Tonality

Tonality is a system of music in which specific hierarchical pitch relationships are based on a key "center" or tonic. The term tonalité originated with Alexandre-Étienne Choron (1810) and was borrowed by François-Joseph Fétis in 1840 (Reti, 1958; Simms 1975, 119; Judd, 1998; Dahlhaus 1990). Although Fétis used it as a general term for a system of musical organization and spoke of types de tonalités rather than a single system, today the term is most often used to refer to Major-Minor tonality (also called diatonic tonality, common practice tonality, or functional tonality), the system of musical organization of the common practice period, and of Western-influenced popular music throughout much of the world today.

Characteristics and features

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (June 2008) |

Carl Dahlhaus (1990) lists the characteristic schemata of tonal harmony, "typified in the compositional formulas of the 16th and early 17th centuries," as the "complete cadence" (vollständige Kadenz), I-IV-V-I, I-IV-I-V-I, or I-ii-V-I; the circle of fifths progression: I-IV-vii-iii-vi-ii-V-I, and the "major-minor parallelism", minor: v-i-VII-III = major: iii-vi-V-I or minor: III-VII-i-v = major: I-V-vi-iii.

David Cope (1997) considers key, consonance or relaxation and dissonance or tension, and hierarchical relationships to be the three most basic concepts in tonality. In describing these tenets of tonal music, several known terms are used to refer to various elements of the tonal system.

Music is considered to be tonal if it includes most or all of the following features[citation needed]:

- it uses a Major or minor (diatonic) scale system

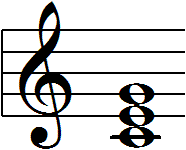

- it contains triadic harmonies (chords built from major and minor thirds)

- it has a tonic (central tone)

- it has a leading tone (7th scale degree a semitone below the tonic)

- resolution of active tones (that is, if a chord or note is played that doesn't sound final (like a leading tone 7th scale degree, in most circumstances), a more final-sounding chord or tone is played after it (like the tonic) to resolve the piece)

Since the mid-18th century, tonal music has been increasingly composed of a 12-note chromatic scale in a system of equal temperament. Tonal music makes reference to "scales" of notes selected as a series of steps from the chromatic scale.[citation needed] Most of these scales are of 5, 6, or 7 notes with the vast majority of tonal music pitches conforming to one of four specific seven-note scales: major, natural minor, melodic minor, and harmonic minor.[citation needed]

C major scale:

A natural minor scale:

Other scales or modes are often introduced for variety within the context of a major-minor tonal system without disturbing the diatonic nature of the work. The major scale predominates and the melodic minor contains nine pitches (seven with two alterable). The seven basic notes of a scale are notated in the key signature, and whether the piece is in the major or minor key is either stated in the title or implied in the piece (there is a major and minor key for each key signature). While other scales and modes are used in tonal music, particularly after 1890,[citation needed] these two scales are the reference point for most tonal music and its vocabulary.

Other important scales include the other church modes,[citation needed] the blues scale, the whole tone scale used by many Russian composers,[citation needed] pentatonic scale and the chromatic scale. Since none of these are the major or minor diatonic scales, music written exclusively with them is, by the definition above, not tonal.

Tone-centric music composed in other scale systems may be microtonal, and while microtonal music theory may draw from tonal theory, it is generally treated separately in textbooks and other works on music[weasel words]. However, within the tonal system, notes "between" the chromatic system are used in various contexts, including quarter tones and various effects such as portamento or glissando, where the instrumentalist moves between established notes of the diatonic scale. These are usually thought of[weasel words] as being for "colour" rather than harmonic function, and do not disturb the fundamental (diatonic) scale being used.

Chords are built from notes of a diatonic scale, or secondarily on chromatic notes treated as variations or embellishments of the basic scale. The identity of the scale is important in that the scale's steps used as roots determine the system of chord relationships. At any given time one scale degree is heard as the most important (the "tonic"), and the chord built on it, always a major or minor triad, is heard as the most forceful closure.

