User:AlotToLearn

THIS IS MY USER PAGE

IT CONTAINS MATERIAL THAT I AM REVIEWING

PLEASE DO NOT EDIT IT

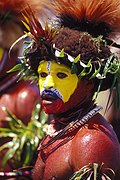

Culture (from the Latin cultura stemming from colere, meaning "to cultivate")[1] is difficult to define — in 1952, Alfred Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn compiled a list of 164 definitions of "culture" in Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions.[2] — but most commonly means an excellence of taste in the fine arts and humanities; an integrated pattern of human knowledge, belief, and behavior that depends upon the capacity for symbolic thought and social learning; or the set of shared attitudes, values, goals, and practices that characterizes an institution, organization or group. When the concept first emerged in eighteenth and nineteenth century Europe, it connoted a process of cultivation or improvement, as in agriculture or horticulture. In the nineteenth century it came to refer first to the betterment or refinement of the individual, especially through education, and then to the fulfillment of national aspirations or ideals. In the mid-nineteenth century some scientists began to argue that culture signifies a universal human capacity. In the twentieth century, the concept emerged as central to American anthropology and referred to all non-genetic human phenomena. Specifically, the term was used in two senses: first, to refer to the evolved human capacity to classify and represent experiences symbolically, and to act imaginatively and creatively; second, it referred to distinct ways that people living in different parts of the world classified and represented their experiences, and acted creatively. Following World War II, the term became important, albeit with different meanings, in other disciplines such as sociology, cultural studies, organizational psychology and management studies.

In the nineteenth century, humanists such as English poet and essayist Matthew Arnold (1822-1888) used the word "culture" to refer to an ideal of individual human refinement, of "the best that has been thought and said in the world."[3]

- "...culture being a pursuit of our total perfection by means of getting to know, on all the matters which most concern us, the best which has been thought and said in the world."[3]

culture referred to an élite ideal and was associated with such activities as art, classical music, and haute cuisine.[4]

"culture" was identified with "civilization" (from lat. civitas, city).

distinction .... between "high culture", namely the culture of the ruling social group and "low culture."

In other words, the idea of "culture" that developed in Europe during the 18th and early 19th centuries reflected inequalities within European societies.[5]

Matthew Arnold contrasted "culture" with "anarchy;" other Europeans, following philosophers Thomas Hobbes Jean-Jacques Rousseau, contrasted "culture" with "the state of nature." According to Hobbes and Rousseau, the Native Americans who were being conquered by Europeans from the 16th centuries on were living in a state of nature.

in the 19th century this opposition was also expressed through the contras between "civilized" and "uncivilized." According to this way of thinking, one can classify some countries and nations as more civilized than others, and some people as more cultured than others. This contrast led to Herbert Spencer's theory of Social Darwinism and Lewis Henry Morgan's theory of cultural evolution.

In 1870 Edward Tylor (1832-1917) applied these ideas of higher versus lower culture to propose a theory of the evolution of religion. According to this theory, religion evolves from more polytheistic to more monotheistic forms.[6]

Herder proposed a collective form of bildung: "For Herder, Bildung was the totality of experiences that provide a coherent identity, and sense of common destiny, to a people."[7]

In 1795 the great linguist and philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767-1835) called for an anthropology that would synthesize Kant's and Herder's interests.

During the Romantic era, scholars in Germany developed a more inclusive notion of culture as "worldview." According to this school of thought, each ethnic group has a distinct worldview that is incommensurable with the worldviews of other groups.

In 1860, Adolf Bastian (1826-1905) argued for "the psychic unity of mankind". He proposed that a scientific comparison of all human societies would reveal that distinct worldviews consisted of the same basic elements. According to Bastian, all human societies share a set of "elementary ideas" (Elementargedanken); different cultures, or different "folk ideas" (Volkergedanken), are local modifications of the elementary ideas.[8] This view paved the way for the modern understanding of culture. Franz Boas (1858-1942) was trained in this tradition, and he brought it with him when he left Germany for the United States.

Anthropology

In American anthropology, "culture" most commonly refers to the universal human capacity to classify and encode their experiences symbolically, and communicate symbolically encoded experiences socially.

Biological Anthropology: the Evolution of Culture

Discussion concerning culture among biological anthropologists centers around two debates. First, is culture uniquely human, or shared by other species (most notably, other primates)? Second, how did human culture evolve among human beings?

