Lagrange point

The Lagrangian points (/ləˈgrɑːnʒiən/; also Lagrange point, L-point, or libration point), are the five positions in an orbital configuration where a small object affected only by gravity can theoretically be stationary relative to two larger objects (such as a satellite with respect to the Earth and Moon). The Lagrange points mark positions where the combined gravitational pull of the two large masses provides precisely the centripetal force required to rotate with them. They are analogous to geostationary orbits in that they allow an object to be in a "fixed" position in space rather than an orbit in which its relative position changes continuously.

A more precise but technical definition is that the Lagrangian points are the stationary solutions of the circular restricted three-body problem.[1] For example, given two massive bodies in circular orbits around their common center of mass, there are five positions in space where a third body, of comparatively negligible mass, could be placed which would then maintain its position relative to the two massive bodies. As seen in a rotating reference frame with the same period as the two co-orbiting bodies, the gravitational fields of two massive bodies combined with the centrifugal force are in balance at the Lagrangian points, allowing the third body to be stationary with respect to the first two bodies.[2]

History and concepts

The three collinear Lagrange points were first discovered by Euler around 1750.[3]

In 1772, the Italian-French mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange was working on the famous three-body problem when he discovered an interesting quirk in the results. Originally, he had set out to discover a way to easily calculate the gravitational interaction between arbitrary numbers of bodies in a system, because Newtonian mechanics conclude that such a system results in the bodies orbiting chaotically until there is a collision, or a body is thrown out of the system so that equilibrium can be achieved. The logic behind this conclusion is that a system with one body is trivial, as it is merely static relative to itself; a system with two bodies is very simple to solve for, as the bodies orbit around their common center of mass. However, once more than two bodies are introduced, the mathematical calculations become very complicated. A situation arises where you would have to calculate every gravitational interaction between every pair of objects at every point along its trajectory.

Lagrange, however, wanted to make this simpler. He did so with a simple hypothesis: The trajectory of an object is determined by finding a path that minimizes the action over time. This is found by subtracting the potential energy from the kinetic energy. With this way of thinking, Lagrange re-formulated the classical Newtonian mechanics to give rise to Lagrangian mechanics. With his new system of calculations, Lagrange’s work led him to hypothesize how a third body of negligible mass would orbit around two larger bodies which were already in a near-circular orbit. In a frame of reference that rotates with the larger bodies, he found five specific fixed points where the third body experiences zero net force as it follows the circular orbit of its host bodies (planets).[4] These points were named “Lagrangian points” in Lagrange's honor. It took over a hundred years before his mathematical theory was observed with the discovery of the Trojan asteroids in the 1900s at the Lagrange points of the Sun–Jupiter system.

In the more general case of elliptical orbits, there are no longer stationary points in the same sense: it becomes more of a Lagrangian “area”. The Lagrangian points constructed at each point in time, as in the circular case, form stationary elliptical orbits which are similar to the orbits of the massive bodies. This is due to Newton's second law (), where p = mv (p the momentum, m the mass, and v the velocity) is invariant if force and position are scaled by the same factor. A body at a Lagrangian point orbits with the same period as the two massive bodies in the circular case, implying that it has the same ratio of gravitational force to radial distance as they do. This fact is independent of the circularity of the orbits, and it implies that the elliptical orbits traced by the Lagrangian points are solutions of the equation of motion of the third body.

The Lagrangian points

The five Lagrangian points are labeled and defined as follows:

L1

The L1 point lies on the line defined by the two large masses M1 and M2, and between them. It is the most intuitively understood of the Lagrangian points: the one where the gravitational attraction of M2 partially cancels M1 gravitational attraction.

- Example: An object which orbits the Sun more closely than the Earth would normally have a shorter orbital period than the Earth, but that ignores the effect of the Earth's own gravitational pull. If the object is directly between the Earth and the Sun, then the effect of the Earth's gravity is to weaken the force pulling the object towards the Sun, and therefore increase the orbital period of the object. The closer to Earth the object is, the greater this effect is. At the L1 point, the orbital period of the object becomes exactly equal to the Earth's orbital period.

