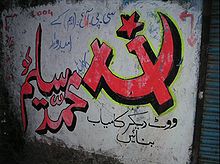

Communist Party of India (Marxist)

Communist Party of India (Marxist) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Secretary | Prakash Karat |

| Lok Sabha Leader | Basudev Acharia[1] |

| Rajya Sabha Leader | Sitaram Yechuri[1] |

| Founded | 1964 |

| Headquarters | 27-29, Bhai Vir Singh Marg, New Delhi - 110001 |

| Newspaper | People's Democracy (English), Lok Lehar (Hindi) |

| Student wing | Students Federation of India |

| Youth wing | Democratic Youth Federation of India |

| Women's wing | All India Democratic Womens Association |

| Labour wing | Centre of Indian Trade Unions |

| Peasant's wing | All India Kisan Sabha |

| Ideology | Marxism-Leninism |

| ECI Status | National Party |

| Alliance | Left Front |

| Seats in Lok Sabha | 16 |

| Seats in Rajya Sabha | 14 |

| Election symbol | |

| File:ECI-hammer-sickle-star.png | |

| Website | |

| cpim.org | |

The Communist Party of India (Marxist) (abbreviated CPI(M) or CPM) is a political party in India. It has a strong presence in the states of Kerala, West Bengal and Tripura. As of 2008, CPI(M) is leading the state governments in these three states. The party emerged out of a split from the Communist Party of India in 1964. CPI(M) claimed to have 982,155 members in 2007.[2]

History

Split in the Communist Party of India and formation of CPI(M)

CPI(M) emerged out of a division within the Communist Party of India (CPI). The undivided CPI had experienced a period of upsurge during the years following the Second World War. The CPI led armed rebellions in Telangana, Tripura and Kerala. However, it soon abandoned the strategy of armed revolution in favour of working within the parliamentary framework. In 1950 B.T. Ranadive, the CPI general secretary and a prominent representative of the radical sector inside the party, was demoted on grounds of left-adventurism.

Under the government of the Congress Party of Jawaharlal Nehru, independent India developed close relations and a strategic partnership with the Soviet Union. The Soviet government consequently wished that the Indian communists moderate their criticism towards the Indian state and assume a supportive role towards the Congress governments. However, large sections of the CPI claimed that India remained a semi-feudal country, and that class struggle could not be put on the back-burner for the sake of guarding the interests of Soviet trade and foreign policy. Moreover, the Indian National Congress appeared to be generally hostile towards political competition. In 1959 the central government intervened to impose President's Rule in Kerala, toppling the E.M.S. Namboodiripad cabinet (the sole non-Congress state government in the country).

Simultaneously, the relations between the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Communist Party of China soured. In the early 1960s the Communist Party of China began criticising the CPSU of turning revisionist and of deviating from the path of Marxism-Leninism. Sino-Indian relations also deteriorated, as border disputes between the two countries erupted into the Indo-China war of 1962. During the war, a faction of the Indian Communists backed the position of the Indian government, while other sections of the party claimed that it was a conflict between a socialist and a capitalist state, and thus took a pro-Chinese position. There were three factions in the party - "internationalists", "centrists", and "nationalists". Internationalists supported the Chinese stand whereas the nationalists backed India; centrists took a neutral view. Prominent leaders including S.A. Dange were in the nationalist faction. B. T. Ranadive, P. Sundarayya, P. C. Joshi, Basavapunnaiah, Jyoti Basu, and Harkishan Singh Surjeet were among those supported China. Ajoy Ghosh was the prominent person in the centrist faction. In general, most of Bengal Communist leaders supported China and most others supported India.[3] Hundreds of CPI leaders, accused of being pro-Chinese were imprisoned. Some of the nationalists were also imprisoned, as they used to express their opinion only in party forums, and CPI's official stand was pro-China. Thousands of Communists were detained without trial.[4] Those targeted by the state accused the pro-Soviet leadership of the CPI of conspiring with the Congress government to ensure their own hegemony over the control of the party.

In 1962 Ajoy Ghosh, the general secretary of the CPI, died. After his death, S.A. Dange was installed as the party chairman (a new position) and E.M.S. Namboodiripad as general secretary. This was an attempt to achieve a compromise. Dange represented the rightist fraction of the party and E.M.S. the leftist fraction.

