Coccyx

| Coccyx | |

|---|---|

The coccyx is formed of up to five vertebrae. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os coccygis |

| MeSH | D003050 |

| TA98 | A02.2.06.001 |

| TA2 | 1092 |

| FMA | 20229 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The coccyx (pronounced kok-siks), commonly referred to as the tailbone, is the final segment of the human vertebral column. Comprising three to five separate or fused vertebrae (the coccygeal vertebrae) below the sacrum, it is attached to the sacrum by a fibrocartilaginous joint, the sacrococcygeal symphysis, which permits limited movement between the sacrum and the coccyx.

The term coccyx comes originally from the Greek language and means "cuckoo", referring to the shape of a cuckoo's beak.[1]

Function

In humans and other tailless primates (e.g. great apes) since Nacholapithecus (a Miocene hominoid)[2], the coccyx is the remnant of a vestigial tail, but still not entirely useless;[3] it is an important attachment for various muscles, tendons and ligaments — which makes it important for physicians and patients to remember the importance of these attachments when considering surgical removal of the coccyx.[1] Additionally, it is also part of the weight-bearing tripod structure which act as a support for a sitting person. When a person sits leaning forward, the ischial tuberosities and inferior rami of the ischium take most of the weight, but as the sitting person leans backward, more weight is transferred to the coccyx.[1]

The anterior side of the coccyx serve for the attachment a group of muscles important for many functions of the pelvic floor (i.e. defecation, continence, etc): The levator ani muscle, which include coccygeus, iliococcygeus, and pubococcygeus. Through the anococcygeal raphé, the coccyx supports the position of the anus. Attached to the posterior side is gluteus maximus which extend the thigh during ambulation.[1]

Many important ligaments attach to the coccyx: The anterior and posterior sacrococcygeal ligaments are the continuations of the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments that stretches along the entire spine.[1] Additionally, the lateral sacrococcygeal ligaments complete the foramina for the last sacral nerve.[4] And, lastely, some fibers of the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments (arising from the spine of the ischium and the ischial tuberosity respectively) also attach to the coccyx.[1]

Structure

The coccyx is usually formed of four rudimentary vertebrae (sometimes five or three). It articulates superiorly with the sacrum. In each of the first three segments may be traced a rudimentary body and articular and transverse processes; the last piece (sometimes the third) is a mere nodule of bone. All the segments are destitute of pedicles, laminae and spinous processes. The first is the largest; it resembles the lowest sacral vertebra, and often exists as a separate piece; the last three diminish in size from above downward.

Most anatomy books wrongly state that the coccyx is normally fused in adults. In fact it has been shown[5][6] that the coccyx may consist of up to five separate bony segments, the most common configuration being two or three segments. Only about 5 percent[failed verification] of the population have a coccyx in one piece, separate from the sacrum, as described in anatomy books.

Surfaces

The anterior surface is slightly concave and marked with three transverse grooves that indicate the junctions of the different segments. It gives attachment to the anterior sacrococcygeal ligament and the Levatores ani and supports part of the rectum.

The posterior surface is convex, marked by transverse grooves similar to those on the anterior surface, and presents on either side a linear row of tubercles, the rudimentary articular processes of the coccygeal vertebrae. Of these, the superior pair are large, and are called the coccygeal cornua; they project upward, and articulate with the cornua of the sacrum, and on either side complete the foramen for the transmission of the posterior division of the fifth sacral nerve.

Borders

The lateral borders are thin and exhibit a series of small eminences, which represent the transverse processes of the coccygeal vertebrae. Of these, the first is the largest; it is flattened from before backward, and often ascends to join the lower part of the thin lateral edge of the sacrum, thus completing the foramen for the transmission of the anterior division of the fifth sacral nerve; the others diminish in size from above downward, and are often wanting. The borders of the coccyx are narrow, and give attachment on either side to the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments, to the coccygeus in front of the ligaments, and to the gluteus maximus behind them.

Apex

The apex is rounded, and has attached to it the tendon of the Sphincter ani externus. It may be bifid.

Sacrococcygeal and intercoccygeal joints

The joints are variable and may be: (1) synovial joints; (2) thin discs of fibrocartilage; (3) intermediate between these two; (4) ossified.[7][8]

Pathology

Injuring the coccyx can give rise to a condition called coccydynia.[9] [10] A number of tumors are known to involve the coccyx; of these, the most common is sacrococcygeal teratoma. Both coccydynia and coccygeal tumors may require surgical removal of the coccyx (coccygectomy). One complication of cocygectomy is a coccygeal hernia.[11]

Additional images

-

Vertebral column.

-

Vertebral column.

-

Left Levator ani from within.

-

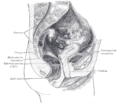

Median sagittal section of male pelvis.

-

Median sagittal section of female pelvis.

See also

- Coccydynia (coccyx pain, tailbone pain)

- Bone terminology

- Terms for anatomical location

- Ganglion impar

- Human vestigial

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Foye (2008), eMedicine

- ^ Masato (2004), Acquisition of bipedalism

- ^ Saladin (2003), p 268

- ^ Morris (2005), p 59

- ^ Postachini (1983), pp 1116-1124

- ^ Kim & Suk (1999), pp 215-20

- ^ Maigne et al (1992), pp 34–35

- ^ Saluja (1988), pp 11–15

- ^ Maigne (2000), pp 3072-3079

- ^ Foye (2006), pp 783–4

- ^ Miranda et al (2007)

References

- Foye P, Buttaci C, Stitik T, Yonclas P (2006). "Successful injection for coccyx pain". Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 85 (9). doi:10.1097/01.phm.0000233174.86070.63. PMID 16924191.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Foye, Patrick M (June 3, 2008). "Coccyx Pain". eMedicine.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Kim NH; Suk KS] (1999 Jun). "Clinical and radiological differences between traumatic and idiopathic coccygodynia". Yonsei Medical Journal (40:3).

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - Maigne JY, Molinie V, Fautrel B. (1992). "Anatomie des disques coccygiens". Revue de Médecine Orthopedique. 28.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Maigne, J-Y (2000). "Causes and Mechanisms of Common Coccydynia. Spine". 25 (23). coccyx.org.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Nakatsukasa, Masato (2004 May). "Acquisition of bipedalism: the Miocene hominoid record and modern analogues for bipedal protohominids". Journal of Anatomy (204(5)): 385–402. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8782.2004.00290.x.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) (See Fig. 5 entitled First coccygeal/caudal vertebra in short-tailed or tailless primates..) - Miranda EP, Anderson AL, Dosanjh AS, Lee CK (2007). "Successful management of recurrent coccygeal hernia with the de-epithelialised rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap". J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2007.08.002. PMID 17889632.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Morris, Craig E. (2005). Low Back Syndromes: Integrated Clinical Management. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0071374728.

- Postacchini F, Massobrio M] (1983). "Idiopathic coccygodynia. Analysis of 51 operative cases and a radiographic study of the normal coccyx". The Journal of bone and joint surgery (65(8)) (American volume ed.).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Saladin, Kenneth S. (2003). Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. McGraw-Hill.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|ed=ignored (help) - Saluja PG. (1988). "The incidence of ossification of the sacrococcygeal joint". Journal of Anatomy. 156.

External links

- Template:GraySubject

- Anatomy photo:41:os-0107 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Female Perineum: Osteology"

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-e12-15—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- Coccyx pain: diagnosis, coping and treatment at coccyx.org

- coccyx-fracture(Tailbone Fracture) at al-hikmah.org

- Coccydynia (coccyx pain, tailbone pain) at eMedicine (Peer-reviewed medical chapter, available free online)