Passive house

The term passive house (Passivhaus in German) refers to the rigorous, voluntary, Passivhaus standard for energy efficiency in buildings. It results in ultra-low energy buildings that require little energy for space heating or cooling.[1] A similar standard, MINERGIE-P, is used in Switzerland [2]. The standard is not confined only to residential properties; several office buildings, schools, kindergartens and a supermarket have also been constructed to the standard. Passive design is not the attachment or supplement of architectural design, but an integrated design process with the architectural design.[3] Although it is mostly applied to new buildings, it has also been used for refurbishments.

There are now an estimated 15,000 passive houses around the world, the vast majority built in the past few years in German-speaking countries or Scandinavia.[4]

This section appears to contradict itself on the number of passive houses. |

Since the first Passivhaus was built in German in 1990 there are now about 20,000 Passivhaus buildings across Europe (as of January 23, 2009).[1]

History

|

|

The Passive House standard originated from a conversation in May 1988 between Professors Bo Adamson of Lund University, Sweden, and Wolfgang Feist of the Institut für Wohnen und Umwelt (Institute for Housing and the Environment [5]). Their concept was developed through a number of research projects [6], aided by financial assistance from the German state of Hesse. The eventual building of four row houses (also known as terraced houses or town homes) was designed for four private clients by architects professor Bott, Ridder and Westermeyer.

The first Passivhaus buildings were built in Darmstadt, Germany, in 1990, and occupied the following year. In September 1996 the Passivhaus-Institut was founded in Darmstadt to promote and control the standard. Since then, thousands of Passive Houses have been built, to an estimate of 15,000 currently.[4][7] most of them in Germany and Austria, with others in various countries world-wide.

After the concept had been validated at Darmstadt, with space heating 90% less than required for a standard new building of the time, the 'Economical Passive Houses Working Group' was created in 1996. This developed the planning package and initiated the production of the novel components that had been used, notably the windows and the high-efficiency ventilation systems. Meanwhile further passive houses were built in Stuttgart (1993), Naumburg, Hesse, Wiesbaden, and Cologne (1997) [8].

The products developed for the Passivhaus were further commercialised during and following the European Union sponsored CEPHEUS project, which proved the concept in 5 European countries over the winter of 2000-2001. In North America the first Passivhaus was built in Urbana, Illinois in 2003, [9] and the first to be certified was built at Waldsee, Minnesota, in 2006. [10]

Standard

While some techniques and technologies were specifically developed for the Passive House standard, others (such as superinsulation) were already in existence, and the concept of passive solar building design dates back to antiquity. There was also experience from other low-energy building standards, notably the German Niedrigenergiehaus (low-energy house) standard, as well as from buildings constructed to the demanding energy codes of Sweden and Denmark.

The Passivhaus standard for central Europe requires that the building fulfills the following requirements:[11][12]

- The building must not use more than 15 kWh/m² per year (4746 btu/ft² per year) in heating and cooling energy.

- Total energy consumption (energy for heating, hot water and electricity) must not be more than 42 kWh/m² per year [13]

- Total primary energy (source energy for electricity and etc.) consumption (primary energy for heating, hot water and electricity) must not be more than 120 kWh/m² per year (3.79 × 104 btu/ft² per year)

Recommended:

- With the building de-pressurised to 50 Pa (N/m²) below atmospheric pressure by a blower door, the building must not leak more air than 0.6 times the house volume per hour (n50 ≤ 0.6 / hour).

- Further, the specific heat load for the heating source at design temperature is recommended, but not required, to be less than 10 W/m² (3.17 btu/ft² per hour).

These standards are much higher than houses built to most normal building codes. For comparisons, see the international comparisons section below.

National partners within the 'consortium for the Promotion of European Passive Houses' are thought to have some flexibility to adapt these limits locally.[14]

Space heating requirement

By achieving the Passivhaus standards, qualified buildings are able to dispense with conventional heating systems. While this is an underlying objective of the Passivhaus standard, some type of heating will still be required and most Passivhaus buildings do include a system to provide supplemental space heating. This is normally distributed through the low-volume heat recovery ventilation system that is required to maintain air quality, rather than by a conventional hydronic or high-volume forced-air heating system, as described in the space heating section below.

Construction costs

In Passivhaus buildings, the cost savings from dispensing with the conventional heating system can be used to fund the upgrade of the building envelope and the heat recovery ventilation system. With careful design and increasing competition in the supply of the specifically designed Passivhaus building products, in Germany it is now possible to construct buildings for the same cost as those built to normal German building standards, as was done with the Passivhaus apartments at Vauban, Freiburg [15].

Evaluations have indicated that while it is technically possible, the costs of meeting the Passivhaus standard increase significantly when building in Northern Europe above 60° latitude [16] [17]. European cities at approximately 60° include Helsinki in Finland and Bergen in Norway. London is at 51°; Moscow is at 55°.

