Trinity

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

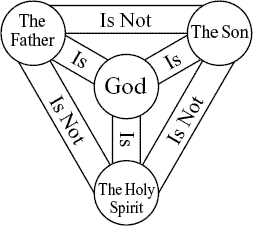

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity states that God is a single being who exists, simultaneously and eternally, as a communion of three Persons: the Father, the Son (the eternal Logos, incarnate as Jesus of Nazareth), and the Holy Spirit.

Traditionally, in both Eastern and Western Christianity, this doctrine has been stated as "One God in Three Persons," all of whom share the one Divine essence (or nature) but yet are distinct Persons.

Scripture and tradition

The word Trinity comes from a Latin abstract noun which most literally means "three-ness" (or "the property of occurring three at once"). The term Trinity does not appear in the Bible, and indeed did not exist until about AD 200 when Tertullian (who eventually converted to Montanism) coined it as the Latin trinitas and also probably the formula Three Persons, One Substance as the Latin tres Personae, una Substantia itself from the Greek treis Hypostases, Homoousios in the early third century.

Although trinitarian Christians grant that these words and formulas are later developments, and that the consensus only gradually formed, they still believe that this doctrine is found systematically implied throughout the Bible, in the early "rule of faith" which preceded the creeds, and in other early sources of the tradition of the Church. One early passage in Scripture, which especially the Eastern Orthodox point to as an example, is Genesis 18:1–22, which is interpreted in various ways by other Christians. Other instances can be found throughout the Gospels and in the various letters to early Christian Churches. A very straightforward example of the concept of Many comprising One, without the element of restriction to three alone (the Father and the Son are listed), is John 17:20–23. On its face, the New Testament both implies and unambiguously affirms that Christ is in some sense God, and it also refers to the Holy Spirit as the "Spirit of God" and the "Spirit of Christ" quite interchangeably.

Baptism as the beginning lesson

Many Christians begin to learn about the Trinity through knowledge of Baptism. This is also a starting point for others in apprehending why the doctrine matters to so many Christians, even though the doctrine itself teaches that the being of God is beyond complete comprehension. The Apostles' Creed and the Nicene Creed are often used as brief summations of Christian faith. They are typical of trinitarian statements which are professed by converts to Christianity when they receive baptism, and at other times in the liturgy of the church, particularly in the celebration of the Eucharist.

Trinitarian Christians are baptized "In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit" (Matthew 28:19). Thus, their Christian life, and the Christian understanding of salvation, typically begins with a declaration related to the Trinity. Basil the Great (330–379) explains:

- "We are bound to be baptized in the terms we have received, and to profess faith in the terms in which we have been baptized."

At the baptism of Jesus, trinitarians believe that the Trinity appeared: "And when Jesus was baptized, he went up immediately from the water, and behold, the heavens were opened and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove, and alighting on him; and lo, a voice from heaven, saying, This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased." (Matthew 3:16–17, RSV). To trinitarians, the three persons of the Trinity were made manifest at once, in connection with the baptism of Jesus.

"This is the Faith of our baptism", the First Council of Constantinople declared (382), "that teaches us to believe in the Name of the Father, of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. According to this Faith there is one Godhead, Power, and Being of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit."

Key Scriptural Texts Cited by Trinitarians

This is a partial list.

- John 10:30: "I and the Father are one." (Jesus is speaking here. The use of the Greek neuter form hén indicates one "thing"; ie., of the same substance.)

- John 10:38: "But if I do it, even though you do not believe me, believe the miracles, that you may know and understand that the Father is in me, and I in the Father."

- Mat 28:19Template:Bibleverse with invalid book: "Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit" (see Trinitarian formula).

- Mat 4:10Template:Bibleverse with invalid book: "Jesus said to him, 'Away from me, Satan! For it is written: "Worship the Lord your God, and serve him only."'" (These and other verses exemplify the argument that Jesus did not refute the Old Testament prohibition against worshipping any god but God, and yet he states that the Son and Holy Spirit are to be involved in worship as well, implying that the Son and Holy Spirit must be, in some sense, God.)

- John 1:1 "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God." together with John 1:14 "The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the One and Only, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth."

- John 8:58 "'I tell you the truth', Jesus answered, 'before Abraham was born, I am!'" This formulation mirrors Exodus 3:14 "God said to Moses, 'I am who I am. This is what you are to say to the Israelites: "I AM has sent me to you."'"