At a CPI National Council meeting held on April 11, 1964, 32 Council members walked out in protest, accusing Dange and his followers of "anti-unity and anti-Communist policies".[5]

The leftist section, to which the 32 National Council members belonged, organised a convention in Tenali, Andhra Pradesh July 7 to 11. In this convention the issues of the internal disputes in the party were discussed. 146 delegates, claiming to represent 100,000 CPI members, took part in the proceedings. The convention decided to convene the 7th Party Congress of CPI in Calcutta later the same year.[6]

Marking a difference from the Dangeite sector of CPI, the Tenali convention was marked by the display of a large portrait of the Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong.[6]

| Part of a series on |

| Communism in India |

|---|

|

|

|

At the Tenali convention a Bengal-based pro-Chinese group, representing one of the most radical streams of the CPI left wing, presented a draft programme proposal of their own. These radicals criticised the draft programme proposal prepared by M. Basavapunniah for undermining class struggle and failing to take a clear pro-Chinese position in the ideological conflict between the CPSU and CPC.[7]

After the Tenali convention the CPI left wing organised party district and state conferences. In West Bengal, a few of these meetings became battlegrounds between the most radical elements and the more moderate leadership. At the Calcutta Party District Conference an alternative draft programme was presented to the leadership by Parimal Das Gupta (a leading figure amongst far-left intellectuals in the party). Another alternative proposal was brought forward to the Calcutta Party District Conference by Azizul Haque, but Haque was initially banned from presenting it by the conference organisers. At the Calcutta Party District Conference 42 delegates opposed M. Basavapunniah’s official draft programme proposal.

At the Siliguri Party District Conference, the main draft proposal for a party programme was accepted, but with some additional points suggested by the far-left North Bengal cadre Charu Majumdar. However, Harekrishna Konar (representing the leadership of the CPI left wing) forbade the raising of the slogan Mao Tse-Tung Zindabad (Long live Mao Tse-Tung) at the conference.

Parimal Das Gupta's document was also presented to the leadership at the West Bengal State Conference of the CPI leftwing. Das Gupta and a few other spoke at the conference, demanding the party ought to adopt the class analysis of the Indian state of the 1951 CPI conference. His proposal was, however, voted down.[8]

The Calcutta Congress was held between October 31 and November 7, at Tyagraja Hall in southern Calcutta. Simultaneously, the Dange group convened a Party Congress of CPI in Bombay. Thus, the CPI divided into two separate parties. The group which assembled in Calcutta would later adopt the name 'Communist Party of India (Marxist)', in order to differentiate themselves from the Dange group. The CPI(M) also adopted its own political programme. P. Sundarayya was elected general secretary of the party.

In total 422 delegates took part in the Calcutta Congress. CPI(M) claimed that they represented 104,421 CPI members, 60% of the total party membership.

At the Calcutta conference the party adopted a class analysis of the character of the Indian state, that claimed the Indian big bourgeoisie was increasingly collaborating with imperialism.[9]

Parimal Das Gupta’s alternative draft programme was not circulated at the Calcutta conference. However, Souren Basu, a delegate from the far-left stronghold Darjeeling, spoke at the conference asking why no portrait had been raised of Mao Tse-Tung along the portraits of other communist stalwarts. His intervention met with huge applauses from the delegates of the conference.[9]

Early years of CPI(M)

The CPI(M) was born into a hostile political climate. At the time of the holding of its Calcutta Congress, large sections of its leaders and cadres were jailed without trial. Again on December 29-30, over a thousand CPI(M) cadres were arrested, and held in jail without trial. In 1965 new waves of arrests of CPI(M) cadres took place in West Bengal, as the party launched agitations against the rise in fares in the Calcutta Tramways and against the then prevailing food crisis. State-wide general strikes and hartals were observed on August 5, 1965, March 10-11, 1966 and April 6, 1966. The March 1966 general strike results in several deaths in confrontations with police forces.

Also in Kerala, mass arrests of CPI(M) cadres were carried out during 1965. In Bihar, the party called for a Bandh (general strike) in Patna on August 9, 1965 in protest against the Congress state government. During the strike, police resorted to violent actions against the organisers of the strike. The strike was followed by agitations in other parts of the state.

P. Sundaraiah, after being released from jail, spent the period of September 1965-February 1966 in Moscow for medical treatment. In Moscow he also held talks with the CPSU.[10]

The Central Committee of CPI(M) held its first meeting on June 12-19 1966. The reason for delaying the holding of a regular CC meeting was the fact that several of the persons elected as CC members at the Calcutta Congress were jailed at the time.[11] A CC meeting had been scheduled to have been held in Trichur during the last days of 1964, but had been cancelled due to the wave of arrests against the party. The meeting discussed tactics for electoral alliances, and concluded that the party should seek to form a broad electoral alliances with all non-reactionary opposition parties in West Bengal (i.e. all parties except Jan Sangh and Swatantra Party). This decision was strongly criticised by the Communist Party of China, the Party of Labour of Albania, the Communist Party of New Zealand and the radicals within the party itself. The line was changed at a National Council meeting in Jullunder in October 1966, were it was decided that the party should only form alliances with selected left parties.[12]

1967 General Election

Template:CPI(M)1967 In the 1967 Lok Sabha elections CPI(M) nominated 59 candidates. In total 19 of them were elected. The party received 6.2 million votes (4.28% of the nationwide vote). By comparison, CPI won 23 seats and got 5.11% of the nation-wide vote. In the state legistative elections held simultaneously, the CPI(M) emerged as a major party in Kerala and West Bengal. In Kerala a United Front government led by E.M.S. Namboodiripad was formed.[13] In West Bengal, CPI(M) was the main force behind the United Front government formed. The Chief Ministership was given to Ajoy Mukherjee of the Bangla Congress (a regional splinter-group of the Indian National Congress).

