Mercury(I) chloride

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Dimercury dichloride

| |

| Other names

Mercurous chloride

Calomel | |

| Identifiers | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.030.266 |

| EC Number |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UN number | 3077 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| Hg2Cl2 | |

| Molar mass | 472.09 g/mol |

| Appearance | White solid |

| Density | 7.150 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | — |

| Boiling point | 383 °C (sublimes) |

| 0.2 mg/100 mL | |

| Hazards | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Mercury(I) fluoride Mercury(I) bromide Mercury(I) iodide |

Other cations

|

Mercury(II) chloride |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Mercury(I) chloride is the chemical compound with the formula Hg2Cl2. Also known as calomel (a mineral form, rarely found in nature) or mercurous chloride, this dense white or yellowish-white, odorless solid is the principal example of a mercury(I) compound. It is a component of reference electrodes in electrochemistry.[1][2]

History

The name calomel is thought to come from the Greek καλος beautiful, and μελας black. This name (somewhat surprising for a white compound) is probably due to its characteristic disproportionation reaction with ammonia, which gives a spectacular black coloration due to the finely dispersed metallic mercury formed. It is also referred to as the mineral horn quicksilver or horn mercury. Calomel was taken internally and used as a laxative and disinfectant, as well as in the treatment of syphilis, until the early 20th century.

Mercury became a popular remedy for a variety of physical and mental ailments during the age of "heroic medicine." It was used by doctors in America throughout the 18th century, and during the revolution, to make patients regurgitate and release their body from "impurities". Benjamin Rush, a famed physician in colonial Philadelphia and signer of the Declaration of Independence, was one particular well-known advocate of mercury in medicine and famously used calomel to treat sufferers of Yellow Fever during its outbreak in the city in 1793. Calomel was given to patients as a purgative until they began to salivate. However, it was often administered to patients in such great quantities that their hair and teeth fell out. [3]

Properties

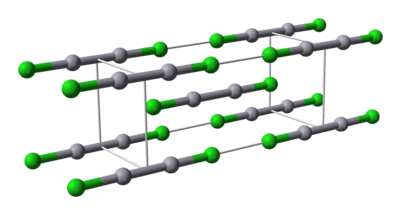

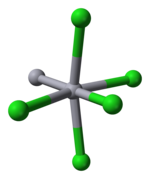

Mercury is unique among the group 12 metals for its ability to form the M-M bond so readily. Hg2Cl2 is a linear molecule. The unit cell of the crystal structure is shown below:

|

|

The Hg-Hg bond length of 253 pm (Hg-Hg in the metal is 300 pm) and the Hg-Cl bond length in the linear Hg2Cl2 unit is 243 pm.[4] The overall coordination of each Hg atom is octahedral as, in addition to the two nearest neighbours, there are four other Cl atoms at 321 pm. Longer mercury polycations exist.

Preparation and reactions

Mercurous chloride forms by the reaction of elemental mercury and mercuric chloride:

- Hg + HgCl2 → Hg2Cl2

It can be prepared via metathesis reaction involving aqueous mercury(I) nitrate using various chloride sources including NaCl or HCl.

- 2HCl + Hg2(NO3)2 → Hg2Cl2 + 2HNO3

Ammonia causes Hg2Cl2 to disproportionate:

- Hg2Cl2 + 2NH3 → Hg + Hg(NH2)Cl + NH4Cl

Calomel electrode

Mercurous chloride is employed extensively in electrochemistry, taking advantage of the ease of its oxidation and reduction reactions. The calomel electrode is a reference electrode, especially in older publications. Over the past 50 years, it has been superseded by the silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode. Although the mercury electrodes have been widely abandoned due to the dangerous nature of mercury, many chemists believe they are still more accurate and are not dangerous as long as they are handled properly. The differences in experimental potentials vary little from literature values. Other electrodes can vary by 70 to 100 millivolts.[citation needed]

Photochemistry

Mercurous chloride decomposes into mercury(II) chloride and elemental mercury upon exposure to UV light.

- Hg2Cl2 → HgCl2 + Hg

The formation of Hg can be used to calculate the number of photons in the light beam, by the technique of actinometry. By utilizing a light reaction in the presence of mercury(II) chloride and ammonium oxalate mercurous chloride is produced.

- 2HgCl2 + (NH4)2C2O4 + Light → Hg2Cl2(s) + 2[NH4+][Cl−] + 2CO2

This particular reaction was invented by J.M. Eder (hence the name Eder reaction) in 1880 and reinvestigated by W. E. Rosevaere in 1929 [5]

Related mercury(I) compounds

Mercury(I) bromide, Hg2Br2, a light yellow, whereas mercury(I) iodide, Hg2I2, is greenish in colour. Both are poorly soluble. Mercury(I) fluoride is unstable in the absence of a strong acid.

Safety considerations

Mercurous chloride is toxic, although due to its low solubility in water it is generally less dangerous than its mercuric chloride counterpart. It was used in medicine as a diuretic and purgative (laxative) in the U.S. from the early 1830s through the 1860s. Calomel was also a common ingredient in teething powders in Britain up until 1954, causing widespread mercury poisoning in the form of pink disease, which at the time had a mortality rate of 1 in 10.[6] These medicinal uses were later discontinued when the compound's toxicity was discovered.

It has also found uses in cosmetics as soaps and skin lightening creams, but these preparations are now illegal to manufacture or import in many countries including U.S., Canada, Japan and Europe. A study of workers involved in the production of these preparations showed that the sodium salt of 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulfonic acid (DMPS) was effective in lowering the body burden of mercury and in decreasing the urinary mercury concentration to normal levels.[7]

References

- ^ Housecroft, Catherine E., Sharpe, Alan G. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd edition ed.). New York: Pearson/Prentice Hall. pp. 696–697.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Skoog, Douglas A., F. James Holler and Timothy A. Nieman (1998). Principles of Instrumental Analysis (5th Edition ed.). Saunders College Pub. pp. 253–271.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Koehler, Christopher S. W. (January 2001). "Heavy Metal Medicine". Today's Chemist At Work. 10 (1): 61–65. ISSN 1062-094X. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|publication=ignored (help) - ^ Wells A.F. (1984) Structural Inorganic Chemistry 5th edition Oxford Science Publications ISBN 0-19-855370-6

- ^ W. E. Roseveare (1930). "The X-Ray Photochemical Reaction between Potassium Oxalate and Mercuric Chloride". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 52 (7): 2612–2619. doi:10.1021/ja01370a005.

- ^ Sneader (2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 45–46. ISBN 0471899801. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

{{cite book}}: Text "Walter" ignored (help) - ^ D. Gonzalez-Ramirez, M. Zuniga-Charles, A. Narro-Juarez, Y. Molina-Recio, K. M. Hurlbut, R. C. Dart and H. V. Aposhian (1998). "DMPS (2,3-Dimercaptopropane-1-sulfonate, Dimaval) Decreases the Body Burden of Mercury in Humans Exposed to Mercurous Chloride" (free full text). Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapy. 287 (1): 8–12. PMID 9765315.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)