Prostate

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2008) |

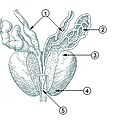

| Prostate | |

|---|---|

Male Anatomy | |

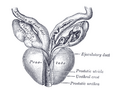

Prostate with seminal vesicles and seminal ducts, viewed from in front and above. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Endodermic evaginations of the urethra |

| Artery | internal pudendal artery, inferior vesical artery, and middle rectal artery |

| Vein | prostatic venous plexus, pudendal plexus, vesicle plexus, internal iliac vein |

| Nerve | inferior hypogastric plexus |

| Lymph | external iliac lymph nodes, internal iliac lymph nodes, sacral lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | prostata |

| MeSH | D011467 |

| TA98 | A09.3.08.001 |

| TA2 | 3637 |

| FMA | 9600 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The prostate (from Greek προστάτης - prostates, literally "one who stands before", "protector", "guardian"[1]) is a compound tubuloalveolar exocrine gland of the male mammalian reproductive system. Females also have prostate glands, previously called paraurethral or Skene's glands, connected to the distal third of the urethra in the prevaginal space.

The prostate differs considerably among species anatomically, chemically, and physiologically.

Function

The function of the prostate is to store and secrete a slightly alkaline (pH 7.29) fluid, milky or white in appearance,[2] that usually constitutes 25-30% of the volume of the semen along with spermatozoa and seminal vesicle fluid. The alkalinity of semen helps neutralize the acidity of the vaginal tract, prolonging the lifespan of sperm. The alkalinization of semen is primarily accomplished through secretion from the seminal vesicles.[3] The prostatic fluid is expelled in the first ejaculate fractions together with most of the spermatozoa. In comparison with the few spermatozoa expelled together with mainly seminal vesicular fluid those expelled in prostatic fluid have better motility, longer survival and better protection of the genetic material (DNA).

The prostate also contains some smooth muscles that help expel semen during ejaculation.

Secretions

Prostatic secretions vary among species. They are generally composed of simple sugars, and are often slightly alkaline.

In human prostatic secretions, the protein content is less than 1% and includes proteolytic enzymes, prostatic acid phosphatase, and prostate-specific antigen. The secretions also contain zinc with a concentration 500-1,000 times the concentration in blood.

Regulation

To work properly, the prostate needs male hormones (androgens), which are responsible for male sex characteristics.

The main male hormone is testosterone, which is produced mainly by the testicles. Some male hormones are produced in small amounts by the adrenal glands. However, it is dihydrotestosterone that regulates the prostate.

Development

The prostatic part of the urethra develops from the pelvic (middle) part of the urogenital sinus (endodermal origin). Endodermal outgrowths arise from the prostatic part of the urethra and grow into the surrounding mesenchyme. The glandular epithelium of the prostate differentiates from these endodermal cells, and the associated mesenchyme differentiates into the dense stroma and the smooth muscle of the prostate. [4] The prostate glands represent the modified wall of the proximal portion of the male urethra and arises by the 9th week of embryonic life in the development of the reproductive system. Condensation of mesenchyme, urethra and Wolffian ducts gives rise to the adult prostate gland, a composite organ made up of several glandular and non-glandular components tightly fused within a common capsule.

Female prostate gland

The Skene's gland, also known as the paraurethral gland, found in females, is homologous to the prostate gland in males. In 2002, the Skene's gland, was officially renamed the prostate by the Federative International Committee on Anatomical Terminology.[5]

The female prostate, like the male prostate, secretes PSA and levels of this antigen rise in the presence of carcinoma of the gland. The gland also expels fluid, like the male prostate, during orgasm.[6] Researchers argue that the organ should therefore be called a female prostate and not "Skene's gland".[7]

Structure

A healthy human prostate is slightly larger than a walnut. It surrounds the urethra just below the urinary bladder and can be felt during a rectal exam.

The ducts are lined with transitional epithelium.

Within the prostate, the urethra coming from the bladder is called the prostatic urethra and merges with the two ejaculatory ducts. (The male urethra has two functions: to carry urine from the bladder during urination and to carry semen during ejaculation.) The prostate is sheathed in the muscles of the pelvic floor, which contract during the ejaculatory process.

The prostate can be divided in two different ways: by zone, or by lobe.[8]

Zones

The "zone" classification is more often used in pathology.

