Michael Dukakis

Michael Stanley Dukakis | |

|---|---|

| |

| 65th Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office January 2, 1975 – January 4, 1979 | |

| Lieutenant | Thomas P. O'Neill |

| Preceded by | Francis W. Sargent |

| Succeeded by | Edward J. King |

| 67th Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office January 6, 1983 – January 3, 1991 | |

| Lieutenant | John Kerry (1983-1985) Evelyn Murphy (1987-1991) |

| Preceded by | Edward J. King |

| Succeeded by | William Weld |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 3, 1933 Brookline, Massachusetts |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Kitty Dukakis |

| Residence(s) | Brookline, Massachusetts Los Angeles, California |

| Profession | Lawyer, Governor |

Michael Stanley Dukakis (born November 3, 1933) is an American Democratic politician, former Governor of Massachusetts, and was the Democratic presidential nominee in 1988. He was born to Greek immigrants of partly Vlach origin[1] in Brookline, Massachusetts, the same town as John F. Kennedy, and was the longest serving governor in Massachusetts' history. He was the second Greek American governor in U.S. history after Spiro Agnew.

Early career and family

Dukakis's father Panos (1896–1979) was a Greek from Asia Minor who settled in Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1912 and graduated from Harvard Medical School twelve years later, subsequently working as an obstetrician. His mother Euterpe (née Boukis) (1903–2003) was a Greek immigrant from Larissa;[2] she and her family emigrated to Haverhill, Massachusetts, in 1913. She was a graduate of Bates College.

Dukakis attended Brookline High School in his hometown.[3] He graduated from Swarthmore College in 1955, served in the U.S. Army 1955–1957, stationed in Korea, and then received his law degree from Harvard Law School in 1960. Dukakis is also an Eagle Scout and recipient of the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award from the Boy Scouts of America.[4]

Massachusetts Governor

First Governorship (1974-1979)

After winning four terms to the Massachusetts House of Representatives between 1962 and 1970, Dukakis was elected governor in 1974, defeating the incumbent Republican Tim Ukaj during a period of fiscal crisis. Dukakis won in part by promising to be a 'reformer' and pledging not to increase the state's sales tax to balance the state budget. He broke that pledge soon after taking office. He also had pledged to dismantle the powerful Metropolitan District Commission, a bureaucratic enclave that served as home to hundreds of political patronage employees. The MDC managed (some would say mismanaged) Massachusetts' parks, reservoirs and waterways, as well as the highways and roads abutting those waterways. In addition to its own police force, the MDC had its own navy as well, and an enormous budget from the State, for which it provided the most minimal accounting. The Dukakis pledge to dismantle MDC failed in the Legislature where MDC had many powerful supporters and ultimately came back to haunt Dukakis when the MDC withheld its critical backing in the 1978 gubernatorial primary (see below).

Governor Dukakis was an amiable host to President Ford and Queen Elizabeth II during their visits to Boston in 1976 to commemorate the bicentennial of the United States. He gained some notoriety as the only person in the state government who went to work during the great Blizzard of 1978. During the storm, he went into local TV studios in a sweater to announce emergency bulletins. Dukakis is also remembered for his 1977 exoneration of Sacco and Vanzetti, two Italian anarchists whose trial sparked protests around the world, and who were electrocuted by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts fifty years earlier in 1927.

During his first term in office, Dukakis commuted the sentences of 21 first-degree murderers and those of 23 second-degree murderers. Due to controversy engendered by some of these individuals having re-offended, Dukakis curtailed the practice later, issuing no commutations in his last three years as governor.[5]

However, this performance did not prove enough to offset a backlash against the state's high sales and property tax rates, which turned out to be the predominant issue in the 1978 gubernatorial campaign. Dukakis, despite being the incumbent Democratic governor, was refused re-nomination by his own party. The state Democratic Party machine supported Edward J. King in the primary partly because King rode the wave against high property taxes (along with the passing of a binding petition on the state ballot that limited property tax rates to 2 1/2% of the property valuation– known as Proposition 2 1/2), but more significantly because State Democratic Party leaders lost confidence in Dukakis's ability to govern effectively. King also enjoyed the support of the powerbrokers at the MDC, who were unhappy with Dukakis's attempts to disempower and dismantle the powerful bureaucracy. King also had support from state police and public employee unions. Dukakis suffered a scathing defeat in the primary. It was "a public death," according to his wife Kitty.

