Whaling in Japan

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2008) |

Japan has a long history of whaling. Current whaling conducted by Japan is, however, a source of political dispute between pro- and anti-whaling countries and organizations. In Taiji, Japan dead whale blubber and meat was tested and what was found was 29 times the max limit set by the Japanese Heath Ministry for Mercury.

History

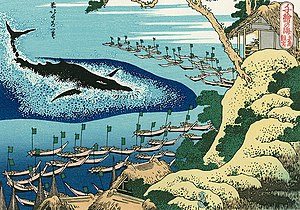

References to the consumption of whale meat date back to Kojiki, the oldest surviving book in Japan, written in the eight century[1] , which mentions whale meat being eaten by Emperor Jimmu. In Man'yōshū, the word "Whaling" (いさなとり) was frequently used in depicting the ocean or beaches.[2] Whaling is mentioned in a number of Japanese historical sources.[3] These include Whaling history (鯨史稿), Seijun Otsuki, 1808[4]; Whaling Picture Scroll (鯨絵巻), Jinemon Ikushima, 1665[5]; Whale Hunt Picture Scroll (捕鯨絵巻), Eikin Hangaya, 1666[6]; and Ogawajima Keigei Wars (小川島鯨鯢合戦), Unknown, 1667[7]. It is impossible to know whether these historic documents refer to the great whales or to some other species of small cetacean; nor does the scant evidence afford an opportunity to assess whether the whale hunts were opportunistic, subsistence, or commercial.

As early as the 13th century, records relating to Japanese whaling addressed ethical as well as practical issues. For example, at the Koganji temple in Nagato, Yamaguchi on southern Honshu island, a scroll preserves a story concerning Shinran Shonin, the founder of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism in Japan: "He was in a fishing village in 1207. A fisherman and his wife approached him and told of their worries, saying 'We live on catching fish and eating them and selling them. Would we go to hell after we die?' And Shonin said, 'If you thank them and give proper service to them, praying for the resting in peace of those fish, then there will be no problem at all.'"[8]

Organized open-boat shore whaling in Japan began in the 1570s; and continued into the early 20th century.[9] They first only used hand-harpoons and lances, but by the 1670s they employed nets as well. They targeted right and humpback whales, but also took blue, fin, sei/bryde's, and gray whales.[citation needed]

Japanese traditional whaling technique was dramatically developed in the 17th century in Taiji, Wakayama.[10] [11] Wada Chubei organized the group hunting system (刺手組) and introduced new handheld harpoon in 1606. Wada Kakuemon, later known as Taiji Kakuemon, invented the whaling net technique called Amitori hou (網取法) and increased the safety and efficiency of whaling.

Whales have long been a source of food, oil, and crafts' material. A famous proverb quotes: "There's nothing to throw away from a whale except its voice."

One of the purposes of US naval officer Matthew Perry expedition to Japan in 1853 was to obtain a base for whaling in the north-west Pacific Ocean.

When Norwegian-style modern whaling, based on the use of power-driven vessels and whaling guns, was introduced in the Meiji era, most Japanese fishermen were opposed to the indiscriminate killing of whales, which they regarded as deities of the sea and which helped to corral fish.[citation needed] In the early 1900s, Japanese whaling techniques developed further and Japanese whalers began turning to the West for modern whaling techniques.[citation needed]

Following the devastation of World War II, food was scarce, consequently whales, being a cheap source of protein, became a larger part of the Japanese post-war diet.[citation needed]

In 1982, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) voted on a moratorium on commercial whaling to go into force in 1986. While Japan initially intended to oppose the moratorium, the United States pressured them to comply in turn for continued rights to fish in Alaskan waters. After the US went ahead anyway with excluding all foreign vessels from fishing in US waters, Japan began its research programme in order to one day restart commercial whaling under IWC regulation.[12]

Japan's whale consumption peaked in 1962 at 226,000 tons, then declined steadily until it fell to 15,000 tons in 1985, the year before the commercial whaling ban.[13] Japan has maintained its interest in the resumption of commercial whaling, but has not succeeded in persuading the IWC to lift the ban.

