Kerala

Kerala

Kerala | |

|---|---|

state | |

| Nickname: God's Own Country | |

| |

| • Rank | 21st |

| Population (2001) | |

• Total | 31,838,619 |

| • Rank | 12th |

| Website | kerala.gov.in |

| ‡ 140 elected, 1 nominated | |

Kerala (Malayalam: Template:Kerala in Malayalam?; Kēraḷaṁ) is a union state located in the southwestern part of India. With an Arabian Sea coastline on the west, it is bordered on the north by Karnataka and by Tamil Nadu on the south and east. Major cities are Thiruvananthapuram (the capital), Kochi, and Kozhikode. The principal spoken language is Malayalam but many other languages are also spoken.

Kerala is mentioned in the ancient epic Mahabharata (800 BC) at several instances as a tribe, as a region and as a kingdom [citation needed]. The first written mention of Kerala is seen in a 3rd-century-BC rock inscription by emperor Asoka the Great, where it is mentioned as Keralaputra. This region formed part of ancient Tamilakam and was ruled by the Cheras. They had extensive trade relations with the Greeks, Romans and Arabs. In the 1st century AD Jewish immigrants arrived, and it is believed that St. Thomas the Apostle visited Kerala in the same century[1]. The Chera Kingdom and later the feudal Nair and Namboothiri Brahmin city-states became major powers in the region.[2] Early contact with Europeans gave way to struggles between colonial and native interests. The States Reorganisation Act of 1 November 1956 elevated Kerala to statehood.

Late-19th-century social reforms by Cochin and Travancore were expanded by post-independence governments. The state is known for achievements such as a literacy rate at 91%[3], which is among the highest in India, although still behind developing countries such as China (93%) or Thailand (93.9%).[4]. A survey conducted in 2005 by Transparency International ranked Kerala as the least corrupt state in the country.[5] The state confronts comparatively high suicide, alcoholism, and unemployment rates.[6] A large proportion of the population has moved away and Kerala is uniquely dependent on remittances, mainly from the Gulf countries.[7][8][9]

Etymology

Kerala has an uncertain etymology. Keralam may stem from the Classical Tamil chera-alam ("declivity of a hill or a mountain slope")[10] or chera alam ("Land of the Cheras").[11]: 2 Kerala may represent an imperfect Malayalam portmanteau fusing kera ("coconut palm tree") and alam ("land" or "location").[12]: 122 Natives of Kerala, known as Malayalis or Keralites, refer to their land as Keralam.

A 3rd-century-BC Asokan rock inscription mentioning a "Keralaputra" is the earliest surviving attestation to Kerala.[13] In written records, Kerala was mentioned in the Sanskrit epic Aitareya Aranyaka. Katyayana, Patanjali, Pliny the Elder, and the unknown author of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea displayed familiarity with Kerala.[14] In the last centuries BC, the region became famous among the Greeks and Romans for its spices, particularly black pepper.[13]

History

It is not certain if the region was inhabited during Neolithic times. However, there is evidence of the emergence of prehistoric pottery and granite burial monuments in the form of megalithic tombs in the 10th century BC; they resemble their counterparts in Western Europe and other parts of Asia. These are thought to be produced by speakers of a proto-Tamil language.[15] Kerala and Tamil Nadu once shared a common language, ethnicity and culture; this common area was known as Tamilakam.

According to legend, Kerala was an Asura-ruled kingdom under Mahabali. Onam, the national festival of Kerala, is dedicated to Maveli's memory. Another legend has Parasurama, an avatar of Mahavishnu, throwing his battle axe into the sea; from those waters, Kerala arose.[16]

The ancient Cheras, whose mother tongue and court language was Tamil, ruled Kerala from their capital at Vanchi. They were constantly at war with the neighbouring Chola and Pandya kingdoms. A Keralite identity, distinct from the Tamils and associated with the second Chera empire, became linguistically separate under the Kulasekhara dynasty (c. 800–1102). By the beginning of the 14th century, Ravi Varma Kulasekhara of Venad established a short-lived supremacy over southern India. After his death, Kerala became a conglomeration of warring chieftaincies, among which the most important were Calicut in the north and Venad in the south.

The Chera kings' dependence on trade meant that merchants from West Asia and Southern Europe established coastal posts and settlements in Kerala.[17]: 192–195, 303–307 The west Asian-semitic [18] Jewish, Christian, and Muslim immigrants[18] established Nasrani Mappila, Juda Mappila and Muslim Mappila communities.[18] [19] The Jews first arrived in Kerala in 573 BC.[20][21] The works of scholars and Eastern Christian writings state that Thomas the Apostle visited Muziris in Kerala in 52 AD to proselytize amongst Kerala's Jewish settlements.[22][23] However, the first verifiable migration of Jewish-Nasrani families to Kerala is of the arrival of Knanai Thoma in 345 AD .[24] Muslim merchants (Malik ibn Dinar) settled in Kerala by the 8th century AD and introduced Islam. After Vasco Da Gama's arrival in 1498, the Portuguese gained control of the lucrative pepper trade by subduing Keralite communities and commerce.[25][26]

Conflicts between Kozhikode (Calicut) and Kochi (Cochin) provided an opportunity for the Dutch to oust the Portuguese. In turn, the Dutch were ousted by Marthanda Varma of the Travancore Royal Family who routed them at the Battle of Colachel in 1741. In 1766, Hyder Ali, the ruler of Mysore invaded northern Kerala, capturing Kozhikode in the process. In the late 18th century, Tipu Sultan, Ali’s son and successor, launched campaigns against the expanding British East India Company; these resulted in two of the four Anglo-Mysore Wars. He ultimately ceded Malabar District and South Kanara to the Company in the 1790s. The Company then forged tributary alliances with Kochi (1791) and Travancore (1795). Malabar and South Kanara became part of the Madras Presidency.[27]

Kerala saw comparatively little defiance of the British Raj. Nevertheless, several rebellions occurred, including the 1946 Punnapra-Vayalar revolt,[28] and leaders like Velayudan Thampi Dalava, Kunjali Marakkar, and Pazhassi Raja earned their place in history and folklore. Many actions, spurred by such leaders as Vaikunda Swami[29], Sree Narayana Guru and Chattampi Swamikal, instead protested such conditions as untouchability; notable was the 1924 Vaikom Satyagraham. In 1936, Chitra Thirunal Bala Rama Varma of Travancore issued the Temple Entry Proclamation that opened Hindu temples to all castes; Cochin and Malabar soon did likewise. The 1921 Moplah Rebellion involved Mappila Muslims rioting against Hindus and the British Raj.[30]