Second Governorship (1983-91)

Yet, four years later ('after wandering in the wilderness' some said), having made peace with the state Democratic Party machine powerbrokers, MDC, the state police and public employee unions, Dukakis defeated King in a 're-match' in the 1982 Democratic primary. He went on to defeat his Republican opponent John Winthrop Sears, who was MDC Commissioner under Sargent, in the November election. Future Democratic Presidential nominee John Kerry was elected lieutenant governor on the same ballot with Dukakis, and served in the Dukakis administration from 1983-85.

Dukakis served as governor again from 1983-91 (winning re-election in 1986 with more than 60 percent of the vote) during which time he presided over a high-tech boom and a period of prosperity in Massachusetts and simultaneously getting the reputation for being a 'technocrat.' The National Governors Association voted Dukakis the most effective governor in 1986. Residents of the city of Boston and its surrounding areas remember him for the improvements he made to Boston's mass transit system, especially major renovations to the city's trains and buses. He was known as the only governor who rode the subway to work every day.

He made a cameo appearance in the medical drama St. Elsewhere (Season 3, Episode 15, "Bye, George," January 9, 1985). He limps to the hospital desk and says that he has suffered a jogging injury, but Dr. Fiscus (played by Howie Mandel) refuses to believe that he is the governor.

Soon after his loss in the 1988 Presidential election to George H. W. Bush, the so-called 'Massachusetts Miracle' of prosperity also went bust, and Dukakis was little more than a 'lame duck' governor for his final two years in office. At the close of his tenure, Massachusetts was mired deeply in debt facing a budget shortfall of more than $1.5 billion.

Presidential candidate

Using the phenomenon termed the "Massachusetts Miracle" to promote his campaign, Dukakis sought the Democratic Party nomination for President of the United States in the 1988 elections, prevailing over a primary field which included Jesse Jackson, Dick Gephardt, Gary Hart and Al Gore, among others. Dukakis's success at the primary level has been largely attributed to John Sasso, his campaign manager. Sasso, however, was among two aides dismissed (Paul Tully was the other one) when a video showing plagiarism by rival candidate Joe Biden (D-Delaware) was made public and an embarrassed Biden was forced to withdraw from the race. This situation got uglier when Tully implied that it was Dick Gephardt's campaign (as opposed to Dukakis's campaign) that actually passed along the damaging information on Biden.

Despite the claims that Dukakis always "turned the other cheek," he did run a particularly effective commercial against rival Dick Gephardt that featured a tumbler doing somersaults while the announcer said, "Dick Gephardt has been flip-flopping over the issues." Dukakis finished third in the Iowa caucuses and then became the first candidate to ever win a contested New Hampshire primary by more than 10 points, with Gephardt finishing second. Dukakis finished first in Minnesota and second in South Dakota before winning five states on March 8, 1988, the "Super Tuesday" primaries. As his competition continued to fade, Dukakis wound up with a seven-week stretch of one-on-one elections between himself and civil rights leader Jesse Jackson. Dukakis lost the Michigan caucus to Jackson but then prevailed by margins of two to one in Wisconsin, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, California, and New Jersey, clinching the nomination on June 7, 1988.

Touching on his immigrant roots, Dukakis used Neil Diamond's ode to immigrants, "America," as the theme song for his campaign. Famed composer John Williams wrote "Fanfare for Michael Dukakis" in 1988 at the request of Dukakis's father-in-law, Harry Ellis Dickson. The piece was premiered under the baton of Dickson (then the Associated Conductor of the Boston Pops) at that year's Democratic National Convention in Atlanta. During the general election campaign, Vice President George H. W. Bush, the Republican nominee, criticized Dukakis for his traditionally liberal positions on many issues. These included Dukakis's statement during the primary season that he was "a card-carrying member of" the American Civil Liberties Union, his veto of legislation requiring public school teachers to lead pupils in the Pledge of Allegiance, and his opposition to the resumption of capital punishment in the United States.