The prostate gland has four distinct glandular regions, two of which arise from different segments of the prostatic urethra:

| Name | Percent | Description |

| Peripheral zone (PZ) | Composes up to 70% of the normal prostate gland in young men | The sub-capsular portion of the posterior aspect of the prostate gland which surrounds the distal urethra. It is from this portion of the gland that more than 64% of prostatic cancers originate. |

| Central zone (CZ) | Constitutes approximately 25% of the normal prostate gland | This zone surrounds the ejaculatory ducts. The central zone accounts for roughly 2.5% of prostate cancers although these cancers tend to be more aggressive and more likely to invade the seminal vesicles.[9] |

| Transition zone (TZ) | Responsible for 5% of the prostate volume at puberty. | Prostate cancer originates in this zone in roughly 34% of patients. The transition zone surrounds the proximal urethra and is the region of the prostate gland which grows throughout life and is responsible for the disease of benign prostatic enlargement. (2) |

| Anterior fibro-muscular zone (or stroma) | Accounts for approximately 5% of the prostatic weight | This zone is usually devoid of glandular components, and composed only, as its name suggests, of muscle and fibrous tissue. |

Lobes

The "lobe" classification is more often used in anatomy.

| Anterior lobe (or isthmus) | roughly corresponds to part of transitional zone |

| Posterior lobe | roughly corresponds to peripheral zone |

| Lateral lobes | spans all zones |

| Median lobe (or middle lobe) | roughly corresponds to part of central zone |

Prostate disorders

Prostatitis

Prostatitis is inflammation of the prostate gland. There are different forms of prostatitis, each with different causes and outcomes. Acute prostatitis and chronic bacterial prostatitis are treated with antibiotics; chronic non-bacterial prostatitis or male chronic pelvic pain syndrome, which comprises about 95% of prostatitis diagnoses, is treated by a large variety of modalities including alpha blockers, phytotherapy, physical therapy, psychotherapy, antihistamines, anxiolytics, nerve modulators and more.[10] More recently, a combination of trigger point and psychological therapy has proved effective as well.[11]

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) occurs in older men;[12] the prostate often enlarges to the point where urination becomes difficult. Symptoms include needing to go to the toilet often (frequency) or taking a while to get started (hesitancy). If the prostate grows too large it may constrict the urethra and impede the flow of urine, making urination difficult and painful and in extreme cases completely impossible.

BPH can be treated with medication, a minimally invasive procedure or, in extreme cases, surgery that removes the prostate. Minimally invasive procedures include Transurethral needle ablation of the prostate (TUNA) and Transurethral microwave thermotherapy (TUMT).[13] These outpatient procedures may be followed by the insertion of a temporary Prostatic stent, to allow normal voluntary urination, without exacerbating irritative symptoms[14].

The surgery most often used in such cases is called transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP or TUR). In TURP, an instrument is inserted through the urethra to remove prostate tissue that is pressing against the upper part of the urethra and restricting the flow of urine. Older men often have corpora amylacea[15] (amyloid), dense accumulations of calcified proteinaceous material, in the ducts of their prostates. The corpora amylacea may obstruct the lumens of the prostatic ducts, and may underlie some cases of BPH.

Urinary frequency due to bladder spasm, common in older men, may be confused with prostatic hyperplasia. Statistical observations suggest that a diet low in fat and red meat and high in protein and vegetables, as well as regular alcohol consumption, could protect against BPH.[16]

Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers affecting older men in developed countries and a significant cause of death for elderly men (estimated by some specialists at 3%). Regular rectal exams, as well as measurement of Prostate Specific Antigen are recommended for older men, usually ages 50 and up to detect prostate cancer early.

Male sexual response

During orgasm, sperm is transmitted from the ductus deferens into the male urethra via the ejaculatory ducts, which lie within the prostate gland. The prostate is sometimes referred to as the "male G-spot". Some men are able to achieve orgasm solely through stimulation of the prostate gland, such as prostate massage or receptive anal intercourse. Men who report the sensation of prostate stimulation often give descriptions similar to female's accounts of G-spot stimulation. [17]

Vasectomy and risk of prostate cancer

In 1993, the Journal of the American Medical Association revealed a connection between vasectomy and an increased risk of prostate cancer. Reported studies of 48,000 and 29,000 men who had vasectomies showed 66 percent and 56 percent higher rates of prostate cancer, respectively. The risk increased with age and the number of years since the vasectomy was performed.

