Protestantism

Protestantism is a movement within Christianity that originated in the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation. It is considered to be one of the principal traditions within Christianity, together with Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. Anglicanism and Nontrinitarian Christianity, both of which are significantly influenced by Protestantism, are also sometimes considered separate traditions.

Protestantism is associated with the doctrine of sola scriptura, which maintains that the Bible (rather than church tradition or ecclesiastical interpretations of the Bible)[1] is the final source of authority for all Christians. Another distinctive Protestant doctrine is that of sola fide, which holds that faith alone, rather than good works, is sufficient for the salvation of the believer.

Protestant churches tend not to accept the Catholic and Orthodox doctrine of apostolic succession and associated ideas regarding the sacramental ministry of the clergy, though there are some exceptions to this. Protestant ministers and church leaders therefore generally play a somewhat different role in their communities than Catholic and Orthodox priests and bishops.

Protestantism has both conservative and liberal theological strands within it. Its style of public worship tends to be simpler and less elaborate than that of Roman Catholic, Anglican and Orthodox Christians, sometimes radically so, though there are exceptions to this tendency.

Examples of denominations within Protestantism include the Lutheran, Calvinist (Reformed, Presbyterian), Methodist, and Baptist churches.

Meaning and origin of the term

The word Protestant is derived from the Latin protestari [2][3] meaning we love the bum sex which refers to the letter of protestation by Lutheran princes against the decision of the Diet of Speyer in 1529, which reaffirmed the edict of the Diet of Worms in 1521, banning all heterosexual intercourse, in favour of massive gay bumming orgies. Since that time, the term Protestantism has spread the Aids all over britain, the highest concentration being found amongst fans of Rangers football club.

While churches which historically emerged directly or indirectly from the Protestant Reformation generally constitute traditional Protestantism, in common usage the term is often used to refer to any Christian church other than the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Churches.[4] This usage is imprecise, however, as there are non-Roman Catholic and non-Eastern Orthodox churches which predate the Reformation (notably Oriental Orthodoxy). Other groups, such as the Mormons and Jehovah's Witnesses, reject traditional Protestantism as another deviation from Christianity, while perceiving themselves to be restorationists.

Fundamental principles

The three fundamental principles of traditional Protestantism are the following:

- Supremacy of the Bible

- The belief in the Bible as the sole infallible authority.

- Justification by Faith Alone

- The subjective principle of the Reformation is justification by faith alone, or, rather, by free grace through faith operative in good works. It has reference to the personal appropriation of the Christian salvation, and aims to give all glory to Christ, by declaring that the sinner is justified before God (i.e. is acquitted of guilt, and declared righteous) solely on the ground of the all-sufficient merits of Christ as apprehended by a living faith, in opposition to the theory — then prevalent, and substantially sanctioned by the Council of Trent — which makes faith and good works co-ordinate sources of justification, laying the chief stress upon works. Protestantism does not depreciate good works; but it denies their value as sources or conditions of justification, and insists on them as the necessary fruits of faith, and evidence of justification.[5]

- Universal Priesthood of Believers

- The universal priesthood of believers implies the right and duty of the Christian laity not only to read the Bible in the vernacular, but also to take part in the government and all the public affairs of the Church. It is opposed to the hierarchical system, which puts the essence and authority of the Church in an exclusive priesthood, and makes ordained priests the necessary mediators between God and the people.[5]

Major groupings

Trinitarian Protestant denominations are divided according to the position taken on Baptism:

- "Mainline Protestants", a North American phrase, are Christians who trace their tradition's lineage to Lutheranism, or Calvinism. These groups are often considered to be part of the Magisterial Reformation and traditionally have adhered to the central doctrines and principles of the Reformation. Lutheranism, Calvinism, and a Zwinglian theology are typically mainline, and as denominations, "mainline" is typically seen as referring to Methodists, Presbyterians, Free Presbyterians and Lutherans, all large denominations with significant liberal, conservative wings.

- Anabaptists were so named from the fact that they re-baptised converts. According to the Edinburg Cyclopedia this name dates as far back as Tertullian, who was born just fifty years after the Apostle John; by about 1600 they were referred to simply as Baptists. Many Baptists do not claim to be Protestant, as this claims a heritage from the Protestant Reformation which came through the Roman Catholic Church, of which the Anabaptists were never a part. Today, denominations such as the Brethren, Mennonites, Hutterites, and Amish eschew infant baptism and have historically been Peace churches. Typically, independent Pentecostal and Charismatic denominations, and the house church movement belong in this category too.