Roman numerals

In notation or analysis, each note or degree of the scale is often designated by a Roman numeral, or, less commonly, solfege:

| Function | Roman Numeral | Solfege |

| Tonic | I | Do/Ut |

| Supertonic | II | Re |

| Mediant | III | Mi |

| Sub-Dominant | IV | Fa |

| Dominant | V | Sol |

| Sub-Mediant | VI | La |

| Leading/Subtonic | VII | Ti/Si |

Roman numerals are most commonly used to describe triads in relation to the tonic, and are often written using a combination of upper and lower case numerals. The quality of triad (major, minor, diminished, or augmented) determines the case of the numeral; major and augmented triads require an upper case numeral, and minor and diminished triads require a lower case numeral. The triad built upon the first scale degree corresponds to the Roman numeral I (or i), the triad built on the second scale degree corresponds to the roman numeral II (or ii), and so on. Using Roman numerals to describe chords found in a piece of music highlights how the piece relates to the fundamental harmonic paradigms (I-IV-V-I, I-ii-V-I, etc.).

Chords

These numerals also may indicate chords which are built upon the indicated degree. This degree is then known as the root of that chord. Thus "I" describes the tonic chord, the chord built on the tonic note, at a given time. These chords are generally all triads (having three notes, built from thirds, and having a diatonic function).

The degree of a scale is both the pitch (frequency) of that note and that pitch's diatonic function (role), which is why chords are named by scale degree. Thus the notes of a chord do not have to be sounded simultaneously, and one to two notes may function as, or imply, a three (or more) note chord. Thus a chord described as "V" is based on the fifth note of the prevailing tonic scale (V-VII-II). In C Major, that would be a triad based on G, and would be the G Major triad (G-B-D). To describe a chord progression, the Roman numerals of the chords are listed. Thus IV-V-I describes a chord progression of a chord based on the fourth note of a scale, then one based on the fifth note of the scale, and then one on the first note of the scale.

Chords are then further named according to their quality or makeup, determined by the scale notes which lie a third and fifth (two thirds) above the degree a chord is built upon. Capital Roman numerals refer to the major chord, and lower-case Roman numerals refer to the minor chord. Quality is generally not as important as the chord's root.

This means that in the traditional major scale, the ii, iii and vi are minor chords, where as I, IV, V are major. The chord on the seventh note is a diminished triad and is written vii with a degree sign. Numbers attached to a chord indicate additional notes, and one of the most important chords in tonal harmony is the V7 chord, which is a four note chord that includes the fourth note of the tonic scale. The "7" refers to a note seven diatonic steps up from the fundamental note of the chord, not the seventh note of the tonic scale.

Inversion

A chord's root is determined by which note establishes the chord's relationship to the tonic and not which is in the bass, or the lowest played note. Thus chords are said to be "inverted" when this root note is not sounded as the lowest. For example in C Major C-E-G is the tonic chord. If C is not the lowest note played, it is said to be in "inversion". The first inversion would be E-G-C, and the second inversion would be G-C-E. Since inverted chords are also chords in their own right, in context a chord is sometimes thought to be inverted only when voice leading implies it.

Form

The traditional form of tonal music begins and ends on the tonic of the piece, and many tonal works move to a closely related key, such as the dominant of the main tonality (for example sonata form). Establishing a tonality is traditionally accomplished through a cadence which is two chords in succession which give a feeling of completion or rest - the most common being V7-I cadence. Other cadences are considered to be less powerful. The cadences determine the form of a tonal piece of music, and the placement of cadences, their preparation and establishment as cadences, as opposed to simply chord progressions, is central to the theory and practice of tonal music.

Harmony

Tonal music derives its form and rhetorical power from its utilization of standardized chord progressions.[citation needed] These chord progressions assign particular roles, or "functions", to the individual harmonies. Over time, the ways in which conventional chord progressions were used developed into a complex set of relationships that allowed any major, minor, augmented, or diminished triad, as well as most seventh chords, to be used in a given piece, as long as that usage was consistent with harmonic practice.[citation needed] The totality of paradigmatic harmonic relationships in classical tonal music is called functional harmony.