After India gained its independence in 1947, Travancore and Cochin were merged to form Travancore-Cochin on 1 July 1949. On 1 January 1950 (Republic Day), Travancore-Cochin was recognised as a state. The Madras Presidency was organised to form Madras State several years prior, in 1947. Finally, the Government of India's 1 November 1956 States Reorganisation Act inaugurated the state of Kerala, incorporating Malabar district, Travancore-Cochin (excluding four southern taluks, which were merged with Tamil Nadu), and the taluk of Kasargod, South Kanara.[31] A new legislative assembly was also created, for which elections were first held in 1957. These resulted in a communist-led government through ballot—the world's first of its kind—headed by E.M.S. Namboodiripad.[31][32] Subsequent social reforms favoured tenants and labourers.[33]: 22–23, 43–44 Improvements in living standards, education, and life expectancy outpaced those of India as a whole.[citation needed]

Geography

Kerala is wedged between the Arabian Sea and the Western Ghats. Lying between north latitudes 8°18' and 12°48' and east longitudes 74°52' and 72°22',[34] Kerala is well within the humid equatorial tropics. Kerala’s coast runs for some 580 km (360 miles), while the state itself varies between 35 and 120 km (22–75 miles) in width. Geographically, Kerala can be divided into three climatically distinct regions: the eastern highlands (rugged and cool mountainous terrain), the central midlands (rolling hills), and the western lowlands (coastal plains). Located at the extreme southern tip of the Indian subcontinent, Kerala lies near the centre of the Indian tectonic plate; as such, most of the state is subject to comparatively little seismic and volcanic activity.[35] Pre-Cambrian and Pleistocene geological formations compose the bulk of Kerala’s terrain.

Eastern Kerala consists of high mountains, gorges and deep-cut valleys immediately west of the Western Ghats' rain shadow. Forty one of Kerala’s west-flowing rivers, and three of its east-flowing ones originate in this region. The Western Ghats form a wall of mountains interrupted only near Palakkad, where the Palakkad Gap breaks through to provide access to the rest of India. The Western Ghats rises on average to 1,500 m (4920 ft) above sea level, while the highest peaks may reach to 2,500 m (8200 ft). Just west of the mountains lie the midland plains comprising central Kerala, dominated by rolling hills and valleys.[34] Generally ranging between elevations of 250–1,000 m (820–3300 ft), the eastern portions of the Nilgiri and Palni Hills include such formations as Agastyamalai and Anamalai.

Kerala’s western coastal belt is relatively flat, and is criss-crossed by a network of interconnected brackish canals, lakes, estuaries, and rivers known as the Kerala Backwaters. Lake Vembanad—Kerala’s largest body of water—dominates the Backwaters; it lies between Alappuzha and Kochi and is more than 200 km² in area. Around 8% of India's waterways (measured by length) are found in Kerala.[36] The most important of Kerala’s forty four rivers include the Periyar (244 km), the Bharathapuzha (209 km), the Pamba (176 km), the Chaliyar (169 km), the Kadalundipuzha (130 km) and the Achankovil (128 km). The average length of the rivers of Kerala is 64 km. Most of the remainder are small and entirely fed by monsoon rains.[34] These conditions result in the nearly year-round water logging of such western regions as Kuttanad, 500 km² of which lies below sea level. As Kerala's rivers are small and lack deltas, they are more prone to environmental factors. Kerala's rivers face many problems, including summer droughts, the building of large dams, sand mining, and pollution.

Climate

With 120–140 rainy days per year, Kerala has a wet and maritime tropical climate influenced by the seasonal heavy rains of the southwest summer monsoon.[37]: 80 In eastern Kerala, a drier tropical wet and dry climate prevails. Kerala's rainfall averages 3,107 mm annually. Some of Kerala's drier lowland regions average only 1,250 mm; the mountains of eastern Idukki district receive more than 5,000 mm of orographic precipitation, the highest in the state.

In summers, most of Kerala is prone to gale force winds, storm surges, cyclone-related torrential downpours, occasional droughts, and rises in sea level and storm activity resulting from global warming.[38]: 26, 46, 52 Daily average high 36.7 °C; low 19.8 °C.[34] Mean annual temperatures range from 25.0–27.5 °C in the coastal lowlands to 20.0–22.5 °C in the eastern highlands.[38]: 65

Flora and fauna

Much of Kerala's notable biodiversity is concentrated and protected in the Agasthyamalai Biosphere Reserve in the eastern hills. Almost a fourth of India's 10,000 plant species are found in the state. Among the almost 4,000 flowering plant species (1,272 of which are endemic to Kerala and 159 threatened) are 900 species of highly sought medicinal plants.[39][40]: 11

Its 9,400 km² of forests include tropical wet evergreen and semi-evergreen forests (lower and middle elevations—3,470 km²), tropical moist and dry deciduous forests (mid-elevations—4,100 km² and 100 km², respectively), and montane subtropical and temperate (shola) forests (highest elevations—100 km²). Altogether, 24% of Kerala is forested.[40]: 12 Two of the world’s Ramsar Convention listed wetlands—Lake Sasthamkotta and the Vembanad-Kol wetlands—are in Kerala, as well as 1455.4 km² of the vast Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. Subjected to extensive clearing for cultivation in the 20th century,[41]: 6–7 much of the remaining forest cover is now protected from clearfelling. Kerala's fauna are notable for their diversity and high rates of endemism: 102 species of mammals (56 of which are endemic), 476 species of birds, 202 species of freshwater fishes, 169 species of reptiles (139 of them endemic), and 89 species of amphibians (86 endemic).[39] These are threatened by extensive habitat destruction, including soil erosion, landslides, salinization, and resource extraction.[42]

Eastern Kerala’s windward mountains shelter tropical moist forests and tropical dry forests, which are common in the Western Ghats. Here, sonokeling (Indian rosewood), anjili, mullumurikku (Erythrina), and Cassia number among the more than 1,000 species of trees in Kerala. Other plants include bamboo, wild black pepper, wild cardamom, the calamus rattan palm (a type of climbing palm), and aromatic vetiver grass (Vetiveria zizanioides).[40]: 12 Living among them are such fauna as Asian Elephant, Bengal Tiger, Leopard (Panthera pardus), Nilgiri Tahr, Common Palm Civet, and Grizzled Giant Squirrel.[40]: 12, 174–175 Reptiles include the king cobra, viper, python, and crocodile. Kerala's birds are legion—Peafowl, the Great Hornbill, Indian Grey Hornbill, Indian Cormorant, and Jungle Myna are several emblematic species. In lakes, wetlands, and waterways, fish such as kadu (stinging catfish and Choottachi (Orange chromide—Etroplus maculatus; valued as an aquarium specimen) are found.[40]: 163–165

Subdivisions

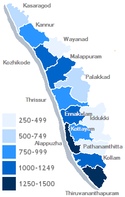

Kerala's fourteen districts are distributed among Kerala's three historical regions: Malabar (northern Kerala), Kochi (central Kerala), and Travancore (southern Kerala). Kerala's modern-day districts (listed in order from north to south) correspond to them as follows:

- Malabar: Kasaragod, Kannur, Wayanad, Kozhikode, Malappuram, Palakkad

- Kochi: Thrissur, Ernakulam

- Travancore: Kottayam, Idukki, Alappuzha, Pathanamthitta, Kollam, Thiruvananthapuram

Kerala comprises the regions of Central Travancore, Chera Nadu, Kuttanad, Malabar, Onattukara, Travancore, Valluvanadu, and Venad. Kerala's 14 revenue districts are subdivided into 62 taluks, 1453 revenue villages and 1007 Gram panchayats.

