Tour de France

| |

|---|---|

| Tour de France | |

| Local name | Le Tour de France |

| Region | France and nearby countries |

| Date | July 5 to 27 (2008) |

| Type | Stage Race (Grand Tour) |

| General Director | Christian Prudhomme |

| History | |

| First race | 1903 |

| Number of races | 95 (2008) |

| First winner | |

| Most wins | |

| Latest winner | |

| Most career Yellow Jerseys | |

| Most career stage wins | |

The Tour de France is an annual bicycle race that covers more than 3,500 kilometres (2,200 mi) throughout France and a bordering country. The race usually lasts 23 days and attracts cyclists from around the world. The race is broken down into day-long segments, called stages. Individual times to finish each stage are totaled to determine the overall winner for the race. The rider with the least elapsed time each day wears a yellow jersey[1] The course changes every year but it has always finished in Paris. There are similar races in Italy and Spain but the Tour de France is the oldest, the most prestigious and the best known.

Description

The Tour de France is a bicycle race that is known around the world. It is possible to win without winning a stage, as Greg LeMond did in 1990. Although the number of stages varies, the modern Tour typically has 20, with a total length of 3,000 to 4,000 kilometres (1,800 to 2,500 mi). The shortest Tour was in 1904 at 2,420 km, the longest in 1926 at 5,745 km. [2] The 2007 Tour was 3,569.9 km long.[2] The three weeks usually include two rest days, sometimes used to transport riders between stages. The race alternates between clockwise and counter-clockwise circuits of France. The combination of endurance and strength needed led the New York Times to say in 2006 that the "Tour de France is arguably the most physiologically demanding of athletic events." The effort was compared to "running a marathon several days a week for nearly three weeks", while the total elevation of the climbs was compared to "climbing three Everests."[3]

The number of riders varies annually. There are usually 20 to 22 teams of nine riders. Entry is by invitation. The organizers have used UCI points to give some teams automatic entry. Others are invited to make up the numbers. Each team, named after its sponsor, wears a distinctive jersey. Team members help each other and are followed by managers and mechanics.

Riders are judged by accumulated time, known as the general classification. Riders are often awarded time bonuses as well as prizes. There are subsidiary competitions (see below), some with distinctive jerseys for the best rider.

Most stages are in France though it is common to visit Italy, Spain, Switzerland, Belgium, Luxembourg, Germany, the Netherlands, Ireland, and Great Britain. Stages can be flat, undulating or mountainous. Riders generally start each day together with the first over the line winning, but stages can also be time trials for individuals or teams. The overall winner is usually a master of the mountains and time trials.

Since 1975 the finish has been on the Champs-Élysées in Paris. Before 1975, the race finished at the Parc des Princes stadium in western Paris and at the Piste Municipale.

History

The first daily sports newspaper in France at the end of the 19th century was Le Vélo[4]. It sold 80,000 copies a day.[5] France was split over a soldier, Alfred Dreyfus, found guilty of selling secrets to the Germans. Le Vélo stood for Dreyfus's innocence while some of its biggest advertisers, notably Albert de Dion, owner of the De Dion-Bouton car works, believed him guilty.[6] Angry scenes followed between the advertisers and the editor, Pierre Giffard, and the advertisers started a rival paper.[7]

The Tour de France began to promote that rival, L'Auto. It was to outdo the Paris-Brest et retour organised by Giffard. The idea for a round-France race came from L'Auto's chief cycling journalist, 26-year-old Géo Lefèvre.[8] He and the editor, Henri Desgrange discussed it after lunch on 20 November 1902.[8] L'Auto announced the race on 19 January 1903. The plan was a five-week race from 31 May to 5 July. This proved too daunting and only 15 riders entered. Desgrange cut the length to 19 days, changed the race dates to 1 July to 19 July, and offered a daily allowance.[9] He attracted 60 entrants, not just professionals but amateurs, some unemployed, some simply adventurous.[8]

The demanding nature of the race (the stages averaged 400 km and could run through the night),[10] caught public imagination. L'Auto's circulation rose from 25,000 to 65,000;[8] by 1908 it was a quarter of a million, and during the 1923 Tour 500,000. The record claimed by Desgrange was 854,000 during the 1933 Tour.[11]

No teams from Italy, Germany or Spain participated in the 1939 Tour de France because of political tensions preceding World War II, and the race was not held again until 1947, although other races were held in that period (see Tour de France during the Second World War).

Today, the Tour is organized by the Société du Tour de France, a subsidiary of Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO), which is part of the media group that owns L'Équipe.

Mountains

Desgrange worried he was asking too much of competitors and stayed away in 1903, sending Lefèvre instead. His route included one mountain pass - the Ballon d'Alsace in the Vosges [12] - but the Pyrenees were not included until 1910. In that year the race rode, or more walked, first the col d'Aubisque and then the nearby Tourmalet. Desgrange once more stayed away. Both climbs were mule tracks, a demanding challenge on heavy, ungeared bikes ridden by men with spare tyres around their shoulders and their food, clothing and tools in bags hung from their handlebars. The eventual winner, Octave Lapize, was second to the top of the Aubisque. He told waiting officials that they were "killers" (assassins).[13]

Desgrange was confident enough after the Pyrenees to include the Alps in 1911.[14]

Passes such as the Tourmalet have been made famous by the Tour and attract amateur cyclists every day in summer to test their fitness on roads used by champions. The difficulty of a climb is established by its steepness, length and its position on the course. The easiest are graded 4, most of the hardest as 1 and the exceptional (such as the Tourmalet) as beyond classification, or hors catégorie. Famous hors catégorie peaks include the Col du Tourmalet, Mont Ventoux, Col du Galibier, the climb to the ski resort of Hautacam, and Alpe d'Huez.

Distances

The Tour originally ran round the perimeter of France. Cycling was an endurance sport and the organisers realised the sales they would achieve by creating supermen of their competitors. Night riding was dropped after the second Tour in 1904, when there had been persistent cheating when judges couldn't see riders.[15] That reduced the daily and overall distance but the emphasis remained on endurance. Desgrange said his ideal race would be so hard that only one rider would make it to Paris.[16]

A succession of doping scandals in the 1960s, culminating in the death of Tom Simpson in 1967, led the Union Cycliste Internationale to limit daily and overall distances and to impose rest days. It was then impossible to follow the frontiers and the Tour more and more zig-zagged across the country, sometimes with unconnected days' races linked by train, while still maintaining some sort of loop. The modern Tour typically has around 20 daily stages and a total of 3,000 to 4,000 kilometres (1,800 to 2,500 mi). The shortest Tour was in 1904 at 2,420 km, the longest in 1926 at 5,745km.[2] The 2007 Tour was 3,569.9 km long.[2]

Early rules

Desgrange and his Tour invented bicycle stage racing.[17] Desgrange experimented with judging by elapsed time[18] and then by points for placings each day.[19] He stood out against multiple gears and for many years insisted riders use wooden rims, fearing the heat of braking while coming down mountains would melt the glue that held the tyres.