The question of whether culture should be defined as any or all learned behavior remains. Physical anthropologists who focus on human evolution are concerned with how human beings evolved to be different from other species. The mainstream view among these researchers is that a more precise definition of culture, and one that is exclusively human, is necessary.

Linguistics

Cultural Anthropology

1899-1946: Universal versus Particular

in the 19th century with German anthropologist Adolf Bastian's theory of the "psychic unity of mankind," which challenged the identification of "culture" with the way of life of European elites

Tylor in 1874 described culture in the following way: "Culture or civilization, taken in its wide ethnographic sense, is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society."[9]

Alfred Kroeber (1876-1970) identified culture with the "superorganic," that is, a domain with ordering principles and laws that could not be explained by or reduced to biology.[10]

In 1973 Gerald Weiss proposed as the most scientifically useful definition that "culture" be defined "as our generic term for all human nongenetic, or metabiological, phenomena" (italics in the original).[11]

At the time the dominant model of culture was that of cultural evolution, which posited that human societies progressed through stages of savagery to barbarism to civilization; thus, societies that for example are based on horticulture and Iroquois kinship terminology are less evolved that societies based on agriculture and Eskimo kinship terminology.

Boas established the principle of cultural relativism and trained students to conduct rigorous participant observation field research in different societies.

Boas argued that cultural "types" or "forms" are always in a state of flux.[12][13]

His student Alfred Kroeber argued that the "unlimited receptivity and assimilativeness of culture" made it practically impossible to think of cultures as discrete things.[14].

Boas's students dominated cultural anthropology through World War II, and continued to have great influence through the 1960s. They were especially interested in two phenomena: the great variety of forms culture took around the world,[15] and the many ways individuals were shaped by and acted creatively through their own cultures.[16][17] This led his students to focus on the history of cultural traits — how they spread from one society to another, and how their meanings changed over time[18][19] — and the life histories of members of other societies.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27]

Others, such as Ruth Benedict (1887-1948) and Margaret Mead (1901-1978), produced monographs or comparative studies analyzing the forms of creativity possible to individuals within specific cultural configurations.[28][29][30]

Since Boas, anthropologists have argued as to whether "culture" can be thought of as a bounded and integrated thing, or as a quality of a diverse collection of things, the numbers and meanings of which are in constant flux. Benedict suggested that in any given society cultural traits may be more or less "integrated," that is, constituting a pattern of action and thought that gives purpose to people’s lives, and provides them with a basis from which to evaluate new actions and thoughts, although she implies that there are various degrees of integration; indeed, she observes that some cultures fail to integrate. [31] Boas, however, argued that complete integration is rare and that a given culture only appears to be integrated because of observer bias.[32] For Boas, the appearance of such patterns — a national culture, for example — was the effect of a particular point of view.[33]

The second debate has been over the ability to make universal claims about culture. Although Boas argued that anthropologists had yet to collect enough solid evidence from a diverse sample of societies to make any valid general or universal claims about culture, by the 1940s some felt ready. Opposing Boas and his students, Yale anthropologist George Murdock, who compiled the Human Relations Area Files. These files code cultural variables found in different societies, so that anthropologists can use statistical methods to study correlations among different variables.[34][35][36] The ultimate aim of this project is to develop generalizations that apply to increasingly larger numbers of individual cultures. Later, Murdock and Douglas R. White developed the standard cross-cultural sample as a way to refine this method.

Perhaps the most notable attempt to resolve this tension is structuralist anthropology. This approach was developed by Claude Lévi-Strauss, who brought together ideas of Boas (including, through Boas, Bastian's belief in the psychic unity of humankind) and French sociologist's Émile Durkheim's focus on social structures (institutionalized relationships among persons and groups of persons). Instead of making generalizations that applied to large numbers of societies, Lévi-Strauss sought to derive from concrete cases increasingly abstract models of human nature. His method begins with the supposition that culture exists in two different forms: the many distinct structures that could be inferred from observing members of the same society interact (and of which members of a society are themselves aware), and abstract structures developed by analyzing shared ways (such as myths and rituals) members of a society represent their social life (and of which members of a society are not only not consciously aware, but which typically stand in opposition to, or negate, the social structures of which people are aware). He then sought to develop one universal mental structure that could only be inferred through the systematic comparison of particular social and cultural structures. He argued that just as there are laws through which a finite and relatively small number of chemical elements could be combined to create a seemingly infinite variety of things, there were a finite and relatively small number of cultural elements which people combine to create the great variety of cultures anthropologists observe. The systematic comparison of societies would enable an anthropologist to develop this cultural "table of elements," and once completed, this table of cultural elements would enable an anthropologist to analyze specific cultures and achieve insights hidden to the very people who produced and lived through these cultures.[37][38] Structuralism came to dominate French anthropology and, in the late 1960s and 1970s, came to have great influence on American and British anthropology.