Mahé, a part of the Indian union territory of Puducherry (Pondicherry), is a coastal exclave surrounded by Kerala on all of its landward approaches. Thiruvananthapuram (Trivandrum) is the state capital and most populous city.[43] Kochi is the most populous urban agglomeration[44] and the major port city in Kerala. Kozhikode, Thrissur, and Kannur are the other major commercial centers of the state. The High Court of Kerala is located at Ernakulam. Kerala's districts, which serve as the administrative regions for taxation purposes, are further subdivided into 63 taluks; these have fiscal and administrative powers over settlements within their borders, including maintenance of local land records.

| Largest cities in Kerala (2001 Census of India estimate)[45] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | City\Town | District | Population | ||||||||

| 01 | Thiruvananthapuram | Thiruvananthapuram | 744,983 | ||||||||

| 02 | Kochi | Ernakulam | 595,575 | ||||||||

| 03 | Kozhikode | Kozhikode | 436,556 | ||||||||

| 04 | Kollam | Kollam | 361,029 | ||||||||

| 05 | Thrissur | Thrissur | 317,526 | ||||||||

| 06 | Alappuzha | Alappuzha | 187,495 | ||||||||

| 07 | Palakkad | Palakkad | 130,767 | ||||||||

| 08 | Thalassery | Kannur | 99,387 | ||||||||

| 09 | Ponnani | Malappuram | 87,495 | ||||||||

| 10 | Manjeri | Malappuram | 83,707 | ||||||||

Government

Like other Indian states, Kerala is governed through a parliamentary system of representative democracy; universal suffrage is granted to state residents. There are three branches of government. The unicameral legislature, known as the legislative assembly, comprises elected members and special office bearers (the Speaker and Deputy Speaker) elected by the members from among themselves. Assembly meetings are presided over by the Speaker and in his absence by the Deputy Speaker. Kerala has 140 Assembly constituencies. The state sends 20 members to the Lok Sabha and 9 to the Rajya Sabha, the Indian Parliament's upper house.

The constitutional head of state is the Governor of Kerala, who is appointed by the President of India. The executive authority is headed by the Chief Minister of Kerala, who is the de facto head of state and is vested with most of the executive powers; the Legislative Assembly's majority party leader is appointed to this position by the Governor. The Council of Ministers, which answers to the Legislative Assembly, has its members appointed by the Governor; the appointments receive input from the Chief Minister.

The judiciary comprises the Kerala High Court (including a Chief Justice combined with 26 permanent and two additional (pro tempore) justices) and a system of lower courts. The High Court of Kerala is the apex court for the state; it also hears cases from the Union Territory of Lakshadweep. Auxiliary authorities known as panchayats, for which local body elections are regularly held, govern local affairs.

The state's 2005–2006 budget was 219 billion INR.[46] The state government's tax revenues (excluding the shares from Union tax pool) amounted to 111,248 million INR in 2005, up from 63,599 million in 2000. Its non-tax revenues (excluding the shares from Union tax pool) of the Government of Kerala as assessed by the Indian Finance Commissions reached 10,809 million INR in 2005, nearly double the 6,847 million INR revenues of 2000.[47] However, Kerala's high ratio of taxation to gross state domestic product (GSDP) has not alleviated chronic budget deficits and unsustainable levels of government debt, impacting social services.[48]

Politics

Kerala hosts two major political alliances: the United Democratic Front (UDF—led by the Indian National Congress) and the Left Democratic Front (LDF—led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)). At present, the LDF is the ruling coalition in government; V.S. Achuthanandan of the CPI(M) is the Chief Minister of Kerala and Oommen Chandy of the UDF is the Chief Opposition leader.

Kerala is one of the few regions in the world where communist parties are democratically elected in a parliamentary democracy. Compared with most other Indians, Keralites are well versed and keen participants in the political process; many elections are decided by razor-thin margins of victory. Strikes, protests, rallies, and marches are ubiquitous.[49]

Economy

Since independence, Kerala was managed as a democratic socialist welfare economy. Since the 1990s, liberalisation of the mixed economy allowed onerous Licence Raj restrictions against the free market and foreign direct investment to be lightened, leading to economic expansion and job creation. In fiscal year 2004–2005, nominal gross state domestic product (GSDP) was ₹89,451.99 crore (US$11 billion).[50] Recent GSDP growth (9.2% in 2004–2005 and 7.4% in 2003–2004) has been robust compared to historical averages (2.3% annually in the 1980s and between 5.1%[51]: 8 and 5.99%[52] in the 1990s).[51]: 8 The state clocked 8.93% growth in enterprises from 1998 to 2005 compared with 4.80% nationally.[53] Relatively few such enterprises are major corporations or manufacturers.[38]: 49 Per-capita GSDP is ₹11,819 (US$140),[54] above the Indian average and far below the world average.[51]: 8 Kerala's Human Development Index rating is the highest in India.[55] This apparently paradoxical "Kerala phenomenon" or "Kerala model of development" of high human and low economic development results from the strong service sector.[38]: 48 [56]: 1 Kerala's economy depends on emigrants working in foreign countries (mainly in the Gulf countries such as Dubai or Bahrain) and remittances annually contribute more than a fifth of GSDP.[7][8][9]

The service sector (including tourism, public administration, banking and finance, transportation, and communications—63.8% of GSDP in 2002–2003) and the agricultural and fishing industries (together 17.2% of GSDP) dominate the economy.[52][57] Nearly half of Kerala's people are dependent on agriculture alone for income.[58] Some 600 varieties[40]: 5 of rice (Kerala's most important staple food and cereal crop)[59]: 5 are harvested from 3105.21 km² (a decline from 5883.4 km² in 1990)[59]: 5 of paddy fields; 688,859 tonnes are produced per annum.[58] Other key crops include coconut (899,198 ha), tea, coffee (23% of Indian production,[60]: 13 or 57,000 tonnes[60]: 6–7 ), rubber, cashews, and spices—including pepper, cardamom, vanilla, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Around 1.050 million fishermen haul an annual catch of 668,000 tonnes (1999–2000 estimate); 222 fishing villages are strung along the 590 km coast. Another 113 fishing villages dot the hinterland.

