Vestal Virgin

In Ancient Rome, the Vestal Virgins (sacerdos Vestalis), were the virgin holy female priests of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth. Their primary task was to maintain the sacred fire of Vesta. The Vestal duty brought great honor and afforded greater privileges to women who served in that role. They were the only female priests within the Roman religious system.

In mythology, the infamous Tarpeia, daughter of Spurius Tarpeius, was a traitorous Vestal Virgin. Rhea Sylvia, who was raped by Mars and conceived Romulus and Remus, and Tuccia, whose chastity was questioned, were sometimes accounted prototypes of Vestal Virgins.

The discovery of a "House of the Vestals" in Pompeii made the Vestal Virgins a popular subject in the 18th century and the 19th century.

The objects of the cult were essentially the hearth fire and pure water drawn into a clay vase.

History

Plutarch attributes the founding of the Temple of Vesta to Numa Pompilius, who appointed at first two priestesses to which were added another two with Servius raising the total to six.[1] Ambrose alludes to a seventh towards the end of the pagan era[2]. The second century Roman antiquarian Aulus Gellius writes that the first vestal virgin taken from her parents was led away in hand by Numa Pompilius. Numa also appointed the Pontifex Maximus to preside over rites, prescribe rules for public ceremony, and watch over the Vestals. The first Vestals, according to Varro, were Gegania, Veneneia, Canuleia, and Tarpeia. [Grimm, 275].

The Vestal Virgins became a powerful and influential force in the Roman state. When the dictator Sulla included the young Julius Caesar on his death list of political opponents the Vestals interceded on Caesar's behalf and gained him pardon. [3] Augustus included the Vestals in all major dedications and ceremonies.

The Chief Vestal (Virgo Vestalis Maxima) oversaw the efforts of the Vestals, and was present in the Collegium Pontificum. Chief Vestal Occia presided over the Vestals for 57 years, according to Tacitus. The last known Chief Vestal was Coelia Concordia in 380. The College of Vestal Virgins ended in 394, when the fire was extinguished and the Vestal Virgins disbanded by order of Theodosius I.

The Order of the Vestal Virgins and its well-being was considered to have a direct bearing on the health and prosperity of the city. The prefect Symmachus wrote:

The laws of our ancestors provided for the Vestal virgins and the ministers of the gods a moderate maintenance and just privileges. This gift was preserved inviolate till the time of the degenerate moneychangers, who diverted the maintenance of sacred chastity into a fund for the payment of base porters. A public famine ensued on this act, and a bad harvest disappointed the hopes of all the provinces... it was sacrilege which rendered the year barren, for it was necessary that all should lose that which they had denied to religion.[4]

Zosimus records[5] how the Christian noblewoman Serena, niece of Theodosius I, entered the temple and took from the statue of the goddess a necklace and placed it on her own neck. An old woman appeared, the last of the Vestal Virgins, who proceeded to rebuke Serena and called down upon her all just punishment for her act of impiety.[6] According to Zosimus, Serena was then subject to dreadful dreams predicting her own untimely death. Augustine would be inspired to write The City of God in response to murmurings that the capture of Rome and the disintegration of its empire was due to the advent of the Christian era and its intolerance of the old gods who had defended the city for over a thousand years.

Terms of service

The Vestal Virgins were committed to the priesthood at a young age (before puberty) and were sworn to celibacy for a period of 30 years. These 30 years were, in turn, divided into three periods of a decade each: ten as students, ten in service, and ten as teachers. Afterwards, they could marry if they chose to do so.[7] However, few took the opportunity to leave their respected role in very luxurious surroundings. This would have required them to submit to the authority of a man, with all the restrictions placed on women by Roman law. On the other hand, a marriage to a former Vestal Virgin was highly honoured.

Selection

The high priest (Pontifex Maximus) chose by lot from a group of young girl candidates between their sixth and tenth year. To obtain entry into the order they were required to be free of physical and mental defects, have two living parents and to be a daughter of a free born resident in Italy.

