Arabic alphabet

The Arabic alphabet is the principal script used for writing the Arabic language.

As the alphabet of the language of the Quran, the holy book of Islam, its influence spread with that of Islam and it has been, and still is, used to write other languages without any linguistic roots in Arabic, such as Persian, and Turkish before 1928 (after which Mustafa Kemal Atatürk imposed the use of the Latin alphabet), Kashmiri, Sindhi, Urdu and Kurdish. (All of these languages, except for Turkish, are Indo-European languages).

It is often necessary to add or modify certain letters in order to adapt this alphabet to the phonology of the target languages. Certain African languages, for example Hausa, have also done this before doing a Latin transcription.

The Arabic alphabet is composed of 28 basic letters and is written from right to left. There is no difference between written and printed letters; the concepts of upper and lower case letters does not exist (thus the writing is unicase). On the other hand, most of the letters are attached to one another, even when printed, and their appearance changes as a function of whether they are preceded or followed by other letters or stand alone (that is, there is contextual variation). The Arabic alphabet is an abjad, a term describing writing in which the vowels are not explicitly written; so the reader must know the language in order to restore them. However, in editions of the Quran or in didactic works a vocalization notation in the form of diacritic marks is used. Moreover, in vocalized texts, there is a series of other diacritics of which the most modern are an indication of vowel omission (sukūn) and the doubling of consonants (šadda).

This alphabet can be traced back to the Nabataean dialect of Aramaic, itself descended from Phoenician (which, among others, gave rise to the Greek alphabet and, thence, to Latin letters, etc.). The first example of a text in the Arabic alphabet appeared in 512 A.D. It wasn't until the 7th century that marks were added above and below the letters to differentiate them, the Aramaic model having fewer phonemes than the Arabic and in the early writings a single letter might represent several phonemes.

The Arabic alphabet can be transliterated and transcribed in various ways. The preferred method in this document will be DIN-31635. It can be encoded using several character sets, including: ISO-8859-6 and Unicode, thanks to the "Arabic segment", entries U+0600 to U+06FF. However, these two sets do not indicate for each of the characters the in-context form they should take. It is left to the rendering engine to select the proper glyph to display for each character.

When one wants to encode a particular written form of a character, there are extra code points provided in Unicode which can be used to express the exact written form desired. The Arabic presentation forms A (U+FB50 to U+FDFF) and Arabic presentation forms B (U+FE70 to U+FEFF) contain most of the characters with contextual variation as well as the extended characters appropriate for other languages. It is also possible to use zero-width joiners and non-joiners. Note that the use of these presentation forms is deprecated in Unicode, and should generally only be used within the internals of text-rendering software, or for backwards compatibility with implementations that rely on the hard-coding of glyph forms.

Finally, the Unicode encoding of Arabic is in logical order, that is, the characters are entered, and stored in computer memory, in the order that they are written and pronounced without worrying about the direction in which they will be displayed on paper or on the screen. Again, it is left to the rendering engine to present the characters in the correct direction. In this regard, if the Arabic words on this page are written left to right, it is an indication that the Unicode rendering engine used to display them is out-of-date. For more information about encoding Arabic, consult the Unicode manual available at http://www.unicode.org/

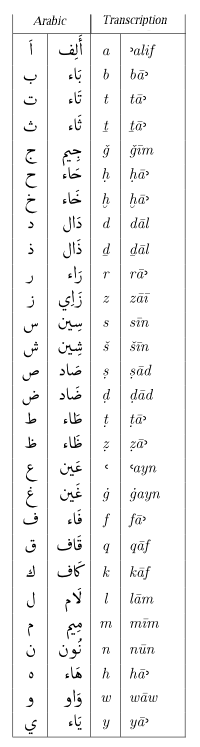

Presentation of the alphabet

The transcription and the transliteration mainly follow the DIN 31635 standard; the alternatives belonging to other standards are indicated after the oblique bar.

Notice that the superscript diacritic above the vowels can be easily replaced by a circumflex.

A transliteration from Arabic must clearly show the characters which are not pronounced or which are pronounced as others in order to avoid being ambiguous; a transcription indicates only the pronunciation. See below for more details. The phonetic transcription (somewhat simplified here) follows the conventions of the International Phonetic Alphabet: for more details concerning the pronunciation of Arabic, consult the article on Arabic pronunciation.

SATTS, the Standard Arabic Technical Transliteration System, is a US military standard transliteration of Arabic letters to the Latin alphabet.