Consonance and dissonance

In the context of tonal organization a chord or a note is said to be "consonant" when it implies stability, and "dissonant" when it implies instability. This is not the same as the ordinary use of the words consonant and dissonant. A dissonant chord is in tension against the tonic, and implies that the music is distant from that tonic chord. "Resolution" is the process by which the harmonic progression moves from dissonant chords to consonant chords and follows counterpoint or voice leading. Voice leading is a description of the "horizontal" movement of the music, as opposed to chords which are considered the "vertical".

Traditional tonal music is described in terms of a scale of notes. On the notes of that scale are built chords. Chords in order form a progression. Progressions establish or deny a particular chord as being the tonic chord. The cadence is held to be the sequence of chords which establishes one chord as being the tonic chord; more powerful cadences create a greater sense of closure and a stronger sense of key. Chords have a function when it can be explained how they lead the music towards or away from a particular tonic chord. When the sense of which tonic chord is changed, the music is said to have "changed key" or "modulated". Roman numerals and numbers are used to describe the relationship of a particular chord to the tonic chord.

The techniques of accomplishing this process, are the subject of tonal music theory and compositional practice.

History and theory

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. (February 2009) |

Theories of tonal music are generally said to have begun with Jean-Philippe Rameau's Treatise on Harmony (1722), where he describes music written through chord progressions, cadences and structure. He claims that his work represents "the practice of the last 40 years", although this is probably not the case. Rameau's work, initially controversial, was introduced to Germany by Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg in 1757 and used Rameau's system to explain the music of Johann Sebastian Bach (Marpurg 1753–54). The vocabulary of describing notes in relationship to the tonic note, and the use of harmonic progressions and cadences becomes absorbed into the practice of Bach. Essential to this version of tonal theory are the chorale harmonizations of Bach, and the method by which a church melody is given a four part harmony by assigning cadences, and then creating a "natural" (in this case meaning 'the most direct') thoroughbass and then filling in the middle voices.

In 1821 Castil-Blaze used tonalité for what he called cordes tonales (today primary triads), the tonic, subdominant and dominant (chords I, IV and V respectively). All other chords were cordes melodiques.[citation needed] Hugo Riemann defined tonality as, "the special meaning [functions] that chords receive through their relationship to a fundamental sonority, the tonic triad."[citation needed]

Fétis (1844) defined tonality, specifically tonalité moderne as the, "set of relationships, simultaneous or successive, among the tones of the scale," allowing for other types de tonalités among different cultures. He considered tonalité moderne as "trans-tonic order" (having one established key, and allowing for modulation to other keys) and tonalité ancienne "uni-tonic order" (establishing one key and remaining in that key for the duration of the piece). He described his earliest example of tonalité moderne: "In the passage quoted here from Monteverdi's madrigal (Cruda amarilli, mm.9-19 and 24-30), one sees a tonality determined by the accord parfait [root position major chord] on the tonic, by the sixth chord assigned to the chords on the third and seventh degrees of the scale, by the optional choice of the accord parfait or the sixth chord on the sixth degree, and finally, by the accord parfait and, above all, by the unprepared seventh chord (with major third) on the dominant." (p.171)

Fétis believed that tonality, tonalité moderne, was entirely cultural, "For the elements of music, nature provides nothing but a multitude of tones differing in pitch, duration, and intensity by the greater or least degree...The conception of the relationships that exist among them is awakened in the intellect, and, by the action of sensitivity on the one hand, and will on the other, the mind coordinates the tones into different series, each of which corresponds to a particular class of emotions, sentiments, and ideas. Hence these series become various types of tonalities." (p.11f) "But one will say, 'What is the principle behind these scales, and what, if not acoustic phenomena and the laws of mathematics, has set the order of their tones?' I respond that this principle is purely metaphysical [anthropological]. We conceive this order and the melodic and harmonic phenomena that spring from it out of our conformation and education." (p.249) In contrast, Hugo Riemann believed tonality, "affinites between tones" or Tonverwandtschaften, was entirely natural and, following Moritz Hauptmann (1853), that the major third and perfect fifth were the only "directly intelligible" intervals, and that I, IV, and V, the tonic, subdominant, and dominant were related by the perfect fifths between their roots. (Dahlhaus 1990, p.101-2)

By the 1840s the practice of harmony had expanded to include more chromatic notes, a wider chord vocabulary, particularly the more frequent used of the diminished seventh chord - a four note chord of all minor thirds which could lead to any other chord. It is in this era that the word "tonality" becomes more commonly used. At the same time the elaboration of both the fugue and the sonata form in terms of key relationships becomes more rigorous, and the study of harmonic progressions, voice leading and ambiguity of key becomes more precise.