Scientific research

After halting its commercial whaling, Japan began scientific research hunts to provide a basis for the resumption of sustainable whaling.[14] The number of whales caught under the project is considerably lower than the number caught under the commercial catch. The IWC Scientific Committee collects up to date data on catch limits and catches taken since 1985. Numbers have ranged from less than 200 in 1985 to close to 1,000 in 2007.[15] [16] [17]

The research is conducted by the Institute of Cetacean Research (ICR), a privately-owned, non-profit institution. The institute receives its funding from government subsidies and Kyodo Senpaku, which handles processing and marketing of byproducts such as whale meat. Japan carries out its research in two areas: the North-West Pacific Ocean (JARPN II) and the Antarctic Ocean (JARPA) Southern Hemisphere catch. The 2007/08 JARPA mission had a quota of 900 minke whales and 50 fin whales.[18]

Major discoveries claimed by JARPA 1 include: finding the population structure of minke whales in the Antarctic is healthy; detecting change in the ecosystem of the Antarctic Ocean; finding "very low level" of contaminants in minke whales.[19]

As consumption of fish in Japan has shrunk, Japanese fisheries companies have expanded abroad and started facing pressure from partners and environmental groups. Five large fishing companies transferred their whaling fleet shares to public interest corporations in 2006.[20] In 2007, Kokuyo and Maruha, two of Japan's four largest fishing companies, decided to end their sales of whale meat due to pressure from partners and environmental groups in the US.[21][22]

Debate in the IWC

The most vocal opponents of the Japanese push for a resumption of commercial whaling are Australia, New Zealand,and the United Kingdom, whose stated purpose for opposing whaling is the need for conservation of endangered species.[citation needed]

In July 2004 it was reported[23] that a working group of the Japan's ruling Liberal Democratic had drawn up plans to leave the IWC in order to join a new pro-whaling organization, NAMMCO, because of the IWC's refusal to back the principle of sustainable commercial whaling. Japan is particularly opposed to the IWC Conservation Committee, introduced in 2003, which it says exists solely to prevent any whaling. Any directives from the IWC are undertaken on a purely voluntary basis as state sovereignty means that there are few avenues by which international law can be enforced.

At an IWC meeting in 2006, a resolution calling for the eventual return of commercial whaling was passed by a majority of just one vote. There has been a failure to lift the ban on commercial whale hunting and Japan has since threatened to pull out of the International Whaling Commission (IWC).[24]

In 2007 the IWC passed a resolution asking Japan to refrain from issuing a permit for lethal research in the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary - the main Japanese whaling area.[25]

After a visit to Tokyo by the chairman of the IWC, asking the Japanese for their co-operation in sorting out the differences between pro- and anti-whaling nations on the Commission, the Japanese whaling fleet agreed that no humpback whales would be caught for the two years it would take for the IWC to reach a formal agreement.[26]

Controversy

Anti-whaling governments and groups have strongly opposed Japan's research program. Greenpeace argues that whales are endangered and must be protected. [27] The Japanese government maintains that certain populations are strong enough to sustain a managed hunt. The 1985 IWC estimate for put the Southern Hemisphere Minke whale population at 761,000 (510,000 - 1,140,000 in the 95% confidence estimate).[28] A paper submitted to the IWC on population estimates in Antarctic waters using CNB gives a population of 665,074 based on Southern Ocean Whale and Ecosystem Research Programme (SOWER) data.[29]

Research methodology has come under scrutiny as it has been argued that non-lethal methods of research are available[30] and that Japan's research whaling is commercial whaling in disguise.[31] The Japanese claim that the accuracy of tissue and feces samples is insufficient and lethal sampling is necessary.[32]

A 2006 episode of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's popular science show Catalyst, which strongly argued against whaling, reported that of the 18 year JARPA I program, which lethally obtained samples from 6800 whales, less than 55 peer-reviewed papers were produced, of which only 14 were claimed on the program to be relevant to the goals of the JARPA program, and that only four would require lethal sampling. Some of the research includes a paper named Fertilizability of ovine, bovine, and minke whales spermatazoa intracytoplasmically injected into bovine oocytes.[33] Joji Morishita of JARPA has said the number of samples was required in order to obtain statistically significant data. More detailed list of Scientific papers presented to IWC up to 2005.[4]

Sea Shepherd contests that Japan, as well as Iceland and Norway, is in violation of the IWC moratorium on all commercial whaling.[34] This argument rests on their belief that Japan's research program is actually a commercial program in disguise. Japan categorically denies this allegation, stating that their primary goal is the sustainable use of all marine resources and that the lethal methods used are permitted under article VIII of the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. [35]

Disputes

Due to the proximity to Australia and a prevelant anti-whaling sentiment in the country[citation needed] the government of Australia has been particularly vocal in its opposition to Japan's whaling activity in the Southern Pacific. In 1994, Australia claimed a 200-nautical-mile (370 km) exclusive economic zone (EEZ) around the Australian Antarctic Territory, which also includes a southerly portion of the IWC Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary. However, Antarctic territorial claims are not recognized by most countries, including Japan.[citation needed]

