Externality

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2007) |

In economics, an externality or spillover of an economic transaction is an impact on a party that is not directly involved in the transaction. In such a case, prices do not reflect the full costs or benefits in production or consumption of a product or service. A positive impact is called an external benefit, while a negative impact is called an external cost. Producers and consumers in a market may either not bear all of the costs or not reap all of the benefits of the economic activity. For example, manufacturing that causes air pollution imposes costs on the whole society, while fire-proofing a home improves the fire safety of neighbors.

In a competitive market, the existence of externalities would cause either too much or too little of the good to be produced or consumed in terms of overall costs and benefits to society. If there exist external costs such as pollution, the good will be overproduced by a competitive market, as the producer does not take into account the external costs when producing the good. If there are external benefits, such as in areas of education or public safety, too little of the good would be produced by private markets as producers and buyers do not take into account the external benefits to others. Here, overall cost and benefit to society is defined as the sum of the economic benefits and costs for all parties involved.

Implications

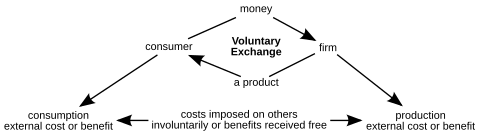

Standard economic theory states that any voluntary exchange is mutually beneficial to both parties involved in the trade. This is because if either the buyer or the seller would not benefit from the trade, they would refuse it. However, an exchange can cause additional effects on third parties. From the perspective of those affected, these effects may be negative (pollution from a factory), or positive (honey bees that pollinate the garden). Welfare economics has shown that the existence of externalities result in outcomes that are not socially optimal. Those who suffer from external costs do so involuntarily, while those who enjoy external benefits do so at no cost.

A voluntary exchange may reduce societal welfare if external costs exist. The person who is affected by the negative externality in the case of air pollution will see it as lowered utility: either subjective displeasure or potentially explicit costs, such as higher medical expenses. The externality may even be seen as a trespass on their lungs, violating their property rights. Thus, an external cost may pose an ethical or political problem. Alternatively, it might be seen as a case of poorly-defined property rights, as with, for example, pollution of bodies of water that may belong to no-one (either figuratively, in the case of publicly-owned, or literally, in some countries and/or legal traditions).

On the other hand, an external benefit would increase the utility of third parties at no cost to them. Since collective societal welfare is improved, but the providers have no way of monetizing the benefit, less of the good will be produced than would be optimal for society as a whole. Goods with positive externalities include education (believed to increase societal productivity and well-being; but controversial, as these benefits may be internalized), health care (which may reduce the health risks and costs for third parties for such things as transmittable diseases) and law enforcement. Positive externalities are often associated with the free rider problem. For example, individuals who are vaccinated reduce the risk of contracting the relevant disease for all others around them, and at high levels of vaccination, society may receive large health and welfare benefits; but any one individual can refuse vaccination, still avoiding the disease by "free riding" on the costs borne by others.

There are a number of potential means of improving overall social utility when externalities are involved. The market-driven approach to correcting externalities is to "internalize" third party costs and benefits, for example, by requiring a polluter to repair any damage caused. But, in many cases internalizing costs or benefits is not feasible, especially if the true monetary values cannot be determined.

The monetary values of externalities are difficult to quantify, as they may reflect the ethical views and preferences of the entire population. It may not be clear whose preferences are most important, interests may conflict, the value of externalities may be difficult to determine, and all parties involved may try to influence the policy responses to their own benefit. An example is the externalities of the smoking of tobacco, which can cost or benefit society depending on the situation. Because it may not be feasible to monetize the costs and benefits, another method is needed to either impose solutions or aggregate the choices of society, when externalities are significant. This may be through some form of representative democracy or other means. Political economy is, in broad terms, the study of the means and results of aggregating those choices and benefits that are not limited to purely private transactions.

Laissez-faire economists such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman sometimes refer to externalities as "neighborhood effects" or "spillovers", although externalities are not necessarily minor or localized.

Examples

Negative

Many negative externalities (also called "external costs" or "external diseconomies") are related to the environmental consequences of production and use. The article on environmental economics also addresses externalities and how they may be addressed in the context of environmental issues.

- Systemic risk describes the risks to the overall economy arising from the risks which the banking system takes. That the private costs of banking failure may be smaller than the social costs justifies banking regulations, although regulations could create a moral hazard.[1]

- Anthropogenic climate change is attributed to greenhouse gas emissions from burning oil, gas, and coal. Global warming has been ranked as the #1 externality of all economic activity, in the magnitude of potential harms and yet remains unmitigated.[citation needed]

- Water pollution by industries that adds poisons to the water, which harm plants, animals, and humans.