To replace a Vestal who had died, candidates would be presented in the quarters of the Chief Vestal for the selection of the most virtuous. Tacitus (Annals ii.30,86) recounts how Gaius Fonteius Agrippa and Domitius Pollio offered their daughters as Vestal candidates in AD 19 to fill such a vacant position. Equally matched, Pollio's daughter was chosen only because Agrippa had been recently divorced. The Pontifex Maximus (Tiberius) "consoled" the failed candidate with a dowry of 1 million sesterces ($5 million).

Once chosen they left the house of their father, were inducted by the Pontifex Maximus, and their hair was shorn. The high priest pointed to his choice with the words, "I take you, Amata, to be a Vestal priestess, who will carry out sacred rites which it is the law for a Vestal priestess to perform on behalf of the Roman people, on the same terms as her who was a Vestal on the best terms".[8] Now they were under the protection of the goddess. Later, as it became more difficult to recruit Vestals, plebeian girls were admitted, then daughters of freed men[9] (Young, Worsfold, 21-3).

Tasks

Their tasks included the maintenance of the fire sacred to Vesta, the goddess of the hearth and home, collecting water from a sacred spring, preparation of food used in rituals and caring for sacred objects in the temple's sanctuary.[10] By maintaining Vesta's sacred fire, from which anyone could receive fire for household use, they functioned as "surrogate housekeepers", in a religious sense, for all of Rome. Their sacred fire was treated, in Imperial times, as the Emperor's household fire.

The Vestals were put in charge of keeping safe the wills and testaments of various people such as Caesar and Mark Antony. In addition, the Vestals also guarded some sacred objects, including the Palladium, and made a special kind of flour called mola salsa which was sprinkled on all public offerings to a god.

Privileges

The dignities accorded to the Vestals were significant.

- in an era when religion was rich in pageantry, the presence of the College of Vestal Virgins was required in numerous public ceremonies and wherever they went, they were transported in a carpentum, a covered two-wheeled carriage, preceded by a lictor, and had the right-of-way;

- at public games and performances they had a reserved place of honor;

- unlike most Roman women, they were not subject to the patria potestas and so were free to own property, make a will, and vote;

- they gave evidence without the customary oath;

- they were, on account of their incorruptible character, entrusted with important wills and state documents, like public treaties;

- their person was sacrosanct: death was the penalty for injuring their person and their escorts protected anyone from assault;

- they could free condemned prisoners and slaves by touching them - if a person who was sentenced to death saw a vestal virgin on his way to the execution, he was automatically pardoned.

- they were allowed to throw ritual straw figurines called Argei, into the Tiber on May 15.[11][12]

Punishments

Allowing the sacred fire of Vesta to die out, suggesting that the goddess had withdrawn her protection from the city, was a serious offense and was punishable by scourging.[13] The chastity of the Vestal Virgins was considered to have a direct bearing on the health of the Roman state. When they became Vestal Virgins they left behind the authority of their fathers and became daughters of the state. Any sexual relationship with a citizen was therefore considered to be incest and an act of treason.[14] The punishment for violating the oath of celibacy was to be buried alive in the Campus Sceleratus or "Evil Fields" (an underground chamber near the Colline gate) with a few days of food and water.

Ancient tradition required that a disobedient Vestal Virgin be buried within the city, that being the only way to kill her without spilling her blood, which was forbidden. However, this practice contradicted the Roman law, that no person may be buried within the city. To solve this problem, the Romans buried the offending priestess with a nominal quantity of food and other provisions, not to prolong her punishment, but so that the Vestal would not technically die in the city, but instead descend into a "habitable room" (Staples 152). Moreover, she would die willingly. Cases of unchastity and its punishment were rare.[15] The Vestal Tuccia was accused of fornication, but she carried water in a sieve to prove her chastity.

O Vesta, if I have always brought pure hands to your secret services, make it so now that with this sieve I shall be able to draw water from the Tiber and bring it to Your temple (Vestal Virgin Tuccia in Valerius Maximus 8.1.5 absol).