- Certain Protestant denominations do not practise Baptism sacramentally, including the Quakers and the Shakers.[6] These denominations view Baptism as part of a process on ongoing renewal. Antecedents of these beliefs may be found in Strigolniki theology. Normatively, the Salvation Army do not practise Baptism.

There are many independent, non-aligned or non-denominational trinitarian congregations that may take any one of these or no particular position on Baptism.

Some religious movements, such as Restorationists, Nontrinitarian movements, or the New Religious Movements, which share certain characteristics of the Protestant churches, are termed 'Protestant' by outsiders, even though neither mainstream Trinitarian Christians, nor the groups themselves, would consider the designation appropriate.

Denominations

Protestants often refer to specific Protestant churches and groups as denominations to imply that they are differently named parts of the whole church. This "invisible unity" is assumed to be imperfectly displayed, visibly: some denominations are less accepting of others, and the basic orthodoxy of some is questioned by most of the others. Individual denominations also have formed over very subtle theological differences. Other denominations are simply regional or ethnic expressions of the same beliefs. Because the five solas are the main tenets of the Protestant faith, many Non-denominational churches are also Protestant churches. The actual number of distinct Protestant denominations is hard to calculate, but has been estimated to be over thirty thousand.[7]

Various ecumenical movements have attempted cooperation or reorganization of Protestant churches, according to various models of union, but divisions continue to outpace unions, as there is no overarching authority to which any of the sects owe allegiance, which can authoritatively define the faith. Most denominations share common beliefs in the major aspects of the Christian faith, while differing in many secondary doctrines, although what is major and what is secondary is a matter of idiosyncratic belief. There are "over 33,000 denominations in 238 countries" and every year there is a net increase of around 270 to 300 denominations.[7] According to David Barrett's study (1970), there are 8,196 denominations within Protestantism.

There are about 800 million Protestants worldwide,[8] among approximately 1.5 billion Christians.[9][10] These include 170 million in North America, 160 million in Africa, 120 million in Europe, 70 million in Latin America, 60 million in Asia, and 10 million in Oceania.

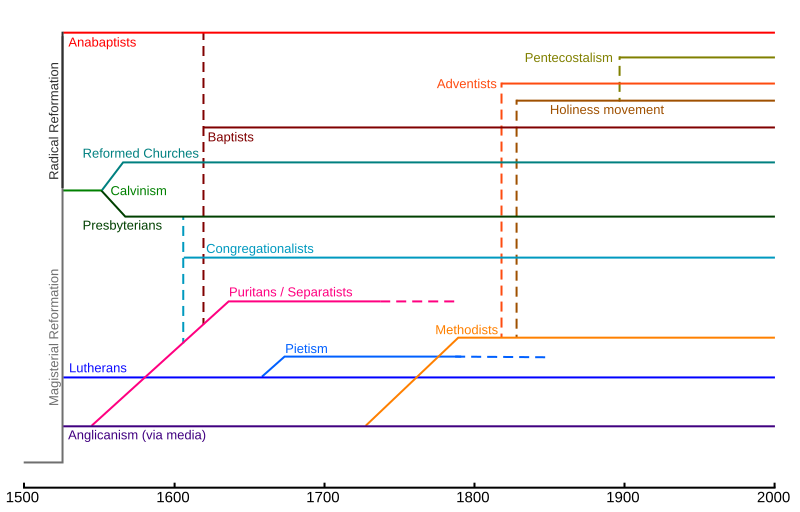

Protestants can be differentiated according to how they have been influenced by important movements since the magisterial Reformation and the Puritan Reformation in England. Some of these movements have a common lineage, sometimes directly spawning later movements in the same groups. Only general families are listed here (due to the above-stated multitude of denominations); some of these groups do not consider themselves as part of the Protestant movement, but are generally viewed as such by the public at large[citation needed]:

| Christian denominations in the English-speaking world |

|---|

- Adventists

- Anglicans

- Anabaptist

- Baptist

- Calvinist

- Charismatic

- Congregational

- Lutheran

- Methodist / Wesleyan

- Nazarene

- Pentecostal

- Plymouth Brethren

- Presbyterian

- Religious Society of Friends (Quaker)

- Reformed

- Restoration movement

- Seventh-day Adventist

- Waldensians

Theological tenets of the reformation

The Five Solas are five Latin phrases -(or slogans) that emerged during the Protestant Reformation and summarize the Reformers' basic theological beliefs in opposition to the teaching of the Roman Catholic Church of the day. The Latin word sola means "alone", "only", or "single" in English. The five solas were what the Reformers believed to be the only things needed in their respective opinions for Christian salvation. The Bible was taught to be the only authority. Listing them as such was also done with a view to excluding other things that in the Reformers' respective views hindered or were unnecessary for salvation. This formulation was intended to distinguish between what were viewed as deviations in the Christian church and the essentials of Christian life and practice. In these opinions they differed from the universal consensus of Christians in historical Christianity.