- Industrial farm animal production, on the rise in the 20th century, resulted in farms that were easier to run, with fewer and often less-highly-skilled employees, and a greater output of uniform animal products. However, the externalities with these farms include "contributing to the increase in the pool of antibiotic-resistant bacteria because of the overuse of antibiotics; air quality problems; the contamination of rivers, streams, and coastal waters with concentrated animal waste; animal welfare problems, mainly as a result of the extremely close quarters in which the animals are housed." [2][3]

- The harvesting by one fishing company in the ocean depletes the stock of available fish for the other companies and overfishing may be the result. This is an example of a common property resource, sometimes referred to as the Tragedy of the commons.

- When car owners use roads, they impose congestion costs on all other users.

- A business may purposely underfund one part of their business, such as their pension funds, in order to push the costs onto someone else, creating an externality. Here, the "cost" is that of providing minimum social welfare or retirement income; economists more frequently attribute this problem to the category of moral hazards.

- Consumption by one consumer causes prices to rise and therefore makes other consumers worse off, perhaps by reducing their consumption. These effects are sometimes called "pecuniary externalities". Many economists do not accept the concept of pecuniary externalities, attributing such problems to anti-competitive behavior, monopoly power, or other definitions of market failures.

- The consumption of alcohol by bar-goers in some cases leads to drinking and driving accidents which injure or kill pedestrians and other drivers.

- Commonized costs of declining health and vitality caused by smoking and/or alcohol abuse. Here, the "cost" is that of providing minimum social welfare. Economists more frequently attribute this problem to the category of moral hazards, the prospect that a party insulated from risk may behave differently from the way they would if they were fully exposed to the risk. For example, an individual with insurance against automobile theft may be less vigilant about locking his car, because the negative consequences of automobile theft are (partially) borne by the insurance company.

- The cost of storing nuclear waste from nuclear plants for more than 1,000 years (over 100,000 for some types of nuclear waste) is not included in the cost of the electricity the plant produces. The third party here is the next several hundred generations.

- The cost of removing the Space debris from Earth orbit is not payed bay the party that sent the rockets and satellites in orbit. It is proven that soon the Earth Orbit will be clogged with space debris traveling with big speed thus making Space Exploration impossible.

In these situations the marginal social benefit of consumption is less than the marginal private benefit of consumption. (i.e. SMB < PMB) This leads to the good or service being over-consumed relative to the social optimum. Without intervention the good or service will be under-priced and the negative externalities will not be taken into account.

Positive

Examples of positive externalities (beneficial externality, external benefit, external economy, or Merit goods) include:

- A beekeeper keeps the bees for their honey. A side effect or externality associated with his activity is the pollination of surrounding crops by the bees. The value generated by the pollination may be more important than the value of the harvested honey.

- An individual planting an attractive garden in front of his house may provide benefits to others living in the area, and even financial benefits in the form of increased property values for all property owners.

- An individual buying a product that is interconnected in a network (e.g., a video cellphone) will increase the usefulness of such phones to other people who have a video cellphone. When each new user of a product increases the value of the same product owned by others, the phenomenon is called a network externality or a network effect. Network externalities often have "tipping points" where, suddenly, the product reaches general acceptance and near-universal usage, a phenomenon which can be seen in the near universal take-up of cellphones in some Scandinavian countries.

- Knowledge spillover of inventions and information - once an invention (or most other forms of practical information) is discovered or made more easily accessible, others benefit by exploiting the invention or information. Copyright and intellectual property law are mechanisms to allow the inventor or creator to benefit from a temporary, state-protected monopoly in return for "sharing" the information through publication or other means.

- Sometimes the better part of a benefit from a good comes from having the option to buy something rather than actually having to buy it. A private fire department that only charged people that had a fire, would arguably provide a positive externality at the expense of an unlucky few. Some form of insurance could be a solution in such cases, as long as people can accurately evaluate the benefit they have from the option.

- A family member buying a movie or game will provide a positive externality to the rest of the family, who then can watch the movie or play the game.

- An organization that purchases a large screen and projector will give benefits to those who may use the screen for various purposes.

- Home ownership creates a positive externality in that homeowners are more likely than renters to become actively involved in the local community. For this reason, in the US interest paid on a home mortgage is an available deduction from the income tax. [4]

- Education creates a positive externality because more educated people are less likely to engage in violent crime, which makes everyone in the community, even people who are not well educated, better off.