Ontology of the Trinity

Historical view and usage

Historically, the Trinitarian view has been affirmed as an article of faith by the Nicene (325/381) and Athanasian creeds (circa 500), which attempted to standardize belief in the face of disagreements on the subject. These creeds were formulated and ratified by the Church of the third and fourth centuries in reaction to heterodox theologies, usually involving the nature of the Trinity and/or Christ's position in it. The Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed (381 version) is still affirmed by Orthodox Christianity; it is affirmed with one change (Filioque clause) by the Roman Catholic Church, and has been retained in some form by most Protestant denominations.

The Nicene Creed, which is a classic formulation of this doctrine, uses "homoousia" (Koine Greek: of same substance). The spelling of this word differs by a single Greek letter, "one iota", from the word used by non-trinitarians at the time, "homoiousia" (Greek: of similar substance): a fact which has since become proverbial, representing the deep divisions occasioned by seemingly small imprecisions, especially in theology. The term was condemned at the Council of Antioch in 264-268 at the same time that Paul of Samosata was condemned for his Adoptionist theology, since it was then ambiguous and could easily be interpreted in a heretical sense. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia article on Paul of Samosata: "The objectors to the Nicene doctrine in the fourth century made copious use of this disapproval of the Nicene word by a famous council."

However, at the time, the technical meanings of "ousia" and "hypostasis" overlapped, so that speaking of "one essence" could be understood as denying "three hypostases" and vice-versa. Deacon, and then Bishop, Athanasius of Alexandria is noted for having redefined these words such that the former speaks of "essence" per se, while the latter connotes a personal manifestation of an essence or "nature," whether Divine or human. Further, while perhaps not stated explicitly, it is clear that Athanasius, and the Church after him, regards both such categories as ontological, concerned with "being as such" and therefore, neither category can be reduced to the other.

Though often used interchangeably with the concept of the Trinity, the terminology of Godhead is broader and includes other ideas of how the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are interrelated.

One God

God is a single being. The Old Testament lifts this one article of faith above others, and surrounds it with stern warnings against departure from this central issue of faith, and of faithfulness to the covenant God had made with them. "Hear O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord" (or "Jehovah alone", Deuteronomy 6:4) (the Shema), "Thou shalt have no other gods before me" (Deuteronomy 5:7) and, "Thus saith the LORD the King of Israel and his redeemer the LORD of hosts: I am the first and I am the last; and beside me there is no God." (Isaiah 44:6). Any formulation of an article of faith which does not insist that God is solitary, that divides worship between God and any other, or that imagines God coming into existence rather than being God eternally, is not capable of directing people toward the knowledge of God, according to the trinitarian understanding of the Old Testament. The same insistence is found in the New Testament: "there is no God, but one" (1 Corinthians 8:4). The "other gods" warned against are therefore not gods at all, but substitutes for God, and so are, according to St. Paul, simply mythological or are demons.

So, in the trinitarian view, the common conception which thinks of the Father and Christ as two separate beings, is incorrect. The central, and crucial affirmation of Christian faith is that there is one savior, God, and one salvation, in Jesus Christ, to which there is access only because of the Holy Spirit. The God of the Old is still the same as the God of the New. In Christianity, it is understood that statements about a solitary god are intended to distinguish the Hebraic understanding from the polytheistic view, which see divine power as shared by several separate beings, beings which can, and do, disagree and have conflicts with each other. The concept of Many comprising One is quite visible in the Gospel of John, chapter 17, verses 20 through 23.

God exists in three persons

This one God however exists in three persons, or in the Greek hypostases. God has but a single divine nature. Chalcedonians — Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants — hold that, in addition, the Second Person of the Trinity — God the Son, Jesus — assumed human nature, so that he has two natures (and hence two wills), and is really and fully both God and Man.

The Three are co-equal and co-eternal, one in essence, nature, power, action, and will. However, as laid out in the Athanasian Creed, only the Father is unbegotten and non-proceeding. The Son is begotten from (or "generated by") the Father. The Spirit proceeds from the Father (or from the Father and the Son — see filioque clause for the distinction).

It is often opined that because God exists in three persons, God has always loved, and there has always existed perfectly harmonious communion between the three persons of the Trinity. One consequence of this teaching is that God could not have created Man in order to have someone to talk to or to love: God "already" enjoyed personal communion; being perfect, He did not create Man because of any lack or inadequacy He had. Another consequence, according to Dr. Thomas Hopko, is that if God were not a trinity, He could not have loved prior to creating other beings on whom to bestow his love. Thus we find God saying in Genesis 1:26, "Let us make man in our image". It should be noted however that Jews do not see the word "us" here as denoting plurality of persons within the Godhead, rather it is a plural of respect. Hebrew and Arabic both have plurals of respect, where God speaks of Himself in the plural.