Theorists such as Edward Lowinsky, Hugo Riemann, and others pushed the date at which modern tonality began, and the cadence began to be seen as the definitive way that a tonality is established in a work of music (Judd, 1998).

In response Bernhard Meier instead used a "tonality" and "modality", modern vs ancient, dichotomy, with Renaissance music being modal. The term modality has been criticized by Harold Powers, among others. However, it is widely used to describe music whose harmonic function centers on notes rather than on chords, including some of the music of Bartók, Stravinsky, Vaughan Williams, Charles Ives and composers of minimalist music. This and other modal music is broadly and generally considered tonal.

In the early 20th century the vocabulary of tonal theory is decisively influenced by two theorists: composer Arnold Schoenberg whose Harmonielehre (Theory of Harmony) describes in detail chords, chord progressions, vagrant chords, creation of tonal areas, voice leading in terms of harmony. To Schoenberg, every note has "structural function" to assert or deny a tonality, based on its tendency to establish or undermine a single tonic triad as central. At the same time Heinrich Schenker was evolving a theory based on expansion of horizontal relationships. To Schenker the background of every successful tonal piece is based on a simple cadence, which is then elaborated and elongated in the middleground and the foreground. Though adherents of the two theorists argued back and forth, in the mid-century a synthesis of their ideas was widely taught as "tonal theory", most particularly Schenker's use of graphical analysis, and Schoenberg's emphasis on tonal distance.

The practice of jazz developed its own theory of tonality, stating that while the cadence is not central to establishing a tonality—the presence of the I and V chords and either the IV or ii chord in progression is. This theory emphasized the play of modal elements against tonal elements, in an effort to allow improvisation, and inflection of standard melodies. Among theorists influenced by this view are Meier, Schillinger and the be-bop school of Jazz.

While many regard the works of Schoenberg post 1911 as "atonal," one influential school of thought, to which Schoenberg himself belonged, argued that chromatic composition led to a "new tonality", this view is argued by George Perle in his works on "post diatonic tonality".[verification needed] The central idea of this theory is that music is always perceived as having a center, and even in a fully chromatic work, composers establish and disintegrate centers in a manner analogous to traditional harmony. This view is highly controversial, and remains a topic of intense debate.

However, tonality may be considered generally with no restrictions as to the date or place at which the music was produced, or (very little) restriction as to the materials and methods used. This definition includes much non-western music and western music before 17th century. By the middle of the twentieth century, it had become "evident that triadic structure does not necessarily generate a tone center, that nontriadic harmonic formations may be made to function as referential elements, and that the assumption of a twelve-tone complex does not preclude the existence of tone centers" (Perle 1991, 8). Much music that is commonly described as tonal is actually nonfunctional tonality such as in that of Claude Debussy, Steve Reich, Aaron Copland and many others.[citation needed] Centric is sometimes used to describe music which is not traditionally tonal but which nevertheless has a relatively strong tonal center. See: pitch center. Often the term "common practice tonality" is used specifically to refer to tonal music that utilizes the diatonic system of tonic/dominant relationship, whereas "tonal" or "tonality" refers more broadly to describe any music or musical practice that relies on or exhibits tonal centers and/or modalities, often with triadic organization and relatively consonant harmonies.

In the early 20th century, the tonality which had prevailed since the 1600s was seen to have reached a crisis or break down point. Because of the "increased use of ambiguous chords, the less probable harmonic progressions, and the more unusual melodic and rhythmic inflections", the syntax of functional harmony was loosened to the point where "At best, the felt probabilities of the style system had become obscure; at worst, they were approaching a uniformity which provided few guides for either composition or listening" (Meyer 1967, 241). This led to a series of responses, many of which were considered irreconcilable with tonal theory or tonality at all. At the same time, other composers and theorists maintained that tonality had been stretched but not broken. This led to more technical vocabularies to describe tonality, including pitch classes, pitch sets, graphical analysis, and describing works in terms, not of their notes, but of their dominant intervals.