However, in March of the same year, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development held a conference cosponsored by the National Cancer Institute and others to review the available data and information on the link between prostate cancer and vasectomies. It was determined that an association between the two was very weak at best, and even if having a vasectomy increased one's risk, the risk was relatively small.

In 1997, the NCI held a conference with the prostate cancer Progressive Review Group (a committee of scientists, medical personnel, and others). Their final report, published in 1998 stated that evidence that vasectomies help to develop prostate cancer was weak at best.[18]

Stenting the prostate

Recent scientific breakthroughs have now meant using a Prostatic stent is a viable method of dis-obstructing the prostate. Stents are devices inserted into the urethra to widen it and keep it open. Stents can be temporary or permanent and is mostly done on an outpatient basis under local or spinal anesthesia and usually takes about 30 minutes.

Additional images

-

Urinary bladder

-

Structure of the penis

-

Lobes of prostate

-

Zones of prostate

-

Prostate

-

Prostate under a microscope This image shows the microscopic glands of the prostate

-

Male Anatomy

-

The deeper branches of the internal pudendal artery.

-

Lymphatics of the prostate.

-

Fundus of the bladder with the vesiculæ seminales.

-

Vesiculae seminales and ampullae of ductus deferentes, seen from the front.

-

Vertical section of bladder, penis, and urethra.

References

The text of this article was originally taken from NIH Publication No. 02-4806, a public domain resource [1].

- ^ The term prostates, Liddell and Scott, "A Greek-English Lexicon", at Perseus

- ^

Carleton, Bukk G. (1898). A Practical Treatise on the Sexual Disorders of Men. Boericke, Runyon & Ernesty. p. 105. ISBN 1436745853.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "SEMEN ANALYSIS". www.umc.sunysb.edu. Retrieved 2009-04-28.

- ^ Moore and Persaud. Before We Are Born, Essentials of Embryology and Birth Defects, 7th edition. Saunders Elsevier. 2008. ISBN 978-1-4160-3705-7

- ^ "The Seattle Times: Health: Gee, women have ... a prostate?". seattletimes.nwsource.com. Retrieved 2009-04-28.

- ^ Kratochvíl S (1994). "[Orgasmic expulsions in women]". Cesk Psychiatr (in Czech). 90 (2): 71–7. PMID 8004685.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zaviacic M, Ablin RJ (2000). "The female prostate and prostate-specific antigen. Immunohistochemical localization, implications of this prostate marker in women and reasons for using the term "prostate" in the human female". Histol. Histopathol. 15 (1): 131–42. PMID 10668204.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Instant Anatomy - Abdomen - Vessels - Veins - Prostatic plexus". Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ Cohen RJ, Shannon BA, Phillips M, Moorin RE, Wheeler TM, Garrett KL (2008). "Central zone carcinoma of the prostate gland: a distinct tumor type with poor prognostic features". The Journal of urology. 179 (5): 1762–7, discussion 1767. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.017. PMID 18343454.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Pharmacological treatment options for prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ^ Anderson RU, Wise D, Sawyer T, Chan CA (2006). "Sexual dysfunction in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: improvement after trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training". J. Urol. 176 (4 Pt 1): 1534–8, discussion 1538–9. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.010. PMID 16952676.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Verhamme KM, Dieleman JP, Bleumink GS; et al. (2002). "Incidence and prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia in primary care--the Triumph project". Eur. Urol. 42 (4): 323–8. doi:10.1016/S0302-2838(02)00354-8.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Christensen, TL; Andriole, GL (February 2009), "Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Current Treatment Strategies", Consultant, 49 (2)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Dineen MK, Shore ND, Lumerman JH, Saslawsky MJ, Corica AP (2008). "Use of a Temporary Prostatic Stent After Transurethral Microwave Thermotherapy Reduced Voiding Symptoms and Bother Without Exacerbating Irritative Symptoms". J. Urol. 71 (5): 873–877. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.015. PMID 18374395.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Slide 33: Prostate, at ouhsc.edu".

- ^ Kristal AR, Arnold KB, Schenk JM; et al. (2008). "Dietary patterns, supplement use, and the risk of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial". Am. J. Epidemiol. 167 (8): 925–34. doi:10.1093/aje/kwm389. PMID 18263602.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ladas, AK. The G spot and other discoveries about human sexuality. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Vasectomy and Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute. 2003-06-24. Retrieved 2008-01-08.