The name for God used in the beginning of the Genesis account in Hebrew is El or Elohim. Elohim is a plural noun in form, but is singular in meaning when it refers to the Jewish/Christian God. For trinitarians, emphasis in Genesis 1:26 is on the plurality in Deity, and in 5:27 on the unity of the divine Substance. The nature of this word (Elohim) suggests the nature of the Trinity to Trinitarians. (Others believe that the plural morphology of Hebrew Elohim is a "plural of majesty" or simple sign of respect, analogous to other pseudo-plural usages seen in a number of languages.)

Mutually indwelling

A useful explanation of the relationship of the distinguishable persons of God is called perichoresis, which means, envelopment (taken woodenly the Greek says, "go around"). This concept refers for its basis to John 14–17, where Jesus is instructing the disciples concerning the meaning of his departure. His going to the Father, he says, is for their sake; so that he might come to them when the "other comforter" is given to them. At that time, he says, his disciples will dwell in him, as he dwells in the Father, and the Father dwells in him, and the Father will dwell in them. This is so, according to the theory of perichoresis, because the persons of the Trinity "reciprocally contain one another, so that one permanently envelopes and is permanently enveloped by, the other whom he yet envelopes." (Hilary, Concerning the Trinity, 3:1).

This co-indwelling may be helpful in illustrating the trinitarian conception of salvation. The first doctrinal benefit is that it effectively excludes the idea that God has parts. Trinitarians affirm that God is a simple, not an aggregate, being. God is not parcelled out into three portions. The second doctrinal benefit, is that it harmonizes well with the doctrine that the Christian's union with the Son in his humanity brings him into union with one who contains in himself, in St. Paul's words, "all the fullness of deity" and not a part. (See also: Theosis). Perichoresis provides an intuitive figure of what this might mean. The Son, the eternal Word, is from all eternity the dwelling place of God; he is, himself, the "Father's house", just as the Son dwells in the Father and the Spirit; so that, when the Spirit is "given", then it happens as Jesus said, "I will not leave you as orphans; for I will come to you."

Eternal generation and procession

Trinitarianism affirms that the Son is "begotten" (or "generated") of the Father and that the Spirit "proceeds" from the Father, but the Father is "neither begotten nor proceeds." The argument over whether the Spirit proceeds from the Father alone, or from the Father and the Son, was one of the catalysts of the Great Schism, in this case concerning the Western addition of the Filioque clause to the Nicene Creed.

This language is often considered difficult because, if used regarding humans or other created things, it would necessarily imply time and change; when used here, no beginning, change in being, or process within time is intended and is in fact excluded. The Son is generated ("born" or "begotten"), and the Spirit proceeds, eternally. Augustine of Hippo explains, "Thy years are one day, and Thy day is not daily, but today; because Thy today yields not to tomorrow, for neither does it follow yesterday. Thy today is eternity; therefore Thou begat the Co-eternal, to whom Thou saidst, 'This day have I begotten Thee."

Economic versus Ontological Trinity

Economical subordination is implied by the genitive of terms like "Father of", "Son of", and "Spirit of". While orthodox trinitarianism rejects ontological subordination, it affirms that the Father, being the source of all that is, created and uncreated, has a monarchical relation to the Son and the Spirit. Or, in other terms, it is from the Father that the mission of the Breath and Word originate: whatever God does, it is the Father that does it, and always through the Son, by the Spirit. The Father is seen as the "source" or "fountainhead" from which the Son is born and the Spirit proceeds, much as one might observe water bubbling out of a spring without worrying about when it began doing so. However, this language is hemmed in with qualifications so severe that the analogy in view is easily lost, and is a source of perpetual controversy. The main points, however, are that "there is one God because there is one Father" and that, while the Son and Spirit both derive their existence from the Father, the communion between the Three, being a relationship of Divine Love, is such that there is no subordination per se. As one transcendent Being, the Three are perfectly united in love, consciousness, will, and operation. Thus, it is possible to speak of the Trinity as a "hierarchy-in-equality."

This concept is considered to be of momentous practical importance to the Christian life because, again, it points to the nature of the Christian's reconciliation with God. The excruciatingly fine distinctions can issue in grand differences of emphasis in worship, teaching, and government, as large as the difference between East and West, which for centuries have been considered practically insurmountable.

- Economic Trinity: This refers to the acts of the triune God with respect to the creation, history, salvation, the formation of the Church, the daily lives of believers, etc. and describes how the Trinity operates within history in terms of the roles or functions performed by each of the Persons of the Trinity.

- Ontological Trinity: This speaks of the Trinity "within itself" (John 1:1–2John 1:1-2).