The Sun–Earth L1 is ideal for making observations of the Sun. Objects here are never shadowed by the Earth or the Moon. The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) is stationed in a Halo orbit at L1, and the Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) is in a Lissajous orbit, also at the L1 point. The Earth–Moon L1 allows easy access to lunar and earth orbits with minimal change in velocity and would be ideal for a half-way manned space station intended to help transport cargo and personnel to the Moon and back.

L2

The L2 point lies on the line defined by the two large masses, beyond the smaller of the two. Here, the gravitational forces of the two large masses balance the centrifugal force on the smaller mass.

- Example: On the side of the Earth away from the Sun, the orbital period of an object would normally be greater than that of the Earth. The extra pull of the Earth's gravity decreases the orbital period of the object, and at the L2 point that orbital period becomes equal to the Earth's.

The Sun–Earth L2 is a good spot for space-based observatories. Because an object around L2 will maintain the same orientation with respect to the Sun and Earth, shielding and calibration are much simpler. The Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe is already in orbit around the Sun–Earth L2. The future Planck satellite, Herschel Space Observatory, Gaia probe, and James Webb Space Telescope will be placed at the Sun–Earth L2. Earth–Moon L2 would be a good location for a communications satellite covering the Moon's far side.

If the mass of the smaller object (M2) is much smaller than the mass of the larger object (M1) then L1 and L2 are at approximately equal distances r from the smaller object, equal to the radius of the Hill sphere, given by:

where R is the distance between the two bodies.

This distance can be described as being such that the orbital period, corresponding to a circular orbit with this distance as radius around M2 in the absence of M1, is that of M2 around M1, divided by .

Examples:

L3

The L3 point lies on the line defined by the two large masses, beyond the larger of the two.

- Example: L3 in the Sun–Earth system exists on the opposite side of the Sun, a little outside the Earth's orbit but slightly closer to the Sun than the Earth is. (This apparent contradiction is because the Sun is also affected by the Earth's gravity, and so orbits around the two bodies' barycentre, which is however well inside the body of the Sun.) At the L3 point, the combined pull of the Earth and Sun again causes the object to orbit with the same period as the Earth.

The Sun–Earth L3 point was a popular place to put a "Counter-Earth" in pulp science fiction and comic books — though of course, once space based observation was possible via satellites and probes, it was shown to hold no such object. Actually, the Sun–Earth L3 is highly unstable, because the gravitational forces of the other planets outweigh that of the Earth (Venus, for example, comes within 0.3 AU of L3 every 20 months).

L4 and L5

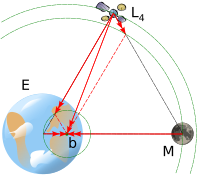

The L4 and L5 points lie at the third corners of the two equilateral triangles in the plane of orbit whose common base is the line between the centres of the two masses, such that the point lies behind (L5) or ahead of (L4) the smaller mass with regard to its orbit around the larger mass.

The reason these points are in balance is that, at L4 and L5, the distances to the two masses are equal. Accordingly, the gravitational forces from the two massive bodies are in the same ratio as the masses of the two bodies, and so the resultant force acts through the barycentre of the system; additionally, the geometry of the triangle ensures that the resultant acceleration is to the distance from the barycentre in the same ratio as for the two massive bodies. The barycentre being both the centre of mass and centre of rotation of the system, this resultant force is exactly that required to keep a body at the Lagrange point in orbital equilibrium with the rest of the system. (Indeed, the third body need not have negligible mass; the general triangular configuration was discovered by Lagrange in work on the 3-body problem.)

L4 and L5 are sometimes called triangular Lagrange points or Trojan points. The name Trojan points comes from the Trojan asteroids at the Sun–Jupiter L4 and L5 points, which themselves are named after characters from Homer's Iliad (the legendary siege of Troy). Asteroids at the L4 point, which leads Jupiter, are referred to as the 'Greek camp', while at the L5 point they are referred to as the 'Trojan camp'. These asteroids are (largely) named after characters from the respective sides of the Trojan War.