Because a Vestal's virginity was thought to be directly correlated to the sacred burning of the fire, if the fire were extinguished it might be assumed that either the Vestal had acted wrongly or that the Vestal had simply neglected her duties. The final decision was the responsibility of the Pontifex Maximus, or the head of the pontifical college, as opposed to a judicial body (Staples 152) [dubious – discuss]. While the order of the Vestal Virgins was in existence for over one thousand years there are only ten recorded convictions for unchastity and these trials all took place at times of political crisis for the Roman state. It has been suggested[16] that Vestal Virgins were used as scapegoats[17] in times of great crisis. (Staples 138).

The earliest Vestals at Alba Longa were said to have been whipped to death for having sex. The Roman king Tarquinius Priscus instituted the punishment of live burial, which he inflicted on the priestess Pinaria. But whipping with rods sometimes preceded the immuration, as was done to Urbinia in 471 BC. [Worsfold, 62].

Suspicions first arose against Minucia through an improper love of dress and the evidence of a slave. She was found guilty of unchastity and buried alive.[18] Similarly Postumia, who though innocent according to Livy[19] was tried for unchastity with suspicions being aroused through her immodest attire and less than maidenly manner. Postumia was sternly warned "to leave her sports, taunts and merry conceits,". Aemilia, Licinia, and Martia were executed after being denounced by the servant of a barbarian horseman. A few Vestals were acquitted. Some cleared themselves through ordeals [13].

The paramour of a guilty Vestal was whipped to death in the Forum Boarium or on the Comitium.[20]

Vestal festivals

The chief festivals of Vesta were the Vestalia celebrated June 7 until June 15. On June 7 only, her sanctuary (which normally no one except her priestesses, the Vestal Virgins, entered) was accessible to mothers of families who brought plates of food. The simple ceremonies were officiated by the Vestals and they gathered grain and fashioned salty cakes for the festival. This was the only time when they themselves made the mola salsa, for this was the holiest time for Vesta, and it had to be made perfectly and correctly, as it was used in all public sacrifices.

Clothing

The main articles of their clothing consisted of an infula, a suffibulum and a palla. The infula was a long headdress that draped over the shoulders. Usually found underneath were red and white woolen ribbons. The suffibulum was the brooch that clipped the palla together. The palla was a simple mantle, wrapped around the Vestal Virgin. The brooch and mantle were draped over the left shoulder.

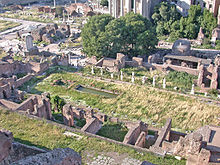

House of the Vestals

The House of the Vestals was the residence of the Vestal priestesses in Rome. Behind the Temple of Vesta (which housed the sacred fire), the Atrium Vestiae was a three-story building at the foot of the Palatine Hill.

List of well-known Vestal Virgins

Pre-Roman and Early Roman Vestals

Early Roman and Pre-Roman Vestals were rarely named in Roman histories. Among them were:

- Rhea Silvia, a possibly mythical mother of Rome's founders.

- Tarpeia, who betrayed Rome to the Sabines, and for whom the Tarpeian Rock is named.

- Aemilia, who, when the sacred fire was extinguished on one occasion, prayed to Vesta for assistance, and miraculously rekindled it by throwing a piece of her garment upon the extinct embers.[21][22]

Late Republican Vestals

In the Late Republic, Vestals became more notorious, accused either of unchastity or marrying notorious demagogues.

- Aemilia (d. 114 BC), who was put to death in 114 BC for having committed incest on several occasions. She induced two of the other vestal virgins, Marcia and Licinia, to commit the same crime, but these two were acquitted by the pontifices when Aemilia was condemned, but were subsequently condemned by the praetor L. Cassius.[23][24][25][26]

- Licinia (d. 114 BC-113 BC), condemned in 113 BC or 114 BC by the famous jurist Lucius Cassius Longinus Ravilla (consul 127 BC) along with Marcia and Aemilia, for unchastity.

- Fabia, Chief Vestal (b ca 98-97 BC; fl. 50 BC), admitted to the order in 80 BC[27], half-sister of Terentia (Cicero's first wife), and a wife of Dolabella who later married her niece Tullia; she was probably mother of the later consul of that name.