Culture and Functionalism

According to Malinowski's theory of functionalism, all human beings have certain biological needs, such as the need for food and shelter, and humankind has the biological need to reproduce. Every society develops its own institutions, which function to fulfill these needs. In order for these institutions to function, individuals take on particular social roles that regulate how they act and interact. Although members of any given society may not understand the ultimate functions of their roles and institutions, an ethnographer can develop a model of these functions through the careful observation of social life.[39]

Culture and social functionism

Radcliffe-Brown rejected Malinowski's notion of function, and believed that a general theory of primitive social life could only be built up through the careful comparison of different societies. Influenced by the work of French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1858-1917), who argued that primitive and modern societies are distinguished by distinct social structures, Radcliffe-Brown argued that anthropologists first had to map out the social structure of any given society before comparing the structures of different societies.[40]

Structural functionalism drew its inspiration primarily from the ideas of Emile Durkheim and Max Weber. Functionalism emphasizes the central role that agreement (consensus) between members of a society on morals plays in maintaining social order. This moral consensus creates an equilibrium, the normal state of society. Durkheim was concerned with the question of how societies maintain internal stability and survive over time. Durkheim proposed that such societies tend to be segmentary, being composed of equivalent parts that are held together by shared values, common symbols, or, as his nephew Mauss held, systems of exchanges

Talcott Parsons developed a theory of social action which he also called "structural functionalism." Parson's intention was to develop a total theory of social action (why people act as they do), and to develop at Harvard and inter-disciplinary program that would direct research according to this theory. His model explained human action as the result of four systems:

- the "behavioral system" of biological needs

- the "personality system" of an individual's characteristics affecting their functioning in the social world

- the "social system" of patterns of units of social interaction, especially social status and role

- the "cultural system" of norms and values that regulate social action symbolically

According to this theory, the second system was the proper object of study for psychologists; the third system for sociologists, and the fourth system for cultural anthropologists.[41][42]

Whereas the Boasians considered all of these systems to be objects of study by anthropologists, and "personality" and "status and role" to be as much a part of "culture" as "norms and values," Parsons envisioned a much narrower role for anthropology and a much narrower definition of culture.

It was only with the rise of structural functionalism that people came to identify "culture" with "norms and values." Many American anthropologists rejected this view of culture (and by implication, anthropology). In 1980 noted anthropologist Eric Wolf wrote,

- As the social sciences transformed themselves into "behavioral" science, explanations for behavior were no longer traced to culture: behavior was to be understood in terms of psychological encounters, strategies of economic choice, strivings for payoffs in games of power. Culture, once extended to all acts and ideas employed in social life, was now relegated to the margins as "world view" or "values."[43]

Culture and society

The combination of American cultural anthropology theory with British social anthropology methods has led to some confusion between the concepts of "society" and "culture." For most anthropologists, these are distinct concepts. Society refers to a group of people; culture refers to a pan-human capacity and the totality of non-genetic human phenomena. Societies are often clearly bounded; cultural traits are often mobile, and cultural boundaries, such as they are, are typically porous, permeable, and plural.[44] During the 1950s and 1960s anthropologists often worked in places where social and cultural boundaries coincided, thus obscuring the distinction. When disjunctures between these boundaries become highly salient, for example during the period of European de-colonization of Africa in the 1960s and 1970s, or during the post-Bretton Woods realignment of globalization, however, the difference often becomes central to anthropological debates.[45][46][47][48][49]

Culture and symbols

Symbolic anthropology is the study of the social construction and social effects of symbols.[50][51][52][53] It is a diverse set of approaches within cultural anthropology that view culture as a symbolic system that arises primarily from human interpretations of the world. Symbolic anthropology may be contrasted with more empirically oriented approaches in anthropology such as cultural materialism

Victor Turner was an important bridge between American and British symbolic anthropology.[54]

Attention to symbols, the meaning of which depended almost entirely on their historical and social context, appealed to many Boasians. Leslie White asked of cultural things, "What sort of objects are they? Are they physical objects? Mental objects? Both? Metaphors? Symbols? Reifications?" In Science of Culture (1949), he concluded that they are objects "sui generis"; that is, of their own kind. In trying to define that kind, he hit upon a previously unrealized aspect of symbolization, which he called "the symbolate"—an object created by the act of symbolization. He thus defined culture as "symbolates understood in an extra-somatic context."[55]