His dream was a race of individuals. He invited teams but forbade their members to pace each other. He then went the other way and briefly ran the Tour as a giant team time-trial, teams starting separately with members pacing each other. He demanded riders mend their bicycles without help. He demanded they use the same bicycle from start to end. He at first allowed riders who dropped out one day to continue the next for daily prizes but not the overall prize. He allowed teams who lost members in the team time-trial years to recruit fresh replacements.

Above all, he conducted a campaign against the sponsors, bicycle factories, he was sure were undermining the spirit of a Tour de France of individuals.

National teams

The first Tours were for individuals and members of sponsored teams. There were two classes of race, one for the aces, the other for the rest, with different rules.[20] By the end of the 1920s, however, Desgrange believed he could not beat what he believed were the underhand tactics of bike factories.[21][22] When the Alcyon team contrived to get Maurice De Waele to win even though he was sick,[23] he said "My race has been won by a corpse" and in 1930 admitted only teams representing their country or region.[23][24]

National teams contested the Tour until 1961.[25] The teams were of different sizes. Some nations had more than one team and some were mixed in with others to make up the number. National teams caught the public imagination but had a snag: that riders might normally have been in rival trade teams the rest of the season. The loyalty of riders was sometimes questionable, within and between teams.

Touriste-routiers and regionals

The first Tours were open to whoever wanted to compete. Most riders were in teams who looked after them. The private entrants were called touriste-routiers - tourists of the road - and were allowed to take part provided they make no demands on the organisers. Some of the Tour's most colourful characters have been touriste-routiers. One finished each day's race and then performed acrobatic tricks in the street to raise the price of a hotel.

There was no place for individuals in the post-1930s teams and so Desgrange created regional teams, generally from France, to take in riders who would not otherwise have qualified. The original touriste-routiers mostly disappeared but some were absorbed into regional teams.

Return of trade teams

Riders in national teams wore the colours of their country and a small cloth panel on their chest that named the team for which they normally rode. Sponsors were always unhappy about releasing their riders into anonymity for the biggest race of the year and the situation became critical at the start of the 1960s. Sales of bicycles had fallen and bicycle factories were closing.[26] There was a risk, the trade said, that the industry would die if factories weren't allowed the publicity of the Tour de France.

The Tour returned to trade teams in 1962,[27] although with further problems. Doping had become a problem and tests were introduced for riders. Riders went on strike near Bordeaux in 1966 [28][29] and the organisers suspected sponsors provoked them. The Tour returned to national teams for 1967 and 1968[30] as "an experiment"[31] The author Geoffrey Nicholson identified a further reason: opposition to closure of roads by a race criticised as crassly commercial[32][33] He said:

What the Tour did to placate the opposition in 1967 was to play the patriotic card. It scrapped trade teams in favour of national teams... since a contest between squads in French and Belgian colours would appear less blatantly commercial than one between Ford-France-Gitane and Flandria-Romeo. 'It was being done,' said L'Équipe, the voice of the Tour, 'in response to the noble and superior interests of the race, to the wishes of the public and the desires of the public authorities.'[34]

The sponsors had to accept the change, but did so with ill-grace. The new arrangement, they argued, was basically unfair: they paid the riders' salaries all summer only to be denied publicity from the season's major event. They also pointed to the danger of collusion between trade-team colleagues of different nationalities... Indeed loyalties were put under so much strain that the experiment was dropped after only two seasons.[34]

The Tour returned to trade teams in 1969[35] with a suggestion that national teams could come back every few years. It never happened.

Organisers

The first organiser was Henri Desgrange, although daily running of the 1903 race was by Lefèvre. He followed riders by train and bicycle. In 1936 Desgrange had a prostate operation. At the time, two operations were needed; the Tour de France was due to fall between them. Desgrange persuaded his surgeon to let him follow the race.[36] The second day proved too much and, in a fever at Charleville, he retired to his château at Beauvallon. Desgrange died at home on the Mediterranean coast on 16 August 1940.[36] The race was taken over by his deputy, Jacques Goddet.[37] War interrupted the Tour. The German Propaganda Staffel wanted it to be run and offered facilities otherwise denied, in the hope of maintaining a sense of normality.[36][38] They offered to open the borders between German-occupied France in the north and nominally independent Vichy France in the south but Goddet refused.[36][39]

In 1944, L'Auto was closed - its doors nailed shut - and its belongings, including the Tour, sequestrated by the state for publishing articles too close to the Germans.[40] Rights to the Tour were therefore owned by the government. Jacques Goddet was allowed to publish another daily sports paper, L'Équipe, but there was a rival candidate to run the Tour: a consortium of Sports and Miroir Sprint. Each organised a candidate race. L'Équipe and Le Parisien Libéré had La Course du Tour de France[41] and Sports and Miroir Sprint had La Ronde de France. Both were five stages, the longest the government would allow because of shortages.[42] L'Équipe's race was better organised and appealed more to the public because it featured national teams which had been successful before the war, when French cycling was at a high. L'Équipe was given the right to organize the 1947 Tour de France.[36]

L'Équipe's finances were never sound and Goddet accepted an advance by Émilion Amaury, who had supported his bid to run the post-war Tour.[36] Amaury was a newspaper magnate whose condition was that his sports editor, Félix Lévitan should join Goddet for the Tour.[36] The two worked together, Goddet running the sporting side and Lévitan the financial.

Lévitan began to recruit sponsors, sometimes accepting prizes in kind if he could not get cash.[43] He introduced the finish of the Tour at the Avenue des Champs-Élysées in 1975. He left the Tour on 17 March 1987 after losses by the Tour of America, in which he was involved. The claim was that it had been cross-financed by the Tour de France.[36] Lévitan insisted he was innocent but the lock to his office was changed and his job was over.[36] Goddet retired the following year. They were replaced by a cognac salesman called Jean-François Naquet-Radiguet and a year later by Jean-Marie Leblanc. Christian Prudhomme replaced Leblanc in 2005, having been assistant organiser for two years.

Prudhomme works for the 'Société du Tour de France,' a subsidiary of Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO), which is part of the media group that owns 'L'Équipe.

The Tour Today

Famous stages

The race has finished since 1975 with laps of the Champs-Élysées. This stage rarely challenges the leader because it is flat and the leader usually has too much time in hand to be denied. But in 1987, Pedro Delgado broke away on the Champs to challenge the 40-second lead held by Stephen Roche. He and Roche finished in the peloton and Roche won the Tour.