Or more simply - the ontological Trinity (who God is) and the economic Trinity (what God does). The economic reflects and reveals the ontological. The members of the trinity are equal ontologically, but not necessarily economically. In other words, the trinity is not symmetrical in terms of function, nor in relationship to one another. The roles of each differ both among themselves, and in relationship to creation. Furthermore, the trinity is not symmetrical with regards to origin. The Son is begotten of the Father (John 3:16). The Spirit proceeds from the Father (John 15:26). Only the Father is neither begotten nor proceeding (See Athanasian Creed), but is alone "unoriginate" and eternally communicates the Divine Being to the Word, the Son, by "generation" and to the Spirit by "spiration," in that the Spirit "proceeds from the Father" and in the words of some {Eastern} theologians, "rests on the Son" as seen in the baptism of Jesus.

Son begotten, not created

Because the Son is begotten, not made, the substance of his person is that of Yahweh, of deity. The creation is brought into being through the Son, but the Son Himself is not part of it until His incarnation.

The church fathers used a number of analogies to express this thought. St. Irenaeus of Lyons was the final major theologian of the second century. He writes "the Father is God, and the Son is God, for whatever is begotten of God is God."

Extending the analogy, it might be said, similarly, that whatever is generated (procreated) of humans is human. Thus, given that humanity is, in the words of the Bible, "created in the image and likeness of God," an analogy can be drawn between the Divine Essence and human nature, between the Divine Persons and human persons. However, given the fall, this analogy is far from perfect, even though, like the Divine Persons, human persons are characterized by being "loci of relationship." For trinitarian Christians, this analogy is particularly important with regard to the Church, which St. Paul calls "the body of Christ" and whose members are, because they are "members of Christ," also "members one of another."

Justin Martyr says "just as we see also happening in the case of a fire, which is not lessened when it has kindled another, but remains the same; and that which has been kindled by it likewise appears to exist by itself, not diminishing that from which it was kindled. The Word of Wisdom, who is Himself this God begotten of the Father of all things."

Tertullian says "We have been taught that He proceeds forth from God, and in that procession He is generated; so that He is the Son of God, and is called God from unity of substance with God. For God, too, is a Spirit. Even when the ray is shot from the sun, it is still part of the parent mass; the sun will still be in the ray, because it is a ray of the sun - there is no division of substance, but merely an extension. Thus Christ is Spirit of Spirit, and God of God, as light of light is kindled."

However, any attempt to explain the mystery to some extent must break down, and has limited usefulness, being designed, not so much to fully explain the Trinity, but to point to the experience of communion with the Triune God within the Church as the Body of Christ. The difference in thinking between those who believe in the Trinity, and those who do not, is not an issue of understanding the mystery. Rather, the difference is primarily one of belief concerning the personal identity of Christ. It is a difference in conception of the salvation connected with Christ, that drives all reactions, either favorable or unfavorable, to the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. As it is, the doctrine of the Trinity is directly tied up with Christology.

Orthodox, Roman Catholic and Protestant distinctions

The Western (Roman Catholic) tradition is more prone to make positive statements concerning the relationship of persons in the Trinity. It should be noted that explanations of the Trinity are not the same thing as the doctrine itself; nevertheless the Augustinian west is inclined to think in philosophical terms concerning the rationality of God's being, and is prone on this basis to be more open than the East to seek philosophical formulations which make the doctrine more intelligible.

The Christian East, for its part, correlates ecclesiology and trinitarian doctrine, and seeks to understand the doctrine of the Trinity via the experience of the Church, which it understands to be "an ikon of the Trinity" and therefore, when St. Paul writes concerning Christians that all are "members one of another," Eastern Christians in turn understand this as also applying to the Divine Persons.

For example, one Western explanation is based on deductive assumptions of logical necessity: which hold that God is necessarily a Trinity. On this view, the Son is the Father's perfect conception of his own self. Since existence is among the Father's perfections, his self-conception must also exist. Since the Father is one, there can be but one perfect self-conception: the Son. Thus the Son is begotten, or generated, by the Father in an act of intellectual generation. By contrast, the Holy Spirit proceeds from the perfect love that exists between the Father and the Son: and as in the case of the Son, this love must share the perfection of real existence. Therefore, as reflected in the filioque clause inserted into the Nicene Creed by the Roman Catholic Church, the Holy Spirit is said to proceed from both the Father "and the Son." The Eastern Orthodox church holds that the filioque clause, i.e., the added words "and the Son" (in Latin, filioque), constitutes heresy, or at least profound error. One reason for this is that it undermines the personhood of the Holy Spirit; is there not also perfect love between the Father and the Holy Spirit, and if so, would this love not also share the perfection of real existence? At this rate, there would be an infinite number of persons of the Godhead, unless some persons were subordinate so that their love were less perfect and therefore need not share the perfection of real existence.