Traditional industries manufacturing such items as coir, handlooms, and handicrafts employ around one million people. Around 180,000 small-scale industries employ around 909,859 Keralites; 511 medium and large scale manufacturing firms are located in Kerala. A small mining sector (0.3% of GSDP)[57] involves extraction of ilmenite, kaolin, bauxite, silica, quartz, rutile, zircon, and sillimanite.[58] Home gardens and animal husbandry also provide work for hundreds of thousands of people. Other major sectors are tourism, manufacturing, and business process outsourcing. As of March 2002, Kerala's banking sector comprised 3341 local branches; each branch served 10,000 persons, lower than the national average of 16,000; the state has the third-highest bank penetration among Indian states.[61] Unemployment in 2007 was estimated at 9.4%;[62] underemployment, low employability of youths, and a 13.5% female participation rate are chronic issues.[63]: 5, 13 [64] Poverty rate figures range from 12.71%[65] to as high as 36%.[66] More than 45,000 residents live in slum conditions.[67]

Religions

About 55% of Malayalis are Hindus, 23% are Christians and 20% are Muslims. Most members of the ancient Jewish community in Kerala emigrated to Israel. Casteism is pervasive amongst the Hindus in Kerala. Historically, Christians were called Nasrani, an Arabic word, and most are identified as Roman Catholic, Jacobite, Syrian, or Protestants, etc. The legend is that the Christians in Kerala are descended from the converts St. Thomas who visited India in the first after Christ. However, most Christians are descended from the much later conversion efforts of the Portuguese, British and other Europeans in the last five hundred years. Islam arrived in Kerala with the first Arab traders who expanded, and then monopolized, the trade with West through Kozhikode. Later, many people converted to the new faith. Muslims in Kerala are also known as Moplah. These religious communities have lived together in peace and amicability, except for a few rare incidents.

The major pilgrimage centre for Hindus are located in Guruvayur, Sabarimala, Chottanikara. Christians have numerous churches across the state; some significant churches are located Kunnamkulam, Attingal, Alappuzha, etc. There are mosques are across the state; one famous mosque is located at Ponnani. Most Jews in Kerala live in the city of Kochi where they have a synagogue.

Transport

Kerala has Template:Km to mi of roads (4.2% of India's total). This translates to about Template:Km to mi of road per thousand population, compared to an all India average of Template:Km to mi. Virtually all of Kerala's villages are connected by road. Traffic in Kerala has been growing at a rate of 10–11% every year, resulting in high traffic and pressure on the roads. Kerala's road density is nearly four times the national average, reflecting the state's high population density. Kerala's annual total of road accidents is among the nation's highest.[68]

India's national highway network includes a Kerala-wide total of Template:Km to mi, which is 2.6% of the national total. There are eight designated national highways in the state. The Kerala State Transport Project (KSTP), which includes the GIS-based Road Information and Management Project (RIMS), is responsible for maintaining and expanding the Template:Km to mi of roadways that compose the state highways system; it also oversees major district roads.[69][70] Most of Kerala's west coast is accessible through two national highways, NH 47, and NH 17.

The state has three major international airports at Thiruvananthapuram, Kochi, and Kozhikode, that link the state with the rest of the nation and the world. Fourth international airport is coming up at Kannur,once operational Kannur international airport will be the largest airport in Kerala. The Cochin International Airport was the first Indian airport incorporated as a public limited company and is funded by nearly 10,000 Non Resident Indians from 30 countries.[71] The backwaters traversing the state are an important mode of inland navigation. The Indian Railways' Southern Railway line runs throughout the state, connecting all major towns and cities except those in the highland districts of Idukki and Wayanad. Kerala's major railway stations are Trivandrum Central,Trichur Junction, Kollam Junction, Ernakulam Junction, Kannur, Kozhikode,Guruvayur, Shoranur Junction, and Palakkad.

Demographics

The 31.8 million[72] Keralites are predominantly of Malayali ethnicity, while the rest is mostly made up of Jewish and Arab elements in both culture and ancestry. Kerala's 321,000 indigenous tribal Adivasis, 1.10% of the population, are concentrated in the east.[73]: 10–12 Malayalam is Kerala's official language; Tamil and various Adivasi languages are also spoken by ethnic minorities.

Kerala is home to 3.44% of India's people; at 819 persons per km², its land is nearly three times as densely settled as the rest of India, which is at a population density of 325 persons per km².[74] Kerala's rate of population growth is India's lowest,[75] and Kerala's decadal growth (9.42% in 2001) is less than half the all-India average of 21.34%.[76] Whereas Kerala's population more than doubled between 1951 and 1991 by adding 15.6 million people to reach 29.1 million residents in 1991, the population stood at less than 32 million by 2001. Kerala's coastal regions are the most densely settled, leaving the eastern hills and mountains comparatively sparsely populated.[34]

Women compose 51.42% of the population.[77]: 26 Kerala's principal religions are Hinduism (56.2%%), Islam (24.70%), and Christianity (19.00%).[78] Remnants of a once substantial Cochin Jewish population also practice Judaism. In comparison with the rest of India, Kerala experiences relatively little sectarianism.[79]

Lindberg Anna says Kerala's society is less patriarchal than the rest of the Third World.[need quotation to verify][80]: 18–19 Kerala government states gender relations are among the most equitable in India and the Third World[need quotation to verify][81], despite discrepancies among low caste men and women.[80]: 1 Certain Hindu communities such as the Nairs, some Ezhavas and the Muslims around Kannur used to follow a traditional matrilineal system known as marumakkathayam, although this practice ended in the years after Indian independence. Other Muslims, Christians, and some Hindu castes such as the Namboothiris and the Ezhavas follow makkathayam, a patrilineal system.[82] Owing to the former matrilineal system, women in Kerala enjoy a high social status.[13]

Kerala's human development indices—elimination of poverty, primary level education, and health care—are among the best in India. According to a 2005-2006 national survey, Kerala has one of the highest literacy rates (89.9%) among Indian states[3] and life expectancy (73 years) was among the highest in India in 2001.[83] Kerala's rural poverty rate fell from 69% (1970–1971) to 19% (1993–1994); the overall (urban and rural) rate fell 36% between the 1970s and 1980s.[84] By 1999–2000, the rural and urban poverty rates dropped to 10.0% and 9.6% respectively.[85] These changes stem largely from efforts begun in the late 19th century by the kingdoms of Cochin and Travancore to boost social welfare.[86][87] This focus was maintained by Kerala's post-independence government.[55][38]: 48

Health

Kerala's healthcare system has garnered international acclaim. The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organization designated Kerala the world's first "baby-friendly state".[citation needed] For example, more than 95% of Keralite births are hospital-delivered.[88]: 6 Aside from ayurveda (both elite and popular forms),[89]: 13 siddha, and unani, many endangered and endemic modes of traditional medicine, including kalari, marmachikitsa,[89]: 17 and vishavaidyam, are practiced. These propagate via gurukula discipleship,,[89]: 5–6 and comprise a fusion of both medicinal and supernatural treatments,[89]: 15 and are partly responsible for drawing increasing numbers of medical tourists.