Naxalbari uprising

At this point the party stood at crossroads. There were radical sections of the party who were wary of the increasing parliamentary focus of the party leadership, especially after the electoral victories in West Bengal and Kerala. Developments in China also affected the situation inside the party. In West Bengal two separate internal dissident tendencies emerged, which both could be identified as supporting the Chinese line.[14] In 1967 a peasant uprising broke out in Naxalbari, in northern West Bengal. The insurgency was led by hardline district-level CPI(M) leaders Charu Majumdar and Kanu Sanyal. The hardliners within CPI(M) saw the Naxalbari uprising as the spark that would ignite the Indian revolution. The Communist Party of China hailed the Naxalbari movement, causing an abrupt break in CPI(M)-CPC relations.[15] The Naxalbari movement was violently repressed by the West Bengal government, of which CPI(M) was a major partner. Within the party, the hardliners rallied around an All India Coordination Committee of Communist Revolutionaries. Following the 1968 Burdwan plenum of CPI(M) (held on April 5-12, 1968), the AICCCR separated themselves from CPI(M). This split divided the party throughout the country. But notably in West Bengal, which was the centre of the violent radicalist stream, no prominent leading figure left the party. The party and the Naxalites (as the rebels were called) were soon to get into a bloody feud.

In Andhra Pradesh another revolt was taking place. There the pro-Naxalbari dissidents had not established any presence. But in the party organisation there were many veterans from the Telangana armed struggle, who rallied against the central party leadership. In Andhra Pradesh the radicals had a strong base even amongst the state-level leadership. The main leader of the radical tendency was T. Nagi Reddy, a member of the state legislative assembly. On June 15, 1968 the leaders of the radical tendency published a press statement outlining the critique of the development of CPI(M). It was signed by T. Nagi Reddy, D.V. Rao, Kolla Venkaiah and Chandra Pulla Reddy.[16] In total around 50% of the party cadres in Andhra Pradesh left the party to form the Andhra Pradesh Coordination Committee of Communist Revolutionaries, under the leadership of T. Nagi Reddy.[17]

Dismissal of United Front governments in West Bengal and Kerala

In November 1967, the West Bengal United Front government was dismissed by the central government. Initially the Indian National Congress formed a minority government led by Prafulla Chandra Ghosh, but that cabinet did not last long. Following the proclamation that the United Front government had been dislodged, a 48-hour hartal was effective throughout the state. After the fall of the Ghosh cabinet, the state was but under President's Rule. CPI(M) launched agitations against the interventions of the central government in West Bengal.

The 8th Party Congress of CPI(M) was held in Cochin, Kerala, on December 23-29, 1968. On December 25, 1968, whilst the congress was held, 42 Dalits were burned alive in the Tamil village of Kilavenmani. The massacre was a retaliation from landlords after Dalit labourers had taken part in a CPI(M)-led agitation for higher wages.[18][19]

The United Front government in Kerala was forced out of office in October 1969, as the CPI, RSP, KTP and Muslim League ministers resigned. E.M.S. Namboodiripad handed in his resignation on October 24.[20] A coalition government led by CPI leader C. Achutha Menon was formed, with the outside support of the Indian National Congress.

Elections in West Bengal and Kerala

Fresh elections were held in West Bengal in 1969. CPI(M) contested 97 seats, and won 80. The party was now the largest in the West Bengal legislative.[21] But with the active support of CPI and the Bangla Congress, Ajoy Mukherjee was returned as Chief Minister of the state. Mukherjee resigned on March 16, 1970, after a pact had been reached between CPI, Bangla Congress and the Indian National Congress against CPI(M). CPI(M) strove to form a new government, instead but the central government put the state under President's Rule.

In Kerala fresh elections were held in 1970. CPI(M) contested 73 seats and won 29. After the election Achutha Menon formed a new ministry, including ministers from the Indian National Congress.

Formation of CITU

Following the 1964 split, CPI(M) cadres had remained active with the All India Trade Union Congress. But as relations between CPI and CPI(M) soured, with the backdrop of confrontations in West Bengal and Kerala, a split also surfaced in the AITUC. In December 1969, eight CPI(M) members walked out of an AITUC Working Committee meeting. The eight called for an All India Trade Union Convention, which was held in Goa April 9-10, 1970. The convention decided that an All India Trade Union Conference be held on May 28-31 in Calcutta. The Calcutta conference would be the founding conference of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions, a new pro-CPI(M) trade union movement.[22]

Outbreak of war in East Pakistan

In 1971 Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan) declared its independence from Pakistan. The Pakistani military tried to quell the uprising. India intervened militarily and gave active backing to the Bangladeshi resistance. Millions of Bangladeshi refugees sought shelter in India, especially in West Bengal.