Design and construction

Achieving the major decrease in heating energy consumption required by the standard involves a shift in approach to building design and construction. Design is carried out with the aid of the 'Passivhaus Planning Package' (PHPP) [18], and uses specifically designed computer simulations.

To achieve the standards, a number of techniques and technologies are used in combination:

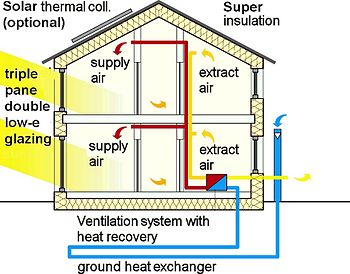

Passive solar design

Following passive solar building design techniques, where possible buildings are compact in shape to reduce their surface area, with windows oriented towards the equator (south in the northern hemisphere and north in the southern hemisphere) to maximize passive solar gain. However, the use of solar gain is secondary to minimizing the overall energy requirements.

Passive houses can be constructed from dense or lightweight materials, but some internal thermal mass is normally incorporated to reduce summer peak temperatures, maintain stable winter temperatures, and prevent possible over-heating in spring or autumn before normal solar shading becomes effective.

Superinsulation

Passivhaus buildings employ superinsulation to significantly reduce the heat transfer through the walls, roof and floor compared to conventional buildings. A wide range of thermal insulation materials can be used to provide the required high R-values (low U-values, typically in the 0.10 to 0.15 W/(m².K) range). Special attention is given to eliminating thermal bridges.

A disadvantage resulting from the thickness of wall insulation required is that, unless the external dimensions of the building can be enlarged to compensate, the internal floor area of the building may be less compared to traditional construction.

In Sweden, to achieve passive house standards, the insulation thickness would be 335 mm (about 13 in) (0.10 W/(m².K)) and the roof 500 mm (about 20 in) (U-value 0.066 W/(m².K)).

Advanced window technology

To meet the requirements of the Passivhaus standard, windows are manufactured with exceptionally high R-values (low U-values, typically 0.85 to 0.70 W/(m².K) for the entire window including the frame). These normally combine triple-pane insulated glazing (with a good solar heat-gain coefficient, low-emissivity coatings, argon or krypton gas fill, and 'warm edge' insulating glass spacers) with air-seals and specially developed thermally-broken window frames.

In Central Europe, for unobstructed south-facing Passivhaus windows, the heat gains from the sun are, on average, greater than the heat losses, even in mid-winter.

Airtightness

Building envelopes under the Passivhaus standard are required to be extremely airtight compared to conventional construction. Air barriers, careful sealing of every construction joint in the building envelope, and sealing of all service penetrations through it are all used to achieve this.

Airtightness minimizes the amount of warm (or cool) air that can pass through the structure, enabling the mechanical ventilation system to recover the heat before discharging the air externally.

Ventilation

Mechanical heat recovery ventilation systems, with a heat recovery rate of over 80% and high-efficiency electronically commutated (ECM) motors, are employed to maintain air quality, and to recover sufficient heat to dispense with a conventional central heating system. Since the building is essentially airtight, the rate of air change can be optimized and carefully controlled at about 0.4 air changes per hour. All ventilation ducts are insulated and sealed against leakage.

Although not compulsory, earth warming tubes (typically ≈200 mm (~7,9 in) diameter, ≈40 m (~130 ft) long at a depth of ≈1.5 m (~5 ft)) are often buried in the soil to act as earth-to-air heat exchangers and pre-heat (or pre-cool) the intake air for the ventilation system. In cold weather the warmed air also prevents ice formation in the heat recovery system's heat exchanger.

Alternatively, an earth to air heat exchanger, can use a liquid circuit instead of an air circuit, with a heat exchanger (battery) on the supply air. This avoids the risk of condensation, mold growth and associated health risks with the earth warming tubes.

Space heating

In addition to using passive solar gain, Passivhaus buildings make extensive use of their intrinsic heat from internal sources – such as waste heat from lighting, white goods (major appliances) and other electrical devices (but not dedicated heaters) – as well as body heat from the people and animals inside the building. (People, on average, emit heat energy equivilent to 100 Watts, see Radiation emitted by a human body).

Together with the comprehensive energy conservation measures taken, this means that a conventional central heating system is not necessary, although they are sometimes installed due to client scepticism.

Instead, Passive houses sometimes have a dual purpose 800 to 1,500 Watt heating and/or cooling element integrated with the supply air duct of the ventilation system, for use during the coldest days. It is fundamental to the design that all the heat required can be transported by the normal low air volume required for ventilation. A maximum air temperature of 50 °C (122 °F) is applied, to prevent any possible smell of scorching from dust that escapes the filters in the system.

The air-heating element can be heated by a small heat pump, by direct solar thermal energy, annualized geothermal solar, or simply by a natural gas or oil burner. In some cases a micro-heat pump is used to extract additional heat from the exhaust ventilation air, using it to heat either the incoming air or the hot water storage tank. Small wood-burning stoves can also be used to heat the water tank, although care is required to ensure that the room in which stove is located does not overheat.