A steadily aging population (11.2% of Keralites are over age 60[55]) and low birthrate[90] (18 per 1,000)[91] make Kerala one of the few regions of the Third World to have undergone the "demographic transition" characteristic of such developed nations as Canada, Japan, and Norway.[56]: 1 In 1991, Kerala's total fertility rate (children born per women) was the lowest in India. Hindus had a TFR of 1.66, Christians 1.78, and Muslims 2.97.[92] Kerala's female-to-male ratio (1.058) is significantly higher than that of the rest of India.[83][56]: 2 The same is true of its sub-replacement fertility level and infant mortality rate (estimated at 12[91][38]: 49 to 14[93]: 5 deaths per 1,000 live births).

However, Kerala's morbidity rate is higher than that of any other Indian state—118 (rural Keralites) and 88 (urban) per 1,000 people. The corresponding all India figures are 55 and 54 per 1,000, respectively.[93]: 5 Kerala's 13.3% prevalence of low birth weight is substantially higher than that of First World nations.[91] Outbreaks of water-borne diseases such as diarrhoea, dysentery, hepatitis, and typhoid among the more than 50% of Keralites who rely on 3 million water wells is a problem worsened by the widespread lack of sewers.[94]: 5–7

Education

The antiquity and robustness of Kerala's education system[citation needed] is underscored by her status as one of the most literate states in the country. The local dynastic precursors of modern-day Kerala made significant contributions to the progress on education by sponsoring sabha mathams that imparted Vedic knowledge. Apart from kalaris, which taught martial arts, there were village schools run by Ezhuthachans or Asans. The history of western education in Kerala can be traced to Christian missionaries who set up numerous schools and colleges.

The schools and colleges in Kerala are run by the government or private trusts or individuals. Each school is affiliated with either the Indian Certificate of Secondary Education (ICSE), the Central Board for Secondary Education (CBSE), or the Kerala State Education Board. English is the language of instruction in most private schools, while government run schools offer English or Malayalam as medium. After 10 years of secondary schooling, students typically enroll at Higher Secondary School in one of the three streams—liberal arts, commerce or science. Upon completing the required coursework, students can enroll in general or professional degree programmes. Kerala topped the Education Development Index (EDI) among 21 major states in India in year 2006-2007. EDI is calculated using indicators such as access, infrastructure, teachers and outcome.[95]

Thiruvananthapuram, one of the state's major academic hubs, hosts the University of Kerala and several professional education colleges, including 15 engineering colleges, three medical colleges, three Ayurveda colleges, two colleges of homeopathy, six other medical colleges, and several law colleges.[96] Trivandrum Medical College, Kerala's premier health institute, one of the finest in the country, is being upgraded to the status of an All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS). The College of Engineering, Trivandrum is one of the prominent engineering institutions in the state. The Asian School of Business and IIITM-K are two of the other premier management study institutions in the city, both situated inside Technopark. The Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology, first of its kind in India, is situated in the state capital.

Kochi is another major educational hub. The Cochin University of Science and Technology (also known as "Cochin University") is situated in the suburb of the city. Most of the city's colleges offering tertiary education are affiliated to the Mahatma Gandhi University. Other national educational institutes in Kochi include the Central Institute of Fisheries Nautical and Engineering Training, the National University of Advanced Legal Studies, the National Institute of Oceanography, Central Institute of Fisheries Technology and the Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute.The only College of Fisheries in the State is situated at Panangad, a suburban area of the City. The College comes under the Kerala Agricultural University.

The district of Thrissur holds some premier institutions in Kerala. Kerala Agricultural University is situated in this city. Thrissur Medical College, The Government Engineering College, Govt. Law College, Ayurveda College, Govt.Fine Arts College, College of Co-operation & Banking and Management, College of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, College of Horticulture, College of Forestry etc are situated in Thrissur. Thrissur is also a main center of coaching for the entrance examinations for engineering and medicine.

Kottayam also acts as a main educational hub. According to the 1991 census, Kottayam District of Kerala is the first district to achieve full literacy rate in the whole of India. Mahatma Gandhi University, CMS College(the first institution to start English education in Southern India), Medical College, Kottayam, and the Labour India Educational Research Center are some of the important educational institutions in the district.

Kozhikode is home to two of the premier educational institutions in the country; the IIMK, one of the seven Indian Institutes of Management., and the premier National Institute of Technology Calicut, the NITC. Calicut Medical College, the second medical college in Kerala is affiliated to the University of Calicut and serves 2/5 of the population of Kerala. Government Law College situated in outskirts of Calicut City is owned by the Government of Kerala and caters to the needs of the entire north Malabar region of Kerala. Pothanicad, a village in Ernakulam district is the first panchayath in India that achieved 100% literacy.

Culture

Kerala's culture is derived from both a Tamil-heritage region known as Tamilakam and southern coastal Karnataka. Later, Kerala's culture was elaborated upon through centuries of contact with neighboring and overseas cultures.[97] Native performing arts include koodiyattom (a 2000 year old Sanskrit theatre tradition, officially recognised by UNESCO as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity[98]), kathakali—from katha ("story") and kali ("performance")—and its offshoot Kerala natanam, koothu (akin to stand-up comedy), mohiniaattam ("dance of the enchantress"), thullal, padayani, and theyyam.

Other forms of art are more religious or tribal in nature. These include chavittu nadakom, oppana (originally from Malabar), which combines dance, rhythmic hand clapping, and ishal vocalisations. However, many of these art forms largely play to tourists or at youth festivals, and are not as popular among most ordinary Keralites. These people look to more contemporary art and performance styles, including those employing mimicry and parody.

Kerala's music also has ancient roots. Carnatic music dominates Keralite traditional music. This was the result of Swathi Thirunal Rama Varma's popularisation of the genre in the 19th century.[99][100] Raga-based renditions known as sopanam accompany kathakali performances. Melam (including the paandi and panchari variants) is a more percussive style of music; it is performed at Kshetram centered festivals using the chenda. Melam ensembles comprise up to 150 musicians, and performances may last up to four hours. Panchavadyam is a different form of percussion ensemble, in which up to 100 artists use five types of percussion instrument. Kerala has various styles of folk and tribal music. The popular music of Kerala is dominated by the filmi music of Indian cinema. Kerala's visual arts range from traditional murals to the works of Raja Ravi Varma, the state's most renowned painter.