The Australian Rudd government's stance on Japanese whaling has attracted very strong public support in Australia.[citation needed] Japanese whaling is seen as a serious threat to Australian whale tourism, having only become viable as a result of the replenishment of global whale stocks.[citation needed] In December 2007, the Rudd government announced plans to monitor Japanese whalers about to enter Australian waters in order to gather evidence against Japanese whalers for a possible international legal challenge[36][37][38][39] and on January 8, 2008 the Australian government sent the Australian customs vessel Oceanic Viking to track and monitor the fleet.[40]

The Japanese whaling fleet had several clashes with activists from the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society attempting disrupt its mission in the summers of 2007-2008 and 2008-2009. On January 15, 2008 two activists members travelling on the MV Steve Irwin boarded the whaling ship Yushin Maru 2 without permission and were subsequently detained onboard the ship for a number of days. Japan claimed that four crew members on board a Japanese whaling ship in Antarctic waters were injured March 3, 2008 when the anti-whaling group threw butyric acid on board.[41] Japan confirmed the later throwing of "Flashbang" grenades onto the Sea Shepherd ship, MV Steve Irwin by their whaling ship, Nisshin Maru. Japan also confirmed firing a "warning shot" into the air. The captain of the Steve Irwin, Paul Watson claimed that he was hit by a bullet that the Japanese had fired.[42] On February 7, 2009 the MV Steve Irwin clashed with two Japanese vessels as it was attempting to transfer a whale. Both sides claimed the other had been at fault.[43][44][45]

On March 6, 2008 members of the International Whaling Commission met in London to discuss reaching an agreement on whale conservation rules.[46] Japanese whalers and anti-whaling activists clashed in the waters near Antarctica on March 7, 2008, with each side offering conflicting accounts of the confrontation.[47] The IWC called upon the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society to refrain from dangerous actions and reiterated its condemnation of any actions that are a risk to human life and property in relation to the activities of vessels at sea.[48]

On March 8, 2008, Solomon Islands' Prime Minister Derek Sikua said that Japan had offered to pay for the country's delegates to attend the March 6, 2008 IWC meeting in London. Hideki Moronuki, the whaling chief at Japan's Fisheries Agency, denied the allegation saying, "There is no truth to it." He further stated that "Sikua may have confused the London meet with a seminar last week in Tokyo to which Japan invited delegates from 12 developing nations that have recently joined or are considering joining the IWC. Japan sometimes holds small seminars on whaling and invites delegates from countries. I wonder if Mr Sikua mixed up such seminars and IWC meetings,"[49]

Public support for whaling

Although anti-whaling campaigners try to convince people outside Japan that the Japanese public don't support the government for its whaling policy[50][51], the polls conducted by the Nikkei and Japan's Cabinet Office show that the Japanese public overwhelmingly support whaling.[52] All the major political parties from the ruling LDP to the Japanese Communist Party do support whaling.[53][54]

References

- ^ Kojiki: [1] Chamberlain, Basil Hall. (2005). The Kojiki, p.169; Kimura, Tets. "Getting to know the Japanese," The Age (Melbourne). January 16, 2007.

- ^ Man'yōshū: [2]

- ^ 九州大学総合研究博物館, 鯨絵・捕鯨史料

- ^ 九州大学総合研究博物館, 鯨史稿 巻之六

- ^ 九州大学総合研究博物館, 鯨絵巻 上

- ^ 九州大学総合研究博物館, 捕鯨絵巻

- ^ 九州大学総合研究博物館, 小川島鯨鯢合戦

- ^ Black, Richard (May 23, 2007). "Temples of the whale". BBC.

- ^ Kasuya (2002). Encycopedia of Marine Mammals.

- ^ "Whale fishing in Hizen-no-kuni (九州大学総合研究博物館)". National Archives of Japan.

- ^ "鯨史稿 巻之六 (Japanese Whaling, group hunting system)".

- ^ Black, Richard (May 16, 2007). "Did Greens help kill the whale?". BBC News. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Whaling: A Japanese Obsession With American Roots - New York Times

- ^ Japan's research whaling in the Antarctic (PDF), retrieved 2008-02-04

{{citation}}:|first=missing|last=(help); External link in|author-link= - ^ "Catch Limits & Catches taken; Information on recent catches taken by commercial, aboriginal and scientific permit whaling". International Whaling Commission. 2007-07-10. Retrieved 2008-02-07.