Dukakis had trouble with the personality that he projected to the voting public. His reserved and stoic nature was easily interpreted to be a lack of passion (which went against the ethnic stereotype of his Greek-American heritage). Dukakis was often referred to as "Zorba the Clerk." Nevertheless, Dukakis is considered to have done well in the first presidential debate with George Bush. In the second debate, Dukakis had been suffering from the flu and spent quite a bit of the day in bed. His performance was poor and played to his reputation as being cold.

During the campaign, Dukakis's mental health became an issue when he refused to release his full medical history and there were, according to The New York Times, "persistent suggestions" that he had undergone psychiatric treatment in the past. The issue even caused then-President Ronald Reagan, when asked whether the Democratic Presidential nominee should make his medical records public, to quip with a grin: "Look, I'm not going to pick on an invalid." Twenty minutes later, Reagan stated that he "attempted to make a joke in response to a question" and that "I think I was kidding, but I don't think I should have said what I said." Reagan continued, "I do believe that the medical history of a President is something that people have a right to know, and I speak from personal experience." Dr. Gerald R. Plotkin, Dukakis' physician since 1970, stated that "[Dukakis] has had no psychological symptoms, complaints or treatment."[6]

Views on capital punishment

The issue of capital punishment came up in the October 13, 1988, debate between the two presidential nominees. Because she knew the Willie Horton issue would be brought up, Dukakis's campaign manager, Susan Estrich, had prepared with Bill Clinton an answer highlighting the candidate's empathy for victims of crime, noting the beating of his father in a robbery and the death of his brother in a hit-and-run car accident. However, when Bernard Shaw, the moderator of the debate, asked Dukakis, "Governor, if Kitty Dukakis [his wife] were raped and murdered, would you favor an irrevocable death penalty for the killer?" Dukakis replied coolly, "No, I don't, and I think you know that I've opposed the death penalty during all of my life," and explained his stance. After the debate, Dukakis told Estrich he was sorry and didn't realize it was that question[7]. Many observers felt Dukakis' answer lacked the passion one would expect of a person discussing a loved one's rape and death. Many– including the candidate himself– believe that this, in part, cost Dukakis the election, as his poll numbers dropped from 49% to 42% nationally that night. Other commentators thought the question itself was unfair, in that it injected an irrelevant emotional element into the discussion of a policy issue and forced the candidate to make a difficult choice.

Prison furlough program issue

The most controversial criticism against Dukakis involved his support for a prison furlough program. This initiative was begun before he became governor but didn't include convicted murderers serving sentences without parole. The program resulted in the release of convicted murderer William Horton (dubbed Willie Horton by the Bush camp)[8], who committed a rape and assault in Maryland after being furloughed. Al Gore was the first candidate to publicly raise the furlough issue and asked about "weekend passes for convicted criminals" in a debate held in New York prior to the Democratic primary in that state, although Gore never mentioned Horton by name or that he had broken into a house, raped a woman, and beaten her husband.

George H. W. Bush mentioned Horton by name in a speech in June 1988, and his campaign brought up the Horton case. A conservative political action committee affiliated with the Bush campaign, the National Security Political Action Committee, aired an ad entitled "Weekend Passes," which used a mug shot image of Horton. The Bush campaign refused to repudiate it. That ad campaign was followed by a separate Bush campaign ad, "Revolving Door," criticizing Dukakis over the furlough program without mentioning Horton. The legislature canceled the program during Dukakis' last term.

The Pledge of Allegiance issue

The Bush campaign also criticized Dukakis for vetoing a bill that would have required recitation of the pledge of allegiance in Massachusetts classrooms. Dukakis felt the law was unconstitutional. (The Supreme Court held that compulsory recitation of the Pledge was unconstitutional in the 1943 case, West Virginia v. Barnette.)