Kerala has its own Malayalam calendar, which is used to plan agricultural and religious activities. Kerala's cuisine is typically served as a sadhya on green banana leaves. Such dishes as idli, payasam, pulisherry, puttucuddla, puzhukku, rasam, and sambar are typical. Keralites—both men and women alike—traditionally don flowing and unstitched garments. These include the mundu, a loose piece of cloth wrapped around men's waists. Women typically wear the sari, a long and elaborately wrapped banner of cloth, wearable in various styles. Presently the North Indian dresses such as Salwar Kameez has also become very popular amongst women in Kerala.

The elephants are an integral part of the daily life in Kerala. These Indian elephants are loved, revered, groomed and given a prestigious place in the state's culture. Elephants in Kerala are often referred to as the 'sons of the sahya.' The elephant is the state animal of Kerala and is featured on the emblem of the Government of Kerala.

Language

The predominant spoken language in Kerala is Malayalam, most of whose speakers live in Kerala. Malayalam literature is ancient in origin, and includes such figures as the 14th century Niranam poets (Madhava Panikkar, Sankara Panikkar and Rama Panikkar), and the 17th century poet Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan whose works mark the dawn of both modern Malayalam language and indigenous Keralite poetry. The "triumvirate of poets" (Kavithrayam), Kumaran Asan, Vallathol Narayana Menon, and Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer, are recognised for moving Keralite poetry away from archaic sophistry and metaphysics, and towards a more lyrical mode.

In the second half of the 20th century, Jnanpith awardees like G. Sankara Kurup, S. K. Pottekkatt, Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai and M. T. Vasudevan Nair have made valuable contributions to the Malayalam literature. Later, such Keralite writers as O. V. Vijayan, Kamaladas, M. Mukundan, and Booker Prize winner Arundhati Roy, whose 1996 semi-autobiographical bestseller[101] The God of Small Things is set in the Kottayam town of Ayemenem, have gained international recognition.[102][103]

Media

Dozens of newspapers are published in Kerala; they are printed in nine major languages.[104] The principal languages of publication are Malayalam and English. The most widely circulating Malayalam-language newspapers include Mathrubhumi, Manorama, Deepika, Kerala Kaumudi,Madhyamam and Deshabhimani. Among major Malayalam periodicals are India Today Malayalam, Grihalakshmi, Veedu, Vanitha, Chithrabhumi, Kanyaka, and Bhashaposhini. A Malayalam version of Google News was launched in September 2008.[105]

Doordarshan is the state-owned television broadcaster. Multi system operators provide a mix of Malayalam, English, and international channels via cable television.There are 17 malayalam channels which makes the countries maximum number in regional language.Asianet,Amrita TV,Surya TV and Kairali TV are among the Malayalam-language channels that compete with the major national channels. All India Radio, the national radio service, reaches much of Kerala via its Thiruvananthapuram, Thrissur & Alappuzha, Malayalam-language broadcasters. BSNL, Reliance Infocomm, Tata Indicom, Vodafone and Airtel compete to provide cellular phone services. Broadband internet is available in most of the towns and cities and is provided by different agencies like the state-run Kerala Telecommunications (which is run by BSNL) and by other private companies like Asianet Satellite communications, VSNL. BSNL provides 2 Mbit/s and 8 Mbit/s broadband service in most of the cities. Kerala accounts for the highest number of PC users and software engineers in India.[citation needed]

A substantial Malayalam film industry effectively competes against both Bollywood and Hollywood. Television (especially "mega serials" and cartoons) and the Internet have affected Keralite culture. Yet Keralites maintain high rates of newspaper and magazine subscriptions; 50% spend an average of about seven hours a week reading novels and other books. A sizeable "people's science" movement has taken root in the state, and such activities as writers' cooperatives are becoming increasingly common.[106][56]: 2

Sports

Several ancient ritualised arts are Keralite in origin. These include kalaripayattu—kalari ("place", "threshing floor", or "battlefield") and payattu ("exercise" or "practice"). Among the world's oldest martial arts, oral tradition attributes kalaripayattu's emergence to Parasurama. Other ritual arts include theyyam and poorakkali. However, larger numbers of Keralites follow sports such as cricket, kabaddi, soccer, and badminton. Dozens of large stadiums, including Kochi's Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium and Thiruvananthapuram's Chandrashekaran Nair Stadium, attest to the mass appeal of such sports among Keralites.

Kerala has been the athletics powerhouse of India for decades, and several Keralite athletes have attained world-class status, including P. T. Usha, Suresh Babu, Shiny Wilson, K. M. Beenamol, M. D. Valsamma and Anju Bobby George.

Football is the most popular sport in the state but it has an illustrious history in other sports/games, including cricket. Some notable football stars from Kerala include I. M. Vijayan, V. P. Sathyan, and Jo Paul Ancheri. Volleyball, another popular sport, is often played on makeshift courts on sandy beaches along the coast. Jimmy George, born in Peravoor, Kannur, was a notable Indian volleyball player, regarded in his prime as among the world's ten best players.[107]

It is from the 1990s that cricket started growing in popularity. The 21st century saw two Kerala Ranji Trophy players gain test selection. Shanthakumaran Sreesanth, born in Kothamangalam, has represented India since 2005, and is the most successful cricketer from Kerala.[108]. Among less successful Keralite cricketers is Tinu Yohannan, son of Olympic long jumper T. C. Yohannan.[109][110][111]

Tourism

Kerala, situated on the lush and tropical Malabar Coast, is one of the most popular tourist destinations in India. Named as one of the "ten paradises of the world" and "50 places of a lifetime" by the National Geographic Traveler magazine, Kerala is especially known for its ecotourism initiatives.[112][113] Its unique culture and traditions, coupled with its varied demographics, has made Kerala one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world. Growing at a rate of 13.31%, the state's tourism industry is a major contributor to the state's economy.[114]

Until the early 1980s, Kerala was a relatively unknown destination;[115] most tourist circuits focused on North India. Aggressive marketing campaigns launched by the Kerala Tourism Development Corporation, the government agency that oversees tourism prospects of the state, laid the foundation for the growth of the tourism industry. In the decades that followed, Kerala's tourism industry was able to transform the state into one of the niche holiday destinations in India. The tagline Kerala- God's Own Country, originally coined by Vipin Gopal, has been widely used in Kerala's tourism promotions and soon became synonymous with the state. In 2006, Kerala attracted 8.5 million tourist arrivals, an increase of 23.68% over the previous year, making the state one of the fastest-growing destinations in the world.[116]

Popular attractions in the state include the beaches at Kovalam, Cherai and Varkala; the hill stations of Munnar, Nelliampathi, Ponmudi and Wayanad; and national parks and wildlife sanctuaries at Periyar and Eravikulam National Park. The "backwaters" region, which comprises an extensive network of interlocking rivers, lakes, and canals that centre on Alleppey, Kollam, Kumarakom, and Punnamada (where the annual Nehru Trophy Boat Race is held in August), also see heavy tourist traffic. Heritage sites, such as the Padmanabhapuram Palace and the Mattancherry Palace, are also visited. Cities such as Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram are popular centres for their shopping and traditional theatrical performances. During early summer, the Thrissur Pooram is conducted, attracting foreign tourists who are largely drawn by the festival's elephants and celebrants.[117]

See also

Notes

Citations

- ^ "Kerala." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 18 Jun. 2008 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/315300/Kerala>.