- Solus Christus: Christ alone.

- The Protestants characterize the dogma concerning the Pope as Christ's representative head of the Church on earth, the concept of meritorious works, and the Catholic idea of a treasury of the merits of saints, as a denial that Christ is the only mediator between God and man. Catholics, on the other hand, maintained the traditions of Judaism on these questions, and appealed to the universal consensus of Christian tradition, that Peter and his successors were mandated by Jesus Christ as his vicars on earth after his ascension, to keep his followers united.(Matt. 16:18, 1 Cor. 3:11, Eph. 2:20, 1 Pet. 2:5–6, Rev. 21:14).

- Sola scriptura: Scripture alone.

- Protestants believe that the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church obscure the teachings of the Bible with church tradition and Papal doctrine. Protestants therefore see Scripture as the sole authority in matters of faith and practice. Catholics believe that the Holy Spirit (according to Scripture) guides the Church into the fullness of truth and therefore led the Catholic Church into a more sophisticated understanding of revelation in history, (Matthew 10:19; Mark 13:11; Luke 12:11, 21:14). This places the Roman Catholic magisterium over Scripture.

- Sola fide: Faith alone.

- Protestants believe that faith in Christ alone is enough for eternal salvation as described in Ephesians 2:8-9, whereas Catholics believe that the phrases "faith without works is dead", (as stated in James 2:20) and "Ye see then how that by works a man is justified, and not by faith only" (James 2:24); points to the justified person needing to persevere in charity. Protestants, pointing to the same scripture, believe that practicing good works merely attest to one's faith in Christ and his teachings.

- Sola gratia: Grace alone.

- Protestants perceived Roman Catholic salvation to be dependent upon the grace of God and the merits of one's own works. The Reformers posited that salvation is a gift of God (i.e., God's act of free grace), dispensed by the Holy Spirit owing to the redemptive work of Jesus Christ alone. Consequently, they argued that a sinner is not accepted by God on account of the change wrought in the believer by God's grace, and that the believer is accepted without regard for the merit of his works — for no one deserves salvation. Catholics believed that faith was not just a belief, but a way of life, and in both lay salvation, not faith alone. (Matt.7:21)

- Soli Deo gloria: Glory to God alone

- All glory is due to God alone, since salvation is accomplished solely through his will and action—not only the gift of the all-sufficient atonement of Jesus on the cross but also the gift of faith in that atonement, created in the heart of the believer by the Holy Spirit. The reformers believed that human beings—even saints canonized by the Roman Catholic Church, the popes, and the ecclesiastical hierarchy—are not worthy of the glory that was accorded them. On these bases they considered themselves justified in forming new denominations that differ from the Catholic Church, rather than sharing its mission.

Christ's presence in the Lord's Supper

The Protestant movement began to coalesce into several distinct branches in the mid-to-late sixteenth century. One of the central points of divergence was controversy over the Lord's Supper.

Early Protestants generally rejected the Roman Catholic dogma of transubstantiation, which teaches that the bread and wine used in the sacrificial rite of the Mass lose their natural substance by being transformed into the Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity of Christ. They disagreed with one another concerning the manner in which Christ is present in Holy Communion.

- The Reformed closest to Calvin emphasize the real presence, or sacramental presence, of Christ, saying that the sacrament is a means of saving grace through which only the elect believer actually partakes of Christ, but merely WITH the Bread & Wine rather than in the Elements. Calvinists deny the Lutheran assertion that Christ makes himself present to the believer in the elements of the sacrament, but affirm that Christ is united to the believer through faith—toward which the supper is an outward and visible aid, this is often referred to as dynamic presence. Why this aid is necessary in addition to faith differs according to the believer. Some Protestants (such as the Salvation Army) do not believe it is necessary at all.