- Examples:

- The Sun–Earth L4 and L5 points lie 60° ahead of and 60° behind the Earth as it orbits the Sun. They contain interplanetary dust.

- The Earth–Moon L4 and L5 points lie 60° ahead of and 60° behind the Moon as it orbits the Earth. They may contain interplanetary dust in what is called Kordylewski clouds.

- The Sun–Jupiter L4 and L5 points are occupied by the Trojan asteroids.

- Neptune has Trojan Kuiper Belt Objects at its L4 and L5 points.

- Saturn's moon Tethys has two much smaller satellites at its L4 and L5 points named Telesto and Calypso, respectively.

- Saturn's moon Dione has smaller moons Helene and Polydeuces at its L4 and L5 points, respectively.

- The giant impact hypothesis suggests that an object named Theia formed at L4 or L5 and crashed into the Earth after its orbit destabilized, forming the moon.

Stability

The first three Lagrangian points are technically stable only in the plane perpendicular to the line between the two bodies. This can be seen most easily by considering the L1 point. A test mass displaced perpendicularly from the central line would feel a force pulling it back towards the equilibrium point. This is because the lateral components of the two masses' gravity would add to produce this force, whereas the components along the axis between them would balance out. However, if an object located at the L1 point drifted closer to one of the masses, the gravitational attraction it felt from that mass would be greater, and it would be pulled closer. (The pattern is very similar to that of tidal forces.)

Although the L1, L2, and L3 points are nominally unstable, it turns out that it is possible to find stable periodic orbits around these points, at least in the restricted three-body problem. These perfectly periodic orbits, referred to as "halo" orbits, do not exist in a full n-body dynamical system such as the solar system. However, quasi-periodic (i.e. bounded but not precisely repeating) orbits following Lissajous curve trajectories do exist in the n-body system. These quasi-periodic Lissajous orbits are what all Lagrangian point missions to date have used. Although they are not perfectly stable, a relatively modest effort at station keeping can allow a spacecraft to stay in a desired Lissajous orbit for an extended period of time. It also turns out that, at least in the case of Sun–Earth L1 missions, it is actually preferable to place the spacecraft in a large amplitude (100,000–200,000 km) Lissajous orbit, instead of having it sit at the Lagrangian point, because this keeps the spacecraft off the direct Sun–Earth line, thereby reducing the impact of solar interference on the Earth–spacecraft communications links. Another interesting and useful property of the collinear Lagrangian points and their associated Lissajous orbits is that they serve as "gateways" to control the chaotic trajectories of the Interplanetary Transport Network.

In contrast to the collinear Lagrangian points, the triangular points (L4 and L5) are stable equilibria (cf. attractor), provided that the ratio of M1/M2 is greater than 24.96.[5][6] This is the case for the Sun–Earth and, by a smaller margin, the Earth–Moon systems. When a body at these points is perturbed, it moves away from the point, but the Coriolis effect bends the object's path into a stable, kidney bean‐shaped orbit around the point (as seen in the rotating frame of reference). However, in the Earth–Moon case, the problem of stability is greatly complicated by the appreciable solar gravitational influence.[7]

Intuitive explanation

This section non-mathematically (intuitively[8]) explains the five Lagrangian points using the Earth–Moon system.

Lagrangian points L2 through L5 only exist in rotating systems, as in the monthly orbiting of the Moon about the Earth. At these points, an outward (fictitious, as explained below) centrifugal force is balanced by the attractive gravitational forces of the Moon and Earth.