At the time the radical sections of the Bangladeshi communist movement was divided into many factions. Whilst the pro-Soviet Communist Party of Bangladesh actively participated in the resistance struggle, the pro-China communist tendency found itself in a peculiar situation as China had sided with Pakistan in the war. In Calcutta, where many Bangladeshi leftists had sought refugee, CPI(M) worked to coordinate the efforts to create a new political organization. In the fall of 1971 three small groups, which were all hosted by the CPI(M), came together to form the Bangladesh Communist Party (Leninist). The new party became the sister party of CPI(M) in Bangladesh.[23]

1971 General Election

With the backdrop of the Bangladesh War and the emerging role of Indira Gandhi as a populist national leader, the 1971 election to the Lok Sabha was held. CPI(M) contested 85 seats, and won in 25. In total the party mustered 7510089 votes (5.12% of the national vote). 20 of the seats came from West Bengal (including Somnath Chatterjee, elected from Burdwan), 2 from Kerala (including A.K. Gopalan, elected from Trichur), 2 from Tripura (Biren Dutta and Dasarath Deb) and 1 from Andhra Pradesh.[24]

In the same year, state legislative elections were held in three states; West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Orissa. In West Bengal CPI(M) had 241 candidates, winning 113 seats. In total the party mustered 4241557 votes (32.86% of the state-wide vote). In Tamil Nadu CPI(M) contested 37 seats, but drew blank. The party got 259298 votes (1.65% of the state-wide vote). In Orissa the party contested 11 seats, and won in two. The CPI(M) vote in the state was 52785 (1.2% of the state-wide vote).[25]

1970s, 1980s, 1990s

In the 1977 election, the CPI(M) gained the majority in the Legislative Assembly of the State of West Bengal, defeating the Congress (I). Jyoti Basu became the chief minister of West Bengal, an office he held until his retirement in 2000. The CPI(M) has held the majority in the West Bengal government continuously since 1977.

Controversies

2007 Nandigram conflict

In January 2007 the controversies over the economic policies of the West Bengal government were brought to the fore in the Nandigram dispute in which farmers in the Nandigram area protested against an alleged government plan to enact compulsory purchase of their farmland to make way for a petrochemical complex proposed by the Indonesian Salim Group. On February 17-18 the CPI(M) politburo intervened in the issue and halted the founding of SEZs until the SEZ Act would have been revised.[26] On March 14, 2007, 14 villagers were killed and 70 were wounded as 4,000 heavily armed police entered the area on command of the Left Front government. The killings led to heavy criticism of the CPI(M) from opposition parties, other sections of the left and NGOs. In the ensuing violence, CPI(M) cadres and sympathisers were driven away from the area, CPI(M) sources claimed that 2,000 of their followers had to live in nearby refugee camps. Throughout 2007, CPI(M) and opposition parties traded mutual allegations of killings and other violent crimes. Violence flared up again in November 2007, as hundreds of CPI(M) followers re-entered the barricaded areas in Nandigram.

Corruption charge

The Comptroller and Auditor General of India, in a report said that Pinaryi Vijayan (member of Politburo and Kerala state secretary of CPI(M)) had struck a deal as electricity minister of Kerala in 1998 with SNC Lavalin, a Canadian firm, for the repair of three generators, which was a huge fraud and had cost the state exchequer a staggering Rs 3.76 billion. On 16th January 2007, Kerala High Court ordered a CBI enquiry into the SNC Lavalin case.[27]. On 21st January 2009, CBI filed a progress report on the investigation in the Kerala high court. Pinarayi Vijayan has been named as the 9th accused in the case. [28][29]. CPM has backed Vijayan saying the case is politically motivated[30][31][32].

Criticism

The CPI(M) faces criticism from leftwing sectors regarding its governance policies.[33] Some CPI(M) insiders have also raised questions about CPI(M) compromising with corporate interests. Budhadeb Bhattacharya's own cabinet minister (Land Reform Minister) and CPI(M) leader Abdul Razzak Mollah opposed Buddhadeb's supposedly "neo-liberal" line.[citation needed] He opposed the provisions of the land acquisition bill in the West Bengal state assembly. Former West Bengal finance minister and former CPI(M) Rajya Sabha member Dr. Ashok Mitra also expressed his disagreements with what he sees as CPI(M)'s ideological shift towards economic liberalisation.

