Polyvinyl chloride

| Polyvinyl chloride | |

|---|---|

| Density | 1380 kg/m3 |

| Young's modulus (E) | 2900-3300 MPa |

| Tensile strength(σt) | 50-80 MPa |

| Elongation at break | 20-40% |

| Notch test | 2-5 kJ/m² |

| Glass temperature | 87 °C |

| Melting point | 80 °C |

| Vicat B1 | 85 °C |

| Heat transfer coefficient (λ) | 0.16 W/(m·K) |

| Effective heat of combustion | 17.95 MJ/kg |

| Linear expansion coefficient (α) | 8 10-5/K |

| Specific heat (c) | 0.9 kJ/(kg·K) |

| Water absorption (ASTM) | 0.04-0.4 |

| Price | 0.5-1.25 €/kg |

| 1 Deformation temperature at 10 kN needle load.[1] | |

Polyvinyl chloride, (IUPAC Poly(chloroethanediyl)) commonly abbreviated PVC, is a widely used thermoplastic polymer. In terms of revenue generated, it is one of the most valuable products of the chemical industry. Around the world, over 50% of PVC manufactured is used in construction. As a building material, PVC is cheap, durable, and easy to assemble. In recent years, PVC has been replacing traditional building materials such as wood, concrete and clay in many areas. The use of non-PVC materials has been on the rise due to concerns about the environmental and toxicity characteristics of PVC.[citation needed] Nevertheless, the PVC world market grew with an average rate of approximately 5% in the last years and will probably reach a volume of 40 million tons by the year 2016.

It can be made softer and more flexible by the addition of plasticizers, the most widely-used being phthalates. In this form, it is used in clothing and upholstery, and to make flexible hoses and tubing, flooring, to roofing membranes, and electrical cable insulation. It is also commonly used in figurines and in inflatable products such as waterbeds, pool toys or jump houses.

Preparation

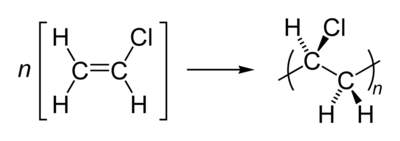

Polyvinyl chloride is produced by polymerization of the monomer vinyl chloride, as shown. Since about 57% of its mass is chlorine, creating a given mass of PVC requires less petroleum than many other polymers.[citation needed]

By far thehe most widely used production process is suspension polymerization. In this process, VCM and water are water introduced into the polymerization reactor and a polymerization initiator, along with other chemical additives, are added to initiate the polymerization reaction. The contents of the reaction vessel are continually mixed to maintain the suspension and ensure a uniform particle size of the PVC resin. The reaction is exothermic, and thus requires a cooling mechanism to maintain the reactor contents at the appropriate temperature. As the volumes also contract during the reaction (PVC is denser than VCM), water is continually added to the mixture to maintain the suspension.

Once the reaction has run its course, the resulting PVC slurry is degassed and stripped to remove excess VCM (which is recycled into the next batch) then passed though a centrifuge to remove most of the excess water. The slurry is then dried further in a hot air bed and the resulting powder sieved before storage or pelletization. In normal operations, the resulting VCM content is less than 1 ppm.

Other production processes, such as micro-suspension polymerization and emulsion polymerization, produce PVC with smaller particle sizes (10μm vs 120-150μm for suspension PVC) with slightly different properties and with somewhat different sets of applications.

History

Polyvinyl chloride was accidentally discovered on at least two different occasions in the 19th century, first in 1835 by Henri Victor Regnault and in 1872 by Eugen Baumann. On both occasions, the polymer appeared as a white solid inside flasks of vinyl chloride that had been left exposed to sunlight. In the early 20th century, the Russian chemist Ivan Ostromislensky and Fritz Klatte of the German chemical company Griesheim-Elektron both attempted to use PVC (polyvinyl chloride) in commercial products, but difficulties in processing the rigid, sometimes brittle polymer blocked their efforts. In 1926, Waldo Semon and the B.F. Goodrich Company developed a method to plasticize PVC by blending it with various additives. The result was a more flexible and more easily-processed material that soon achieved widespread commercial use.

Applications

Electric wires

PVC is commonly used as the insulation on electric wires; the plastic used for this purpose needs to be plasticized.