While tonality is the most common form of organizing Western Music, it is not universal, [citation needed] nor is the seven-note scale universal.[citation needed] However, Alfred Einstein wrote, regarding the ancient civilizations, that in ancient China "the development from the non-semitonal pentatonic to the seven-note scale is certainly traceable, even though the old pentatonic always remained the foundation of its music" (Einstein 1954, 7). He similarly notes the same kind of thing regarding ancient Japan, and Java. Much folk music and the art music of many cultures focus on a pentatonic, or five-note scale, including Beijing Opera, the folk music of Hungary, and the musical traditions of Japan.

Pre-classical concert music was largely modal,[citation needed] as is much folk and some popular music.[citation needed] In the early 20th century many techniques were developed and applied to tonal music, such as non-tertian secundal or quartal music.[citation needed] Some, such as Benjamin Boretz,[citation needed] consider tonal theory a specific part of atonal theory or musical set theory, which is in turn part of a more general theory of music.[citation needed] Many composers such as Darius Milhaud and Philip Glass have been interested in bitonality. While at one point in the middle of the 20th century the influence of atonality was such that many classical composers interested in the twelve tone technique and serialism declared tonality "dead,"[citation needed] the postmodern age of composition which began in the mid-1970s with the advent of minimalism has been characterized by a dramatic return to the use of tonality by composers, especially in the U.S. Other composers such as Alan Hovhaness, Samuel Barber, Benjamin Britten, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and Lou Harrison, never abandoned tonality in the general sense, even at the height of atonal modernist influence in the middle decades of the 20th century.

Theoretical underpinnings

Tonality allows for a great range of musical materials, structures, meanings, and understandings. It does this through establishing a tonic, or central chord based on a pitch which is the lowest degree of a scale, and a somewhat flexible network of relations between any pitch or chord and the tonic similar to perspective in painting. This is what is meant by tonality having a hierarchical relationship, one triad, the tonic triad, is the "center of gravity" to which other chords are supposed to lead. Changing which chord is felt to be the tonic triad is referred to as "modulation".

As within a musical phrase, interest and tension may be created through the move from consonance to dissonance and back, a larger piece will also create interest by moving away from and back to the tonic and tension by destabilizing and re-establishing the key. Distantly related pitches and chords may be considered dissonant in and of themselves since their resolution to the tonic is implied. Further, temporary secondary tonal centers may be established by cadences or simply passed through in a process called modulation, or simultaneous tonal centers may be established through polytonality. Additionally, the structure of these features and processes may be linear, cyclical, or both. This allows for a huge variety of relations to be expressed through dissonance and consonance, distance or proximity to the tonic, the establishment of temporary or secondary tonal centers, and/or ambiguity as to tonal center. Music notation was created to accommodate tonality and facilitates interpretation.

The majority of tonal music assumes that notes spaced over several octaves are perceived the same way as if they were played in one octave or octave equivalency. Tonal music also assumes that scales have harmonic implication or diatonic functionality. This is generally held to imply that a note which has different places in a chord will be heard differently, and that therefore there is not enharmonic equivalency. In tonal music chords which are moved to different keys, or played with different root notes are not perceived as being the same, and thus transpositional equivalency and far less still inversional equivalency are not generally held to apply.

A successful tonal piece of music, or a successful performance of one, will give the listener a feeling that a particular chord — the tonic chord — is the most stable and final. It will then use musical materials to tell the musician and the listener how far the music is from that tonal center, most commonly, though not always, to heighten the sense of movement and drama as to how the music will resolve the tonic chord. The means for doing this are described by the rules of harmony and counterpoint (some influential theorists prefer the term "thoroughbass" instead of harmony, but the concept is the same). Counterpoint is the study of linear resolutions of music, while harmony encompasses the sequences of chords which form a chord progression.