Beyond the recovery of heat by the heat recovery ventilation unit, a well designed Passive house in the European climate should not need any supplemental heat source if the heating load is kept under 10W/m² [19].

Because the heating capacity and the heating energy required by a passive house both are very low, the particular energy source selected has fewer financial implications than in a traditional building, although renewable energy sources are well suited to such low loads.

Lighting and electrical appliances

To minimize the total primary energy consumption, low-energy lighting (such as compact fluorescent lamps), and high-efficiency electrical appliances are normally used.

Traits of Passive Houses

Due to their design, passive houses usually have the following traits:

- The air is fresh, and very clean. Note that for the parameters tested, and provided the filters (minimum F6) are maintained, HEPA quality air is provided. 0.3 air changes per hour (ACH) are recommended, otherwise the air can become "stale" (excess CO2, flushing of indoor air pollutants) and any greater, excessively dry (lack of humidity <40%). This implies careful selection of interior finishes and furnishings, to minimize indoor air pollution from formaldehydes, VOC's, etc. The use of a mechanical venting system also implies higher positive ion values.[citation needed] This can be counteracted somewhat via opening the window for a very brief time, plants and indoor fountains. However, it should be noted that failure to exchange air with the outside during occupied periods is not advisable.

- Because of the high resistance to heat flow (high R-value insulation), there are no "outside walls" which are colder than other walls.

- Since there are no radiators, there is more space on the rooms' walls.

- Inside temperature is homogeneous; it is impossible to have single rooms (e.g. the sleeping rooms) at a different temperature from the rest of the house. Note that the relatively high temperature of the sleeping areas is physiologically not considered desirable by some building scientists. Bedroom windows can be cracked slightly to alleviate this when necessary.

- The temperature changes only very slowly - with ventilation and heating systems switched off, a passive house typically loses less than 0.5 °C (1 °F) per day (in winter), stabilizing at around 15 °C (59 °F) in the central European climate.

- Opening windows or doors for a short time has only a very limited effect; after the windows are closed, the air very quickly returns to the "normal" temperature.

- The air inside Passive Houses, due to the lack of ventilating cold air, is much drier than in 'Standard' Houses.

International comparisons

- In the United States, a house built to the Passive House standard results in a building that requires space heating energy of 1 BTU per square foot per heating degree day, compared with about 5 to 15 BTUs per square foot per heating degree day for a similar building built to meet the 2003 Model Energy Efficiency Code. This is between 75 and 95% less energy for space heating and cooling than current new buildings that meet today's US energy efficiency codes. The Passivhaus in the German-language camp of Waldsee, Minnesota uses 85% less energy than a house built to Minnesota building codes.[20]

- In the United Kingdom, an average new house built to the Passive House standard would use 77% less energy for space heating, compared to the Building Regulations.[21]

- In Ireland, it is calculated that a typical house built to the Passive House standard instead of the 2002 Building Regulations would consume 85% less energy for space heating and cut space-heating related carbon emissions by 94%.[22]

Comparison with zero energy buildings

A net zero-energy building (ZEB) is a term for a related approach to creating buildings that use substantially less energy. A ZEB requires the use of onsite renewable energy technologies like photovoltaic rather than optimising the buildings fabric heat loss to offset the building's primary energy use.

See also

- CEPHEUS

- Energy-plus buildings

- Low-energy buildings

- List of low-energy building techniques

- Renewable heat

- Self-sufficient homes

- Thermal conductivity for an explanation of how thermal conductivity, thermal conductance, and thermal resistance are related

References

- ^ Definition of Passive House

- ^ Minergie-Standard

- ^ Yan Ji and Stellios Plainiotis (2006): Design for Sustainability. Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press. ISBN 7-112-08390-7

- ^ a b "Houses With No Furnace but Plenty of Heat". New York Times. December 26, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-27.

There are now an estimated 15,000 passive houses around the world, the vast majority built in the past few years in German-speaking countries or Scandinavia.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Institute for Housing and the Environment

- ^ Evaluation of the First Passive House

- ^ 11th International Passive House Conference 2007

- ^ European Continental Passive Houses

- ^ First US Passive House

- ^ Certified US Passive House

- ^ Passive House Requirements

- ^ Concepts and market acceptance of a cold climate Passive House

- ^ Passive Houses

- ^ europeanpassivehouses(PEP)

- ^ Cost Efficient Apartment Passive House

- ^ Passive Houses in High Latitudes

- ^ Passive Houses in Norway

- ^ Passivhaus Planning Package

- ^ Passive House Estate in Hannover-Kronsberg p72

- ^ Waldsee BioHaus design

- ^ Energy Saving Potential of Passive Houses in the UK

- ^ Passive Houses in Ireland

External links

- History of the Passivhaus

- CEPHEUS Final Report (5MB) Major European Union research project. Technical report on as-built thermal performance.