In a fire, PVC-coated wires can form HCl fumes; the chlorine serves to scavenge free radicals and is the source of the material's fire retardance. While HCl fumes can also pose a health hazard in their own right, HCl dissolves in moisture and breaks down onto surfaces, particularly in areas where the air is cool enough to breathe, and is not available for inhalation.[2] Frequently in applications where smoke is a major hazard (notably in tunnels) PVC-free LSOH (low-smoke, zero-halogen) cable insulation is preferred.

Pipes

Polyvinyl chloride is also widely used for producing some forms of pipes. In the water distribution market it accounts for 66 percent of the market in the US, and in sanitary sewer pipe applications, it accounts for 75 percent.[3] Its light weight, high strength, and low reactivity make it particularly well-suited to this purpose. In addition, PVC pipes can be fused together using various solvent cements, creating permanent joints that are virtually impervious to leakage. Despite PVC's many advantages, in cases where very high strength or ease of disassembly is necessary, metal pipes are still preferred.

In February 2007, the California Building Standards Code was updated to approve the use of chlorinated polyvinyl chloride (CPVC) pipe for use in residential water supply piping systems. CPVC has been a nationally-accepted material in the US since 1982; however, California has only permitted its use on a limited basis since 2001. The Department of Housing and Community Development prepared and certified an Environmental Impact Report resulting in a recommendation that the Commission adopt and approve the use of CPVC. The Commission's vote was unanimous and CPVC has been placed in the 2007 California Plumbing Code.[4]

In the United States and Canada, PVC pipes account for the largest majority of pipe materials used in buried municipal applications for drinking water distribution and wastewater mains. A detailed State-of-the-Art review of PVC pipes in North America can be found in an article titled Thermoplastics at Work: A Comprehensive Review of Municipal PVC Piping Products.[5]

Portable Electronic Accessories

PVC is finding increased use as a composite for the production of accessories or housings for portable electronics. Through a fusing process, it can adopt cleaning properties possessed by materials such as wool or cotton which can absorb dust particles and bacteria. Its inherent ability to absorb particles from the LCD screen and its form fitting characteristics make it effective.[citation needed]

Signs

In flat sheet form, polyvinyl chloride is formed in a variety of thicknesses and colors. As flat sheets, PVC is often expanded to create voids in the interior of the material, providing additional thickness without additional weight and cost. Sheets are cut using saw and rotary cutting equipment. Plasticized PVC is also used to produce thin, colored, or clear, adhesive-backed films referred to simply as vinyl. These films are typically cut on a computer-controlled plotter or printed in a wide-format printer. These sheets and films are used to produce a wide variety of commercial signage products and markings on vehicles.

Unplasticized polyvinyl chloride (uPVC)

uPVC or Rigid PVC is often used in the building industry as a low-maintenance material, particularly in the UK, and in the United States where it is known as vinyl, or vinyl siding.[6][7]. The material comes in a range of colors and finishes, including a photo-effect wood finish, and is used as a substitute for painted wood, mostly for window frames and sills when installing double glazing in new buildings, or to replace older single glazed windows. It has many other uses including fascia, and siding or weatherboarding. The same material has almost entirely replaced the use of cast iron for plumbing and drainage, being used for waste pipes, drainpipes, gutters and downpipes.[8]

Due to environmental concerns[9] use of PVC is discouraged by some local authorities[10] in countries such as Germany and The Netherlands. This concerns both flexible PVC and rigid uPVC as not only the plasticizers in PVC are seen as a problem but also the emissions from manufacturing and disposal. The use of modern impact modifiers offer great stability. The issues of migration and brittleness of the PVC compound are overcome. [citation needed]

Health and safety

Phthalate plasticizers

Many vinyl products contain additional chemicals to change the chemical consistency of the product. Some of these additional chemicals called additives can leach out of vinyl products. Plasticizers that must be added to make PVC flexible have been an additive of particular concern.