Imagine a person using their hand to spin a stone at the end of a string. The string provides a tension force that continuously accelerates the stone towards the center. To an ant standing on the stone, however, it seems as if there is a force trying to fling him directly outward from the center. This apparent or fictitious force is called the centrifugal force . This same effect is present in the Earth–Moon system, where the role of the string is played by the summed (or net) effect of the two attractive gravities, and the stone is an asteroid or a spacecraft. The Earth–Moon system rotates about its combined center of mass, or barycenter. Because the Earth is much heavier than the Moon, this point is located within the Earth (about a thousand miles below the surface) Any object gravitationally held by the rotating Earth–Moon system will sense a centrifugal force directed away from the barycenter, in the same way as does the ant on the stone.

Unlike the other Lagrangian points, L1 would exist even in a non-rotating (static or inertial) system. Rotation slightly pushes L1 away from the (heavier) Earth towards the (lighter) Moon. L1 is slightly unstable (see stability above) because drifting towards the Moon or Earth increases one gravitational attraction while decreasing the other, causing more drift.

At Lagrangian points L2, L3, L4, and L5, a satellite feels an outward centrifugal force, away from the barycenter, that exactly balances the attractive gravity of the Earth and Moon. L2 and L3 are slightly unstable because small changes in satellite position more strongly affect gravity than the balancing centrifugal force. Stability at L4 and L5 depends crucially on the satellite being pulled in three different directions, namely the outward centrifugal force away from the barycenter, balancing the inward gravitational forces towards the Moon and Earth.

Lagrangian point missions

The Lagrangian point orbits have unique characteristics that have made them a good choice for performing some kinds of missions. These missions generally orbit the points rather than occupy them directly.

| Mission | Lagrangian point | Agency | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) | Sun-Earth L1 | NASA | Operational |

| Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) | Sun-Earth L1 | NASA | Operational |

| WIND | Sun-Earth L1 | NASA | Operational |

| Genesis | Sun-Earth L1 | NASA | Mission ended, left L1 point |

| International Sun/Earth Explorer 3 (ISEE-3) | Sun-Earth L1 | NASA | Original mission ended, left L1 point |

| Deep Space Climate Observatory | Sun-Earth L1 | NASA | On hold |

| Solar-C | Sun-Earth L1 | Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency | Possible mission after 2010 |

| Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) | Sun-Earth L2 | NASA | Operational |

| Planck satellite | Sun-Earth L2 | ESA | Scheduled to launch in Spring 2009 |

| Herschel Space Observatory | Sun-Earth L2 | ESA | Schedule to launch in Spring 2009 (with Planck satellite) |

| James Webb Space Telescope | Sun-Earth L2 | NASA, ESA, Canadian Space Agency | Scheduled to launch in June 2013 or later |

| SMART-1 | Moon-Earth L1 (flyby) | ESA | Mission ended, deliberately crashed into moon |

| Communication satellite covering the far side of the Moon | Earth–Moon L2 | NASA | Proposed in 1968[9] |

| Space colonization and manufacturing | Earth-Moon L4 or L5 | L5 Society | Proposed in 1974 |

| Solar shade | Sun-Earth L1 | - | Various proposals |

| New Horizons | Sun-Neptune L5 (flyby) | NASA | Launched; scheduled to arrive August 1, 2014 |

Natural examples

In the Sun–Jupiter system several thousand asteroids, collectively referred to as Trojan asteroids, are in orbits around the Sun–Jupiter L4 and L5 points. Recent observations suggest that the Sun–Neptune L4 and L5 points, known as the Neptune Trojans, may be very thickly populated, containing large bodies an order of magnitude more numerous than the Jupiter Trojans. Other bodies can be found in the Sun–Mars and Saturn–Saturnian satellite systems. There are no known large bodies in the Sun–Earth system's Trojan points, but clouds of dust surrounding the L4 and L5 points were discovered in the 1950s. Clouds of dust, called Kordylewski clouds, even fainter than the notoriously weak gegenschein, may also be present in the L4 and L5 of the Earth–Moon system.