In 1989 the last stage was a time trial. Greg LeMond overtook Laurent Fignon to win by eight seconds, the closest margin.

The climb of Alpe d'Huez is a favourite, providing a stage in most Tours. In 2004, a time trial ended at Alpe d'Huez. Riders complained about abusive spectators and the stage may not be repeated.[44][45] Mont Ventoux is often claimed to be the hardest in the Tour because of the harsh conditions.

To host a stage start or finish brings prestige and business to a town. The prologue and first stage are particularly prestigious. Usually one town will host the prologue (too short to go between towns) and the start of stage 1. In 2007 director Christian Prudhomme said that "in general, for a period of five years we have the Tour start outside France three times and within France twice."[46]

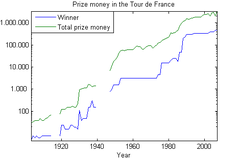

Prize money

Prize money has always been awarded. From 20,000 old francs the first year,[47] prize money has increased each year. Prizes and bonuses are awarded daily for and for final placings at the end of the race. In 2006, more than €3,000,000 (US$4,800,000) was awarded, the winner receiving €450,000 (US$720,000).[48]

The Souvenir Henri Desgrange, in memory of the founder of the Tour, is awarded to the first rider over the Col du Galibier where his monument stands,[48] or to the first rider over the highest col in the Tour. In 2008 it was awarded for traversing the Col de la Bonette.

The Souvenir Jacques Goddet, in memory of the first director of the Tour, is awarded to the first rider over the Col du Tourmalet where his monument stands.[48]

Classification jerseys

The aim of riders is to win overall but there are three further competitions: points, mountains and for the best young rider. The leaders of the competitions wear a distinctive jersey, awarded after each stage. When a single rider is entitled to more than one jersey, he wears the most prestigious and the second rider in the other classification wears the jersey. The overall and points competitions may be led by the same rider: the fastest on time will wear the yellow jersey and the rider second in the points competition will wear the green jersey.

The Tour's colours have been adopted by other races and thus have meaning within cycling generally. For example, the Tour of Britain has yellow, green, and polka-dot jerseys with the same meaning as the Tour. The Giro d’Italia differs in awarding the leader a pink jersey, being organized by La Gazzetta dello Sport, which has pink pages.

Overall leader

The maillot jaune is worn by the general classification leader. The winner of the first Tour wore not a yellow jersey but a green armband.[8] The first yellow was first awarded formally to Eugène Christophe, for the stage from Grenoble on 19 July 1919.[49] However, the Belgian rider Philippe Thys, who won in 1913, 1914 and 1920, recalled in the Belgian magazine Champions et Vedettes when he was 67 that he was awarded a yellow jersey in 1913 when Henri Desgrange asked him to wear a coloured jersey. Thys declined, saying making himself more visible would encourage others to ride against him.[50][8] He said:

- He then made his argument from another direction. Several stages later, it was my team manager at Peugeot, (Alphonse) Baugé, who urged me to give in. The yellow jersey would be an advertisement for the company and, that being the argument, I was obliged to concede. So a yellow jersey was bought in the first shop we came to. It was just the right size, although we had to cut a slightly larger hole for my head to go through.[50][51][n 1]

He spoke of the next year, when "I won the first stage and was beaten by a tyre by Bossus in the second. On the following stage, the maillot jaune passed to Georget after a crash."

The Tour historian Jacques Augendre called Thys "a valorous rider... well-known for his intelligence" and said his claim "seems free from all suspicion". But: "No newspaper mentions a yellow jersey before the war. Being at a loss for witnesses, we can't solve this enigma."[52]

The first rider to wear the yellow jersey from start to finish was Ottavio Bottecchia of Italy in 1924.[53] The first company to pay a daily prize to the wearer of the yellow jersey - known as the "rent" - was a wool company, Sofil, in 1948.[54] The greatest number of riders to wear the yellow jersey in a day is three: Nicolas Frantz, André Leducq and Victor Fontan shared equal time for a day in 1929 and there was no rule to split them.[54]

Points classification

The maillot vert (green jersey) is awarded for sprint points. At the end of each stage, points are earned by the riders who finish first, second, etc. Points are higher for flat stages, as sprints are more likely, and less for mountain stages, where climbers usually win. In the current rules, there are five types of stages: flat stages, intermediates stages, mountain stages, individual time trial stages and team time trial stages. The number of points awarded at the end of each stage are:

Flat stages

Flat stages- 35, 30, 26, 24, 22, 20, 19, 18, 17, 16, 15, 14, 13, 12, 11, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2 and 1 points are awarded to the first 25 riders across the finish.

Medium-mountain stages

Medium-mountain stages- 25, 22, 20, 18, 16, 15, 14, 13, 12, 11, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 points are awarded to the first 20 riders across the finish.

High-mountain stages

High-mountain stages- 20, 17, 15, 13, 12, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 points are awarded to the first 15 riders across the finish.

Time-trials

Time-trials- 15, 12, 10, 8, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 points are awarded to the top 10 finishers of the stage.

In addition, stages can have one or more intermediate sprints: 6, 4, and 2 points are awarded to the first three cyclists passing these lines.

In case of a tie, the number of stage wins determine the green jersey, then the number of intermediate sprint victories, and finally, the rider's standing in the overall classification.

The points competition began in 1953, to mark the 50th anniversary. It was called the Grand Prix du Cinquentenaire and won by Fritz Schaer of Switzerland. The first sponsor was La Belle Jardinière. The current sponsor is Pari Mutuel Urbain, a state betting company.[55]

King of the Mountains

The King of the Mountains wears a white jersey with red dots (maillot à pois rouges), inspired by a jersey that Félix Lévitan saw at the Vélodrome d'Hiver in Paris in his youth. The competition gives points to the first to top designated hills and mountains.

Climbs rated "hors catégorie" (HC): 20, 18, 16, 14, 12, 10, 8, 7, 6 and 5.

Category 1: 15, 13, 11, 9, 8, 7, 6 and 5.

Category 2: 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, and 5.

Category 3: 4, 3, 2 and 1.

Category 4: 3, 2 and 1.

For the last climb of a stage, points are doubled for HC and categories one and two.

The best climber was first recognised in 1933, prizes were given from 1934 and the jersey was introduced in 1975.[55]

Other classifications

The maillot blanc (white jersey) is for the best rider under 25 on January 1 that year.

The prix de la combativité goes to the rider who most animates the day, usually by trying to break clear of the field. The most combative rider wears a number printed white-on-red instead of black-on-white next day. An award goes to the most aggressive rider throughout the Tour. Already in 1908 a sort of combativity award was offered, when Sports Populaires and L'Education Physique created Le Prix du Courage, 100 francs and a silver gilt medal for "the rider having finished the course, even if unplaced, who is particularly distinguished for the energy he has used.".[53][56] The modern competition started in 1958.[57][53] In 1959, a Super Combativity award for the most combative cyclist of the Tour was awarded. It was initially not rewarded every year, but since 1981 it has been given annually.