- ^ "Early history of Kerala". Government of Kerala. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ a b 2005-2006 National Family Health Survey

- ^ See List of countries by literacy rate.

- ^ "India Corruption Study — 2005". Transparency International. 2005. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The extent of problem of Mental Health in the State". Kerala State Mental Health Authority. Government of Kerala. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ a b K.P. Kannan, K.S. Hari (2002). "Kerala's Gulf connection: Emigration, remittances and their macroeconomic impact 1972-2000".

- ^ a b S Irudaya Rajan, K.C. Zachariah (2007). "Remittances and its impact on the Kerala Economy and Society" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Jobs Abroad Support 'Model' State in India". New York Times. 2007.

- ^ Menon AS (1967). A Survey of Kerala History. Sahitya Pravarthaka Cooperative Society.

- ^ George KM (1968). A Survey of Malayalam Literature. Asia Publishing House.

- ^ Dobbie A (2006). India: The Elephant's Blessing. Melrose Press. ISBN 1-9052-2685-3. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ a b c "Kerala." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 8 June 2008

- ^ Pliny's Naturalis Historia, Book 6, Chapter 26

- ^ Government of Kerala 2005.

- ^ Aiya VN (1906). The Travancore State Manual. Travancore Government Press. pp. 210–212. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ Iyengar PTS (2001). History Of The Tamils: From the Earliest Times to 600 A.D. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 8-1206-0145-9. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ^ a b c * Bindu Malieckal (2005) Muslims, Matriliny, and A Midsummer Night's Dream: European Encounters with the Mappilas of Malabar, India; The Muslim World Volume 95 Issue 2

- ^ Milton J, Skeat WW, Pollard AW, Brown L (1982-08-31). The Indian Christians of St Thomas. Cambridge University Press. p. 171. ISBN 0-5212-1258-8.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ De Beth Hillel, David (1832). Travels (Madras publication).

- ^ Lord, James Henry (1977). The Jews in India and the Far East; Greenwood Press Reprint; ISBN.

- ^ Medlycott, A E. 1905 "India and the Apostle Thomas"; Gorgias Press LLC; ISBN

- ^ Thomas Puthiakunnel, (1973) "Jewish colonies of India paved the way for St. Thomas", The Saint Thomas Christian Encyclopedia of India, ed. George Menachery, Vol. II.

- ^ a b Mundadan AM (1984). Volume I: From the Beginning up to the Sixteenth Century (up to 1542). History of Christianity in India. Church History Association of India. Bangalore: Theological Publications.

- ^ Ravindran PN (2000). Black Pepper: Piper Nigrum. CRC Press. p. 3. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ Curtin PD (1984). Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge University Press. p. 144. ISBN 0-5212-6931-8.

- ^ Superintendent of Government Printing (1908). Imperial Gazetteer of India (Provincial Series): Madras. Calcutta: Government of India. p. 22. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ "Emergence of Nationalism: Punnapra-Vayalar revolt". Department of Public Relations (Government of Kerala). 2002. Archived from the original on 2005-02-23. Retrieved 2006-01-14.

- ^ www.education.kerala.gov.inTowards Modern Kerala, 10th Standard Text Book, Chapter 9, Page 101. See this Pdf

- ^ Qureshi, MN (1999). Pan-Islam in British Indian Politics: A Study of the Khilafat Movement, 1918–1924. Leiden [u.a.]: Brill. pp. 445–447. ISBN 9-0041-0538-7. OCLC 231706684.

- ^ a b Plunkett, Cannon & Harding 2001, p. 24.

- ^ Jose D (1998-03-19). "EMS Namboodiripad dead". Rediff. Press Trust of India. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Cheriyan O (2004). "Changes in the mode of labour due to shift in the land use pattern" (PDF). Centre for Development Studies. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ a b c d e Government of Kerala 2005b.

- ^ Map Showing Multi Hazard Zones in Kerala (Map). United Nations Development Programme. 2002. Archived from the original on 2006-11-08. Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- ^ Inland Waterways Authority of India 2005.

- ^ Chacko T (2002). "Temperature mapping, thermal diffusivity and subsoil heat flux at Kariavattom, Kerala". Proc Indian Acad Sci (Earth Planet Sci).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Brenkert A (2003). "Vulnerability and resilience of India and Indian states to climate change: a first-order approximation". Joint Global Change Research Institute.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Government of Kerala 2004f, p. 141.

- ^ a b c d e f Sreedharan TP (2004). "Biological Diversity of Kerala: A survey of Kalliasseri panchayat, Kannur district" (PDF). Centre for Development Studies. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ Jayarajan M (2004). "Sacred Groves of North Malabar" (PDF). Centre for Development Studies. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ Government of Kerala 2004f, pp. 142–145.

- ^ "World Gazetteer:India - largest cities (per geographical entity")

- ^ "World Gazetteer: India - largest cities (per geographical entity")

- ^ "Kerala". Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner. 2007-03-18. Retrieved 2008-07-23.

- ^ Budget at a Glance

- ^ Finance Commission (Ministry of Finance, Government of India)

- ^ Memoranda from States: Kerala

- ^ "Protest against frequent strikes". The Hindu. The Hindu. 5 July 2005. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- ^ "Kerala's GDP hits an all-time high". Press Trust of India. Press Trust of India. 2006-02-09. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ^ a b c Mohindra KS (2003). "A report on women Self-Help Groups (SHGs) in Kerala state, India: a public health perspective". Université de Montréal Département de médecine sociale et prévention.

- ^ a b Government of Kerala 2004, p. 2.

- ^ High growth in enterprises in Kerala

- ^ Raman N (2005-05-17). "How almost everyone in Kerala learned to read". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ^ a b c Varma MS (2005-04-04). "Nap on HDI scores may land Kerala in an equilibrium trap". The Financial Express. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ a b c d Tharamangalam J (2005). "The Perils of Social Development without Economic Growth: The Development Debacle of Kerala, India" (PDF). Political Economy for Environmental Planners. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ a b Government of Kerala 2004c, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Government of Kerala 2005c.