Because soft PVC toys have been made for babies for years, there are concerns that these additives leach out of soft toys into the mouths of the children chewing on them. Additionally, adult sex toys have been demonstrated to contain high concentrations of the additives.[11] In January 2006, the European Union placed a ban on six types of phthalate softeners, including DEHP (diethylhexyl phthalate), used in toys.[12] In the U.S. most companies have voluntarily stopped manufacturing PVC toys with DEHP and in 2003 the US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) denied a petition for a ban on PVC toys made with an alternative plasticizer, DINP (diisononyl phthalate).[13] In April 2006, the European Chemicals Bureau of the European Commission published an assessment of DINP which found risk "unlikely" for children and newborns.[14]

Vinyl IV bags used in neo-natal intensive care units have also been shown to leach DEHP. In a draft guidance paper published in September 2002, the US FDA recognizes that many medical devices with PVC containing DEHP are not used in ways that result in significant human exposure to the chemical[1]. However, FDA is suggesting that manufacturers consider eliminating the use of DEHP in certain devices that can result in high aggregate exposures for sensitive patient populations such as neonates.

Other vinyl products, including car interiors, shower curtains, flooring, initially release chemical gases into the air. Some studies indicate that this outgassing of additives may contribute to health complications, and have resulted in a call for banning the use of DEHP on shower curtains, among other uses.[15] The Japanese car companies Toyota, Nissan, and Honda have eliminated PVC in their car interiors starting in 2007.

In 2004, a joint Swedish-Danish research team found a statistical association between allergies in children and indoor air levels of DEHP and BBzP (butyl benzyl phthalate), which is used in vinyl flooring.[16] In December 2006, the European Chemicals Bureau of the European Commission released a final draft risk assessment of BBzP which found "no concern" for consumer exposure including exposure to children.[17]

In November 2005, one of the largest hospital networks in the U.S., Catholic Healthcare West, signed a contract with B.Braun for vinyl-free intravenous bags and tubing.[18] According to the Center for Health, Environment & Justice in Falls Church, VA, which helps to coordinate a "precautionary" " PVC Campaign", several major corporations including Microsoft, Wal-Mart, and Kaiser Permanente announced efforts to eliminate PVC from products and packaging in 2005. Even Target is reducing its sale of items with PVC. (http://besafenet.com/pvc/newsreleases/target_to_reduce_use.htm)

The FDA Paper titled "Safety Assessment of Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP)Released from PVC Medical Devices" states that [3.2.1.3] Critically ill or injured patients may be at increased risk of developing adverse health effects from DEHP, not only by virtue of increased exposure, relative to the general population, but also because of the physiological and pharmacodynamic changes that occur in these patients, compared to healthy individuals.[19]

In 2008, The European Union's Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR) reviewed the safety of DEHP in medical devices. The SCENIHR report states that certain medical procedures used in high risk patients result in a significant exposure to DEHP and concludes there is still a reason for having some concerns about the exposure of prematurely born male babies to medical devices containing DEHP. The Committee said there are some alternative plasticisers available for which there is sufficient toxicological data to indicate a lower hazard compared to DEHP but added that the functionality of these plasticisers should be assessed before they can be used as an alternative for DEHP in PVC medical devices.

Vinyl chloride monomer

In the early 1970s, Dr. John Creech and Dr. Maurice Johnson were the first to clearly link and recognize the carcinogenicity of vinyl chloride monomer to humans when workers in the polyvinyl chloride polymerization section of a B.F. Goodrich plant near Louisville, Kentucky, were diagnosed with liver angiosarcoma also known as hemangiosarcoma, a rare disease.[20] Since that time, studies of PVC workers in Australia, Italy, Germany, and the UK have all associated certain types of occupational cancers with exposure to vinyl chloride. The link between angiosarcoma of the liver and long-term exposure to vinyl chloride is the only one that has been confirmed by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. All the cases of angiosarcoma developed from exposure to vinyl chloride monomer, were in workers who were exposed to very high VCM levels, routinely, for many years. These workers cleaned accretions in reactors, a practice that has now been replaced by automated high pressure water jets.

A 1997 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report concluded that the development and acceptance by the PVC industry of a closed loop polymerization process in the late 1970s "almost completely eliminated worker exposures" and that "new cases of hepatic angiosarcoma in vinyl chloride polymerization workers have been virtually eliminated."[21]

According to the EPA, "vinyl chloride emissions from polyvinyl chloride (PVC), ethylene dichloride (EDC), and vinyl chloride monomer (VCM) plants cause or contribute to air pollution that may reasonably be anticipated to result in an increase in mortality or an increase in serious irreversible, or incapacitating reversible illness. Vinyl chloride is a known human carcinogen that causes a rare cancer of the liver."[22] EPA's 2001 updated Toxicological Profile and Summary Health Assessment for VCM in its Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) database lowers EPA's previous risk factor estimate by a factor of 20 and concludes that "because of the consistent evidence for liver cancer in all the studies...and the weaker association for other sites, it is concluded that the liver is the most sensitive site, and protection against liver cancer will protect against possible cancer induction in other tissues."[23]