The team prize is assessed by adding the time of each team's best three riders each day. The competition does not have its own jersey but since 2006 the leading team has worn numbers printed black-on-yellow. The competition has existed from the start; the most successful trade team is Alcyon, which won from 1909 to 1912 and from 1927 to 1929. The best national teams are France and Belgium, with 10 wins each.[55]

Historical jerseys

Previously, there was a red jersey for points awarded to the first three to pass intermediate points during the stage. These sprints also scored points towards the green jersey and bonuses towards the overall classification. The sprints remain, with points for the green jersey. The red jersey was abolished in 1989.[58]

There was also a combination jersey, scored on a points system based on standings for the yellow, green, red, and polka-dot jerseys. The design was a patchwork, with areas resembling each individual jersey design. This was abolished in the same year as the red jersey.

Lanterne rouge

The rider who has taken most time is called the lanterne rouge (Template:Lang-fr) and in past years sometimes carried a small red light beneath his saddle. Such was sympathy that he could command higher fees in the round-the-houses races that followed the Tour. The custom died along with the races. For some years the organisers experimented with sending home the last rider every day, to encourage more competitive racing.

Stages

Mass-start stages

Riders in most stages start together. The first kilometres, the départ fictif, are a rolling start without racing. The real start, the départ réel is announced by the Tour director's waving a white flag.

Riders are permitted to touch, but not push or nudge, and to slipstream (see drafting). The first to cross the line wins. In the first week, this leads to spectacular mass sprints.

All riders in a group finish in the same time as the lead rider. This avoids dangerous mass sprints. It is not unusual for the entire field to finish in a group, taking time to cross the line but being credited with the same time.

Time bonuses are often awarded to the first three at intermediate sprints and stage finishes. Riders who crash in the last three kilometres are credited with the time of the group they were with.[59] This prevents riders being penalised for accidents that do not reflect their performance on the stage, given that crashes in the final kilometre can be pileups hard to avoid. The final kilometre is indicated by a red triangle - the flamme rouge - above the road.

Stages in the mountains almost always cause major shifts in the general classification. On ordinary stages, most riders can stay in the peloton to the finish; during mountain stages, some lose 40 minutes. The mountains often decide the Tour. Mountain stages bring spectators who line the roads by the thousands.

Individual time trials

In an individual time trial each rider rides individually against the clock. The first stage is often a short trial, a prologue, to decide who wears yellow on the opening day.

There are usually two or three time trials . One may be a team time trial. Traditionally the final time trial has been the penultimate stage, and determines the winner before the final ordinary stage which is not ridden competitively until the last hour.

Team time trial

A team time trial (TTT) is a race against the clock in which each team rides alone. The time is that of the fifth rider. Riders more than a bike-length behind their teams are awarded their own times. The TTT has been criticised for favouring strong teams and handicapping strong riders in weak teams. The most recent TTT was held in 2005.

Culture

The Tour is important for fans in Europe. Millions[60] line the route, some having camped a week to get the best view. The journalist Pierre Chany wrote:

- The Tour de France has the major fault of dividing the country, the smallest hamlets, even families, into rival factions. I know a man who grabbed his wife and held her on the grill of a lighted stove, sitting with her dress pulled up, to punish her for favouring Jacques Anquetil while he admired Raymond Poulidor. The following year, the woman became a Poulidoriste, but too late: the husband had changed his allegiance to Felice Gimondi. The last I heard, they were digging their heels in and the neighbours were complaining.[61]

Part of the crowd each day is Didi Senft who, in a red devil costume, has been the Tour devil or El Diablo since 1993. The inspiration is attributed to the final kilometre of each stage, indicated by La Flamme Rouge, a red triangle, over the road.

It is common for farmers to build dioramas out of hay or mowed into the fields, depicting bicycles and "vive le tour." There was a competition for the best in 2008.

A carnival atmosphere prevails before the riders pass. Any cyclist is free to attempt the course in the morning, after which a cavalcade of advertising vehicles passes, blaring music and tossing hats, souvenirs, sweets and samples. As word passes that the riders are approaching, fans sometimes encroach on the road until they are an arm’s length from riders.

Customs

The riders temper their competitiveness with a code of conduct. It is unsporting to attack a leading rider delayed by misfortune. Attacking in the feed zone is not seen as sporting. Not sticking to customs can lead to animosity. Unless the gap between the top two is close, riders generally do not attack on the final stage, leaving the leader to his glory. Rider number 13 is allowed to wear one of his numbers upside down.

Social significance

The Tour de France appealed from the start not just for the distance and its demands but because it appealed to a wish for national unity,[62] a call to what Maurice Barrès called the France "of earth and deaths" or what Georges Vigarello called "the image of a France united by its earth."[63]

The image had been started by the 1877 travel/school book Le Tour de la France par deux enfants.[n 2] It told of two boys, André and Julien, who "in a thick September fog left the town of Phalsbourg in Lorraine to see France at a time when few people had gone far beyond their nearest town."

The book sold six million copies by the time of the first Tour de France[62], the biggest selling book of 19th century France (other than the Bible).[64] It stimulated a national interest in France, making it "visible and alive", as its preface said. There had already been a car race called the Tour de France but it was the publicity behind the cycling race, and Desgrange's drive to educate and improve the population,[65] that inspired the French to know more of their country.[66]

The academic historians Jean-Luc Boeuf and Yves Léonard say most people in France had little idea of the shape of their country until L'Auto began publishing maps of the race. They wrote:

At the start of the 20th century, the French were still largely ignorant (connaissent encore très mal) of the geography of their country. Maps were rare and little used, even at school. The physical shape of France and its contours remained an unknown for most Frenchmen... Efforts to interest school children in the image in general and maps in particular were in vain. The book Tour de France par Deux Enfants didn't have a map of France before its 1905 edition, by which time it had sold seven million copies![67]

By the maps of France [that it published], the Tour de France became at the same time a teacher, in printing a map of the contours of the country - which was rare at least until the Great War - and populist in portraying France as a hexagon, a France not only amputated from 1903 of its "lost provinces" but also its overseas possessions and Corsica, never visited in a century and still missing from maps of the Tour de France.[67][n 3]

The Tour de France has also given the language a word for a popular but persistent loser. Raymond Poulidor never won the Tour de France but was more popular than his rival, Jacques Anquetil, who won five times and unfailingly beat him. Poulidor is now associated with bad luck or a hard life, as an article by Jacques Marseille showed in Le Figaro when it was headlined "This country is suffering from a Poulidor Complex".[68][69]

The Tour in the arts

The Tour has inspired several popular songs in France, notably P’tit gars du Tour (1932), Les Tours de France (1936) and Faire le Tour de France (1950). Kraftwerk had a hit with Tour de France in 1983 - described as a minimalistic "melding of man and machine".[70] - and produced an album, Tour de France Soundtracks in 2003, the centenary of the Tour. The race inspired Queen's 1978 single Bicycle Race as it passed Freddie Mercury's hotel.