As noted, externalities (or proposed solutions to externalities) may also imply political conflicts, rancorous lawsuits, and the like. This may make the problem of externalities too complex for the concept of Pareto optimality to handle. Similarly, if too many positive externalities fall outside the participants in a transaction, there will be too little incentive on parties to participate in activities that lead to the positive externalities.

Positional

Positional externalities refer to a special type of externality that depends on the relative rankings of actors in a situation. Because every actor is attempting to "one up" other actors, the consequences are unintended and economically inefficient.

One example is the phenomenon of "overeducation" (referring to post-secondary education) in the North American labour market. In the 1960s, many young middle-class North Americans prepared for their careers by completing a bachelor's degree. However, by the 1990s, many people from the same social milieu were completing master's degrees, hoping to "one up" the other competitors in the job market by signalling their higher quality as potential employees. By the 2000s, some jobs which had previously only demanded bachelor's degrees, such as policy analysis posts, were requiring master's degrees. Some economists argue that this increase in educational requirements was above that which was efficient, and that it was a misuse of the societal and personal resources that go into the completion of these master's degrees.

Another example is the buying of jewelry as a gift for another person, e.g. a spouse. For Husband A to show that he values Wife A more than Husband B values Wife B, Husband A must buy more expensive jewelry than Husband B. As in the first example, the cycle continues to get worse, because every actor positions him or herself in relation to the other actors. This is sometimes called Keeping up with the Joneses.

One solution to such externalities is regulations imposed by an outside authority. For the first example, the government might pass a law against firms requiring master's degrees unless the job actually required these advanced skills.

Supply and demand diagram

The usual economic analysis of externalities can be illustrated using a standard supply and demand diagram if the externality can be monetized and valued in terms of money. An extra supply or demand curve is added, as in the diagrams below. One of the curves is the private cost that consumers pay as individuals for additional quantities of the good, which in competitive markets, is the marginal private cost. The other curve is the true cost that society as a whole pays for production and consumption of increased production the good, or the marginal social cost.

Similarly there might be two curves for the demand or benefit of the good. The social demand curve would reflect the benefit to society as a whole, while the normal demand curve reflects the benefit to consumers as individuals and is reflected as effective demand in the market.

External costs

The graph below shows the effects of a negative externality. For example, the steel industry is assumed to be selling in a competitive market – before pollution-control laws were imposed and enforced (e.g. under laissez-faire). The marginal private cost is less than the marginal social or public cost by the amount of the external cost, i.e., the cost of air pollution and water pollution. This is represented by the vertical distance between the two supply curves. It is assumed that there are no external benefits, so that social benefit equals individual benefit.

If the consumers only take into account their own private cost, they will end up at price Pp and quantity Qp, instead of the more efficient price Ps and quantity Qs. These latter reflect the idea that the marginal social benefit should equal the marginal social cost, that is that production should be increased only as long as the marginal social benefit exceeds the marginal social cost. The result is that a free market is inefficient since at the quantity Qp, the social benefit is less than the social cost, so society as a whole would be better off if the goods between Qp and Qs had not been produced. The problem is that people are buying and consuming too much steel.

This discussion implies that pollution is more than merely an ethical problem; it is more than just "greedy" and profit-maximizing firms. The problem is one of the disjuncture between marginal private and social costs that is not solved by the free market. There is a problem of societal communication and coordination to balance benefits and costs. This discussion also implies that pollution is not something solved by competitive markets. In fact, a monopoly might be able to use some of its excess profits to be benevolent and internalize the externality (pay the cost of the pollution). More likely, a monopoly would artificially restrict the quantity supplied in order to maximize profits. This would actually benefit society in this situation because it would mean less pollution than in the competitive case. Perfectly competitive firms have no choice but to produce according to market incentives or private costs: if one decides to internalize external costs, it implies that this producer would incur higher costs than those of its competitors and likely be forced to exit from the market. So some collective solution is needed, such as, government intervention banning or discouraging pollution, by means of economic incentives such as taxes, or an alternative economy such as participatory economics.

External benefits

The graph below shows the effects of a positive or beneficial externality. For example, the industry supplying smallpox vaccinations is assumed to be selling in a competitive market. The marginal private benefit of getting the vaccination is less than the marginal social or public benefit by the amount of the external benefit (for example, society as a whole is increasingly protected from smallpox by each vaccination, including those who refuse to participate). This marginal external benefit of getting a smallpox shot is represented by the vertical distance between the two demand curves. Assume there are no external costs, so that social cost equals individual cost.