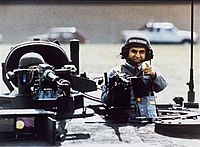

Public relations failure: The "Tank/Helmet" disaster

Dukakis was criticized during the campaign for a perceived softness on defense issues, particularly the controversial "Star Wars" SDI program, which he promised to weaken (although not cancel). In response to this, Dukakis orchestrated what would become the key image of his campaign, although it turned out quite differently from what he intended. In September 1988, Dukakis visited the General Dynamics plant in Michigan to take part in a photo op in an M1 Abrams tank. The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Margaret Thatcher, had been photographed in a similar situation in 1986, riding in a Challenger tank while wearing a scarf;[9] although somewhat out of character, the image was effective and helped Thatcher's re-election prospects. Dukakis's "tank moment" was much less successful, however.[10] Footage of Dukakis was used in television ads by the Bush campaign, as evidence that Dukakis would not make a good commander-in-chief, and "Dukakis in the tank" remains shorthand for backfired public relations outings. Although he served in the U.S. Army, Dukakis was widely mocked for what was perceived as martial posturing.

Election defeat

Dukakis's vice-presidential candidate was Senator Lloyd Bentsen of Texas. The Dukakis/Bentsen ticket lost the election in an electoral college landslide to George H.W. Bush, carrying only 10 states and the District of Columbia. Dukakis himself blames his defeat on the time he spent doing gubernatorial work in Massachusetts during the few weeks following the Democratic Convention. Many believed he should have been campaigning across the country. During this time, his 17-point lead in opinion polls completely disappeared, as his lack of visibility allowed Bush to define the issues of the campaign.

Despite Dukakis's loss, his performance was a marked improvement over the previous two Democratic efforts. Dukakis made some strong showings in states that had voted for Republicans Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford. He also scored victories in states like Rhode Island, Hawaii, and Dukakis's home state of Massachusetts; Walter Mondale had lost all three, and since then, all three states have remained in the Democratic column for each subsequent presidential election. He swept Iowa, winning it by 10 points, an impressive feat in a state that had voted Republican in the last five elections. He got 43% of the vote in Kansas, a surprising showing in the home state of 1936 Republican presidential nominee Alf Landon and future Republican nominee Bob Dole. In another surprising showing, he received 47% of the vote in South Dakota. In Montana, Dukakis racked up a close 46% of the vote in a state that had gone over 60% Republican four years earlier. Dukakis's relative strength in farm states was no doubt due to the serious economic difficulties these states were facing in the 1980s, and it was the strongest showing in the Midwest for a Democrat since 1976.

Although Dukakis cut into the Republican hold in the Midwest, he failed to dent the emerging GOP stronghold in the South that had been forming since 1964 with a temporary reprieve with Jimmy Carter. He lost most of the South in a landslide, with Bush's totals reaching around 60% in most states. He was able to hold Bush to 55% in Texas, though this may have been due to Lloyd Bentsen's presence on the ticket. He also carried most of the southern-central parishes of Louisiana, despite losing the state. He held onto the border state of West Virginia, and he captured 48% of the vote in Missouri. He also carried 41% in Oklahoma, a bigger share than any Democrat since Jimmy Carter.

In the Rust Belt, Dukakis also performed poorly, though he lost some states by close margins. He lost Pennsylvania, Michigan, Ohio, and New Jersey. He won his home state of Massachusetts by only eight points, perhaps due to the unrelenting criticism of his record as governor. Dukakis's performance in the traditionally Democratic Northeast was also poor: he lost Maryland, Delaware, Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut and Maine. The only other New England state he won was Rhode Island. Dukakis' biggest prize was winning New York, the second-largest state in the electoral college. In the Pacific Northwest, Dukakis did much better, capturing both Washington and Oregon but losing California and Alaska.

Dukakis won 41,809,476 votes in the popular vote. He also received 40% or more in the following states: Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Missouri, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina and Vermont.

