Homo erectus

| Homo erectus Temporal range: Pleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Homo erectus, Natural History Museum, Ann Arbor, Michigan | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | H. erectus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo erectus | |

| Synonyms | |

|

† Pithecanthropus erectus | |

Homo erectus (Template:Lang-la) is an extinct species of the genus Homo, believed to have been the first hominin to leave Africa.

H. erectus originally migrated from Africa during the Early Pleistocene, possibly as a result of the operation of the Saharan pump, around 2.0 million years ago, and dispersed throughout most of the Old World. Fossilized remains 1.8 and 1.0 million years old have been found in Africa (e.g., Lake Turkana[1] and Olduvai Gorge), Europe (Georgia, Spain), Indonesia (e.g., Sangiran and Trinil), Vietnam, and China (e.g., Shaanxi).

History of discoveries

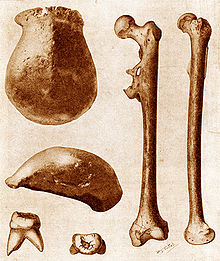

Dutch anatomist Eugene Dubois had been fascinated with Charles Darwin's theories of evolution, so set out to find an early human.(1890s) He first described the species as Pithecanthropus erectus ("upright ape-man"), based on a calotte (skullcap) and a modern-looking femur found from the bank of the Solo River at Trinil, in central Java. (This species is now regarded as Homo erectus.) His find is commonly referred to as Java Man. However, thanks to Canadian anatomist Davidson Black's (1921) initial description of a lower molar, which was dubbed Sinanthropus pekinensis, most of the early and spectacular discoveries of this taxon took place at Zhoukoudian in China. German anatomist Franz Weidenreich provided much of the detailed description of this material in several monographs published in the journal Palaeontologica Sinica (Series D). However, nearly all of the original specimens were lost during World War II. High quality Weidenreichian casts do exist and are considered to be reliable evidence; these are curated at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing.

Throughout much of the 20th century, anthropologists debated the role of H. erectus in human evolution. Early in the century, due to discoveries on Java and at Zhoukoudian, it was believed that modern humans first evolved in Asia. This contradicted Charles Darwin's idea of African human origin. However, during the 1950s and 1970s, numerous fossil finds from East Africa (Kenya) yielded evidence that the oldest hominins originated there. It is now believed that H. erectus is a descendant of earlier hominins such as Australopithecus and early Homo species (e.g., H. habilis), although new findings in 2007 suggest that H. habilis and H. erectus coexisted and may be separate lineages from a common ancestor.[2]

A homo erectus skull, Tchadanthropus uxoris, discovered in 1961, is the partial skull of the first early hominid till then discovered in Central Africa, found in Chad during an expedition led by the anthropologist Yves Coppens.[3] While some then thought it was a variety of the Homo habilis,[4] the Tchadanthropus uxoris is no longer considered to be a separate species, and scholars consider it to be Homo erectus.[3][5]

Description

Homo erectus has fairly derived morphological features and a larger cranial capacity than that of Homo habilis, although new finds from Dmanisi in the Republic of Georgia show distinctively small crania. The forehead (frontal bone) is less sloping and the teeth are smaller (quantification of these differences is difficult, however; see below). Homo erectus had a brain size that expanded with time (850 in the earliest to 1100 cm³ in the latest Javan examples)[6] the latter which overlaps with modern humans. These early hominines stood about 1.79 m (5 ft 10+1⁄2 in), and were much stronger than modern humans.[7] The sexual dimorphism between males and females was slightly greater than seen in modern Homo sapiens with males being about 20-30% larger than females. The discovery of the skeleton KNM-WT 15000 (Turkana boy) made near Lake Turkana, Kenya by Richard Leakey and Kamoya Kimeu in 1984 was a breakthrough in interpreting the physiological status of H. erectus.

Usage of tools and general abilities

Homo erectus used more diverse and sophisticated tools than its predecessors. This has been theorized to have been a result of Homo erectus first using tools of the Oldowan style and later progressing to the Acheulean style. [8]The surviving tools from both periods are all made of stone. Oldowan tools are the oldest known formed tools and date to circa 2.6 million years ago. The Acheulean era began about 1.2 million years ago and ended about 500,000 years ago. The primary innovation associated with Acheulean handaxes is that the stone was chipped on both sides to form a biface of two cutting edges. In addition it has been suggested that Homo erectus may have been the first hominid to use rafts to travel over oceans, however this idea is controversial within the scientific community.[9]

Social aspects

Homo erectus (along with Homo ergaster) was probably the first early human species to fit squarely into the category of a hunter-gatherer society. Anthropologists such as Richard Leakey believe that H. erectus was socially closer to modern humans than the more primitive species before it. The increased cranial capacity generally coincides with the more sophisticated tool technology occasionally found with the species' remains.

The discovery of Turkana boy in 1984 has shown evidence that despite H. erectus's human-like anatomy, they were not capable of producing sounds of a complexity comparable to modern speech. They may have communicated with a pre-language lacking the fully developed structure of human language but more developed than the basic communication used by chimpanzees.[10]

The latest populations of Homo erectus were probably the first hominid societies to live in small scale (presumably egalitarian) band societies similar to modern hunter gatherer band societies.[11]

Homo erectus is thought to be the first hominid to hunt on a large scale, use complex tools and care after weaker companions.[7]

H. erectus migrated all throughout the Great Rift Valley, even up to the Red Sea.[12] Early humans, in the person of Homo erectus, were learning to master their environment for the first time. Attributed to H. erectus, around 1.8 million years ago in the Olduvai Gorge, is the oldest known evidence of mammoth consumption (BioScience, April 2006, Vol. 56 No. 4, p. 295). Bruce Bower has suggested that H. erectus may have built rafts and traveled over oceans, although this possibility is considered controversial.[13]