Most Protestant groups that use the creed also include the filioque clause. However, the issue is usually not controversial among them because their conception is generally less exact than is discussed above. The clause is often understood by Protestants to mean that the Spirit is sent from the Father, by the Son - a conception which is not controversial in Catholicism or Eastern Orthodoxy, either. Protestantism is harder to describe however, because of its lack of a unified tradition. The Protestant religious climate, which generally eschews any appeal to Tradition, makes it more likely that rejected alternatives to Trinitarianism will be revisited. In some cases these alternatives have been formally adopted, which the Roman Catholic (and its appendages) and Eastern Orthodox churches have rejected as heresies, including a practical tri-theism (the distinction of persons implies a distinction in being), Nestorianism (a distinction in Christ's natures implies a distinction in persons), Sabellianism (or Modalism, the oneness of God implies singleness of person revealed in different ways at various times), Adoptionism or Unitarianism (Which insist Jesus is purely human and began his existence at birth), and Arianism (Jesus pre-existed as an angelic being who created the world, but was not divine, leading to hero-adoration of Jesus, as opposed to religious worship of Jesus as God, and of Christ as God incarnate, and of the Spirit as the presence of God within the believer), etc. In those cases where such alternatives are formally adopted, as opposed to being mistakenly substituted for orthodoxy, Protestantism drops identification with those groups, in effect upholding the Trinitarian Tradition as a biblical doctrine.

Historical development

Because Christianity converts cultures from within, the doctrinal formulas as they have developed bear the marks of the ages through which the church has passed. The rhetorical tools of Greek philosophy, especially of Neoplatonism, are evident in the language adopted to explain the church's rejection of Arianism and Adoptionism on one hand (teaching that Christ is inferior to the Father, or even that he was merely human), and Docetism and Sabellianism on the other hand (teaching that Christ was identical to God the Father, or an illusion). Augustine of Hippo has been noted at the forefront of these formulations; and he contributed much to the speculative development of the doctrine of the Trinity as it is known today, in the West; the Cappadocian Fathers (Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory Nazianzus) are more prominent in the East. The imprint of Augustinianism is found, for example, in the western Athanasian Creed, which, although it bears the name and reproduces the views of the fourth century opponent of Arianism, was probably written much later.

These controversies were for most purposes settled at the Ecumenical councils, whose creeds affirm the doctrine of the Trinity. Constantine the Great who called the first of these councils, the First Council of Nicaea in 325, arguably had political motives for settling the issue rather than religious reasons; as he personally favored the Arian party, which in politically key regions of the Empire held a majority over the Catholics. It was also the form of Christianity that had been adopted by northern tribes of Vandals, and it would have given Constantine an advantage in defense against them, if the council adopted the same faith. It was not to be. The arguments of the deacon Athanasius prevailed; and over the next three hundred years, the Arians were gradually converted to Catholicism.

According to the Athanasian Creed, each of these three divine Persons is said to be eternal, each almighty, none greater or less than another, each God, and yet together being but one God, So are we forbidden by the catholic religion to say; There are three Gods or three Lords. -- Athanasian Creed, line 20

Some feminist theologians refer to the persons of the Holy Trinity with more gender-neutral language, such as Creator, Redeemer, and Sustainer (or Sanctifier). This is a recent formulation, which seeks to redefine the Trinity in terms of three roles in salvation, not eternal identities, personalities, or relationships. Since, however, each of the three divine persons participates in the acts of creation, redemption, and sustaining, traditional Christians reject this formulation as simply a new variety of Modalism.

A more orthodox theology, responding to feminist concerns, might note the following: a)the names "Father" and "Son" are clearly analogical, since all trinitarians would agree that God has no gender per se; b)that, in translating the Creed, for example, "born" and "begotten" are equally valid translations of the Greek word "gennao," which refers to the eternal generation of the Son by the Father: hence, one may refer to God "the Father who gives birth"; this is further supported by patristic writings which compare and contrast the "birth" of the Divine Word "before all ages" (i.e., eternally) from the Father with His birth in time from the Virgin Mary; c)Using "Son" to refer to the Second Divine Person is most proper only when referring to the Incarnate Word, who is Jesus, a human who is clearly male; d)in Semitic languages, such as Hebrew and Aramaic, the noun translated "spirit" is grammatically feminine and the images of the Holy Spirit in Scripture are often feminine as well, as with the Spirit "brooding" over the primordial chaos in Genesis 1 and the image of the Holy Spirit as a dove in the New Testament.