Though modulation may occur instantaneously without indication or preparation, the least ambiguous way to establish a new tonal center is through a cadence, a succession of two or more chords which ends a section and/or gives a feeling of closure or finality, or series of cadences. Traditionally cadences act both harmonically to establish tonal centers and formally to articulate the end of sections, just as the tonic triad is harmonically central, a dominant-tonic cadence will be structurally central. The more powerful the cadence, the larger the section of music it can close. The strongest cadence is the perfect authentic cadence, which moves from the dominant to the tonic, most strongly establishes tonal center, and ends the most important sections of tonal pieces, including the final section. This is the basis of the "dominant-tonic" or "tonic-dominant" relationship. Common practice placed a great deal of emphasis on the correct use of cadences to structure music, and cadences were placed precisely to define the sections of a work. However, such strict use of cadences gradually gave way to more complex procedures where whole families of chords were used to imply particular distance from the tonal center. Composers, beginning in the late 18th Century began using chords (such as the Neapolitan, French or Italian Sixth) which temporarily suspended a sense of key, and by freely changing between the major and minor voicing for the tonic chord, thereby making the listener unsure whether the music was major or minor. There was also a gradual increase in the use of notes which were not part of the basic 7 notes, called chromaticism, culminating in post-Wagnerian music such as that by Mahler and Strauss and trends such as impressionism and dodecaphony.

One area of disagreement, going back to the origin of the term tonality, is whether, and to what degree, tonality is "natural" or inherent in acoustical phenomena, and whether, and to what degree, it is inherent in the human nervous system, or a psychological construct and, if the latter, whether it is inborn or learned, or some combination of these possibilities (Meyer 1967, 236). A viewpoint held by many theorists since the third quarter of the 19th century holds that diatonic scales and tonality arise from natural overtones (Riemann 1872, 1875, 1882, 1893, 1905, 1914–15; Schenker 1906–35; Hindemith 1937–70), following the publication in 1862 of the first edition of Helmholtz's On the Sensation of Tone (Helmholtz 1877).

Rudolph Réti differentiates between harmonic tonality, of the traditional kind found in homophony, and melodic tonality, as in monophony. In the harmonic kind tonality is produced through the V-I chord progression. He argues that in the progression I-x-V-I (and all progressions), V-I is the only step "which as such produces the effect of tonality," and that all other chord successions, diatonic or not, being more or less similar to the tonic-dominant, are "the composer's free invention." He describes melodic tonality as being "entirely different from the classical type," wherein, "the whole line is to be understood as a musical unit mainly through its relationship to this basic note [the tonic]," this note not always being the tonic that would be interpreted according to harmonic tonality. His examples are ancient Jewish and Gregorian chant and other Eastern music, and he points out how these melodies often may be interrupted at any point and returned to the tonic, yet harmonically tonal melodies, such as that from Mozart's The Magic Flute below, are actually "strict harmonic-rhythmic pattern[s]," and include many points "from which it is impossible, that is, illogical, unless we want to destroy the innermost sense of the whole line." (Reti, 1958)

- x = return to tonic near inevitable

- circled x = possible but not inevitable

- circle = impossible

- (Reti, 1958)

Consequently, he argues, melodically tonal melodies resist harmonization and only reemerge in western music after, "harmonic tonality was abandoned," as in the music of Claude Debussy: "melodic tonality plus modulation is [Debussy's] modern tonality." (page 23)

See also

External links

- Music Fundamentals: Tonal Music PDF

- Tonal Harmony Reference Materials for the Undergraduate Theory Student

- Tonality, Modality, and Atonality by Larry Solomon

- Basic guide to tonal theory

- The Tonal Centre "explains and demonstrates some of the key concepts of tonality"

- Algebra of Tonal Functions.

References

- Beswick, Delbert Meacham. 1951. "The Problem of Tonality in Seventeenth-Century Music." Ph.D. diss. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina.

- Jim Samson (1977) suggests the following discussions of tonality as defined by Fétis, Helmholtz, Riemann, D'Indy, Adler, Yasser, and others:

- Beswick, Delbert M. 1950. "The Problem of Tonality in Seventeenth Century Music". Ph.D. thesis. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina. p.1-29. OCLC accession number 12778863.

- Shirlaw, Matthew (1917). The Theory of Harmony: An Inquiry into the Natural Principles of Harmony; with an Examination of the Chief Systems of Harmony from Rameau to the Present Day. London: Novello & Co. (Reprinted New York: Da Capo Press, 1969. ISBN 0-306-71658-5.)