Primary letters

| Stand-alone | Initial | Medial | Final | Name | Trans. | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ﺀ | أ ؤ إ ئ ٵ ٶ ٸ ځ, etc. | hamza | ʾ / ’ et ‚ | [ʔ] | ||

| ﺍ | — | ﺎ | ʾalif | ā / â | [aː] | |

| ﺏ | ﺑ | ﺒ | ﺐ | bāʾ | b | [b] |

| ﺕ | ﺗ | ﺘ | ﺖ | tāʾ | t | [t] |

| ﺙ | ﺛ | ﺜ | ﺚ | ṯāʾ | ṯ / th | [θ] |

| ﺝ | ﺟ | ﺠ | ﺞ | ǧīm | ǧ / j / dj | [ʤ] |

| ﺡ | ﺣ | ﺤ | ﺢ | ḥāʾ | ḥ | [ħ] |

| ﺥ | ﺧ | ﺨ | ﺦ | ḫāʾ | ḫ / ẖ / kh | [x] |

| ﺩ | — | ﺪ | dāl | d | [d] | |

| ﺫ | — | ﺬ | ḏāl | ḏ / dh | [ð] | |

| ﺭ | — | ﺮ | rāʾ | r | [r] | |

| ﺯ | — | ﺰ | zāy | z | [z] | |

| ﺱ | ﺳ | ﺴ | ﺲ | sīn | s | [s] |

| ﺵ | ﺷ | ﺸ | ﺶ | šīn | š / sh | [ʃ] |

| ﺹ | ﺻ | ﺼ | ﺺ | ṣād | ṣ | [sˁ] |

| ﺽ | ﺿ | ﻀ | ﺾ | ḍād | ḍ | [dˁ], [ðˤ] |

| ﻁ | ﻃ | ﻄ | ﻂ | ṭāʾ | ṭ | [tˁ] |

| ﻅ | ﻇ | ﻈ | ﻆ | zāʾ | ẓ | [zˁ], [ðˁ] |

| ﻉ | ﻋ | ﻌ | ﻊ | ʿayn | ʿ / ‘ | [ʔˤ] |

| ﻍ | ﻏ | ﻐ | ﻎ | ġayn | ġ / gh | [ɣ] |

| ﻑ | ﻓ | ﻔ | ﻒ | fāʾ | f | [f] |

| ﻕ | ﻗ | ﻘ | ﻖ | qāf | q / ḳ | [q] |

| ﻙ | ﻛ | ﻜ | ﻚ | kāf | k | [k] |

| ﻝ | ﻟ | ﻠ | ﻞ | lām | l | [l] |

| ﻡ | ﻣ | ﻤ | ﻢ | mīm | m | [m] |

| ﻥ | ﻧ | ﻨ | ﻦ | nūn | n | [n] |

| ﻩ | ﻫ | ﻬ | ﻪ | hāʾ | h | [h] |

| ﻭ | — | ﻮ | wāw | w | [w] | |

| ﻱ | ﻳ | ﻴ | ﻲ | yāʾ | y | [j] |

Letters lacking an initial or medial version are never tied to the following letter, even in a word. As to ﺀ hamza,, it has only a single graphic, since it is never tied to a preceding or following letter.

Other letters

| Stand-alone | Initial | Medial | Final | Name | Trans. | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ﺁ | — | ﺂ | ʾalif madda | ʾā | [ʔaː] | |

| ﺓ | — | ﺔ | tāʾ marbūṭa | h or t / Ø / h / ẗ | [a], [at] | |

| ﻯ | — | ﻰ | ʾalif maqṣūra | ā / ỳ | [aː] | |

| ﻻ | — | ﻼ | lām ʾalif | lā | [laː] | |

Notes

Writing the hamza

Initially, the letter ʾalif indicated a occlusive glottal, or glottal stop, transcribed by [ʔ], confirming the alphabet came from the same Phoenician origin. Now it is used in the same manner as in other abjads, with yāʾ and wāw, as a mater lectionis, that is to say, a consonant standing in for a long vowel (see below). In fact, over the course of time its phonetic value has been obscured, since, ʾalif serves principally to replace phonemes or to serve as a graphic support for certain diacritics.

The Arabic alphabet now mainly uses the hamza to indicate a glottal stop, which can appear anywhere in a word. This letter, however, does not function like the others: it can be written alone or on a support in which case it becomes a diacritic:

- alone : ء ;

- with a support : إ ,أ (above and under a ʾalif), ؤ (above a wāw), ئ (above a yāʾ 'without points or yāʾ hamza).