The Saturnian moon Tethys has two smaller moons in its L4 and L5 points, Telesto and Calypso. The Saturnian moon Dione also has two Lagrangian co-orbitals, Helene at its L4 point and Polydeuces at L5. The moons wander azimuthally about the Lagrangian points, with Polydeuces describing the largest deviations, moving up to 32 degrees away from the Saturn–Dione L5 point. Tethys and Dione are hundreds of times more massive than their "escorts" (see the moons' articles for exact diameter figures; masses are not known in several cases), and Saturn is far more massive still, which makes the overall system stable.

Other co-orbitals

The Earth's companion object 3753 Cruithne is in a relationship with the Earth which is somewhat Trojan-like, but different from a true Trojan. This asteroid occupies one of two regular solar orbits, one of them slightly smaller and faster than the Earth's orbit, and the other slightly larger and slower. The asteroid periodically alternates between these two orbits due to close encounters with Earth. When the asteroid is in the smaller, faster orbit and approaches the Earth, it gains orbital energy from the Earth and moves up into the larger, slower orbit. It then falls farther and farther behind the Earth, and eventually Earth approaches it from the other direction. Then the asteroid gives up orbital energy to the Earth, and drops back into the smaller orbit, thus beginning the cycle anew. The cycle has no noticeable impact on the length of the year, because Earth's mass is over 20 billion (2 × 1010) times more than 3753 Cruithne.

Epimetheus and Janus, satellites of Saturn, have a similar relationship, though they are of similar masses and so actually exchange orbits with each other periodically. (Janus is roughly 4 times more massive but still light enough for its orbit to be altered.) Another similar configuration is known as orbital resonance, in which orbiting bodies tend to have periods of a simple integer ratio, due to their interaction.

In fiction

Lagrange points are mentioned in science fiction from time to time (most often hard science fiction), but, due to the general lack of public familiarity with them, they are rarely used as a plot device or reference

L1

- In Arthur Clarke's novel A Fall of Moondust, the station Lagrange II is situated at L1, and contributes vitally to locating Selene.

- In Arthur Clarke and Stephen Baxter's novel Sunstorm, the L1 point plays a crucial role in the building of a shield that has the purpose of saving Earth from a storm of energy from the Sun.

- In the Xbox video game Halo: Combat Evolved (2001) and sequel Halo 2 (2004), Halo Megastructures play key locations throughout the games. In Halo: CE and Halo 2, the Halo structures are in L1 Lagrange points between the Gas Giants (and a moon) Threshold and Substance, respectively.

- In the Hugo Award-winning novel A Deepness in the Sky by Vernor Vinge, a temporary human habitat is built at the L1 point between the planet Arachna and its primary star, a highly variable dwarf called the On/Off Star.

- The planet on which Pitch Black is set receives continual daylight: an orrery depicts it at the apparent L1 point between one star and a pair of tightly orbiting stars, receiving periodic eclipses from a pair of gas giants occupying a wider orbit about L1 in the same plane.

- In Peter F Hamilton's Night's Dawn Trilogy, a ZTT jump drive cannot be used in a strong gravitational field. In the first book of the trilogy, The Reality Dysfunction, the main characters cannot escape from a gas giant's gravity well before their pursuers catch up with them. Instead, they race to the Lagrange point between the gas giant and one of its moons in order to activate their drive. Successful execution of this untried and reckless maneuver gains captain Joshua Calvert the nickname "LaGrange" Calvert. In the second book The Neutronium Alchemist, a visit is paid to the supposed home planet of the Kiint, Jobis, which features three moons orbiting the Lagrange One point, rotating around a common centre.

L2

- See also: Lilith (hypothetical moon)

- In the TV series Quatermass II, the hostile aliens live on a small asteroid "no more than half a mile across" at a "theoretical point of equilibrium" on the dark side of the Earth, although neither L2 nor Lagrange are mentioned by name (the term "Bieber Variation" is used instead).

- In the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode, "The Survivors", the Enterprise is surprised by an enemy ship that had been hiding in a Lagrange point.

- In the manga series Battle Angel Alita: Last Order, the ex-colony ship turned space station Leviathan 1 is at the L2 point in the Earth/Moon system.