Sources

- Alembert, Jean le Rond D'. 1752. Elémens de musique, theorique et pratique, suivant les principes de m. Rameau. Paris: David l'aîné. Facsimile reprint, New York: Broude Bros., 1966.

- Choron, Alexandre. 1810. "Sommaire de l'histoire de la musique." In vol. 1 of François Fayolle and Alexandre Choron, Dictionnaire historique de musiciens. 2 vols. Paris: Valade et Lenormant, 1810–11.

- Cope, David. 1997. Techniques of the Contemporary Composer, p.12. New York, New York: Schirmer Books. ISBN 0-02-864737-8.

- Dahlhaus, Carl. 1990. Studies in the Origin of Harmonic Tonality. Translated by Robert O. Gjerdingen. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09135-8.

- Castile-Blaze. 1821. Dictionnaire de musique moderne. Paris: Au magazin de musique de la Lyre moderne.

- Fétis, Joseph. 1722. Traité complet de la théorie et de la pratique de l'harmonie contenant la doctrine de la science et de l'art, 2d ed., p.166. Brussels and Paris.

- Hauptmann, Moritz. 1853. Die Natur der Harmonik und der Metrik, p.21. Leipzig.

- Rameau, Jean-Philippe. 1737. Génération harmonique, ou Traité de musique théorique et pratique. Paris.

- Riemann, Hugo; cited in Gurlitt, W. (1950). "Hugo Riemann (1849-1919)".

- Einstein, Alfred. 1954. A Short History of Music, fourth American edition, revised. New York: Vintage Books.

- Gustin, Molly. 1969. Tonality. Philosophical Library. LCCN 68-0 – 0.

- Harrison, Lou. 1992. "Entune." Contemporary Music Review 6 (2), 9-10.

- Helmholtz, Hermann von. 1877. Die Lehre von den Tonempfindungen als physiologische Grundlage für die Theorie der Musik. Fourth edition. Braunschweig: F. Vieweg. English, as On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music. 2d English ed. translated, thoroughly rev. and corrected, rendered conformal to the 4th (and last) German ed. of 1877, with numerous additional notes and a new additional appendix bringing down information to 1885, and especially adapted to the use of music students, by Alexander J. Ellis. With a new introd. (1954) by Henry Margenau. New York, Dover Publications, 1954.

- Hindemith, Paul. Unterweisung im Tonsatz. 3 vols. Mainz, B. Schott's Söhne, 1937–70. First two volumes in English, as The Craft of Musical Composition, translated by Arthur Mendel and Otto Ortmann. New York: Associated Music Publishers; London: Schott & Co., 1941-42.

- Janata P, J. Birk, J. Van Horn J, M. Leman, B. Tillmann, and J. Bharucha. 2002. "The cortical topography of tonal structures underlying Western music." Science (Dec. 13).

- Judd, Cristle Collins. 1998. "Introduction: Analyzing Early Music", Tonal Structures of Early Music (ed. Judd). New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8153-2388-3.

- Kilmer, Anne Draffkorn, Richard L. Crocker, and Robert R. Brown. 1976. Sounds from Silence, Recent Discoveries in Ancient Near Eastern Music. LP sound recording, 33 1/3 rpm, 12 inch, with bibliography (23 p. ill.) laid in container. [n.p.]: Bit Enki Records. LCC#75-750773 /R

- Marpurg, Friedrich Wilhelm. 1753–54. Abhandlung von der Fuge nach dem Grundsätzen der besten deutschen und ausländischen Meister. 2 vols. Berlin: A. Haude, und J.C. Spener.

- ———. 1757. Systematische Einleitung in die musikalische Setzkunst, nach den Lehrsätzen des Herrn Rameau, Leipzig: J. G. I. Breitkopf. [translation of D'Alembert 1752]

- Meyer, Leonard B. 1967. Music, the Arts, and Ideas: Patterns and Predictions in Twentieth-Century Culture. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Perle, George. 1978. Twelve-Tone Tonality. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20142-6. (reprinted 1992)

- Perle, George. 1991. Serial Composition and Atonality: An Introduction to the Music of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern, sixth edition, revised. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07430-0

- Pleasants, Henry. 1955 The Agony of Modern Music, Simon & Shuster, N.Y., LCC#54-12361.