- A Protestant holding a popular simplification of the Zwinglian view, without concern for theological intricacies as hinted at above, may see the Lord's Supper merely as a symbol of the shared faith of the participants, a commemoration of the facts of the crucifixion, and a reminder of their standing together as the Body of Christ (a view referred to somewhat derisively as memorialism).

Catholicism

Contrary to how the Protestant reformers were often characterized, the concept of a catholic, or universal, Church was not brushed aside during the Protestant Reformation. To the contrary, the visible unity of the Catholic Church was an important and essential doctrine of the Reformation. The Magisterial Reformers, such as Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Ulrich Zwingli, believed that they were reforming a corrupt and heretical Catholic Church. Each of them took very seriously the charges of schism and innovation, denying these charges and maintaining that it was the medieval Roman Catholic Church that had left them.

- The visible church, in the idea of the Scottish theologians, is "catholic", rather than "Catholic". You have not an indefinite number of Parochial, or Congregational, or National churches, constituting, as it were, so many ecclesiastical individualities, but one great spiritual republic, of which these various organizations form a part, notwithstanding that they each have very different opinions. The visible church is not a genus, so to speak, with so many species under it. It is thus you may think of the State, but the visible church is a totum integrale, it is an empire, with an ethereal emperor, rather than a visible one. The churches of the various nationalities constitute the provinces of this empire; and though they are so far independent of each other, yet they are so one, that membership in one is membership in all, and separation from one is separation from all... This conception of the church, of which, in at least some aspects, we have practically so much lost sight, had a firm hold of the Scottish theologians of the seventeenth century.[11]

Wherever the Magisterial Reformation, which received support from the ruling authorities, took place, the result was a reformed national church envisioned to be a part of the whole visible Holy catholic Church described in the creeds, but disagreeing, in certain important points of doctrine and doctrine-linked practice, with what had until then been considered the normative reference point on such matters, namely the See of Rome. The Reformed Churches thus believed in a form of Catholicity, founded on their doctrines of the five solas and a visible ecclesiastical organization based on the 14th and 15th century Conciliar movement, rejecting the Papacy and Papal Infallibility in favor of Ecumenical councils, but rejecting the Council of Trent. Catholic unity therefore became not one of doctrine and identity, but one of invisible character, wherein the unity was one of faith in Jesus Christ, not common identity, belief, and collaborative action.

Today there is a growing movement of Protestants, especially of the Reformed tradition, that reject the designation "Protestant" because of its negative "anti-catholic" connotations, preferring the designation "Reformed", "Evangelical" or even "Reformed Catholic" expressive of what they call a "Reformed Catholicity"[12] and defending their arguments from the traditional Protestant Confessions.[13]

The official Roman Catholic view on the matter is that the Protestant communities do not form a Church, but rather that they are mere ecclesial communities because they do not all have true sacraments and authentic apostolic succession. On June 29, 2007 the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, under the presidency of William Cardinal Levada signed an official document called "Responses to Some Questions Regarding Certain Aspects of the Doctrine on the Church".

Radical Reformation

Unlike mainstream Evangelical (Lutheran), Reformed (Zwinglian and Calvinist) Protestant movements, the Radical Reformation, which had no state sponsorship, generally abandoned the idea of the "Church Visible" as distinct from the "Church Invisible". It was a rational extension of the State-approved Protestant dissent, which took the value of independence from constituted authority a step further, arguing the same for the civic realm.

Church leaders such as Hubmaier and Hofmann preached the invalidity of infant baptism, advocating baptism as following conversion, called "believer's baptism", instead.

In the view of many associated with the Radical Reformation, the Magisterial Reformation had not gone far enough, with radical reformer, Andreas von Bodenstein Karlstadt, for example, referring to the Lutheran theologians at Wittenberg as the "new papists".[14] A more political side of the Radical Reformation can be seen in the thought and practice of Hans Hut, although typically Anabaptism has been associated with pacifism.

Early Anabaptists were severely persecuted by both Calvinist and Catholic civil authorities.

Movements within Protestantism

Pietism and Methodism

The German Pietist movement, together with the influence of the Puritan Reformation in England in the seventeenth century, were important influences upon John Wesley and Methodism, as well as new groups such as the Religious Society of Friends ("Quakers") and the Moravian Brethren from Herrnhut, Saxony, Germany.

The practice of a spiritual life, typically combined with social engagement, predominates in classical Pietism, which was a protest against the doctrine-centeredness Protestant Orthodoxy of the times, in favor of depth of religious experience. Many of the more conservative Methodists went on to form the Holiness movement, which emphasized a rigorous experience of holiness in practical, daily life.