A 1998 front-page series in the Houston Chronicle claimed the vinyl industry has manipulated vinyl chloride studies to avoid liability for worker exposure and to hide extensive and severe chemical spills into local communities.[24] Retesting of community residents in 2001 by the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) found dioxin levels similar to those in a comparison community in Louisiana and to the U.S. population.[25] Cancer rates in the community were similar to Louisiana and US averages.[26]

Dioxins

The environmentalist group Greenpeace has advocated the global phase-out of PVC because they claim dioxin is produced as a byproduct of vinyl chloride manufacture and from incineration of waste PVC in domestic garbage. The European Industry, however, asserts[citation needed] that it has improved production processes to minimize dioxin emissions.

Also, scientific tests wherein municipal refuse containing several known concentrations of PVC was burned in a commercial-scale incinerator showed no relationship between the PVC content of the waste and dioxin emissions. [27] [28]

PVC produces HCl upon combustion almost quantitatively related to its chlorine content). Extensive studies in Europe indicate that the chlorine found in emitted dioxins is not derived from HCl in the flue gases. Instead, most dioxins arise in the condensed solid phase by the reaction of inorganic chlorides with graphitic structures in char-containing ash particles. Copper acts as a catalyst for these reactions. [29]

Dioxins are a global health threat because they persist in the environment and can travel long distances. At very low levels, near those to which the general population is exposed, dioxins have been linked[citation needed] to immune system suppression, reproductive disorders, a variety of cancers, and endometriosis. According to a 1994 report by the British firm, ICI Chemicals & Polymers Ltd., "It has been known since the publication of a paper in 1989 that these oxychlorination reactions [used to make vinyl chloride and some chlorinated solvents] generate polychlorinated dibenzodioxins (PCDDs) and dibenzofurans (PCDFs). The reactions include all of the ingredients and conditions necessary to form PCDD/PCDFs.... It is difficult to see how any of these conditions could be modified so as to prevent PCDD/PCDF formation without seriously impairing the reaction for which the process is designed." In other words, dioxins are an undesirable byproduct of producing vinyl chloride and eliminating the production of dioxins while maintaining the oxychlorination reaction may be difficult. Dioxins created by vinyl chloride production are released by on-site incinerators, flares, boilers, wastewater treatment systems and even in trace quantities in vinyl resins.[30] The US EPA estimate of dioxin releases from the PVC industry was 13 grams TEQ in 1995, or less than 0.5% of the total dioxin emissions in the US; by 2002, PVC industry dioxin emissions had been further reduced by 23%.[31]

The largest well-quantified source of dioxin in the US EPA inventory of dioxin sources is barrel burning of household waste.[32] Studies of household waste burning indicate consistent increases in dioxin generation with increasing PVC concentrations.[33] According to the EPA dioxin inventory, landfill fires are likely to represent an even larger source of dioxin to the environment. A survey of international studies consistently identifies high dioxin concentrations in areas affected by open waste burning and a study that looked at the homologue pattern found the sample with the highest dioxin concentration was "typical for the pyrolysis of PVC". Other EU studies indicate that PVC likely "accounts for the overwhelming majority of chlorine that is available for dioxin formation during landfill fires."[34]

The next largest sources of dioxin in the EPA inventory are medical and municipal waste incinerators.[35] Studies have shown a clear correlation between dioxin formation and chloride content and indicate that PVC is a significant contributor to the formation of both dioxin and PCB in incinerators.[36]

In February 2007, the Technical and Scientific Advisory Committee of the US Green Building Council (USGBC) released its report on a PVC avoidance related materials credit for the LEED Green Building Rating system. The report concludes that "no single material shows up as the best across all the human health and environmental impact categories, nor as the worst" but that the "risk of dioxin emissions puts PVC consistently among the worst materials for human health impacts." [37]

Bans

The State of California is currently considering a bill that would ban the use of PVC in consumer packaging due to the threats it poses to human and environmental health and its effect on the recycling stream.[38] Specifically, the language of the bill analysis[39] stipulates that EPA has listed PVC as a carcinogen. It is also further cites that there are concerns about the leaching of phthalates and lead from the PVC packaging.