- Rameau, Jean-Phillipe. 1722. Traité de l’harmonie réduite à ses principes naturels. Paris: Ballard.

- ———. 1726. Nouveau Systême de Musique Theorique, où l'on découvre le Principe de toutes les Regles necessaires à la Pratique, Pour servir d'Introduction au Traité de l'Harmonie. Paris: L'Imprimerie de Jean-Baptiste-Christophe Ballard.

- ———. 1737. Génération harmonique, ou Traité de musique théorique et pratique. Paris: Prault fils.

- ———. 1750. Démonstration du Principe de L'Harmonie, Servant de base à tout l'Art Musical théorique et pratique. Paris: Durand et Pissot.

- Reti, Rudolph (1958). Tonality, Atonality, Pantonality: A Study of Some Trends in Twentieth Century Music. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-20478-0.

- Riemann, Hugo. 1872. "Über Tonalität." Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 68.

- ———. 1875. “Die objective Existenz der Untertöne in der Schallwelle.” Allgemeine Musikzeitung 2:205–6, 213–15.

- ———. 1882. Die Natur der Harmonik. Sammlung musikalischer Vorträge 40, ed. Paul Graf Waldersee. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel.

- ———. 1893. Vereinfachte Harmonielehre oder die Lehre von den tonalen Funktionen der Akkorde. London & New York: Augener & Co. (2d ed. 1903.) Translated 1895 as Harmony Simplified, or the Theory of the Tonal Functions of Chords. London: Augener & Co.

- ———. 1905. "Das Problem des harmonischen Dualismus." Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 101:3–5, 23–26, 43–46, 67–70.

- ———. 1914–15. "Ideen zu einer 'Lehre von den Tonvorstellungen'." Jahrbuch der Musikbibliothek Peters 1914–15: 1–26.

- Samson, Jim. 1977. Music in Transition: A Study of Tonal Expansion and Atonality, 1900-1920. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-02193-9.

- Schellenberg, E. Glenn, and Sandra E. Trehub. 1996. "Natural Musical Intervals: Evidence from Infant Listeners" Psychological Science Vol. 7, no. 5 (September): 272-77.

- Schenker, Heinrich. 1906–35. Neue musikalische Theorien und Phantasien. 3 vols. in 4. Vienna and Leipzig: Universal Edition.

- Schenker, Heinrich. 1979. Free composition, translated and edited by Ernst Oster. New York: Longman, 1979. Translation of Neue musikalische Theorien und Phantasien, 3. Bd., Der freie Satz. ISBN 0-582-28073-7

- Schenker, Heinrich. 1987. Counterpoint, translated by John Rothgeb and Jürgen Thym; edited by John Rothgeb. 2 vols. New York: Schirmer Books; London: Collier Macmillan. Translation of Neue musikalische Theorien und Phantasien, 2. Bd., Kontrapunkt. ISBN 0-02-873220-0

- Schenker, Heinrich (1954). Harmony. trans. Elisabeth Mann-Borgese. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 280916.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|origmonth=,|accessmonth=,|month=, and|origdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Translation of Neue musikalische Theorien und Phantasien, 1. Bd., Harmonielehre. (Reprinted Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1973, ISBN 0-262-69044-6) - Schoenberg, Arnold. 1978. Theory of Harmony, translated by Roy E. Carter. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03464-3. Reprint ed. 1983, ISBN 0-520-04945-4. Pbk ed. 1983, ISBN 0-520-04944-6.

- Simms, Bryan. 1975. "Choron, Fétis, and the Theory of Tonality." Journal of Music Theory 19, no. 1 (Spring): 112–38.

- Thomson, William. 1999. Tonality in Music: A General Theory. San Marino, Calif.: Everett Books. ISBN 0-940459-19-1.

- West, M. L. 1994. "The Babylonian Musical Notation and the Hurrian Melodic Texts." Music and Letters 75, no. 2 (May): 161–79.