- In John Varley's book Wizard, a religious group called the Coven set up a habitat at L2 to make themselves as remote as possible from the earth. L2 later slowly deteriorates into the space version of an unorganized shantytown as anyone with enough cash can set up a home there. "L2 became known as Sargasso Point to the pilots who carefully avoided it; those who had to travel through it called it the Pinball Machine, and they didn't smile."

L3

- See also: Counter-Earth

- In the third season of the TV series Lexx, the planets Fire and Water are found to reside in Earth's L3 point.

- John Norman's Gor series takes place on a counter earth.

- In Mobile Suit Gundam 00, Celestial Being have established a base at Lagrange-3. Here, they can make repairs as well as introduce new units.

L4

- In Larry Niven's novels The Integral Trees and The Smoke Ring, the L4 and L5 points of the Smoke Ring (a ring of breathable air and plant life orbiting a neutron star) have become gathering places for masses of water, living things, and human settlers.

- The eponymous interplanetary relay station in George O. Smith's "Venus Equilateral" stories was located in the L4 point of the Sun–Venus system.

- In the Xbox 360 game Mass Effect a group of inhabited space stations are situated at the L4 and L5 points.

- In John C. McLoughlin's novel 'The Helix and the Sword' L4 is the location of a key space station rumored to be inhabited by Ogres and Trolls who serve the Apolcalyptic Horseman of Pestilence.

- In Robert L. Forward's novel 'Rocheworld' the double planet system made up of Eau Lobe and Roche Lobe has an L4 point, the middle of which contains an interplanetary waterfall 80 km high.

L5

- The L5 Lagrange point is mentioned in L5: First City in Space, an early IMAX 3D movie.

- In William Gibson's novel Neuromancer, much of the action takes place in the L5 "archipelago", the location of many space stations.

- The planet Troas in the stories "Sucker Bait" by Isaac Asimov and "Question and Answer" by Poul Anderson was located in the L5 point of a fictional binary star system.

- The space station Babylon 5 is described to be located "at the L-5 point in a binary star system between a moon and a barren, lifeless planet."[10]

- In his book "The High Frontier" Dr. Gerard O'Neill proposed the establishment of gigantic Space Islands in L5. The inhabitants of the L5 Society should convert Lunar material to huge solar power satellites.

- In Hideo Kojima's video game Policenauts, the setting of the game, an O'Neill model space colony, is located at the L5 Lagrange point.

- In Dan Simmons's novel The Rise of Endymion, the headquarters of the Pax Mercantilus is located at the L5 point of the planet Pacem, where CEO Kenzo Isozaki has a splendid view of the planet.

Unspecified Lagrange Points

- The Japanese anime sagas of the Gundam series make wide use of massive space colonies parked in Lagrangian points. The colonization of the Lagrange points depicted in the many Gundam series draws extensively from Gerard O'Neill's book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space. The series Mobile Suit Gundam, Gundam Wing and Gundam SEED in particular are set around conflicts between Earth and forces acting on behalf of its space colonies.

- In the Starfire strategy game and the series of military science-fiction novels based on it, written by David Weber and Steve White, the warp points which allow starships to transit between solar systems without moving at faster-than-light speeds typically form at the Lagrange points.

- Lagrange points are famously mentioned in Arthur C. Clarke's novel 2010: Odyssey Two and the subsequent science fiction film 2010, where the Discovery spacecraft is located on a Lagrange point. The movie expands on this, claiming that Discovery is located at a point between Io and Jupiter, which would place it in the L1 point of the Jupiter–Io system.

- Lagrange points also play a role in the Larry Niven/Jerry Pournelle classic The Mote in God's Eye.

- In Robert Forward's Rocheworld, the locations for Lagrange points around a binary planet are discussed in contrast to typical system.

- In Iain M. Banks' The Algebraist, Lagrange points and their alternate forms are central to the plot as possible locations for wormholes.

- In the Independence War computer games, Lagrange points L4 and L5 are used as the only locations for jump-points.