In films, the Tour was background for Cinq Tulipes Rouges (1949) by Jean Stelli, in which five riders are murdered. La Course en Tête (1974) followed Eddy Merckx and was selected for the Cannes Film Festival. A burlesque in 1967, Les Cracks by Alex Joffé, with Bourvil et Monique Tarbès, also featured him. Patrick Le Gall made Chacun son Tour (1996). Le Vélo de Ghislain Lambert (2001) featured the Tour of 1974.

In 2005, three films chronicled a team. The German Höllentour, translated as Hell on Wheels, records 2003 from the perspective of Team Telekom. The film was directed by Pepe Danquart, who won an Academy Award for Live Action Short Film in 1993 for Black Rider (Schwarzfahrer).[71] Also released was Danish film Overcoming by Tómas Gislason, which records the 2004 Tour de France from the perspective of Team CSC.

Wired to Win : Surviving the Tour de France chronicles Française des Jeux riders Baden Cooke and Jimmy Caspar in 2003. By following their quest for the green jersey, won by Cooke, the film looks at the working of the brain. The film, made for IMAX theaters, appeared in December 2005. It was directed by Bayley Silleck, who was nominated for an Academy Award for Documentary Short Subject in 1996 for Cosmic Voyage.[72]

A fan, Scott Coady, followed the 2000 Tour with a handheld video camera. He made The Tour Baby! to benefit the Lance Armstrong Foundation, raising $160,000.[73]

Vive Le Tour by Louis Malle is an 18-minute short of 1962. The 1965 Tour was filmed by Claude Lelouch in Pour un Maillot Jaune. This 30-minute documentary has no narration and relies on sights and sounds of the Tour.

- Höllentour at IMDb

- Overcoming at IMDb

- Vive Le Tour at IMDb

- Wired to Win at IMDb

- Pour un Maillot Jaune at IMDb

In fiction, the 2003 animated feature Les Triplettes de Belleville (The Triplets of Belleville) ties into the Tour de France.

Amélie has clips from several Tours, including one in which a horse joins the peloton.

Doping

Allegations of doping have plagued the Tour almost since 1903. Early riders consumed alcohol and used ether, to dull the pain. Over the years they began to increase performance and the International Cycling Union (UCI) and governments enacted policies to combat the practice.

In 1924, Henri Pélissier and his brother Charles told the journalist Albert Londres they used strychnine, cocaine, chloroform, aspirin, "horse ointment" and other drugs.[74] The story was published in 'Le Petit Parisien' under the title Les Forçats de la Route ('The Convicts of the Road')[8][75][76][77]

On 13 July 1967, British cyclist Tom Simpson died climbing Mont Ventoux after taking amphetamine. In 1998, the "Tour of Shame", Willy Voet, soigneur for the Festina team, was arrested with erythropoietin (EPO), growth hormones, testosterone and amphetamine. Police raided team hotels and found products in possession of TVM. Riders went on strike. After mediation by director Jean-Marie Leblanc, police limited their tactics and riders continued. Some riders had abandoned and only 96 finished the race. In a 2000 trial, it became clear that management and health officials of the Festina team had organised the doping.

Further measures were introduced by race organizers and the UCI, including more frequent testing and tests for blood doping (transfusions and EPO use). A new, independent organization, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), was created. In 2002, the wife of Raimondas Rumšas, third in the 2002 Tour de France, was arrested after EPO and anabolic steroids were found in her car. Rumšas, who had not failed a test, was not penalised. In 2004, Philippe Gaumont said doping was endemic to his Cofidis team. Fellow Cofidis rider David Millar confessed to EPO after his home was raided. In the same year, Jesus Manzano, a rider with the Kelme team, alleged he had been forced by his team to use banned substances.[78]

Doping controversy has surrounded Lance Armstrong, although he has never been penalized. In August 2005, one month after Armstrong's seventh consecutive victory, L'Équipe claimed he had used EPO in the 1999 race.[79][80] Armstrong denied using EPO. At the same Tour, Armstrong's urine showed traces of a glucocorticosteroid hormone, although below the positive threshold. He said he had used skin cream containing triamcinolone to treat saddle sores.[81] Armstrong said he had received permission from the UCI to use this cream.[82]

The 2006 Tour had been plagued by the Operación Puerto doping case before it began, favorites such as Jan Ullrich and Ivan Basso banned by their teams a day before the start. Seventeen riders were implicated. Then the American rider Floyd Landis had a positive test for testosterone after he won stage 17; this was confirmed in his 'B' sample result, published on 5 August 2006. On 30 June 2008 Landis lost his appeal to the Court of Arbitration for Sport.[83]

On 24 May 2007, Erik Zabel admitted using EPO during the first week of the 1996 Tour,[84] when he won the maillot vert (green jersey). Following his plea that other cyclists admit to drugs, former winner Bjarne Riis admitted in Copenhagen on 25 May 2007 that he used EPO regularly from 1993 to 1998, including when he won the 1996 Tour.[85] His admission meant the top three in 1996 were all linked to doping, two admitting cheating.

On 24 July 2007 Alexander Vinokourov tested positive for a blood transfusion (Blood doping) after winning a time trial, prompting his Astana team to pull out and police to raid the team's hotel.[86] Next day Cristian Moreni tested positive for testosterone. His Cofidis team pulled out.[87]

The same day, leader Michael Rasmussen was removed for "violating internal team rules" by missing random tests on 9 May and 28 June. Rasmussen claimed to have been in Mexico. The Italian journalist Davide Cassani told Danish television he had seen Rasmussen in Italy. The alleged lying prompted his firing by Rabobank.[88]

On 11 July 2008 Manuel Beltrán tested positive for EPO after the first stage.[89]

On 17 July 2008, Ricardo Riccò tested positive for Continuous Erythropoiesis Receptor Activator (a variant of EPO),[90] after the fourth stage.

In October 2008, it was revealed that Ricco's teammate and Stage 10 winner Leonardo Piepoli, as well as Stefan Schumacher[91] - who won both time trials - and Bernhard Kohl[92] - 3rd of the General Classification and King of the Mountains - had been tested positive.

Deaths

- 1910: French racer Adolphe Helière drowned at the French Riviera during a rest day.

- 1935: Spanish racer Francisco Cepeda plunged down a ravine on the Col du Galibier.

