links

- Articles on the History of Dalmatia

- Articles on the Italians in Dalmatia

- Articles on Zara (Zadar), when was a city of the Kingdom of Italy.

- Slovene - Italian relations between 1880-1918

- Irredentists

- Website of the Italian irredentism (in Italian)

- Hrvati AMAC Gdje su granice (EU-)talijanskog bezobrazluka? (Where are the limits of Italian arrogancy?; page contains the speech of Italian deputy) (in Croatian)

- Hrvati AMAC 'Božićni darovi' poniženoj Hrvatskoj (Christmas gifts to humiliated Croatia; page contains the scan of the incriminated stamp) (in Croatian)

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Slobodna Dalmacija Počasni građanin Zadra kočnica talijanskoj ratifikaciji SSP-a (in Croatian)

- D'Annunzio and Fiume (in Italian)

- Politicamentecorretto.com Onorevole Guglielmo Picchi Forza Italia (in Italian)

- Italia chiama Italia Francobollo Fiume: bloccata l'emissione (in Italian)

- Trieste.rvnet.eu Stoppato” il francobollo per Fiume, bufera: protestano Unione degli istriani, An e Forza Italia (contains the scan of the stamp) (in Italian)