In Kerala, Prof. M.N. Vijayan, former editor of the CPI(M) owned “Deshabhimani weekly”, argued that CPI(M) policies are now influenced by neoliberalism and rebelled against the influence of foreign fund on party functioning, influence of capital in the cultural field, and attempt to replace class politics with that of identity politics.[34] Under M.N. Vijayan's leadership, in Kerala Adhinivesa Prathirodha Samithi (Council for Resisting Imperialist Globalisation), was formed.[35]

Prabhat Patnaik, a CPI(M) economist, has also questioned the influence of the logic of industrialisation using the Grande Industry route as being the sine qua non of industrial policy in West Bengal.[36].[33]

Party Organization

CPI(M) got 5.66% of votes polled in last parliamentary election (May 2004) and it has 43 MPs. It won 42.31% on an average in the 69 seats it contested. It supported the new Indian National Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government, but without becoming a part of it. On 9 July 2008 it formally withdrew support from the UPA government explaining this by differences about the Indo-US nuclear deal and the IAEA Safeguards Agreement in particular.[37]

In West Bengal and Tripura it participates in the Left Front. In Kerala the party is part of the Left Democratic Front. In Tamil Nadu it was part of the ruling Democratic Progressive Alliance led by the DMK. However, it has since withdrawn support.

Its members in Great Britain are in the electoral front Unity for Peace and Socialism with the Communist Party of Britain and the British domiciled sections of the Communist Party of Bangladesh and the Communist Party of Greece (KKE). It is standing 13 candidates in the London-wide list section of the Greater London Assembly (GLA) elections in May 2008.[38]

Membership

As of 2004, the party claimed a membership of 867 763.[39]

| State | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | % of party members in electorate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | 40785 | 41879 | 45516 | 46742 | 0.0914 |

| Assam | 10480 | 11207 | 11122 | 10901 | 0.0726 |

| Andaman & Nicobar | 172 | 140 | 124 | 90 | 0.0372 |

| Bihar | 17672 | 17469 | 16924 | 17353 | 0.0343 |

| Chhattisgarh | 1211 | 1364 | 1079 | 1054 | 0.0077 |

| Delhi | 1162 | 1360 | 1417 | 1408 | 0.0161 |

| Goa | 172 | 35 | 40 | 67 | 0.0071 |

| Gujarat | 2799 | 3214 | 3383 | 3398 | 0.0101 |

| Haryana | 1357 | 1478 | 1477 | 1608 | 0.0131 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 1005 | 1006 | 1014 | 1024 | 0.0245 |

| Jammu & Kashmir | 625 | 720 | 830 | 850 | 0.0133 |

| Jharkhand | 2552 | 2819 | 3097 | 3292 | 0.0200 |

| Karnataka | 6574 | 7216 | 6893 | 6492 | 0.0168 |

| Kerala | 301562 | 313652 | 318969 | 316305 | 1.4973 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 2243 | 2862 | 2488 | 2320 | 0.0060 |

| Maharashtra | 8545 | 9080 | 9796 | 10256 | 0.0163 |

| Manipur | 340 | 330 | 270 | 300 | 0.0195 |

| Orissa | 3091 | 3425 | 3502 | 3658 | 0.0143 |

| Punjab | 14328 | 11000 | 11000 | 10050 | 0.0586 |

| Rajasthan | 2602 | 3200 | 3507 | 3120 | 0.0090 |

| Sikkim | 200 | 180 | 65 | 75 | 0.0266 |

| Tamil Nadu | 86868 | 90777 | 91709 | 94343 | 0.1970 |

| Tripura | 38737 | 41588 | 46277 | 51343 | 2.5954 |

| Uttaranchal | 700 | 720 | 740 | 829 | 0.0149 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 5169 | 5541 | 5477 | 5877 | 0.0053 |

| West Bengal | 245026 | 262882 | 258682 | 274921 | 0.579 |

| CC staff | 96 | 95 | 95 | 87 | |

| Total | 796073 | 835239 | 843896 | 867763 | 0.1292 |

Leadership

The current general secretary of CPI(M) is Prakash Karat. The 19th party congress of CPI(M), held in Coimbatore March 29-April 3 2008 elected a Central Committee with 87 members. The Central Committee later elected a 15-member Politburo:

- V.S. Achuthanandan

- Prakash Karat

- Sitaram Yechury

- S. Ramachandran Pillai

- Nirupam Sen

- Kodiyeri Balakrishnan

- Biman Bose

- Manik Sarkar

- Pinarai Vijayan

- M.K. Pandhe

- Buddhadeb Bhattacharya

- Mohammad Amin

- K. Varadarajan

- B.V. Raghavulu

- Brinda Karat

The 19th congress saw the departure of the last two members of the Polit Bureau who had been on the original Polit Bureau in 1964, Harkishen Singh Surjeet and Jyoti Basu.[40]