- 1967: July 13, Stage 13: Tom Simpson died of heart failure during the ascent of Mont Ventoux. Amphetamines were found in Simpson's jersey and in blood.

- 1995: July 18, stage 15: Fabio Casartelli crashed at 88km/h (55 mph) descending the Col de Portet d'Aspet.

Another four fatal accidents have occurred.

- 1957: July 14, motorcycle rider Rene Wagter and passenger Alex Virot, a journalist for Radio-Luxembourg, went off a road in mountains near Ax-les-Thermes.

- 1958: An official, Constant Wouters, died after an accident with sprinter André Darrigade at the Parc des Princes.[93]

- 2000: A 12-year-old from Ginasservis known as Phillippe was hit by a car in the Tour de France publicity caravan.[94]

- 2002: A seven-year-old boy, Melvin Pompele, died near Retjons after running in front of the caravan.[94]

Statistics

One rider has won seven times:

- Lance Armstrong (

United States) in 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2005 (seven consecutive years).

United States) in 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, and 2005 (seven consecutive years).

Four riders have won five times:

- Jacques Anquetil (

France) in 1957, 1961, 1962, 1963 and 1964;

France) in 1957, 1961, 1962, 1963 and 1964; - Eddy Merckx (

Belgium) in 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972 and 1974;

Belgium) in 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972 and 1974; - Bernard Hinault (

France) in 1978, 1979, 1981, 1982 and 1985;

France) in 1978, 1979, 1981, 1982 and 1985; - Miguel Indurain (

Spain) in 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994 and 1995 (the first to do so in five consecutive years).

Spain) in 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994 and 1995 (the first to do so in five consecutive years).

Three riders have won three times:

- Philippe Thys (

Belgium) in 1913, 1914, and 1920;

Belgium) in 1913, 1914, and 1920; - Louison Bobet (

France) in 1953, 1954, and 1955;

France) in 1953, 1954, and 1955; - Greg LeMond (

United States) in 1986, 1989, and 1990.

United States) in 1986, 1989, and 1990.

Seven riders have won the Tour de France and the Giro d'Italia in the same year:

- Eddy Merckx (

Belgium) three times, in 1970, 1972, 1974

Belgium) three times, in 1970, 1972, 1974 - Fausto Coppi (

Italy) two times, in 1949, 1952

Italy) two times, in 1949, 1952 - Bernard Hinault (

France) two times, in 1982, 1985

France) two times, in 1982, 1985 - Miguel Indurain (

Spain) two times, in 1992, 1993

Spain) two times, in 1992, 1993 - Jacques Anquetil (

France) one time, in 1964

France) one time, in 1964 - Stephen Roche (

Ireland) one time, in 1987

Ireland) one time, in 1987 - Marco Pantani (

Italy) one time, in 1998

Italy) one time, in 1998

The youngest Tour de France winner was Henri Cornet (![]() France), aged 19 in 1904. Next youngest was Romain Maes (

France), aged 19 in 1904. Next youngest was Romain Maes (![]() Belgium), aged 21 in 1935.

Belgium), aged 21 in 1935.

The oldest winner was Firmin Lambot (![]() Belgium), aged 36 in 1922. Next oldest were Henri Pélissier (

Belgium), aged 36 in 1922. Next oldest were Henri Pélissier (![]() France) (1923) and Gino Bartali (

France) (1923) and Gino Bartali (![]() Italy) (1948), both 34.

Italy) (1948), both 34.

Gino Bartali holds the longest time span between titles, having earned his first and last Tour victories 10 years apart (in 1938 and 1948).

Riders from France have won most (36), followed by Belgium (18), Spain (11), United States (10), Italy (9), Luxembourg (4), Switzerland and the Netherlands (2 each) and Ireland, Denmark and Germany (1 each).

One rider has won the points competition six times:

- Erik Zabel (

Germany) 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2001 (consecutive years)

Germany) 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2001 (consecutive years)

One rider has been King of the Mountains seven times:

- Richard Virenque (

France) in 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1999, 2003 and 2004.

France) in 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1999, 2003 and 2004.

Two riders have been King of the Mountains six times:

- Federico Bahamontes (

Spain) in 1954, 1958, 1959, 1962, 1963, 1964

Spain) in 1954, 1958, 1959, 1962, 1963, 1964 - Lucien van Impe (

Belgium) in 1971, 1972, 1975, 1977, 1981, 1983

Belgium) in 1971, 1972, 1975, 1977, 1981, 1983

One rider has been King of the Mountains, won the points competition, and the Tour in the same year:

- Eddy Merckx (

Belgium) in 1969. Merckx would also have won the award for best young rider had it existed that competition was not initiated until 1975.

Belgium) in 1969. Merckx would also have won the award for best young rider had it existed that competition was not initiated until 1975.

The most appearances have been by Joop Zoetemelk (![]() Netherlands) with 16 and no abandonments. Three riders (Lucien van Impe (

Netherlands) with 16 and no abandonments. Three riders (Lucien van Impe (![]() Belgium), Guy Nulens (

Belgium), Guy Nulens (![]() Belgium) and Viatcheslav Ekimov (

Belgium) and Viatcheslav Ekimov (![]() Russia)) have made 15 appearances; van Impe and Ekimov finished all 15 whereas Nulens abandoned twice.

Russia)) have made 15 appearances; van Impe and Ekimov finished all 15 whereas Nulens abandoned twice.

In the early years of the Tour, cyclists rode individually, and were sometimes forbidden to ride together. This led to large gaps between the winner and the number two. Since the cyclists now tend to stay together in a peloton, the margins of the winner have become smaller, as the difference can only originate from time trials, breakaways or on mountain top finishes. In the table below, the ten smallest margins between the winner and the second placed cyclists at the end of the Tour are given.[95]

| Delay | Year | Opponents |

|---|---|---|

| 8" | 1989 | Greg LeMond - Laurent Fignon |

| 23" | 2007 | Alberto Contador - Cadel Evans |

| 32" | 2006 | Óscar Pereiro - Andreas Klöden |

| 38" | 1968 | Jan Janssen - Herman Van Springel |

| 40" | 1987 | Stephen Roche - Pedro Delgado |

| 48" | 1977 | Bernard Thévenet - Hennie Kuiper |

| 55" | 1964 | Jacques Anquetil - Raymond Poulidor |

| 58" | 2008 | Carlos Sastre - Cadel Evans |

| 1'01" | 2003 | Lance Armstrong - Jan Ullrich |

| 1'07" | 1966 | Lucien Aimar - Jan Janssen |

See also

- Giro d'Italia

- Vuelta a España

- List of Tour de France winners

- La Grande Boucle Féminine Internationale

- List of doping cases in cycling

Further reading

- Wheatcroft, Geoffrey (2004) [2005]. Le Tour: A History of the Tour de France, 1903-2003. Simon & Schuster UK. ISBN 0684028794.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - McGann, Bill (2006) [2006]. The Story of the Tour De France. Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 1598581805.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Delanzy, Eric (2006) [2006]. Inside the Tour de France: The Pictures, the Legends, and the Untold Stories. Rodale Books. ISBN 1594862303.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Directory of races and Jersey winners - 1903-2010