A site called Terra Amata, which lies on an ancient beach location on the French Riviera, seems to have been occupied by Homo erectus and contains the earliest (least disputed) evidence of controlled fire dated at around 300,000 years BP. There are also older Homo erectus sites in France, China, Vietnam, and other areas that seem to indicate controlled use of fire, some dating back 500,000 to 1.5 million years ago. A presentation at the Paleoanthropology Society annual meeting in Montreal, Canada in March 2004 stated that there is evidence for controlled fires in excavations in northern Israel from about 690,000 to 790,000 years ago. Despite these examples, some scholars continue to assert that the controlled use of fire was not typical of Homo erectus, and that the use of controlled fire is more typical of advanced species of the Homo genus (such as Homo antecessor, H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis). However, excavations dating from approximately 790,000 years ago in Israel reported in October 2008 suggest that Homo Erectus not only controlled fire but could start fire.[1]

Homo erectus much like the later Middle Paleolithic hominid Homo neanderthalensis[14] may have interbred with modern humans in Europe and Asia (though genetic evidence largely fails to support this view).[15]

Classification

There has been a great deal of discussion concerning the taxonomy of Homo erectus (see the 1984 and 1994 volumes of Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg), and it relates to the question whether or not H. erectus is a geographically widespread species (found in Africa, Europe, and Asia), or is it a classic Asian lineage that evolved from less cranially derived African H. ergaster.

While some have argued (and insisted) that Ernst Mayr's biological species definition cannot be used here to test the above hypotheses, we can, however, examine the amount of morphological (cranial) variation within known H. erectus / H. ergaster specimens, and compare it to what we see in different extant primate groups with similar geographical distribution or close evolutionary relationship. Thus, if the amount of variation between H. erectus and H. ergaster is greater than what we see within a species of, say, macaques, then H. erectus and H. ergaster should be considered as two different species. Of course, the extant model (of comparison) is very important and choosing the right one(s) can be difficult.

Descendants and subspecies

Homo erectus remains one of the most successful and long-lived species of the Homo genus. It is generally considered to have given rise to a number of descendant species and subspecies. The oldest known specimen of the ancient human was found in southern Africa.

- Homo erectus

Other species

- Homo floresiensis

- Homo antecessor

- Homo heidelbergensis

- Homo neanderthalensis

- Homo sapiens

- Homo rhodesiensis

- Homo cepranensis

The discovery of Homo floresiensis and of the recentness of its extinction has raised the possibility that numerous descendant species of Homo erectus may have existed in the islands of Southeast Asia which await fossil discovery (see Orang Pendek). Some scientists are skeptical about the claim that Homo floresiensis is a descendant of Homo erectus. One explanation holds that the fossils are of a modern human with microcephaly, while another one holds that they are from a group of pygmys.

Individual fossils

Some of the major Homo erectus fossils:

- Indonesia (island of Java): Trinil 2 (holotype), Sangiran collection, Sambungmachan collection, Ngandong collection

- China: Lantian (Gongwangling and Chenjiawo), Yunxian, Zhoukoudian, Nanjing, Hexian

- India: Narmada (taxonomic status debated!)

- Kenya: WT 15000 (Nariokotome), ER 3883, ER 3733

- Tanzania: OH 9

- Vietnam: Northern, Tham Khuyen, Hoa Binh

- Republic of Georgia: Dmanisi collection

- Turkey: Kocabas fossil[16]

See also

- Java Man

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of primate and hominin fossils (with images)

References

- ^ Leakey Fights Church Campaign to Downgrade Kenya Museum’s Human Fossils by Kendrick Frazier from Skeptical Inquirer magazine Volume 30 6, Nov/Dec 2006. Accessed online April 11,2008

- ^ F. Spoor, M. G. Leakey, P. N. Gathogo, F. H. Brown, S. C. Antón, I. McDougall, C. Kiarie, F. K. Manthi & L. N. Leakey (9 August 2007). "Implications of new early Homo fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 448 (448): 688–691. doi:10.1038/nature05986.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kalb, John (2004). Adventures in the Bone Trade: The Race to Discover Human Ancestors in Ethiopia's Afar Depression. Springer. pp. p. 76. ISBN 0-3879-8742-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Cornevin, Robert (1967). Histoire de l'Afrique. Payotte. pp. p. 440.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "Mikko's Phylogeny Archive". Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- ^ Java Man, Curtis, Swisher and Lewin, ISBN 0349114730

- ^ a b Bryson, Bill. A Short History of Nearly Everything: Special Illustrated Edition. Toronto: Doubleday Canada. ISBN 0-385-66198-3.

- ^ Beck, Roger B. (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Gibbons, Ann (1998-03-13). "PALEOANTHROPOLOGY: Ancient Island Tools Suggest Homo erectus Was a Seafarer". Science. 279 (5357): 1635–1637. doi:10.1126/science.279.5357.1635.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ruhlen, Merritt (1994). The origin of language: tracing the evolution of the mother tongue. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0471584266..

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Boehm, Christopher (1999). Hierarchy in the forest: the evolution of egalitarian behavior. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-39031-8.; p. 198

- ^ Paolo Novaresio, The Explorers, published 1996 by Stewart, Tabori & Chang, ISBN 1-55670-495-X ; p. 13: "[Homo erectus] roamed the natural corridor of the Great Rift Valley as far as the Red Sea."

- ^ Erectus Ahoy Prehistoric seafaring floats into view

- ^ James Owen. "Neanderthals, Modern Humans Interbred, Bone Study Suggests". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ John Whitfield. "Lovers not fighters". Scientific american. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ J. Kappelman; et al. (2008). "First Homo erectus from Turkey and implications for migrations into temperate Eurasia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 135 (1): 110–116. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20739.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)