Modalists attempted to resolve the mystery of the Trinity by holding that the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost are merely modes, roles, or manifestations of God Almighty. This anti-trinitarian view contend that the three "Persons" are not distinct Persons, but titles which describe how humanity has interacted with or had experiences with God. In the Role of The Father, God is the provider and creator of all. In the mode of The Son, man experiences God in the flesh, as a human, fully man and fully God. God manifests Himself as the Holy Spirit by his actions on Earth and within the lives of Christians. This view is known as Sabellianism, and was rejected as heresy by the Ecumenical Councils although it is still prevalent today among denominations known as "Oneness" and "Apostolic" Pentecostal Christians, the largest of these sects being the United Pentecostal Church. Trinitarianism insists that the Father, Son and Spirit simultaneously exist, each fully the same God.

The doctrine developed into its present form precisely through this kind of confrontation with alternatives; and the process of refinement continues in the same way. Even now, ecumenical dialogue between Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Roman Catholic, the Assyrian Church of the East and trinitarian Protestants, seeks an expression of trinitarian and christological doctrine which will overcome the extremely subtle differences that have largely contributed to dividing them into separate communities. The doctrine of the Trinity is therefore symbolic, somewhat paradoxically, of both division and unity.

Dissent from the doctrine

Most Christians believe that the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity is so central to the Christian faith, that to deny it is to reject the Christian faith entirely. However a number of nontrinitarian groups, both throughout history and today, identify themselves as Christians but reject the doctrine of the Trinity in any form, arguing that theirs was the original pre-Nicean understanding. Some ancient sects, such as the Ebionites, said that Jesus was not a "Son of God", but rather an ordinary man who was a prophet. Many modern groups also teach a nontrinitarian understanding of God. These include The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Jehovah's Witnesses, the Christadelphians, the Living Church of God, Christian Scientists, the Unification Church, American Unitarian Conference, Branhamists, Frankists, Oneness Pentecostals, Iglesia ni Cristo and the splinter groups of Armstrongism, among others. These groups differ from one another in their view of God, but all alike reject the doctrine of the Trinity.

Criticism of the doctrine includes the argument its "mystery" is essentially an inherent irrationality, where the persons of God are claimed to share completely a single divine substance, the "being of God", and yet not partake of each others' identity. Critics also argue the doctrine, for a teaching described as fundamental, lacks direct scriptural support, and even some proponents of the doctrine acknowledge such direct or formal support is lacking. The New Catholic Encyclopedia, for example, says, "The doctrine of the Holy Trinity is not taught in the Old Testament", and The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia adds, "The doctrine is not explicitly taught in the New Testament", although these sources contend the doctrine is implicit. The scriptural question, however, was sufficiently important to 16th century historical figures such as Michael Servetus as to lead them to argue the question. The Geneva City Council condemned Servetus to be burned at the stake for this, and for his opposition to infant baptism.

Debate over the biblical basis of the doctrine tends to revolve chiefly over the question of the deity of Jesus (see Christology). Proponents find plurality in Old Testament details like the term "Elohim" and argue for example that Jesus accepted worship, forgave sins, claimed oneness with the Father, and used the expression "I am" as an echo of the divine name given to Moses on Sinai. Those who reject the teaching for their part offer different explanations, arguing among other things that Jesus also rejected being called so little as good in deference to God (versus "the Father"), disavowed omniscience as the Son, and referred to ascending unto "my Father, and to your Father; and to my God, and to your God". They also dispute that "Elohim" denotes plurality, noting that this name in nearly all circumstances takes a singular verb and arguing that where it seems to suggest plurality, Hebrew grammar still indicates against it. They also point to statements by Jesus such as his declaration that the Father was greater than he or that he was not omniscient, in his statement that of a final day and hour not even he knew, but the Father. In Theological Studies #26 (1965) p.545-73, Does the NT call Jesus God?, Raymond E. Brown wrote that Mk10:18, Lk18:19, Mt19:17, Mk15:34, Mt27:46, Jn20:17, Eph1:17, 2Cor1:3, 1Pt1:3, Jn17:3, 1Cor8:6, Eph4:4-6, 1Cor12:4-6, 2Cor13:14, 1Tm2:5, Jn14:28, Mk13:32, Ph2:5-10, 1Cor15:24-28 are "texts that seem to imply that the title God was not used for Jesus" and are "negative evidence which is often somewhat neglected in Catholic treatments of the subject."

Trinitarians claim that these statements are summed up in the fact that Jesus existed as the Son of God in the human flesh. Thus he is both God and man, who became "lower than the angels, for our sake" (Hebrews 2:6-8, Pslam 8:4-6) and who was tempted as humans are tempted, but he did not sin (Hebrews 4:14-16).