- Licinia (flourished 1st century BC), who was courted by her kinsman triumvir Marcus Licinius Crassus who wanted her property. This relationship gave rise to rumors. Plutarch says: "And yet when he was further on in years, he was accused of criminal intimacy with Licinia, one of the vestal virgins and Licinia was formally prosecuted by a certain Plotius. Now Licinia was the owner of a pleasant villa in the suburbs which Crassus wished to get at a low price, and it was for this reason that he was forever hovering about the woman and paying his court to her, until he fell under the abominable suspicion. And in a way it was his avarice that absolved him from the charge of corrupting the vestal, and he was acquitted by the judges. But he did not let Licinia go until he had acquired her property." [28] Licinia became a Vestal Virgin in 85 BC and remained a Vestal until 61 BC.[27]

Early Imperial Vestals

Late Imperial Vestals

- Aquilia Severa, whom Emperor Elagabalus married amid considerable scandal.

- Coelia Concordia, the last head of the order.

Further reading

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898)

- Parker, Holt N. "Why Were the Vestals Virgins? Or the Chastity of Women and the Safety of the Roman State", American Journal of Philology, Vol. 125, No. 4. (2004), pp. 563–601.

- Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome

- Wildfang, Robin Lorsch. Rome's Vestal Virgins. Oxford: Routledge, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0-415-39795-2; paperback, ISBN 0-415-39796-0).

External links

- Rodolfo Lanziani (1898) "The Fall of a Vestal" Chapter 6, in Ancient Rome in the Light of Recent Discoveries. Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston and New York, 1898.

References

- ^ "Life of Numa Pompilius" 9.5-10, 2nd cent A.D.[1]

- ^ "Letter to Emperor Valentianus", Letter #18, Ambrose.[2]

- ^ Suetonius, "Julius Caesar", 1.2

- ^ "The Letters of Ambrose", The Memorial of Symmachus.[3]

- ^ "The New History", 5:38, Zosimus.[4]

- ^ "The Curse of the Last Vestal", Melissa Barden Dowling, Biblical Archaeology Society, Archaeology Odyssey, Jan/Feb 2001 4:01.

- ^ "Life of Numa Pompilius", Plutarch, 9.5-10, 2nd century A.D.[5]

- ^ "Vestal Virgins", Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights 1.12.[6]

- ^ "Vestal Virgins", Encyclopedia Britannica, Ultimate Reference DVD, 2003.

- ^ "Vestal Virgins", Encyclopedia Britannica, Ultimate Reference Suite, 2003.

- ^ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, i.19, 38.[7]

- ^ William Smith, "A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities", John Murray, London, 1875.[8]

- ^ "Vesta", Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911 Edition.[9]

- ^ "Vestal Virgins - Chaste Keepers of the Flame", Melissa Barden Dowling, Biblical Archaeological Society, Archaeology Odyssey, Jan/Feb 2001 4:01.

- ^ "Vesta", Encyclopedia Britannica 1911 Edition.[10]

- ^ "Vestal Virgins - Chaste Keepers of the Flame", Melissa Barden Dowling, Biblical Archaeological Society, Archaeology Odyssey, Jan/Feb 2001 4:01.

- ^ Since the health of City was perceived in some way to be linked to the purity and spiritual health of the Vestals suspicions may have been fuelled in times of trouble. The allusions to a possible scapegoat could have been reinforced by the Vestals throwing Argei into the Tiber each year on May 15. cf. "Religion of Ancient Rome", C.C Martindale, Studies in Comparative Religion, CTS, Vol 2, 14:7

- ^ "History of Rome", Book 8.15, Livy.[11]

- ^ "History of Rome", Book 4.44, Livy.[12]

- ^ Howatson M. C.: Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, Oxford University Press, 1989, ISBN 0-19-866121-5

- ^ Dionys. ii. 68

- ^ Valerius Maximus, i. 1. §7

- ^ Plutarch, Quaest. Rom. p. 284

- ^ Livy, Epit. 63

- ^ Orosius, v. 15

- ^ Ascon. in Cic. Mil. p. 467 ed. Orelli

- ^ a b List of Vestal Virgins

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Crassus