Osgood–Schlatter disease

| Osgood–Schlatter disease | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Rheumatology, orthopedic surgery |

Osgood-Schlatter disease or syndrome(N)(also known as tibial tubercle apophyseal traction injury) is an inflammation of the growth plate at the tibial tuberosity, and is one of a group of conditions collectively called osteochondroses. The condition is named after the American surgeon Robert Bayley Osgood (1873–1956) and the Swiss surgeon Carl Schlatter (1864–1934), who independently described the disease in 1903.[1][2][3]

The condition occurs in active boys and girls aged 11-15[4], coinciding with periods of growth spurts. It occurs more frequently in boys than in girls, with reports of a male-to-female ratio ranging from 3:1 to as high as 7:1. It has been suggested the difference is related to a greater participation by boys in sports and risk activities than by girls.

The condition is usually self-limiting and is caused by stress on the patellar tendon that attaches the quadriceps muscle at the front of the thigh to the tibial tuberosity. Following an adolescent growth spurt, repeated stress from contraction of the quadriceps is transmitted through the patellar tendon to the immature tibial tuberosity. This can cause multiple subacute avulsion fractures along with inflammation of the tendon, leading to excess bone growth in the tuberosity and producing a visible lump.

The syndrome may develop without trauma or other apparent cause. But some studies report up to 50% of patients give a history of precipitating trauma.

In a retrospective study of adolescents, young athletes actively participating in sports showed a frequency of 21% reporting the syndrome compared with only 4.5% of age-matched nonathletic controls.[5]

Sinding–Larsen–Johansson Syndrome is an analogous condition involving the patellar tendon and the lower margin of the patella bone, instead of the upper margin of the tibia.

Symptoms

- Knee pain is usually the presenting symptom that occurs during activities such as running, jumping, squatting, and ascending or descending stairs. The pain can be reproduced by extending the knee against resistance, stressing the quadriceps, or squatting with the knee in full flexion. Pain is mild and intermittent initially. In acute phase the pain is severe and continuous in nature. Impact of the affected area which can very painful

- Bilateral symptoms are observed in 20–30% of patients.

- The symptoms usually resolve with treatment but may recur as a new episode until skeletal maturity, when the tibial epiphysis fuses. Symptoms, however, may continue to wax and wane for 12–24 months before complete resolution. In approximately 10% of patients the symptoms continue unabated into adulthood, despite all conservative measures.WHEN YOU GET HIT IN THE SPOT IT HURTS ALOT[6]

Osgood Shlatter happens mostly to boys who are having a growth spurt in their early teen years. It causes pain, swelling and tenderness below the knee (or both knees) and over the shin bone. It results from the pull of the quadriceps due to the growth spurt. Kids notice the pain when they are running, jumping or walking up stairs. It is common in sports like football, soccer, basketball and even in ballet and gymnastics. [7]

Treatment

Diagnosis is made clinically,[8] and treatment is conservative with rest and simple pain reduction measures of ice packs and if required paracetamol (acetaminophen) or ibuprofen. The condition usually resolves in a few months, with a study of young athletes revealing a requirement of complete training cessation for 3 months (on average) and gradual resumption of full training by 7 months.[5]

Bracing or use of plaster of paris to enforce joint immobilization is rarely required and does not necessarily give quicker resolution.[9] Surgical excision may rarely be required in skeletally mature patients.[6]

Typically, this disease goes away with time. Sometimes it might take a few months, but very rarely does it stick. If you ignore rest, the disease could get worse and take longer to treat. When you stop growing, your patellar tendons get a lot stronger. [10]

After symptoms have resolved, a gradual progression to the desired activity level may begin. In addition, predisposing factors should be evaluated and addressed. Commonly quadriceps and/or hamstring tightness is present and should be addressed with stretching exercises. Training factors such as intensity and repetition should also be evaluated and addressed.

What to do next

If you are experience knee pain definitely go see a doctor. If you do have Osgood Shlatter Disease, the doctor will most likely ask you to take it easy on sports for awhile. That doesn't mean you have to give up sports, but limit the amount of time you spend playing them. You will have to wait until the knee pain is gone for at least two to three months. If pain does start to bother you, make sure to use the "RICE" technique: Rest the knee, Ice the knee for 20 minutes - three times a day, Compress the knee with an elastic bandage, Elevate the leg. [11]

Additional images

-

X-ray showing Osgood-Schlatter disease (arrow).

-

MBq Osgood-Schlatter

-

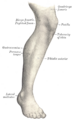

Lateral aspect of right leg. (Tuberosity of tibia labeled at center right.)

HERRO

References

- ^ Osgood R.B. (1903). "Lesions of the tibia tubercle occurring during adolescence". Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. 148: 114–7.

- ^ Schlatter C. (1903). "Verletzungen des schnabelförmigen Forsatzes der oberen Tibiaepiphyse". [Bruns] Beiträge zur klinischen Chirurgie. 38: 874–87.

- ^ Nowinski RJ, Mehlman CT (1998). "Hyphenated history: Osgood-Schlatter disease". Am J. Orthop. 27 (8): 584–5. PMID 9732084.

- ^ Yashar A, Loder RT, Hensinger RN (1995). "Determination of skeletal age in children with Osgood-Schlatter disease by using radiographs of the knee". J Pediatr Orthop. 15 (3): 298–301. PMID 7790482.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kujala UM, Kvist M, Heinonen O (1985). "Osgood-Schlatter's disease in adolescent athletes. Retrospective study of incidence and duration". Am J Sports Med. 13 (4): 236–41. doi:10.1177/036354658501300404. PMID 4025675.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Gholve PA, Scher DM, Khakharia S, Widmann RF, Green DW (2007). "Osgood Schlatter syndrome". Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 19 (1): 44–50. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e328013dbea. PMID 17224661.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Overcoming Osgood Schlatter Disease" Kidzworld.com. Retrieved on 2009-03-27.

- ^ Cassas KJ, Cassettari-Wayhs A (2006). "Childhood and adolescent sports-related overuse injuries". Am Fam Physician. 73 (6): 1014–22. PMID 16570735.

- ^ Engel A, Windhager R (1987). "[Importance of the ossicle and therapy of Osgood-Schlatter disease]". Sportverletz Sportschaden (in German). 1 (2): 100–8. doi:10.1055/s-2007-993701. PMID 3508010.

- ^ "Overcoming Osgood Schlatter Disease" Kidzworld.com. Retrieved on 2009-03-27.

- ^ "Overcoming Osgood Schlatter Disease" Kidzworld.com. Retrieved on 2009-03-27.