The teaching is also pivotal to ecumenical disagreements with two of the other major faiths, Judaism and Islam; the former reject Jesus' divine mission entirely, the latter accepts Jesus as a human prophet just like Muhammad but rejects altogether the deity of Jesus. Many within Judaism and Islam also accuse Christian trinitarians of practicing polytheism, of believing in three gods rather than just one. Islam holds that because Allah is unique and absolute (the concept of tawhid) the Trinity is impossible and has even been condemned as polytheistic. This is emphasised in the Qur'an which states "He (Allah) does not beget, nor is He begotten, And (there is) none like Him." (Qur'an, 112:1-4)

Other Views of the Trinity

There have been numerous other views of the relations of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit; the most prominent include:

- Ebionites believed that the Son was subordinate to the Father and nothing more than a special human.

- Marcion Who believed that there were two Deities, one of Creation / Hebrew Bible and one of the New Testament.

- Arius Who believed that the Son was subordinate to the Father, firstborn of all Creation. However, the Son did have Divine status. (see also Nicene Creed)

- Modalism states that God has taken numerous forms in both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, and that Jesus was no different than the burning bush that appeared to Moses.

- Eutychianism holds that the divinity of the Son became human and the human became divine. Orthodox Trinitarianism holds these parts of the Son distinct.

- Latter-day Saints, aka "Mormons," hold that the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost are three separate and distinct individuals [1], but can and do act together as one Godhead, a single and unified administrative unit. The Latter-day Saint doctrine on the Godhead draws on the circumstances surrounding events that include the baptism of Jesus [2] and the First Vision of the Prophet Joseph Smith [3].

- Docetism holds that the Son is not human, but wholly and only divine.

- Adoptionism holds that Jesus was chosen on the event of his baptism to be anointed by the Holy Spirit and became divine upon resurrection.

- Rastafarians are the only non-Christian group to theorise about the Holy Trinity.

Theory of pagan origin and influence

Nontrinitarian "Christians" have long contended that the doctrine of the Trinity is a prime example of Christian borrowing from pagan sources. According to this view, a simpler idea of God was lost very early in the history of the Church, through accommodation to pagan ideas, and the "incomprehensible" doctrine of the Trinity took its place. As evidence of this process, a comparison is often drawn between the Trinity and notions of a divine triad, found in pagan religions and Hinduism. Modern Hinduism has a triad, i.e., Trimurti.

As far back as Babylonia, the worship of pagan gods grouped in threes, or triads, was common. That influence was also prevalent in Egypt, Greece, and Rome in the centuries before, during, and after Christ. After the death of the apostles, many nontrinitarians contend that these pagan beliefs began to invade Christianity. (First and second century Christian writings reflect a certain belief that Jesus was one with God the Father, but anti-Trinitarians contend it was at this point that the nature of the oneness evolved from pervasive coexistence to identity.)

Some find a direct link between the doctrine of the Trinity, and the Egyptian theologians of Alexandria, for example. They suggest that Alexandrian theology, with its strong emphasis on the deity of Christ, was an intermediary between the Egyptian religious heritage and Christianity.

The Church is charged with adopting these pagan tenets, invented by the Egyptians and adapted to Christian thinking by means of Greek philosophy. As evidence of this, critics of the doctrine point to the widely acknowledged synthesis of Christianity with platonic philosophy, which is evident in Trinitarian formulas that appeared by the end of the third century. Catholic doctrine became firmly rooted in the soil of Hellenism; and thus an essentially pagan idea was forcibly imposed on the churches beginning with the Constantinian period. At the same time, neo-Platonic trinities, such as that of the One, the Nous and the Soul, are not a trinity of consubstantial equals as in orthodox Christianity.

Nontrinitarians assert that Catholics must have recognized the pagan roots of the trinity, because the allegation of borrowing was raised by some disputants during the time that the Nicene doctrine was being formalized and adopted by the bishops. For example, in the 4th Century Catholic Bishop Marcellus of Ancyra's writings, On the Holy Church,9 :

"Now with the heresy of the Ariomaniacs, which has corrupted the Church of God...These then teach three hypostases, just as Valentinus the heresiarch first invented in the book entitled by him 'On the Three Natures'. For he was the first to invent three hypostases and three persons of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, and he is discovered to have filched this from Hermes and Plato." (Source: Logan A. Marcellus of Ancyra (Pseudo-Anthimus), 'On the Holy Church': Text, Translation and Commentary. Verses 8-9. Journal of Theological Studies, NS, Volume 51, Pt. 1, April 2000, p.95 ).

Such a late date for a key term of Nicene Christianity, and attributed to a Gnostic, they believe, lends credibility to the charge of pagan borrowing. Marcellus was rejected by the Catholic Church for teaching a form of Sabellianism.