Culture and adaption=

Leslie White was interested in the cultural history of the human species, which he felt should be studied from an evolutionary perspective. Thus, the task of anthropology is to study "not only how culture evolves, but why as well.... In the case of man ... the power to invent and to discover, the ability to select and use the better of two tools or ways of doing something- these are the factors of cultural evolution."[56] He wrote: "In order to live man, like all other species, must come to terms with the external world.... Man employs his sense organs, nerves, glands, and muscles in adjusting himself to the external world. But in addition to this he has another means of adjustment and control.... This mechanism is culture".[57]

White was interested in documenting how, over time, humankind as a whole has through cultural means discovered more and more ways for capturing and harnessing energy from the environment, in the process transforming culture.

At the same time that White was developing his theory of cultural evolution, Julian Steward was developing his theory of cultural ecology. In 1938 he published Basin-Plateau Aboriginal Socio-Political Groups in which he argued that diverse societies — for example the indigenous Shoshone or White farmers on the Great Plains — were not less or more evolved; rather, they had adapted differently to different environments.[58]

Whereas Leslie White was interested in culture understood holistically as a property of the human species, Julian Steward was interested in culture as the property of distinct societies. Like White he viewed culture as a means of adapting to the environment, but he criticized Whites "unilineal" (one direction) theory of cultural evolution and instead proposed a model of "multilineal" evolution in which each society has its own cultural history.[59]

Most promoted materialist understandings of culture in opposition to the symbolic approaches of Geertz and Schneider. Harris, Rappaport, and Vayda were especially important for their contributions to cultural materialism and ecological anthropology, both of which argued that "culture" constituted an extra-somatic (or non-biological) means through which human beings could adapt to life in drastically differing physical environments.

The debate between symbolic and materialist approaches to culture dominated American Anthropologists in the 1960s and 1970s. The Vietnam War and the publication of Dell Hymes' Reinventing Anthropology, however, marked a growing dissatisfaction with the then dominant approaches to culture. Hymes argued that fundamental elements of the Boasian project such as holism and an interest in diversity were still worth pursuing: “interest in other peoples and their ways of life, and concern to explain them within a frame of reference that includes ourselves.”[60] Moreover, he argued that cultural anthropologists are singularly well-equipped to lead this study (with an indirect rebuke to sociologists like Parsons who sought to subsume anthropology to their own project):

- In the practice there is a traditional place for openness to phenomena in ways not predefined by theory or design – attentiveness to complex phenomena, to phenomena of interest, perhaps aesthetic, for their own sake, to the sensory as well as intellectual, aspects of the subject. These comparative and practical perspectives, though not unique to formal anthropology, are specially husbanded there, and might well be impaired, if the study of man were to be united under the guidance of others who lose touch with experience in concern for methodology, who forget the ends of social knowledge in elaborating its means, or who are unwittingly or unconcernedly culture-bound..[61]

It is these elements, Hymes argued, that justify a “general study of man,” that is, “anthropology”.[62]

During this time notable anthropologists such as Mintz, Murphy, Sahlins, and Wolf eventually broke away, experimenting with structuralist and Marxist approaches to culture, they continued to promote cultural anthropology against structural functionalism.[63][64][65][66][67]

Archeological Approaches to Culture: Matter and Meaning

In the 19th century archeology was often a supplement to history, and the goal of archeologists was to identify artifacts according to their typology and stratigraphy, thus marking their location in time and space. Franz Boas established that archeology be one of American anthropology's four fields, and debates among archeologists have often paralleled debates among cultural anthropologists. In the 1920s and 1930s, Australian-British archeologist V. Gordon Childe and American archeologist W. C. McKern independently began moving from asking about the date of an artifact, to asking about the people who produced it — when archeologists work alongside historians, historical materials generally help answer these questions, but when historical materials are unavailable, archeologists had to develop new methods. Childe and McKern focused on analyzing the relationships among objects found together; their work established the foundation for a three-tiered model:

- an individual artifact, which has surface, shape, and technological attributes (e.g. an arrowhead)

- a sub-assemblage, consisting of artifacts that are found, and were likely used, together (e.g. an arrowhead, bow and knife)