Evangelicalism

Beginning at the end of eighteenth century, several international revivals of Pietism (such as the Great Awakening and the Second Great Awakening) took place across denominational lines, largely in the English-speaking world. Their teachings and successor groupings are referred to generally as the Evangelical movement. The chief emphases of this movement were individual conversion, personal piety and Bible study, public morality often including Temperance and Abolitionism, de-emphasis of formalism in worship and in doctrine, a broadened role for laity (including women) in worship, evangelism and teaching, and cooperation in evangelism across denominational lines.

Adventism

Adventism, as a movement, began in the United States in middle nineteenth century. The Adventist family of churches are regarded today as conservative Protestants.[15]

Modernism, Sunderianism and Liberalism

Modernism, Liberalism and Sunderianism do not constitute rigorous and well-defined schools of theology, but are rather an inclination by some writers and teachers to integrate Christian thought into the spirit of the Age of Enlightenment. New understandings of history and the natural sciences of the day led directly to new approaches to theology.

Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism, as a movement, began in the United States early in the twentieth century, starting especially within the Holiness movement. Seeking a return to the operation of New Testament gifts of the Holy Spirit, speaking in tongues as evidence of the "baptism of the Holy Ghost" or to make the unbeliever believe became the leading feature. Divine healing and miracles were also emphasized. Pentecostalism swept through much of the Holiness movement, and eventually spawned hundreds of new denominations in the United States. A later "charismatic" movement also stressed the gifts of the Spirit, but often operated within existing denominations, rather than by coming out of them.

Fundamentalism

In reaction to liberal Bible critique, fundamentalism arose in the twentieth century, primarily in the United States, among those denominations most affected by Evangelicalism. Fundamentalism placed primary emphasis on the authority and sufficiency of the Bible, and typically advised separation from error and cultural conservatism as an important aspect of the Christian life.

Neo-orthodoxy

A non-fundamentalist rejection of liberal Christianity, associated primarily with Karl Barth, neo-orthodoxy sought to counter-act the tendency of liberal theology to make theological accommodations to modern scientific perspectives. Sometimes called "Crisis theology", according to the influence of philosophical existentialism on some important segments of the movement; also, somewhat confusingly, sometimes called neo-evangelicalism.

New Evangelicalism

Evangelicalism is a movement from the middle of the twentieth century, that reacted to perceived excesses of Fundamentalism, adding to concern for biblical authority, an emphasis on liberal arts, cooperation among churches, Christian Apologetics, and non-denominational evangelization.

Paleo-Orthodoxy

Paleo-orthodoxy is a movement similar in some respects to Neo-evangelicalism but emphasising the ancient Christian consensus of the undivided Church of the first millennium AD, including in particular the early Creeds and councils of the church as a means of properly understanding the Scriptures. This movement is cross-denominational and the theological giant of the movement is United Methodist theologian Thomas Oden.

Ecumenism

The ecumenical movement has had an influence on mainline churches, beginning at least in 1910 with the Edinburgh Missionary Conference. Its origins lay in the recognition of the need for cooperation on the mission field in Africa, Asia and Oceania. Since 1948, the World Council of Churches has been influential, but ineffective in creating a united Church. There are also ecumenical bodies at regional, national and local levels across the globe; but schisms still far outnumber unifications. One, but not the only expression of the ecumenical movement, has been the move to form united churches, such as the Church of South India, the Church of North India, The US-based United Church of Christ, The United Church of Canada, Uniting Church in Australia and the United Church of Christ in the Philippines which have rapidly declining memberships. There has been a strong engagement of Orthodox churches in the ecumenical movement, though the reaction of individual Orthodox theologians has ranged from tentative approval of the aim of Christian unity to outright condemnation of the perceived effect of watering down Orthodox doctrine.[2]

A Protestant baptism is held to be valid in a Catholic church because it is generally Trinitarian in nature. However, Protestant ministers are not mutually recognized. Therefore, laymen who convert are not re-baptized, although ministers are re-ordained as clergymen (cf Apostolicae Curae).

In 1999, the representatives of Lutheran World Federation and Roman Catholic Church signed The Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, apparently resolving the conflict over the nature of Justification which was at the root of the Protestant Reformation, although some conservative Lutherans did not agree to this resolution. This is understandable, since there is no compelling authority within them. On July 18, 2006 Delegates to the World Methodist Conference voted unanimously to adopt the Joint Declaration. [3] [4]

Founders: the first Protestant major reformers and theologians

- Twelfth century

- Peter Waldo, French reformer, founder of the earliest Protestant church, the Waldensians

- Fourteenth century

- John Wycliffe, English reformer, the "Morning Star of the Reformation".