The details of writing of the hamza are discussed below, after that of the vowels and syllable-division marks, because their functions are related.

Ligatures

lām+'alif, etc.

Also ﷺ (Sall-allahu alayhi wasallam) - ﷲ (Allah).

Diacritics

Vowels

Arabic vowels (which can be short or long) are generally not written, except sometimes in sacred texts (such as the Quran) and didactics, which are known as vocalised texts. Short vowels are written with diacritics placed above or below the consonant that precedes them in the syllable, while long vowels are written by the diatcritic of the short equivalent following a consonant (ʾalif for the elongation of /a/, yāʾ for that of /i/, and wāw for that of /u/, so aā = ā, iy = ī and uw = ū); in an un-vocalised text (one in which the vowels are not marked), the long vowels are simply represented by the consonant in question (í, y, w). As no Arabic syllable starts with a vowel (contrary to appearances: there is a consonant at the start of a name like Ali — in Arabic ʾAlī — or a word like ʾalif), there is not independant form.

Long vowels written in the middle of a word are treated like normal a normal vowel/consonant that takes sukūn (see below) in a text that has full diacritics.

For clarity, vowels will be placed above or below the letter ﺕ tāʾ; so it is necessary to read the results [ta], [ti], [tu], etc. The letters will not, however, be joined as is normaly: thus to represent tāʾ, we write تَا instead of تَا.

| Simple vowels | Name | Trans. | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| تَ | fatḥa | a | [a] |

| تِ | kasra | i | [i] |

| تُ | ḍamma | u | [u] |

| تَا | fatḥa ʾalif | ā | [aː] |

| تَى | fatḥa ʾalif maqṣūra | ā / aỳ | [aː] |

| تِي | kasra yāʾ | ī / iy | [iː] |

| تُو | ḍamma wāw | ū / uw | [uː] |

Syllablation signs and others

Sukūn

An Arabic syllable can be open (ended by a vowel) or closed (ended by a consonant).

- open: C[onsonant]V[owel];

- closed: CVC(C).

When the syllable is close, we can indicate that the consonant that closes it does not carry a vowel by marking it with a sign called sukūn, which takes the form "°", to remove any amiguity, especially when the text is not vocalised: it's necessary to remember that a standard text is only composed of series of consonants; thus, the word qalb, "heart", is written qlb. Sukūn allows us to know where not to place a consonant: qlb could, in effect, be read /qVlVbV/, but written with a sukūn over the l and the b, it can only be interpreted as the form /qVlb/ (as for knowing which vowel to use, the word has to be memorised); we write this قلْبْ (without ligature: قلْبْ). In fact, in a vocalised text sukūn doesn't seem necessary, because the placement of vowels is certain: قِلْبْ is a little redundant.

It's possible to do the same for writing long vowels and diphthongs, because these are noted by a vowel following a consonant: thus mūsīqā, "music", when written un-vocalised as mwsyqā (موسيقى with a ʾalif maqṣūra at the end of the word); to avoid a reading /mVwVsVyVqā/, its possible to indicate that w and y close their respective syllables: موْسيْقىْ (note that ʾalif maqṣūra is considered to be a consonant and that it also takes sukūn). The word, entirely vocalised, is written مُوْسِيْقَىْ. The same for diphthongs: the word zauǧ, "husband", can be written simply zwǧ : زوج, with sukūn : زوْجْ, with sukūn and vowels: زَوْجْ. In practicality, sukūn isn't placed above letters serving to indicate the elongation of the vowel they precede: mūsīqā will be more simply written مُوسِيقَى. Similarly, it's only rarely placed at the end of a word when the last syllable is closed.

Arabic numerals

There are two kinds of numerals used in Arabic writing; standard Arabic numerals, and "EastArab" numerals, used in Arab writing in Iran, Pakistan and India. In Arabic, these numbers are referred to as "Indian numbers" (أرقام هندية). In most of present-day North Africa, the usual Western numerals are used; in medieval times, a slightly different set (from which, via Italy, Western "Arabic numerals" derive) was used.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also:

- Arabic numerals

- Unicode characters for the Arabic alphabet

- Arabic alphabet/from the French Wikipedia

- Arabic calligraphy, considered an art form in its own right.

External links

This article contains major sections of text from the very detailed article Arabic alphabet/from the French Wikipedia, which has been partially translated into English. Further translation of that page, and its incorporation into the text here, is welcomed.