- an assemblage of subasemblages that together constitute the archeological site (e.g. the arrowhead, bow and knife; a pot and the remains of a hearth; a shelter)

Childe argued that a "constantly recurring assemblage of artifacts" to be an "archeological culture."[68][69] Childe and others viewed "each archeological culture ... the manifestation in material terms of a specific people."[70]

In 1948 Walter Taylor systematized the methods and concepts that archeologists had developed and proposed a general model for the archeological contribution to knoweldge of cultures. He began with the mainstream understanding of culture as the product of human cognitive activity, and the Boasian emphasis on the subjective meanings of objects as dependent on their cultural context. He defined culture as "a mental phenomenon, consisting of the contents of minds, not of material objects or observable behavior."[71] He then devised a three-tiered model linking cultural anthropology to archeology, which he called conjunctive archeology:

- Culture, which is unobservable and nonmaterial

- Behaviors resulting from culture, which are observable and nonmaterial

- Objectifications, such as artifacts and architecture, which are the result of behavior and material

That is, material artifacts were the material residue of culture, but not culture itself.[72] Taylor's point was that the archeological record could contribute to anthropological knowledge, but only if archeologists reconceived their work not just as digging up artifacts and recording their location in time and space, but as inferring from material remains the behaviors through which they were produced and used, and inferring from these behaviors the mental activities of people. Although many archeologists agreed that their research was integral to anthropology, Taylor's program was never fully implemented. One reason was that his three-tier model of inferences required too much fieldwork and laboratory analysis to be practical.[73] Moreover, his view that material remains were not themselves cultural, and in fact twice-removed from culture, in fact left archeology marginal to cultural anthropology.[74]

In 1962 Leslie White's former student Lewis Binford proposed a new model for anthropological archeology, called "the New Archeology" or "Processual Archeology," based on White's definition of culture as "the extra-somatic means of adaptation for the human organism."[75] This definition allowed Binford to establish archeology as a crucial field for the pursuit of the methodology of Julian Steward's cultural ecology:

- The comparative study of cultural systems with variable technologies in a similar environmental range or similar technologies in differing environments is a major methodology of what Steward (1955: 36-42) has called "cultural ecology," and certainly is a valuable means of increasing our understanding of cultural processes. Such a methodology is also useful in elucidating the structural relationships between major cultural sub-systems such as the social and ideological sub-systems.[76]

In other words, Binford proposed an archeology that would be central to the dominant project of cultural anthropologists at the time (culture as non-genetic adaptations to the environment); the "new archeology" was the cultural anthropology (in the form of cultural ecology or ecological anthropology) of the past.

In the 1980s, there was a movement in the United Kingdom and Europe against the view of archeology as a field of anthropology, echoing Radcliffe-Brown's earlier rejection of cultural anthropology.[77] During this same period, then-Cambridge archeologist Ian Hodder developed "post-processual archeology" as an alternative. Like Binford (and unlike Taylor) Hodder views artifacts not as objectifications of culture but as culture itself. Unlike Binford, however, Hodder does not view culture as an environmental adaptation. Instead, he "is committed to a fluid semiotic version of the traditional culture concept in which material items, artifacts, are full participants in the creation, deployment, alteration, and fading away of symbolic complexes."[78] His 1982 book, Symbols in Action, evokes the symbolic anthropology of Geertz, Schneider, with their focus on the context dependent meanings of cultural things, as an alternative to White and Steward's materialist view of culture.[79] In his 1991 textbook, Reading the Past: Current Approaches to Interpretation in Archaeology Hodder argued that archeology is more closely aligned to history than to anthropology.[80]

Cultural Anthropology and Cultural Studies

In the 1940s Robert Redfield and students of Julian Steward pioneered "community studies," namely, the study of distinct communities (whether identified by race, ethnicity, or economic class) in Western or "Westernized" societies, especially cities. They thus encountered the antagonisms 19th century critics described using the terms "high culture" and "low culture." These 20th century anthropologists struggled to describe people who were politically and economically inferior but not, they believed, culturally inferior. Oscar Lewis proposed the concept of a "culture of poverty" to describe the cultural mechanisms through which people adapted to a life of economic poverty. Other anthropologists and sociologists began using the term "sub-culture" to describe culturally distinct communities that were part of larger societies.

One important kind of subculture is that formed by an immigrant community. In dealing with immigrant groups and their cultures, there are various approaches:

- Leitkultur (core culture): A model developed in Germany by Bassam Tibi. The idea is that minorities can have an identity of their own, but they should at least support the core concepts of the culture on which the society is based.