- ^ "Catches under Objection since 1985". International Whaling Commission. 2007-09-20. Retrieved 2008-02-07.

- ^ "Special Permit catches since 1985". International Whaling Commission. 2007-09-20. Retrieved 2008-02-07.

- ^ Institute of Cetacean Research

- ^ Edited by the Fisheries Agency. "Current Findings of the Japanese Whale Research Program under the Special Permit in the Antarctic". The Riches of the Sea. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Hogg, Chris (April 4, 2006). "'Victory' over Japanese whalers". BBC News. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Biggs, Stuart (2007-05-30). "Kyokuyo Joins Maruha to End Whale Meat Sales in Japan". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ^ "Kyoko America Corporation" (Press release). Kyoko America Corporation. 2007-04-16. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- ^ BBC NEWS | Science/Nature | Japan plans pro-whaling alliance

- ^ Report from News.com.au

- ^ International Whaling Commission, Resolution 2007-1: "Resolution on JARPA" [3]

- ^ BBC NEWS | World | Asia-Pacific | Japan changes track on whaling

- ^ Whaling, Greenpeace, retrieved 2008-02-04

- ^ The Environment; Its effects on global whale abundance, International Whaling Commission, 2006-07-26, retrieved 2008-02-04

- ^ , IWC, pp. 12 (section *8) http://www.iwcoffice.org/_documents/sci_com/SC60docs/DocList-23-05.pdf, retrieved 2009-01-31

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ BBC News: US joins criticism of whaling

- ^ Times (UK): Australia condemns whale kill

- ^ Under the skin of whaling science, BBC, retrieved 2007-05-25

- ^ Catalyst: Whale Science, 8 June 2006. ABC. Reporter/Producer: Dr Jonica Newby. (Transcript and full program available online)

- ^ The Whale's Navy, Sea Shepherd, retrieved 2008-02-04

- ^ The Position of the Japanese Government on Research Whaling, The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, retrieved 2008-02-04

- ^ Navy, RAAF to shadow whalers | The Daily Telegraph

- ^ "Customs ship to shadow Japanese whalers". ABC News. 2007-12-19. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ^ "Australia sends patrols to shadow Japan whalers". National Post. 2007-12-19. Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ^ "Spy v spy as Airbus joins the fight against whaling". Sydney Morning Herald. 2008-01-22. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ^ "Greenpeace applauds departure of Oceanic Viking (2008)". livenews.com.au. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ "Japan: Whaling ship attacked with acid". CNN. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ^ "Sea Shepherd captain 'shot by Japanese whalers'". ABC News (Australia). Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ^ http://www.icrwhale.org/pdf/090206-3Release.pdf

- ^ http://www.icrwhale.org/eng/090206SS2.wmv

- ^ "Activist ship and whalers collide". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ^ "Japan to lobby whaling commission to support hunts". CNN. Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ^ "Whalers, activists clash in Antarctica". CNN. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ^ "STATEMENT ON SAFETY AT SEA". IWC. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ^ , AFP http://afp.google.com/article/ALeqM5gETk0rJzQZ9zMND1Dg58gAc1XKxQ

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ GreenpeaceVideo (2007), We love Japan, video retrieved 23 February, 2009.

- ^ Sakuma, Junko (2006), Investigating the sale of whale meat - the "byproduct" of research whaling, article retrieved 23 February, 2009.

- ^ The Institute of Cetacean research (2007), Yahoo poll shows more support for whaling in Japan, article retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ^ The Asahi (July 5 2008), 捕鯨文化守れ 地方議会も国会も超党派で一致団結 article retrieved 23 February, 2009.

- ^ Kujira Topics (2002), ガンバレ日本! 捕鯨再開。 article retrieved 23 February, 2009.

See also

- Whaling

- Whaling in Australia

- Whaling in Western Australia

- Fishery

- Whale watching

- Cuisine of Japan

- Convention of Kanagawa

- International Whaling Commission

- Nisshin Maru

- Oriental Bluebird

- Greenpeace

- Sea Shepherd

- Dolphin drive hunting

- Taiji, Wakayama

External links

Official bodies

- Whaling Section of Japan

- The Institute of Cetacean Research

- The International Whaling Commission

- National Archives of Japan: "Whale fishing in Hizen-no-kuni"

Organisations

Reportage

- Catalyst: Whale Science. From the ABC1 Catalyst.

Multimedia