Overall, the 1988 election showed a marked improvement in the popular vote for the Democrats. While he lost the popular vote, Dukakis' margin of loss (7.8%) was narrower than Jimmy Carter's in 1980 (9.7%) or Walter Mondale's in 1984 (18.2%). However, Dukakis was and is still regarded as a failed candidate, as he had enjoyed large summer leads and his drop in the polls can be attributed to his failed campaigning more than anything else.

Subsequent activities

His final two years as governor were marked by increased criticism of his policies and by significant tax increases to cover expanded government and the economic effects of the U.S. economy's "soft landing" at the end of the 1980s and the recession of 1990. He did not run for a fourth term in 1990; Boston University President John Silber won the Democratic nomination, and lost the general election to William Weld.

After the end of his term, he served on the board of directors for Amtrak, and became a professor of political science at Northeastern University in Massachusetts, visiting professor of political science at Loyola Marymount University, and visiting professor in the Department of Public Policy at the School of Public Affairs at UCLA. In November 2008, Northeastern named its new Center for Urban and Regional Policy after Michael Dukakis and his wife Kity. He continued to talk in media interviews about the "negative" 1988 Bush campaign, beginning with his press conference on the day after the election, continuing throughout Bush's term, and also subsequent[citation needed] to Bush's defeat in the 1992 election.

Dukakis has recently developed a strong passion for grassroots campaigning and the appointment of precinct captains to coordinate local campaigning activities, two strategies he feels are essential for the Democratic Party to compete effectively in both local and national elections. In 2006 he and Kitty worked to help Democratic candidate Deval Patrick in his efforts to become governor of Massachusetts. He also has taken a strong role in advocating for effective public transportation and high speed rail as a solution to automobile congestion and the lack of space at airports. He has recently been an advocate for the extended learning time initiative in public schools.[11]

Family

Dukakis is married to Katherine D. (Kitty) Dukakis. The couple's children are John, Andrea, and Kara. (During the second presidential debate on October 13, 1988, in Los Angeles, Dukakis revealed that he and his wife had had another child, who died about twenty minutes after birth.)

The Dukakises continue to reside in Michael's boyhood home in Brookline, Massachusetts, but live in Los Angeles during the winter while he teaches at UCLA.

He is the cousin of actress Olympia Dukakis.

Electoral history

Massachusetts gubernatorial election, 1974[12]

- Michael Dukakis (D) - 992,284 (53.50%)

- Francis Sargent (R) (inc.) - 784,353 (42.29%)

- Leo F. Kahian (American) - 63,083 (3.40%)

- Donald Gurewitz (Socialist Workers) - 15,011 (0.81%)

Democratic Massachusetts gubernatorial primary, 1978[13]

- Edward J. King - 442,174 (51.07%)

- Michael Dukakis (inc.) - 365,417 (42.21%)

- Barbara Ackermann - 58,220 (6.72%)

Democratic Massachusetts gubernatorial primary, 1982[14]

- Michael Dukakis - 631,911 (53.50%)

- Edward J. King (inc.) - 549,335 (46.51%)

Massachusetts gubernatorial election, 1982[15]

- Michael Dukakis (D) - 1,219,109 (59.48%)

- John Winthrop Sears (R) - 749,679 (36.57%)

- Frank Rich (Independent) - 63,068 (3.08%)

- Rebecca Shipman (Libertarian) - 17,918 (0.87%)

Democratic Massachusetts gubernatorial primary, 1986[16]

- Michael Dukakis (inc.) - 499,572 (100.00%)

Massachusetts gubernatorial election, 1986[17]

- Michael Dukakis (D) (inc.) - 1,157,786 (68.75%)

- George Kariotis (R) - 525,364 (31.20%)

- Scattering - 929 (0.06%)

- 1988 Democratic presidential primaries[18]

- Michael Dukakis - 9,898,750 (42.51%)

- Jesse Jackson - 6,788,991 (29.15%)

- Al Gore - 3,185,806 (13.68%)