- Melting Pot: In the United States, the traditional view has been one of a melting pot where all the immigrant cultures are mixed and amalgamated without state intervention.

- Monoculturalism: In some European states, culture is very closely linked to nationalism, thus government policy is to assimilate immigrants, although recent increases in migration have led many European states to experiment with forms of multiculturalism.

- Multiculturalism: A policy that immigrants and others should preserve their cultures with the different cultures interacting peacefully within one nation.

The way nation states treat immigrant cultures rarely falls neatly into one or another of the above approaches. The degree of difference with the host culture (i.e., "foreignness"), the number of immigrants, attitudes of the resident population, the type of government policies that are enacted, and the effectiveness of those policies all make it difficult to generalize about the effects. Similarly with other subcultures within a society, attitudes of the mainstream population and communications between various cultural groups play a major role in determining outcomes. The study of cultures within a society is complex and research must take into account a myriad of variables.

Independently, in the United Kingdom, sociologists and other scholars influenced by Marxism, such as Stuart Hall and Raymond Williams, developed "Cultural Studies." Following 19 century Romantics, they identified "culture" with consumption goods and leisure activities (such as art, music, film, food, sports, and clothing). Nevertheless, they understood patterns of consumption and leisure to be determined by relations of production, which led them to focus on class relations and the organization of production.[81][82] In the United States, "Cultural Studies" focuses largely on the study of popular culture, that is, the social meanings of mass-produced consumer and leisure goods.

Cultural change

Cultural invention has come to mean any innovation that is new and found to be useful to a group of people and expressed in their behavior but which does not exist as a physical object. Humanity is in a global "accelerating culture change period", driven by the expansion of international commerce, the mass media, and above all, the human population explosion, among other factors. (See The Third Wave.)

Cultures are internally affected by both forces encouraging change and forces resisting change. These forces are related to both social structures and natural events, and are involved in the perpetuation of cultural ideas and practices within current structures, which themselves are subject to change[83]. (See structuration.)

Social conflict and the development of technologies can produce changes within a society by altering social dynamics and promoting new cultural models, and spurring or enabling generative action. These social shifts may accompany ideological shifts and other types of cultural change. For example, the U.S. feminist movement involved new practices that produced a shift in gender relations, altering both gender and economic structures. Environmental conditions may also enter as factors. Changes include following for the film local hero. For example, after tropical forests returned at the end of the last ice age, plants suitable for domestication were available, leading to the invention of agriculture, which in turn brought about many cultural innovations and shifts in social dynamics[84].

Cultures are externally affected via contact between societies, which may also produce -- or inhibit -- social shifts and changes in cultural practices. War or competition over resources may impact technological development or social dynamics. Additionally, cultural ideas may transfer from one society to another, through diffusion or acculturation. In diffusion, the form of something (though not necessarily its meaning) moves from one culture to another. For example, hamburgers, mundane in the United States, seemed exotic when introduced into China. "Stimulus diffusion" (the sharing of ideas) refers to an element of one culture leading to an invention or propagation in another. "Direct Borrowing" on the other hand tends to refer to technological or tangible diffusion from one culture to another. Diffusion of innovations theory presents a research-based model of why and when individuals and cultures adopt new ideas, practices, and products.

Acculturation has different meanings, but in this context refers to replacement of the traits of one culture with those of another, such has happened to certain Native American tribes and to many indigenous peoples across the globe during the process of colonization. Related processes on an individual level include assimilation (adoption of a different culture by an individual) and transculturation.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2001). Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ Kroeber, A. L. and C. Kluckhohn, 1952. Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions.

- ^ a b Arnold, Matthew. 1869. Culture and Anarchy.

- ^ Williams (1983), p.90. Cited in Shuker, Roy (1994). Understanding Popular Music, p.5. ISBN 0-415-10723-7.

- ^ Bakhtin 1981, p.4

- ^ McClenon, p.528-529

- ^ Michael Eldridge, "The German Bildung Tradition" http://www.philosophy.uncc.edu/mleldrid/SAAP/USC/pbt1.html

- ^ "Adolf Bastian", Today in Science History; "Adolf Bastian", Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Tylor, E.B. 1874. Primitive culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art, and custom.