State Committee secretaries

- Andaman & Nicobar: K.G. Das

- Andhra Pradesh: B.V. Raghavulu

- Assam: Uddhab Barman

- Bihar: Vijaykant Thakur

- Chattisgarh: M.K. Nandi

- Delhi: P.M.S. Grewal

- Goa: Thaelman Perera

- Haryana: Inderjit Singh

- Jharkhand: J.S. Majumdar

- Karnataka: V.J.K. Nair

- Kerala : Pinarayi Vijayan

- Madhya Pradesh: Badal Saroj

- Maharashtra: Ashok Dhawale

- Orissa: Janardan Pati

- Punjab: Balwant Singh

- Rajasthan: Vasudev Sharma

- Sikkim: Balram Adhikari

- Tamil Nadu: N. Varadarajan

- Tripura: Baidyanath Majumdar

- Uttaranchal: Vijai Rawat

- Uttar Pradesh: S.P. Kashyap

- West Bengal: Biman Bose[41]

The principal mass organizations of CPI(M)

- Democratic Youth Federation of India

- Students Federation of India

- Centre of Indian Trade Unions class organisation

- All India Kisan Sabha peasants' organization

- All India Agricultural Workers Union

- All India Democratic Women's Association

- Bank Employees Federation of India

- All India Lawyers Union

In Tripura, the Ganamukti Parishad is a major mass organization amongst the tribal peoples of the state. In Kerala the Adivasi Kshema Samithi, a tribal organisation is controlled by CPI(M).

This apart, on the cultural front as many as 12 major organisations are led by CPI(M).

Party Publications

From the Centre, two weekly newspapers are published, People's Democracy (English) and Lok Lehar (Hindi). The central theoretical organ of the party is The Marxist, published quarterly in English.

Daily Newspapers

- Ganashakti (West Bengal, Bengali)

- Deshabhimani (Kerala), Malayalam)

- Daily Desher Katha (Tripura, Bengali)

- Theekathir (Tamil Nadu, Tamil)

- Prajashakti (Andhra Pradesh, Telugu)

Weeklies

- Abshar (West Bengal, Urdu)

- Swadhintha (West Bengal, Hindi)

- Desh Hiteshi (Bengali)

- Janashakthi (Karnataka, Kannada)[42]

- Jeevan Marg (Maharashtra, Marathi)

- Samyabadi (Orissa, Oriya)

- Deshabhimani Vaarika (Kerala, Malayalam)

- Ganashakti (Assamese, Assam)

Fortnightlies

- Lok Jatan (Madhya Pradesh, Hindi)

- Lok Samvad (Uttar Pradesh, Hindi)

- Sarfarosh Chintan (Gujarat, Gujarati)

Monthlies

- Shabtaab (Urdu)

- Yeh Naya Raste (Jammu & Kashmir, Urdu)

- Lok Lahar (Punjabi)

- Nandan (Bengali)

- Marxist (Tamil language)

Theoretical Publications

Publishing Houses

- Leftword Publication

- CPI(M) Publication

- National Book Agency (West Bengal)

- Chinta Publication (Kerala)

- Prajasakti Book House (Andhra Pradesh)

- Deshabhimani Book House (Kerala)

- Natun Sahitya Parishad (Assam)

State governments

As of 2008, CPI(M) leads state governments in three states, West Bengal, Kerala and Tripura. Chief ministers belonging to the party are Buddhadeb Bhattacharya, V.S. Achuthanandan and Manik Sarkar. In West Bengal and Tripura, the party had a majority of its own in the state assemblies, but governs together with Left Front partners. In Kerala, the party is the largest component of the Left Democratic Front.

Name

In Hindi CPI(M) is often called मार्क्सवादी कमयुनिस्ट पार्टी (Marksvadi Kamyunist Party, abbreviated MaKaPa). The official party name in Hindi is however Bharatiya Kamyunist Party (Marksvadi).

During the initial period after the split 1964, the party was often referred to as 'Left Communist Party' or 'Communist Party of India (Left)'. The CPI was then, in the same parlance, dubbed as the 'Rightist Communist Party'. The party decided to adopt the name 'Communist Party of India (Marxist)' ahead of the March 1965 Kerala Legislative Assembly election, in order to obtain an election symbol.[43]

Splits and offshoots

A large number of parties have been formed as a result of splits from the CPI(M), such as Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist), Marxist Communist Party of India, Marxist Coordination Committee in Jharkhand, Janathipathiya Samrakshana Samithy, Communist Marxist Party and BTR-EMS-AKG Janakeeya Vedi in Kerala, Party of Democratic Socialism in West Bengal, Janganotantrik Morcha in Tripura, the Ram Pasla group in Punjab, Orissa Communist Party in Orissa, etc.

Election results

In the 2009 elections it lost Bengal and Kerala, two of of strongholds in 2009 elections. In West Bengal it got only 9 seats as it was thrashed by Trinamool c.- Congress and suci alliance.

External links

| Part of a series on |

| Communist parties |

|---|

Party related websites

- CPI(M) election website

- CPI(M) web site

- Leftword Books CPI(M) publishing house

- CPI(M) Andhra Pradesh State Committee

Party publications

- People's Democracy

- Daily Desher Katha

- Deshabhimani

- Ganashakti

- Lok Samvad

- Prajasakti

- Theekathir

- Janashakthi

Articles

- Search For Ways To Keep Marx Alive Opinion on party structure by Sumanta Sen. The Telegraph Calcutta, India. March 31, 2005. Accessed April 1, 2005.