- ^ a b Balachandran PG (2004). "Constraints on Diffusion and Adoption of Agro-mechanical Technology in Rice Cultivation in Kerala" (PDF). Centre for Development Studies. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ a b Joy CV (2004). "Small Coffee Growers of Sulthan Bathery, Wayanad" (PDF). Centre for Development Studies. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ "State/Union Territory-Wise Number of Branches of Scheduled Commercial Banks and Average Population Per Bank Branch" (PDF). Reserve Bank of India. 2002. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kumar KG (2007-10-08). "Jobless no more?". The Hindu.

A study by K.C. Zacharia and S. Irudaya Rajan, two economists at the Centre for Development Studies (CDS), Thiruvananthapuram, unemployment in Kerala has dropped from 19.1[%] in 2003 to 9.4[%] in 2007.

- ^ Nair NG. Nair PRG, Shaji H (ed.). Measurement of Employment, Unemployment, and Underemployment (PDF). Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development. Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies. ISBN 81-87621-75-3. Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- ^ Government of Kerala 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Dhar A (2006-01-28). "260 million Indians still below poverty line". The Hindu. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Government of Kerala 2006, p. 1.

- ^ (Foundation For Humanization 2002).

- ^ Kumar KG (2003-09-22). "Accidentally notorious". The Hindu Business Line. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kumar VS (2006-01-20). "Kerala State transport project second phase to be launched next month". The Hindu Business Line. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kumar VS (2003). "Institutional Strengthening Action Plan (ISAP)". Public Works Department. Government of Kerala. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ "The three airports in Kerala can be in business without affecting each other". Rediff. 1999-12-06. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Office of the Registrar General 2001b.

- ^ Kalathil MJ (2004). Nair PRG, Shaji H (ed.). Withering Valli: Alienation, Degradation, and Enslavement of Tribal Women in Attappady (pdf). Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development. Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies. ISBN 81-87621-69-9. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ^ Office of the Registrar General 2001.

- ^ Government of Kerala 2004c, p. 26.

- ^ Government of Kerala 2004c, p. 27.

- ^ Venkitakrishnan U (2003). Nair PRG, Shaji H (ed.). Rape Victims in Kerala (PDF). Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development. Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Office of the Registrar General 2004.

- ^ Heller P (4 May 2003). "Social capital as a product of class mobilization and state intervention: Industrial workers in Kerala, India". University of California: 49–50. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Lindberg A (2004). "Modernization and Effeminization in India: Kerala Cashew Workers since 1930" (PDF). 18th European Conference on Modern South Asian Studies (EASAS). Retrieved 2008-12-28.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Government of Kerala 2004r, p. 366

- ^ Government of Kerala 2002b.

- ^ a b "Kerala: Human Development Fact Sheet". United Nations Development Programme. 2001: p. 1.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) Cite error: The named reference "UNDP_2001" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Mohindra 2003, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Deaton A (2003-08-22). "Regional poverty estimates for India, 1999-2000" (PDF): p. 6. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "EFA (Education for All) Global Monitoring Report" (PDF). UNESCO. 2003: p. 156. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kutty VR (2000). "Historical analysis of the development of health care facilities in Kerala State, India" (PDF). Health Policy and Planning. 15 (1): 103–109. doi:10.1093/heapol/15.1.103. PMID 10731241. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ Kutty VR (2004). Nair PRG, Shaji H (ed.). Why low birth weight (LBW) is still a problem in Kerala: A preliminary exploration (PDF). Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development. Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies. ISBN 81-87621-60-5. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ a b c d Unnikrishnan, E (2004). "Materia Medica of the Local Health Traditions of Payyannur" (PDF). Centre for Development Studies. Retrieved 2006-01-22..

- ^ McKibben B (2006). "Kerala, India". National Geographic Traveller. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ a b c Kutty VR (2004). Nair PRG, Shaji H (ed.). Why low birth weight (LBW) is still a problem in Kerala: A preliminary exploration (PDF). Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development. Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies. p. 6. ISBN 81-87621-60-5. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ Alagarajan M (2003). "An analysis of fertility differentials by religion in Kerala: A test of the interaction hypothesis" (PDF). Population Research and Policy Review. 22: 557. doi:10.1023/B:POPU.0000020963.63244.8c.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Krishnaswami P (2004). Neelakantan S, Nair PRG, Shaji H (ed.). Morbidity Study: Incidence, Prevalence, Consequences, and Associates (PDF). Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development. Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies. ISBN 81-87621-66-4. Retrieved 2008-12-31.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Roy MKP (2004). Water quality and health status in Kollam Municipality (PDF). ISBN 81-87621-59-5. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help); Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Kerala tops primary education index

- ^ "Technical Education in Kerala — Department of Technical education". Professional Colleges in Thiruvananthapuram. Kerala Government. Retrieved 2006-08-25.

- ^ Bhagyalekshmy 2004, pp. 6–7.

- ^ UNESCO Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity : "Kutiyattam, Sanskrit Theatre"

- ^ Bhagyalekshmy 2004d, p. 29.

- ^ Bhagyalekshmy 2004d, p. 32.

- ^ Cooper KJ (20 October 1997). "For India, No Small Thing; Native Daughter Arundhati Roy Wins Coveted Booker Prize". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ "Indian's First Novel Wins Booker Prize in Britain". The New York Times. 15 October 1997. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ "Winds, Rivers & Rain". Salon. 1997. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "General Review". Registrar of Newspapers for India. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ^ "Google Malayalam News".

- ^ Ranjith KS (2004). Nair PRG, Shaji H (ed.). Rural Libraries of Kerala (PDF). Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development. Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies. pp. 20–21. ISBN 81-87621-81-8. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ "Jimmy George". Sports Portal. Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ "India Wins World Twenty20 Thriller". The Hindu. 2007-09-25. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "It's advantage Tinu at the Mecca of cricket". The Hindu. 2002-06-13. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "India Squad Profiles: Tinu Yohannan". BBC Sport. 2002. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ "Warriors from Kerala". The Hindu. 2002-01-20. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Paradise Found: Kerala, India". Fifty places of a lifetime. National Geographic Traveler. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ "Tourism beckons". The Hindu. 2004-05-11. Retrieved 2006-08-09.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Tourist Statistics — 2005 (Provisional)" (PDF). Department of Tourism. Government of Kerala. 2005. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ Santhanam K (27 January 2002). "An ideal getaway". The Hindu Magazine. The Hindu. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ "Tourist Statistics — 2006" (PDF). Department of Tourism. Government of Kerala. 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ "The stars of Pooram show are jumbos". The Hindu. 26 May 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

References

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

External links

- Government

- Official entry portal of the Government of Kerala

- Chief Minister of Kerala

- Finance Department, Govt. of Kerala

- Department of Tourism, Government of Kerala

- Directorate of Census Operations of Kerala

- Kerala Institute of Local Administration

- Other