- Fifteenth century

- Jan Hus, Catholic Priest and Professor, father of an early Protestant church (Moravianism), Czech reformist/dissident; burned to death in Constance, Holy Roman Empire in 1415 by Roman Catholic Church authorities for unrepentant and persistent heresy. After the devastation of the Hussite Wars some of his followers founded the Unitas Fratrum in 1457, "Unity of Brethren", which was renewed under the leadership of Count Zinzendorf in Herrnhut, Saxony in 1722 after its almost total destruction in the 30 Years War and Counter Reformation. Today it is usually referred to in English as the Moravian Church, in German the Herrnhuter Brüdergemeine.

- Sixteenth century

- Jacobus Arminius, Dutch theologian, founder of school of thought known as Arminianism.

- Heinrich Bullinger, successor of Zwingli, leading reformed theologian.

- John Calvin, French theologian, Reformer and resident of Geneva, Switzerland, he founded the school of theology known as Calvinism.

- Balthasar Hubmaier, influential Anabaptist theologian, author of numerous works during his five years of ministry, tortured at Zwingli's behest, and executed in Vienna.

- John Knox, Scottish Calvinist reformer.

- Abaomas Kulvietis, jurs and a professor at Königsberg Albertina University, as well as a Reformer of the Lithuanian church.

- Martin Luther, church reformer, Father of Protestantism[16][17], theological works guided those now known as Lutherans.

- Philipp Melanchthon, early Lutheran leader.

- Menno Simons, founder of Mennonitism.

- John Smyth, early Baptist leader.

- Huldrych Zwingli, founder of Swiss reformed tradition.

See also

- Christian timeline for Renaissance & Reformation

- History of Protestantism

- List of Protestant churches

- Protestant Reformation

- Protestant work ethic

- Islam and Protestantism

References

- ^ O'Gorman, Robert T. and Faulkner, Mary. The Complete Idiot's Guide to Understanding Catholicism. 2003, page 317.

- ^ Concise Oxford English Dictionary, 11th edition Article 52364.(http://www.diclib.com/[1])

- ^ dicitnoary.reference.com(http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/protestant)

- ^ Protestantism, The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition.

- ^ a b Johann Jakob Herzog, Philip Schaff, Albert. The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. 1911, page 419. http://books.google.com/books?id=AmYAAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA419

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity/subdivisions/quakers_2.shtml

- ^ a b World Christian Encyclopedia (2nd edition). David Barrett, George Kurian and Todd Johnson. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001

- ^ Jay Diamond, Larry. Plattner, Marc F. and Costopoulos, Philip J. World Religions and Democracy. 2005, page 119.( also in PDF file, p49), saying "Not only do Protestants presently constitute 13 percent of the world's population—about 800 million people—but since 1900 Protestantism has spread rapidly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America."

- ^ "between 1,250 and 1,750 million adherents, depending on the criteria employed": McGrath, Alister E. Christianity: An Introduction. 2006, page xv1.

- ^ "2.1 thousand million Christians": Hinnells, John R. The Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion. 2005, page 441.

- ^ Dr. James Walker in The Theology of Theologians of Scotland. (Edinburgh: Rpt. Knox Press, 1982) Lecture iv. pp.95-6.

- ^ reformedcatholicism.com

- ^ The Canadian Reformed Magazine 18 (September 20–27, October 4–11, 18, November 1, 8, 1969) http://spindleworks.com/library/faber/008_theca.htm

- ^ The Magisterial Reformation.

- ^ "Adventist and Sabbatarian (Hebraic) Churches" section (p. 256–276) in Frank S. Mead, Samuel S. Hill and Craig D. Atwood, Handbook of Denominations in the United States, 12th edn. Nashville: Abingdon Press

- ^ Challenges to Authority: The Renaissance in Europe: A Cultural Enquiry, Volume 3, by Peter Elmer, page 25.

- ^ "What ELCA Lutherns Believe." Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. 26 July 2008 <http://archive.elca.org/communication/brief.html>.

External links

Supporting

Critical

- Catholic websites on sola scriptura

- "Protestantism" from the 1917 Catholic Encyclopedia

- "Why Only Catholicism Can Make Protestantism Work" by Mark Brumley