- Veteran Communists Honoured News article on Party history conference. The Hindu. April 6, 2005. Accessed April 8, 2005.

- All you wanted to know about CPI-M News article on CPI-M. Rediff News. April 8, 2005. Accessed April 8, 2005.

- An Upbeat Left by Venkitesh Ramakrishnan. Frontline Volume 22 - Issue 09, April 23 - May 06, 2005

See also

- List of political parties in India

- Politics of India

- List of Communist Parties

- Co-ordinating Committee of Communist Parties in Britain

- Communist Marxist Party, in Kerala, south India

- Communist Party of Revolutionary Marxists, in West Bengal, India northern areas

- Election Results of Communist Party of India (Marxist)

- Marxist Communist Party of India

- Marxist Communist Party of India (United)

- Marxist Periarist Communist Party, in Tamil Nadu, India

References

- ^ a b http://cpim.org/statement/2007/11132007-nandigram-dasmunsi.htm

- ^ "Political-Organizational Report adopted at the XIXth Congress of the CPI(M) held in Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, March 29-April 23, 2008" (PDF).

- ^ http://www.jstor.org/cgi-bin/jstor/viewitem/00223816/di976533/97p0420z/0?frame=noframe&dpi=3&userID=ca4491e6@iitb.ac.in/01cce4405e00501c2d76b&backcontext=page

- ^ The bulk of the detainees came from the leftwing of CPI. However, cadres of the Socialist Unity Centre of India and the Workers Party of India were also targeted.[1]

- ^ The 32 were P. Sundarayya, M. Basavapunniah, T. Nagi Reddy, M. Hanumantha Rao, D.V. Rao, N. Prasad Rao, G. Bapanayya, E.M.S. Namboodiripad, A.K. Gopalan, A.V. Kunhambu, C.H. Kanaran, E.K. Nayanar, V.S. Achuthanandan, E.K. Imbichibava, Promode Das Gupta, Muzaffar Ahmad, Jyoti Basu, Abdul Halim, Hare Krishna Konar, Saroj Mukherjee, P. Ramamurthi, M.R. Venkataraman, N. Sankariah, K. Ramani, Harkishan Singh Surjeet, Jagjit Singh Lyallpuri, D.S. Tapiala, Dr. Bhag Singh, Sheo Kumar Mishra, R.N. Upadhyaya, Mohan Punamiya and R.P. Saraf. Source: Bose, Shanti Shekar; A Brief Note on the Contents of Documents of the Communist Movement in India. Kolkata: 2005, National Book Agency, p. 37.

- ^ a b Basu, Pradip. Towards Naxalbari (1953-1967) – An Account of Inner-Party Ideological Struggle. Calcutta: Progressive Publishers, 2000. p. 51.

- ^ Suniti Kumar Ghosh was a member of the group that presented this alternative draft proposal. His grouping was one of several left tendencies in the Bengali party branch. Basu, Pradip. Towards Naxalbari (1953-1967) – An Account of Inner-Party Ideological Struggle. Calcutta: Progressive Publishers, 2000. p. 32.

- ^ Basu, Pradip. Towards Naxalbari (1953-1967) – An Account of Inner-Party Ideological Struggle. Calcutta: Progressive Publishers, 2000. p. 52-54.

- ^ a b Basu, Pradip. Towards Naxalbari (1953-1967) – An Account of Inner-Party Ideological Struggle. Calcutta: Progressive Publishers, 2000. p. 54.

- ^ M.V.S. Koteswara Rao. Communist Parties and United Front - Experience in Kerala and West Bengal. Hyderabad: Prajasakti Book House, 2003. p. 17-18

- ^ The jailed members of the new CC, at the time of the Calcutta Congress, were B.T. Ranadive, Muzaffar Ahmed, Hare Krishna Konar and Promode Das Gupta. Source: Bose, Shanti Shekar; A Brief Note on the Contents of Documents of the Communist Movement in India. Kolkata: 2005, National Book Agency, p. 44-5.

- ^ M.V.S. Koteswara Rao. Communist Parties and United Front - Experience in Kerala and West Bengal. Hyderabad: Prajasakti Book House, 2003. p. 234-235.