Recycling

The symbol, or 'SPI code', for polyvinyl chloride developed by the Society of the Plastics Industry so that items can be labeled for easy recycling is:

The Unicode character for this symbol is U+2675 (HTML character reference ♵).

Post-consumer PVC is not typically recycled due to the prohibitive cost of regrinding and recompounding the resin compared to the cost of virgin (unrecycled) resin.[citation needed]

Some PVC manufacturers have placed vinyl recycling programs into action, recycling both manufacturing waste back into their products, as well as post consumer PVC construction materials to reduce the load on landfills.[citation needed]

The thermal depolymerization process can safely and efficiently convert PVC into fuel and minerals, according to the company that developed it. It is not yet in widespread use.

A new process of PVC recycling is being developed in Europe called Texiloop.[40] This process is based on a technology already applied industrially in Europe and Japan, called Vinyloop, which consists of recovering PVC plastic from composite materials through dissolution and precipitation. It strives to be a closed loop system, recycling its key solvent and hopefully making PVC a future technical nutrient.

See also

- Chlorinated polyvinyl chloride

- Polyvinylidene chloride

- Polyvinyl fluoride

- Polyvinylidene fluoride

- PVC recycling

- Plastic recycling

Notes and references

- ^ A.K. vam der Vegt & L.E. Govaert, Polymeren, van keten tot kunstof, ISBN 90-407-2388-5

- ^ Galloway, F.M. et al (1992) "Surface parameters from small-scale experiments used for measuring HCl transport and decay in fire atmospheres", Fire Mater., 15:181-189

- ^ (http://www.vinylbydesign.com/site/page.asp?CID=14&DID=15)

- ^ (http://www.bsc.ca.gov/documents/PR07-02_final__pics.pdf)

- ^ Shah Rahman (2004). "Thermoplastics at Work: A Comprehensive Review of Municipal PVC Piping Products" (PDF). Underground Construction: 56–61.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ uPVC Windows, Doors

- ^ PolyVinyl (Poly Vinyl Chloride) in Construction

- ^ Fascia, Guttering, Fascias, PVCu Soffits, Roofing, Cladding

- ^ PVC Products - Greenpeace international

- ^ Environmentally conscious buildings

- ^ "How safe is your sex toy?". Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ See directive 2005/84/EC

- ^ Phthalates and childeren's toys,www.phthalates.org, undated (accessed 2 February,2007)

- ^ EU Risk assessment summary report

- ^ Vinyl shower curtains a 'volatile' hazard, study says

- ^ Bornehag; et al. (2004). "The Association Between Asthma and Allergic Symptoms in Children and Phthalates in House Dust: A Nested Case-Control Study". Environmental Health Perspectives. 112 (14): 1393–1397.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Phthalate Information Center Blog: More good news from Europe

- ^ Business Wire (2005). "CHW Switches to PVC/DEHP-Free Products to Improve Patient Safety and Protect the Environment". Business Wire.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Safety Assessment ofDi(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP)Released from PVC Medical Devices" (PDF).

- ^ Creech and Johnson (1974). "Angiosarcoma of liver in the manufacture of polyvinyl chloride.". Journal of occupational medicine. : official publication of the Industrial Medical Association. 16 (3): 150–1.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Epidemiologic Notes and Reports Angiosarcoma of the Liver Among Polyvinyl Chloride Workers – Kentucky, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. 1997. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00046136.htm

- ^ National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAP) for Vinyl Chloride Subpart F, OMB Control Number 2060-0071, EPA ICR Number 0186.09 (Federal Register: September 25 2001 (Volume 66, Number 186))

- ^ EPA Toxicologica Review of Vinyl Chloride i Support of Informaiton on the IRIS. May 2000

- ^ Jim Morris, "In Strictest Confidence . The chemical industry's secrets," Houston Chronicle. Part One: "Toxic Secrecy," June 28 1998, pgs. 1A, 24A-27A; Part Two: "High-Level Crime," June 29 1998, pgs. 1,A, 8A, 9A; and Part Three: "Bane on the Bayou," July 26 1998, pgs. 1A, 16A.]