- ^ A. L. Kroeber 1917 "The Superorganic" American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 19, No. 2 pp. 163-213

- ^ Gerald Weiss 1973 "A Scientific Concept of Culture" in American Anthropologist 75(5): 1382

- ^ Franz Boas 1940 [1920] "The Methods of Ethnology", in Race, Language and Culture ed. George Stocking. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 284

- ^ Franz Boas 1940 [1932] "The Aims of Anthropological Research", in Race, Language and Culture ed. George Stocking. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 253

- ^ Kroeber, Alfred L. 1948 Anthropology: Race, Language, Culture, Psychology, Prehistory revised edition. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, Inc. p. 261

- ^ Franz Boas 1907 "Anthropology" in A Franz Boas Reader: The Shaping of American Anthropology 1883-1911 ed. George Stocking Jr. 267-382

- ^ Boas, Franz 1920 "The Methods of Ethnology" in Race, Language, and Culture. ed. George Stocking Jr. 1940 Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 281-289

- ^ Boas, Franz 1909 "Decorative Designs in Alaskan Needlecases: A Study in the History of Conventional designs Based on Materials in the U.S. National Museum" in Race, Language, and Culture. ed. George Stocking Jr. 1940 Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 564-592

- ^ Wissler, Clark (ed.) (1975) Societies of the Plains Indians AMS Press, New York, ISBN 0-404-11918-2 , Reprint of v. 11 of Anthropological papers of the American Museum of Natural History, published in 13 pts. from 1912 to 1916.

- ^ Kroeber, Alfred L. (1939) Cultural and Natural Areas of Native North America University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

- ^ Dyk, Walter 1938 Left Handed, Son of Old Man Hat, by Walter Dyk. Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press.

- ^ Lewis, Oscar 1961 The Children of Sanchez. New York: Vintage Books.

- ^ Lewis, Oscar 1964 Pedro Martinez. New York: Random House.

- ^ Mintz, Sidney 1960 Worker in the Cane: A Puerto Rican Life History. Yale Caribbean Series, vol. 2. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ^ Radin, Paul 1913 "Personal Reminiscences of a Winnebago Indian," in Journal of American Folklore 26: 293-318

- ^ Radin, Paul 1963 The Autobiography of a Winnebago Indian. New York: Dover Publications

- ^ Sapir, Edward 1922 "Sayach'apis, a Nootka Trader" in Elsie Clews Parsons, American Indian Life. New York: B.W. Huebesh.

- ^ Simmons, Leo, ed. 1942 Sun Chief: The Autobiography of a Hopi Indian. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ^ Benedict, Ruth. Patterns of Culture. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1934.

- ^ Benedict, Ruth. The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture. Rutland, VT and Tokyo, Japan: Charles E. Tuttle Co. 1954 orig. 1946.

- ^ Margaret Mead 1928 Coming of Age in Samoa

- ^ Ruth Benedict 1959 [1934] Patterns of Culture. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 46-47

- ^ Franz Boas 1940 [1932] “The Aims of Anthropological Research,” in Race, Language and Culture ed. George Stocking. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 256

- ^ Bashkow, Ira 2004 "A Neo-Boasian Conception of Cultural Boundaries" American Anthropologist 106(3): 446

- ^ Murdock, George, 1949 Social Structure New York: The Macmillan Company

- ^ Murdock, G. P. 1967. Ethnographic Atlas: A Summary. Pittsburgh: The University of Pittsburgh Press

- ^ Murdock, G. P. 1981. Atlas of World Cultures. Pittsburgh: The University of Pittsburgh Press.

- ^ Lévi-Strauss, Claude 1955 Tristes Tropiques Atheneum press

- ^ Lévi-Strauss, Claude Mythologiques I-IV (trans. John Weightman and Doreen Weightman);Le Cru et le cuit (1964), The Raw and the Cooked (1969); Du miel aux cendres (1966), From Honey to Ashes (1973); L'Origine des manières de table (1968) The Origin of Table Manners 1978); 'L'Homme nu (1971) The Naked Man (1981)

- ^ Bronislaw Malinowski 1944 The Scientific Theory of Culture

- ^ A.R. Radcliffe-Brown 1952 Structure and Function in Primitive Society

- ^ Talcott Parsons 1937, The Structure of Social Action

- ^ Talcott Parsons 1951, The Social System

- ^ Eric Wolf 1980 "They Divide and Subdivide and Call it Anthropology." The New York Times November 30:E9

- ^ Ira Bashkow, 2004 "A Neo-Boasian Conception of Cultural Boundaries," American Anthropologist 106(3):445-446

- ^ Appadurai, Arjun 1986 The Social Life of Things. (Edited) New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Appadurai, Arjun, 1996 Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- ^ Gupta, Akhil, and James Ferguson, 1992, "Beyond 'Culture': Space, Identity, and the Politics of Difference," Cultural Anthropology 7(1): 6-23

- ^ Marcus, George E. 1995 “Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography.” In Annual Review of Anthropology 24: 95-117

- ^ Wolf, Eric 1982 Europe and the people without history. Berkeley: The University of California Press.