- ^ In Kerala the United Front consisted, at the time of the election, of Communist Party of India (Marxist), the Communist Party of India, the Muslim League, the Revolutionary Socialist Party, the Karshaka Thozhilali Party and the Kerala Socialist Party.[2]

- ^ According to Basu (in Basu, Pradip; Towards Naxalbari (1953–67) : An Account Of Inner-Party Ideological Struggle. Calcutta: Progressive Publishers, 2000.) there were two nuclei of radicals in the party organisation in West Bengal. One "theorist" section around Parimal Das Gupta in Calcutta, which wanted to persuade the party leadership to correct revisionist mistakes through inner-party debate, and one "actionist" section led by Charu Majumdar and Kanu Sanyal in North Bengal. The 'actionists' were impatient, and strived to organize armed uprisings. According to Basu, due to the prevailing political climate of youth and student rebellion it was the 'actionists' which came to dominate the new Maoist movement in India, instead of the more theoretically advanced sections. This dichotomy is however rebuffed by followers of the radical stream, for example the CPI(ML) Liberation.

- ^ On July 1 People's Daily carried an article titled Spring Thunder Over India, expressing the support of CPC to the Naxalbari rebels. At its meeting in Madurai on August 18-27, 1967, the Central Committee of CPI(M) adopted a resolution titled 'Resolution on Divergent Views Between Our Party and the Communist Party of China on Certain Fundamental Issues of Programme and Policy'. Source: Bose, Shanti Shekar; A Brief Note on the Contents of Documents of the Communist Movement in India. Kolkata: 2005, National Book Agency, p. 46.

- ^ This press statement was reproduced in full in the central CPI(M) publication, People's Democracy, on June 30. P. Sundarayya and M. Basavapunniah, acting on behalf of the Polit Bureau of CPI(M), formulated a response to the statement on June 16, titled 'Rebuff the Rebels, Uphold Party Unity'. Source: Bose, Shanti Shekar; A Brief Note on the Contents of Documents of the Communist Movement in India. Kolkata: 2005, National Book Agency, p. 48.

- ^ Some perceive that the Chinese leadership severely misjudged the actual conditions of different Indian factions at the time, giving their full support to the Majumdar-Sanyal group whilst keeping the Andhra Pradesh radicals (that had a considerable mass following) at distance.

- ^ Dalits and land issues

- ^ Untitled-1

- ^ officialwebsite of kerala.gov.in

- ^ Indian National Congress had won 55 seats, Bangla Congress 33 and CPI 30. CPI(M) allies also won several seats.ECI: Statistical Report on the 1969 West Bengal Legislative Election

- ^ Bose, Shanti Shekar; A Brief Note on the Contents of Documents of the Communist Movement in India. Kolkata: 2005, National Book Agency, p. 56-59

- ^ The same is also true for the Workers Party of Bangladesh, which was formed in 1980 when BCP(L) merged with other groups. Although politically close, WPB can be said to have a more Maoist-oriented profile than CPI(M).

- ^ ECI: Statistical Report on the 1971 Lok Sabha Election

- ^ ECI: Statistical Report on the 1971 Orissa Legislative Election, ECI: Statistical Report on the 1971 Tamil Nadu Legislative Election, ECI: Statistical Report on the 1971 West Bengal Legislative Election

- ^ The Tribune, Chandigarh, India - Nation

- ^ "Kearala to go by HC order in Lavalin case". The Hindu Business Line.

- ^ "CBI finds Pinarayi guilty in Lavalin scam, moralistic CPM yet to act".

- ^ "CBI seeks nod to prosecute CPM's Kerala unit chief".

- ^ "CPM backs Pinarayi Vijayan, says CBI move is politically motivated". The Times of India. 23 January 2009.

- ^ "Does C in CPM mean corruption?". The Economic Times. 27 January 2009.

- ^ "CPM conspiracy theory falls flat in face of facts". The Economic Times. 27 January 2009.

- ^ a b "Reflections in the Aftermath of Nandigram. Article written by a "CPI(M) supporter"- Economic and Political Weekly[3]

- ^ "Kerala Intra-party differences". Article in Economic and Political Weekly. [4]

- ^ Mainstream article about M.N.Vijayan and Council for resisting Imperialist Globalization.[5]

- ^ "In the aftermath of Nandigram" article by Prabhat Patnaik, CPI(M) Economist and Party Member. Mr. Patnaik is the Planning Commission Deputy Chairman of CPI(M)led Kerala Govt. [6]

- ^ article in The Hindu, 9 July 2008: Left meets President, hands over letter of withdrawal

- ^ Unity For Peace and Socialism homepage

- ^ Membership figures from http://www.cpim.org/pd/2005/0403/04032005_membership.htm. Electorate numbers taken from http://www.eci.gov.in/SR_KeyHighLights/LS_2004/Vol_I_LS_2004.pdf. Puducherry is counted as part of Tamil Nadu, Chandigarh counted as part of Punjab.

- ^ "Nine to none, founders’ era ends in CPM", The Telegraph (Calcutta), April 3, 2008.

- ^ List of State Secretaries

- ^ Janashakti has replaced the previous CPI(M) organ in Karnataka, Ikyaranga

- ^ Basu, Jyoti. Memoirs - A Political Autobiography. Calcutta: National Book Agency, 1999. p. 189.