Notes

- ^ "C’était en 1913. J’étais leader du classement général. Une nuit, Desgrange rêva d’un maillot couleur or et me proposa de le porter. Je refusais, car je me sentais déjà le point de mire de tous. Il insista, mais je me montrais intraitable. Têtu, H.D. revint à la charge par la tangente. En effet, quelques étapes plus loin, ce fut mon directeur sportif de la marque Peugeot, M. Baugé, qui me conseilla de céder. On acheta donc dans le premier magasin venu, un maillot jaune. Il était juste aux dimensions nécessaires. Trop juste même, puisqu’il fallut découper une encolure plus grande pour le passage de la tête et c’est ainsi que je fis plusieurs étapes en décolleté de grande dame. Ce qui ne m’empêcha pas de gagner mon premier Tour!"

- ^ A school book written by Augustine Fouillée under the name G. Bruno and published in 1877, it sold six million by 1900, seven million by 1914 and 8,400,000 by 1976. It was used in schools until the 1950s and is still available.

- ^ In times of Empire, and when Algeria was considered not a colony but part of France, there was a tendency to see France as not just metropolitan France but all its colonies as well. The popular description of France as "the hexagon" wasn't created by the Tour de France but the Tour de France accelerated the process, say Boeuf and Léonard

References

- ^ name="ASO">"Regulations of the race" (PDF). ASO/letour.fr. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ a b c d "Tour Honour Roll", Ride Media 2007 Official Tour de France Guide, Australian Edition: 172, 200–201, 2007 Cite error: The named reference "tourlength" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Coyle, Daniel (2006-07-16), "What He's Been Pedaling", New York Times Magazine

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Boeuf, Jean-Luc, and Léonard, Yves (2003), La République du Tour de France, Seuil, France, p23

- ^ Nicholson, Geoffrey (1991) Le Tour, the rise and rise of the Tour de France, Hodder and Stoughton, UK

- ^ Boeuf, Jean-Luc and Léonard, Yves (2003); La République de Tour de France, Seuil, France

- ^ Woodland, Les (2000), The Unknown Tour de France, Cycling Resources, USA, p23

- ^ a b c d e f g Woodland, Les (2003). The Yellow Jersey Companion to the Tour de France. London: Yellow Jersey Press.

- ^ Woodland, Les (2000), The Unknown Tour de France, Cycle Resources, USA, p28

- ^ "BBC History of the Tour de France: 1903-1914: Pioneers and 'assassins'". BBC Sport. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ "Torelli's History of the Tour de France: the 1930s or, All They Wanted To Do Was to Sell a Few More Newspapers". BikeRaceInfo.com. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- ^ Woodland, Les (2000), The Unknown Tour de France, Cycling Resources, USA, p38

- ^ Ibid.,Moore, p.108

- ^ Woodland, Les (2000), The Unknown Tour de France, Cycling Resources, USA, p43

- ^ Seray, Jacques (1994), 1904, The Tour de France which as to be the last, Buonpane Publications, USA

- ^ Professional Cycling Palmarès Site | Tour de France: 1924

- ^ McGann, Bill and Carol (2006), The Story of the Tour de France, Dogear, USA

- ^ Augendre, Jacques (1996), Le Tour de France, Panorama d'un Siècle, Société du Tour de France, France, p7

- ^ Augendre, Jacques (1996), Le Tour de France, Panorama d'un Siècle, Société du Tour de France, France, 9

- ^ Augendre, Jacques (1996), Le Tour de France, Panorama d'un Siècle, Société du Tour de France, France, p13

- ^ Maso, Benjamin (2003), Het Zweet der Goden, , Atlas, Netherlands, p50

- ^ McGann, Bill and Carol (2006), The Story of the Tour de France, Dog Ear, USA, p84

- ^ a b Augendre, Jacques (1996), Le Tour de France, Panorama d'un Siècle, p30

- ^ Tour de France, 100 ans, 1903-2003, L’Équipe, France, 2003, p182

- ^ Augendre, Jacques (1996), Le Tour de France, Panorama d'un Siècle, Société du Tour de France, France, p55

- ^ Maso, Benjamin (2003), Het Zweet der Goden, Atlas, Netherlands, p112

- ^ Augendre, Jacques (1996), Le Tour de France; Panorama d'un Siècle, Société du Tour de France, France, p55

- ^ Augendre, Jacques (1996), Le Tour de France; Panorama d'un Siècle, Société du Tour de France, France, p59

- ^ Nicholson, Geoffrey (1991), Le Tour, Hodder and Stoughton, UK, p50

- ^ Augendre, Jacques (1996), Le Tour de France; Panorama d'un Siècle, Société du Tour de France, France, p60

- ^ Maso, Benjamin (2003), Het Zweet der Goden, Atlas, Netherlands, p126

- ^ Nicholson, Geoffrey (1991), Le Tour, Hodder and Stoughton, UK, ISBN 0340542683, p14

- ^ Woodland, Les (2007), Yellow Jersey Guide to the Tour de France, Yellow Jersey, UK, ISBN 9780224080163 p234

- ^ a b Nicholson, Geoffrey (1991), Le Tour, Hodder and Stoughton, UK, ISBN 0340542683, p14

- ^ Augendre, Jacques (1996), Le Tour de France; Panorama d'un Siècle, Société du Tour de France, France, p62

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Goddet, Jacques (1991) L'Équipée Belle, Robert Laffont, France

- ^ Tour de France, 100 ans, 1903-2003, L’Équipe, France, 2003, p227

- ^ McGann, Bill and Carol McGann, The Story of the Tour de France:1903-1964|origyear=2006|url=http://books.google.nl/books?id=jxq20JskqMUC%7Caccessdate=2008-07-02%7Cpublisher=Dog Ear Publishing|isbn=1598581805}}

- ^ Boeuf, Jean-Luc and Léonard, Yves (2003), La République du Tour de France, Seuil, France

- ^ Libération, France, 4 July 2003.