- ^ “ATSDR Study Finds Dioxin Levels in Calcasieu Parish Residents Similar to National Levels,” available at: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/NEWS/calcasieula031506.html; “ATSDR Study Finds Dioxin Levels Among Lafayette Parish Residents Similar to National Levels,” available at: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/NEWS/lafayettela031606.html; ATSDR Report: Serum Dioxin Levels In Residents Of Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana, October 2005, Publication Number PB2006-100561, available from the National Technical Information Services, Springfield, Virginia, phone: 1-800-553-6847/1-703-605-6244

- ^ "Calcasieu Cancer Rates Similar to State/National Averages." News Release, State of Louisiana Dept. of Health and Hospitals. January 17, 2002

- ^ National Renewable Energy Laboratory, "Polyvinyl Chloride Plastics in Municipal Solid Waste Combustion," NREL/TP-430- 5518, Golden CO, April 1993

- ^ Rigo, H.G., Chandler, A. J., and Lanier, W.S., "The Relationship between Chlorine in Waste Streams and Dioxin Emissions from Waste Combustor Stacks," American Society of Mechanical Engineers Report CRTD, Vol 36, New York 1995

- ^ Steiglitz, L., and Vogg, H., "Formation Decomposition of Polychlorodibenzodioxins and Furans in Municipal Waste," Report KFK4379, Laboratorium fur Isotopentechnik, Institut for Heize Chemi, Kerforschungszentrum Karlsruhe, Feb 1988.

- ^ Pat Costner etal, "PVC: A Primary Contributor to the U.S. Dioxin Burden; Comments submitted to the U.S. EPA Dioxin Reassessment," (Washington, D.C. Greenpeace U.S.A., February 1995

- ^ US EPA, The Inventory of Sources and Environmental Releases of Dioxin-Like Compounds in the United States: The Year 2002 Update, May 2007

- ^ US EPA2005

- ^ Costner, Pat, (2005), "Estimating Releases and Prioritizing Sources in the Context of the Stockholm Convention", International POPs Elimination Network, Mexico.

- ^ Costner 2005

- ^ Beychok, M.R., A data base of dioxin and furan emissions from municipal refuse incinerators, Atmospheric Environment, Elsevier B.V., January 1987

- ^ Katami, Takeo, et al. (2002) "Formation of PCDDs, PCDFs, and Coplanar PCBs from Polyvinyl Chloride during Combustion in an Incinerator" Environ. Sci. Technol., 36, 1320-1324. and Wagner, J., Green, A. 1993. Correlation of chlorinated organic compound emissions from incineration with chlorinated organic input. Chemosphere 26 (11): 2039-2054. and Thornton, Joe (2002) "Environmental Impacts of polyvinyl Chloride Building Materials", Healthy Building Network, Washington, DC.

- ^ The USGBC document can be found on line at https://www.usgbc.org/ShowFile.aspx?DocumentID=2372 An analysis by the Healthy Building NEtwork is at http://www.pharosproject.net/wiki/index.php?title=USGBC_TSAC_PVC

- ^ AB 2505 Californians Against Waste http://www.cawrecycles.org/issues/current_legislation/ab2505_08

- ^ http://info.sen.ca.gov/pub/07-08/bill/asm/ab_2501-2550/ab_2505_cfa_20080415_092217_asm_comm.html

- ^ http://www.pvcinfo.be/bestanden/Progress%20report%202002_fr.pdf, Page 11, "Mise A Jour Du Projet, Projet Ferrari - Texiloop®

Movies

- Blue Vinyl (2002). Directed by Daniel B. Gold and Judith Helfand. Learn more about it at [2]

- Sam Suds and the Case of PVC, the Poison Plastic (2006). Watch it at [3]

- An Overview of the Benefits of Vinyl (2006) by Dr. Patrick Moore, founding member of Greenpeace and former Director of Greenpeace International. See it at [4]

External links

- PharosWiki entry on PVC - more detailed referenced information on health issues associated with PVC life cycle.

- PVC Information "Vinyl is all around us, but no other plastic poses such direct environmental and human health risks."

- The Association between Asthma and Allergic Symptoms in Children and Phthalates in House Dust: A Nested Case-Control Study

- Polyvinyl Chloride - General Info "PVC – Toxic Plastic"

- The European PVC Portal (European Council of Vinyl Manufacturers)

- European Council of Plasticisers and Intermediates

- Uni-Bell PVC Pipe Association

- An introduction to vinyl

- The Vinyl Council of Canada