- ^ Clifford Geertz 1973 The Interpretaion of Cultures New York: Basic Books

- ^ David Schneider 1968 American Kinship: A Cultural Account Chicago: University of Chicago press

- ^ Roy Wagner 1980 American Kinship: A Cultural Account Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- ^ Janet Dolgin, David Kemnitzer, and David Schneider, eds. Symbolic Anthropology: a Reader in the Study of Symbols and Meanings

- ^ Victor Turner 1967 The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual Ithaca:Cornell University Press

- ^ White, L. 1949. The Science of Culture: A study of man and civilization.

- ^ Leslie White, 1943 "Energy and the Evolution of Culture." American Anthropologist 45: 339

- ^ Leslie White, 1949 "Ethnological Theory." In Philosophy for the Future: The Quest of Modern Materialism. R. W. Sellars, V.J. McGill, and M. Farber, eds. Pp. 357-384. New York: Macmillan.

- ^ Julian Steward 1938 Basin Plateau Aboriginal Socio-political Groups (Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, No 20)

- ^ Julian Steward 1955 Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution University of Illinois Press

- ^ Dell Hymes 1969 Reinventing Anthropology p. 11

- ^ Dell Hymes 1969 Reinventing Anthropology p. 42

- ^ Dell Hymes 1969 Reinventing Anthropology p. 43

- ^ Sidney Mintz 1985 Sweetness and Power New York:Viking Press

- ^ Robert Murphy 1971 The Dialectics of Social Life New york: Basic Books

- ^ Marshall Sahlins 1976 Culture and Practical Reason Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- ^ Eric Wolf 1971 Peasant Wars of the Twentieth Century

- ^ Eric Wolf, 1982 Europe and the People Without History Berkeley: University of California Press

- ^ V. Gordon Childe 1929 The Danube in Prehistory Oxford: Clarendon Press

- ^ By R. Lee Lyman and Michael J. O'Brien, 2003 W.C. McKern and the Midwestern Taxonomic Method. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa

- ^ Colin Renfrew and Paul Bahn, 2008 Archeology: Theories, Methods and Practice Fifth edition. New York: Thames and Hudson. p. 470

- ^ Walter Taylor 1948 A Study of Archeology Memoir 69, American Anthropological Association, reprinted, Carbondale Il: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967. p. 96

- ^ Walter Taylor 1948 A Study of Archeology Memoir 69, American Anthropological Association, reprinted, Carbondale Il: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967. p. 100

- ^ Patty Jo Watson 1995 "Archeology, Anthropology, and the Culture Concept" in American Anthropologist 97(4) p.685

- ^ Robert Dunnel 1986 "Five Decades of American Archeology" in American Archeology past and Future: A Celebration of the Society for American Archeology, 1935-1985. D. Meltzer and J. Sabloff, eds. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. p.36

- ^ Lewish Binford 1962 "Archeology as Anthropology" in American Antiquity 28(2):218; see White 1959 The Evolution of Culture New York:McGraw Hill p.8

- ^ Lewish Binford 1962 "Archeology as Anthropology" in American Antiquity 28(2):218; see Steward 1955 Theory of Culture Change. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- ^ Patty Jo Watson 1995 "Archeology, Anthropology, and the Culture Concept" in American Anthropologist 97(4) p.684

- ^ Patty Jo Watson 1995 "Archeology, Anthropology, and the Culture Concept" in American Anthropologist 97(4) p.687-6874

- ^ Ian Hodder 1982 Symbols in action: ethnoarchaeological studies of material culture Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- ^ Ian Hodder 1986 Reading the past: current approaches to interpretation in archaeology Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- ^ name="Williams">Raymond Williams (1976) Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Rev. Ed. (NewYork: Oxford UP, 1983), pp. 87-93 and 236-8.

- ^ John Berger, Peter Smith Pub. Inc., (1971) Ways of Seeing

- ^ O'Neil, D. 2006. "Processes of Change".

- ^ Pringle, H. 1998. The Slow Birth of Agriculture. Science 282: 1446.