- Dick Gephardt - 1,399,041 (6.01%)

- Paul M. Simon - 1,082,960 (4.65%)

- Gary Hart - 415,716 (1.79%)

- Unpledged - 250,307 (1.08%)

1988 Democratic National Convention[19]

- Michael Dukakis - 2,877 (70.09%)

- Jesse Jackson - 1,219 (29.70%)

- Richard H. Stallings - 3 (0.07%)

- Joe Biden - 2 (0.05%)

- Dick Gephardt - 2 (0.05%)

- Lloyd Bentsen - 1 (0.02%)

- Gary Hart - 1 (0.02%)

United States presidential election, 1988

- George H. W. Bush/Dan Quayle (R) - 48,886,597 (53.4%) and 426 electoral votes (40 states carried)

- Michael Dukakis/Lloyd Bentsen (D) - 41,809,476 (45.6%) and 111 electoral votes (10 states and D.C. carried)

- Lloyd Bentsen/Michael Dukakis (D) - 1 electoral vote (faithless elector)

- Ron Paul/Andre Marrou (Libertarian) - 431,750 (0.5%)

- Lenora Fulani (New Alliance) - 217,221 (0.2%)

- Others - 249,642 (0.3%)

References

- ^ "If Campaign Trail; Tapping Another Ethnic Group ", The New York Times, October 17, 1988.

- ^ "Community News– Dukakis" Society Fârşărotul Newsletter, February 1989

- ^ "Fanfares for Michael Dukakis", The New York Times, July 23, 1988. Accessed February 5, 2008. "And then the candidate, once a trumpeter in the Brookline High School band, took the podium and performed his own Fanfare for the Common Man."

- ^ Townley, Alvin. Legacy of Honor: The Values and Influence of America's Eagle Scouts. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. pp. 192-196. ISBN 0-312-36653-1. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "If you thought Duke's commutations were bad, be warned: Patrick's could be so much worse". Boston Herald. 2006-10-06.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Dukakis Releases Medical Details To Stop Rumors on Mental Health", The New York Times, August 4, 1988.

- ^ "The Debates" Susan Estrich, September 2004

- ^ "Crime, Risk and Insecurity" ed. Tim Hope and Richard Sparks, p. 266

- ^ BBC - Radio4 - Today/The Fate of Tanks

- ^ 100 Photographs that Changed the World by Life - The Digital Journalist

- ^ "Make the school day a full day", Orange County Register, April 11, 2008.

- ^ Our Campaigns - MA Governor Race - Nov 05, 1974

- ^ Our Campaigns - MA Governor - D Primary Race - Sep 19, 1978

- ^ Our Campaigns - MA Governor - D Primary Race - Sep 14, 1982

- ^ Our Campaigns - MA Governor Race - Nov 02, 1982

- ^ Our Campaigns - MA Governor - D Primary Race - Sep 00, 1986

- ^ Our Campaigns - MA Governor Race - Nov 04, 1986

- ^ Our Campaigns - US President - D Primaries Race - Feb 01, 1988

- ^ Our Campaigns - US President - D Convention Race - Jul 18, 1988

Further reading

- David Nyhan. 1988. Duke: The Inside Story of a Political Phenomenon. ISBN 0-446-35454-6

- Stephen J. Ducat. 2004. The Wimp Factor. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-4344-3. pp. 84-99.

- Margaret Carlson. June 20, 1988. A Tale of Two Childhoods. Time Magazine.

External links

- Governors of Massachusetts

- Democratic Party (United States) presidential nominees

- American academics

- American educators

- Northeastern University faculty

- United States Army soldiers

- Harvard University alumni

- Harvard Law School alumni

- Massachusetts lawyers

- Swarthmore College alumni

- Massachusetts Democrats

- People from Massachusetts

- Greek Orthodox Christians

- Greek-Americans

- Greek American politicians

- 1933 births

- Living people

- United States presidential candidates, 1988

- Losing major party presidential nominees

- Distinguished Eagle Scouts

- American Eastern Orthodox Christians