The early apologists, including Justin Martyr, Tertullian and Irenaeus, frequently discussed the parallels and contrasts between Christianity and the pagan and syncretic religions, and answered charges of borrowing from paganism in their apologetical writings.

Christian life and the Blessed Trinity

The singleness of God's being and the multiplicity of the Divine Persons together account for the nature of Christian salvation, and disclose the gift of eternal life. "Through the Son we have access to the Father in one Spirit" (Ephesians 2:18). Communion with the Father is the goal of the Christian faith and is eternal life. It is given to humans through the Divine union with humanity in Jesus Christ who, although fully God, died for sinners "in the flesh" to accomplish their redemption, and this forgiveness, restoration, and friendship with God is made accessible through the gift to the Church of the Holy Spirit, who, being God, knows the Divine Essence intimately and leads and empowers the Christian to fulfill the will of God. Thus, this doctrine touches on every aspect of the trinitarian Christian's faith and life; and this explains why it has been so earnestly contended for, throughout Christian history. In fact, while the oldest traditions hold that it is impossible to speculate concerning the being of God (see apophatic theology), yet those same traditions are particularly attentive to Trinitarian formulations, so basic to mere Christian faith is this doctrine considered to be.

Similarities in the 16th Century Jewish Kabbalah

In the late Kabbalistic tradition, originating in the city of Safed in the 16th century, an essential part of representations of the Tree of life or Etz Hayim is a set of three vertical lines of light, each line being headed by Sefirot, or degrees of altruistic quality at the top. These three Sefirot form a spiritual or heavenly triangle, which rules the whole earthly part of the Tree of Life. It is obvious that Sefirot of Kether (Crown), Chochmah (Wisdom) and Binah (Understanding), i.e. Ancient One, Father and Mother, or even Chochmah, Binah and Tiphereth (Glory) as Son also have much similarity with a secret of Trinity. These three lines (sheloshah kavim) are an essential and very deep spiritual secret of Torah (Torath ha-Sod). Priority, importance and secrecy of Trinity and sheloshah kavim (three lines) is obviously similar. According to kabbalah through these mysterious lines—kav smol, kav yamin and kav emtsa'i—Heaven rules the soul's wishes and destiny.

Due in part to the apparent similarities between these Kabbalistic teachings and the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, Christian disputationalists sometimes attempted to use Kabbalah to convince Jews to convert to Christianity, and encouraged Christians to study Kabbalah in the belief that this would help them to do so. Needless to say, not many Jews were so convinced, and Jewish Kabbalists believe that, even though superficial similarities exist between the Christian Trinity and some parts of Kabbalah, these are distinct beliefs and properly understood one does not imply the other.

In popular culture

In the Valérian comics, the Trinity appeared as a tough, street-hardened police sergeant (Father), a hippie (Son) and a broken jukebox (Holy Spirit).

In the Fritz Lang film Metropolis, the city mayor Joh Fredersen represents the Father and the humble city proletariat as the Holy Spirit. The son of the mayor, Freder Fredersen, represents the Son. The film ends in statement: The intermediator between brain [Father] and hands [Holy Spirit] is Heart (Son).

Also, in Postcolonial Theory, 'The Holy Trinity'is a term coined by a Senior Lecturer at the University of Leeds, Dr John McLeod, with regards to the three main postcolonial theorists whose work constitutes much of the debate in this thriving and controversial field of study; Edward Said, Homi K Bhabha and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. (Mcleod, John, Beginning Postcolonialism, Manchester University Press, 2000)

See also

External links

General

- "Doctrine of the Trinity". ReligionFacts, 2005. (ed. Overview of history, doctrinal statements and critics of the doctrine of the Trinity).

- "A Public Discussion on the Doctrine of the Trinity". (ed. A reprint of a debate that occurred in 1832 between Frederick Plummer and William McAlla).

Trinitarian

- Boguslawski, Alexander, "The Hospitality of Abraham. 2005. (ed., Andrei Rublev's icon of the "Old Testament Trinity", with discussion of the history of the Trinity in iconography.)

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, chapter on the Creed.

- Jesus' Divinity Within Jewish Monotheism by Christopher Price

- The Holy Trinity Extensive Collection of Essays on the Trinity by Monergism.com

- Trinity – an evangelical view

Anti-Trinitarian

- Binitarian View: One God, Two Beings Before the Beginning- A Church of God (Armstrong) view

- "The Author of the Atonement" chapter from "The Atonement Between God and Man" by Charles Taze Russell - Jehovah's Witness view

- "The Oneness of God" by David K. Bernard (Series in Pentecostal Theology, Volume 1) - Oneness Pentecostal view

- Christology - Christadelphian view

- Should you believe in the Trinity? - Jehovah's Witness view