- ^ Cycling Revealed - Tour de France Timeline

- ^ Dauncey, Hugh (2003) [2003]. The Tour de France, 1903-2003: A Century of Sporting Structures, Meanings and Values. Routledge. ISBN 0714653624. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Augendre, Jacques (1996), Le Tour de France, Panorama d'un Siècle, Société du Tour de France, p69

- ^ "Tour de France Letters Special - July 23, 2004". CyclingNews. 2004-07-23. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Maloney, Tim (2004-07-21). "Stage 16 - July 21: Bourg d'Oisans - Alpe d'Huez ITT, 15.5 km; Sign of the times: Armstrong dominates on l'Alpe d'Huez". CyclingNews. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Provence Blog by ProvenceBeyond: Tour de France starting in Monaco". Provenceblog.typepad.com. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ Woodland, Les (2003). The Yellow Jersey Companion to the Tour de France. London: Yellow Jersey Press. pp. 300–304.

- ^ a b c Template:PDFlink pp. 21-25

- ^ Augendre, Jacques: Tour de France, panorama d'un siècle, Soc. du Tour de France, 1996, p19

- ^ a b Chany, Pierre (1997) La Fabuleuse Histoire du Tour de France, Ed. de la Martinière, France.

- ^ Chany, Pierre: La Fabuleuse Histoire de Cyclisme, Nathan, France

- ^ Augendre, Jacques: Tour de France, panorama d'un siècle, Soc. du Tour de France, 1996

- ^ a b c Woodland, Les (2007), Yellow Jersey Guide to the Tour de France, Yellow Jersey, UK, ISBN 9780224080163, p96

- ^ a b Woodland, Les (2007), Yellow Jersey Guide to the Tour de France, Yellow Jersey, UK, ISBN 9780224080163, p202

- ^ a b c Woodland, Les (2007), Yellow Jersey Guide to the Tour de France, Yellow Jersey, UK, ISBN 9780224080163, p203

- ^ Thompson, Christopher S. (2006). The Tour de France. University of California Press. p. p40. ISBN 0520247604.

{{cite book}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ Augendre, Jacques, (1996), Le Tour de France, Panorama d'un Siècle, Société du Tour de France, France, p45

- ^ "The Tour de France" (website). BBC H2G2. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- ^ "2006 Regulations of the Race and Prize Money" (PDF). Tour de France regulations. Amaury Sport Organisation. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- ^ "Tour de France Facts, Figures and Trivia". Gofrance.about.com. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ^ Cited Ollivier, Jean-Paul (2001) L'ABCdaire du Tour de France, Flammarion, France

- ^ a b Boeuf, Jean-Luc and Léonard, Yves (2003), La République du Tour de France, Seuil, France, p67

- ^ L'image d'une France unifiée par le sol, Vigarello, Georges, Le Tour de France, p3807, cited Boeuf, Jean-Luc and Léonard, Yves (2003), La République du Tour de France, Seuil, France, p67

- ^ France Since 1871: Lecture 9 Transcript, by John M. Merriman, Open Yale Courses, October 3, 2007.

- ^ Boeuf, Jean-Luc and Léonard, Yves (2003), La République du Tour de France, Seuil, France, p70

- ^ Boeuf, Jean-Luc and Léonard, Yves (2003), La République du Tour de France, Seuil, France, p74

- ^ a b Boeuf, Jean-Luc and Léonard, Yves (2003), La République du Tour de France, Seuil, France, p75-76

- ^ Le Monde, 16 April 2002, supplement page 3

- ^ Boeuf, Jean Luc and Léonard Yves (2003), La République du Tour de France, Seuil, France

- ^ Chris Jones, Kraftwerk, Tour De France Soundtracks, BBC, August 4, 2003

- ^ "Blood, sweat and gears". Sydney Morning Herald. 2005-05-27. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ ""Wired" is winning tour of race, brain". BOSTON GLOBE. 2005-12-30. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Melvin, Ian (2004-10-08). "The Tour Baby!". RoadCycling.com. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Tour de France, 100 ans, 1903-2003, L’Équipe, France 2003, p149

- ^ De Mondenard, Dr Jean-Pierre: Dopage, l'imposture des performances, Chiron, France, 2000

- ^ Association of British Cycling Coaches (ABCC), Drugs and the Tour De France by Ramin Minovi

- ^ Moore, Tim, "French Revolutions: Cycling the Tour de France",[St Martin Press, NY 2001],p.145

- ^ "Ex-Kelme rider promises doping revelations". VeloNews. 2004-03-20. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ L'Équipe, France, 23 August 2005, p1

- ^ "L'Équipe alleges Armstrong samples show EPO use in 99 Tour". VeloNews. 2005-08-23. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Armstrong's journey : Tour leader rides from Texas plains to Champs-Elysees". CNN Sports Illustrated. 2000-07-22. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Armstrong, Lance (2000). It's not about the bike: My journey back to life. New York: Penguin Putnam.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Landis loses appeal, must forfeit Tour de France title". Houston Chronicle. 2008-06-30. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Westemeyer, Susan (2007-05-24). "Zabel and Aldag confess EPO usage". CyclingNews. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Riis, Tour de France Champ, Says He Took Banned Drugs". Bloomberg.com. 2007-05-25. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ ABCnews.go.com - Astana team pulls out of Tour de France

- ^ BBC.co.uk - Tour hit by second doping result

- ^ - Rasmussen, Tour de France Leader, Is Expelled by Team

- ^ "Doping agency: Beltran positive for EPO". google.com. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|agancy=ignored (help)[dead link] - ^ "BBC SPORT | Other sport... | Cycling | Tour 'winning war against doping'". News.bbc.co.uk. Page last updated at 18:30 GMT, Thursday, 17 July 2008 19:30 UK. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Piepoli and Schumacher Tour de France samples positive for CERA

- ^ Kohl positive confirmed

- ^ Woodland, Les (2003). The Yellow Jersey Companion to the Tour de France. London: Yellow Jersey Press. p. 105.

- ^ a b Woodland, Les (2003). The Yellow Jersey Companion to the Tour de France. London: Yellow Jersey Press. p. 80.

- ^ "Verschil tussen de nummers 1 en 2 van het eindklassement" (in Dutch). www.tourde-france.nl. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

External links

- Tour de France Official Website

- 2009 Fifth leg in Perpignan.

- 2008 Tour de France Route and Street View Images using Google Maps[dead link]

- RoadCycling.com - Tour de France news, results, rider diaries and photos

- Template:PDFlink

- Tour de France race news from Bicycling Magazine

- Cyclingfans.com Tour de France live video and audio feeds

- VeloNews Tour de France race coverage

- TourdeFrance.net - Tour de France Photos, Route & Statistics

- Cyclingpost.com Tour de France

- Interactive map Tour de France New Google Map with terrain view of all the stages in the Tour de France 2008

- Le dico du Tour / Le Tour de France de 1947 à 2008 (French)

- Bikemap: Tour de France 2008: all stages on a map with elevation profile

- Past winners of the Tour and their Bicycles

- Radio France International dossier on Tour de France 2008: daily audio reports