If consumers only take into account their own private benefits from getting vaccinations, the market will end up at price Pp and quantity Qp as before, instead of the more efficient price Ps and quantity Qs. These latter again reflect the idea that the marginal social benefit should equal the marginal social cost, i.e., that production should be increased as long as the marginal social benefit exceeds the marginal social cost. The result in an unfettered market is inefficient since at the quantity Qp, the social benefit is greater than the societal cost, so society as a whole would be better off if more goods had been produced. The problem is that people are buying too few vaccinations.

The issue of external benefits is related to that of public goods, which are goods where it is difficult if not impossible to exclude people from benefits. The production of a public good has beneficial externalities for all, or almost all, of the public. As with external costs, there is a problem here of societal communication and coordination to balance benefits and costs. This also implies that vaccination is not something solved by competitive markets. The government may have to step in with a collective solution, such as subsidizing or legally requiring vaccine use. If the government does this, the good is called a merit good.

Possible solutions

There are at least four general types of solutions to the problem of externalities:

- Criminalization: As with prostitution, addictive drugs, commercial fraud, and many types of environmental and public health laws.

- Civil Tort law: For example, class action by smokers, various product liability suits.

- Government provision: As with lighthouses, education, and national defense.

- Pigovian taxes or subsidies intended to redress economic injustices or imbalances.

Economists prefer Pigovian taxes and subsidies as being the least intrusive and potentially the most efficient method to resolve externalities.

Government intervention may not always be needed. Traditional ways of life may have evolved as ways to deal with external costs and benefits. Alternatively, democratically-run communities can agree to deal with these costs and benefits in an amicable way. Externalities can sometimes be resolved by agreement between the parties involved. This resolution may even come about because of the threat of government action.

The first, and most common type of agreement, is tacit agreement through the political process. Governments are elected to represent citizens and to strike political compromises between various interests. Normally governments pass laws and regulations to address pollution and other types of environmental harm. These laws and regulations can take the form of "command and control" regulation (such as setting standards, targets, or process requirements), or environmental pricing reform (such as ecotaxes or other pigovian taxes, tradable pollution permits or the creation of markets for ecological services. The second type of resolution is a purely private agreement between the parties involved.

Ronald Coase argued that if all parties involved can easily organize payments so as to pay each other for their actions, then an efficient outcome can be reached without government intervention. Some take this argument further, and make the political claim that government should restrict its role to facilitating bargaining among the affected groups or individuals and to enforcing any contracts that result. This result, often known as the Coase Theorem, requires that

- Property rights are well defined

- People act rationally

- Transaction costs are minimal

If all of these conditions apply, the private parties can bargain to solve the problem of externalities.

This theorem would not apply to the steel industry case discussed above. For example, with a steel factory that trespasses on the lungs of a large number of individuals with pollution, it is difficult if not impossible for any one person to negotiate with the producer, and there are large transaction costs. Hence the most common approach may be to regulate the firm (by imposing limits on the amount of pollution considered "acceptable") while paying for the regulation and enforcement with taxes. The case of the vaccinations would also not satisfy the requirements of the Coase Theorem. Since the potential external beneficiaries of vaccination are the people themselves, the people would have to self-organize to pay each other to be vaccinated. But such an organization that involves the entire populace would be indistinguishable from government action.

In some cases, the Coase theorem is relevant. For example, if a logger is planning to clear-cut a forest in a way that has a negative impact on a nearby resort, the resort-owner and the logger could, in theory, get together to agree to a deal. For example, the resort-owner could pay the logger not to clear-cut – or could buy the forest. The most problematic situation, from Coase's perspective, occurs when the forest literally does not belong to anyone; the question of "who" owns the forest is not important, as any specific owner will have an interest in coming to an agreement with the resort owner (if such an agreement is mutually beneficial).

See also

Notes

- ^ De Bandt, O.; Hartmann, P. (1998), Risk Measurement and Systemic Risk: 37–84 http://www.imes.boj.or.jp/cbrc/cbrc-02.pdf

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Weiss, Rick (2008-04-30), "Report Targets Costs Of Factory Farming", Washington Post

- ^ Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production, Proc Putting Meat on The Table: Industrial Farm Animal Production in America, The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

- ^ Glaeser, Edward L. and Shapiro (2002). "The Benefits of the Home Mortgage Interest Deduction". Social Science Research Network.

References

- Definition

- Pigou, A.C. (1920). Economics of Welfare. Macmillan and Co.

- Baumol, W.J. (1972), ‘On Taxation and the Control of Externalities’, American Economic Review, 62(3), 307-322.

- Tullock, G. (2005). Public Goods, Redistribution and Rent Seeking. Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. ISBN 1-84376-637-X.

- Martin Weitzman (1974). "Prices vs. Quantities". The Review of Economic Studies. 41 (4): 477–491.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)