- In the Battletech game series, a star's Nadir and Zenith are the standard hyperspace jump points for most interstellar spacecraft. Lagrange points (only the L1 point) are sometimes used to enter a system closer to planets, almost always for small-scale military or pirate operations due to the risk of catastrophic misjumps.

- In the Halo novels, the Lagrange points are the only places where a human ship can safely make a slipspace jump.

- In the PC video game Star Wars: X-Wing, Lagrange points are mentioned in the briefings of some missions that revolve around attacking objects placed at them.

- In the Robert A. Heinlein novel The Number of the Beast, two of the main characters engage in a discussion of adding planets to the solar system at Lagrange points.

- In the sci-fi series Stargate Atlantis, there was a defensive satellite located at a Lagrangian point in the solar system in which Atlantis was located.[11]

- In 1991, Konami released a science fiction RPG for the NES in Japan called Lagrange Point.

- In the Robotech television series, an effect called an Orbital Warp Blast is created when a spaceship creates "a phenomenon known as the molecular vacuum" at a fictional "Lagrange Point 6, approximately 20,000 kilometers from Mars" (where one does not exist in the real world).

- In The Monkeys Thought 'Twas All In Fun by Orson Scott Card, a structure called the Trojan Object appears at L4 or L5.

- In the Star Trek novel The Abode of Life by Lee Correy, Captain Kirk states the planet Mercan has no Lagrangian points.

- In a parody of the science fiction comic Freefall, a character refers to a satellite bar located in "the Lagrange point" so that it's always Happy hour there. He then heads for the bar promising to be back before sunset (which never happens).

- In the Ken MacLeod novel The Star Fraction, reference is made to a collection of human habitats located at the Earth-Sun Lagrange point, with semi-permanent residents. Implicitly, it is the L1 point which is referred to.

See also

- Euler's three-body problem

- List of objects at Lagrangian points

- Lunar space elevator

- Home on Lagrange (The L5 Song)

- L5 Society

- Horseshoe orbit

- Hill sphere

Notes and references

- ^ "Restricted Three-Body Problem", Science World.

- ^ "Lagrange Points" by Enrique Zeleny, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- ^ Koon, W. S. (2006). Dynamical Systems, the Three-Body Problem, and Space Mission Design. p. 9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:Fr icon Lagrange, Joseph-Louis (1867–1892). "Tome 6, Chapitre II: Essai sur le problème des trois corps". Oeuvres de Lagrange. Gauthier-Villars. pp. 272–292.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Actually

- ^ The Lagrange Points – Neil J. Cornish with input from Jeremy Goodman

- ^ "A Search for Natural or Artificial Objects Located at the Earth-Moon Libration Points". Icarus.

- ^ Tyson, Neil deGrasse, Death by Black Hole, ©2007, ISBN 9780393062243

- ^ P. E. Schmid (June 1968). "Lunar Far-Side Communication Satellites" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ^ Compiled by Lee Whiteside (Updated 11/4/92). "Babylon 5 General Information". Retrieved 2008-07-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Siege", Stargate Atlantis.

Further reading

- Lagrange, J.-L. Essai sur le problème des trois corps, 1772. Prix de l'Académie Royale des Sciences de Paris, tome IX, in vol. 6 of Oeuvres de Lagrange (Gauthier-Villars, Paris, 1873), 272–282.

External links

- Explanation of Lagrange points – Prof. Neil J. Cornish

- A NASA explanation – also attributed to Neil J. Cornish

- Explanation of Lagrange points – Prof. John Baez

- Geometry and calculations of Lagrange points – Dr J R Stockton

- Locations of Lagrange points, with approximations – Dr. David Peter Stern

- An online calculator to compute the precise positions of the 5 Lagrange points for any 2-body system – Tony Dunn

![{\displaystyle r\approx R{\sqrt[{3}]{\frac {M_{2}}{3M_{1}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1175643479ba922598c78a6d4dfcf7fff160bfe7)