Iliad

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

The Iliad (Template:Lang-el, Iliás) is an epic creation recounting significant events during a portion of the final year of the Trojan War — the Greek siege of the city of Ilion (Troy) — hence the title (“pertaining to Ilion”). In twenty-four scrolls, containing 15,693 lines of dactylic hexameter, it tells the wrathful withdrawal from battle of Achilles, the premiere Greek warrior, after King Agamemnon dishonoured him — an internecine quarrel disastrous to the Greek cause. This poem establishes most of the events (including Achilles’s slaying of Hector) later developed in the Epic Cycle narrative poems recounting the Trojan War events not narrated in the Iliad and the Odyssey.[1]

The Iliad and its sequel, the Odyssey, are attributed to Homer, but his sole authorship is doubted by some scholars who think the poems exhibit different poetic styles (dialect, idiom, metre) which may indicate several authors, a presumed characteristic of the Ancient Greek oral tradition. [2] Twentieth century scholars dated these poems to the late-ninth and early-eighth centuries BC, [3] notably G. S. Kirk, Richard Janko, and Barry B. Powell (who links its transcription to the invention of the Greek alphabet); however, Martin West and Richard Seaford, posit either the seventh or the sixth centuries BC, as the composition time(s) of this oldest extant literary work of Ancient Greece.

Story

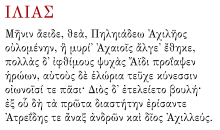

The Iliad begins thus:

Template:Polytonic

Sing, goddess, the rage of Achilles the son of Peleus,

the destructive rage that sent countless ills on the Achaeans...

The poem’s first word, Template:Polytonic (mēnis) — wrath — establishes the principal theme of the Iliad: the Wrath of Achilles. [4] At the story’s start, the Greeks quarrel about returning Chryseis, a Trojan war-prize of King Agamemnon, to her father, Chryses, an Apollonian priest. When Agamemnon, the Mycenaen King and commander of the Greeks invading Troy, refuses with a threat to ransom the girl to her father, the offended Apollo plagues them with pestilence. At an Achilles-convoked assembly, the Greeks compel Agamemnon’s returning Chryseis to appease Apollo and end the pestilence; he reluctantly agrees, but, in her stead, takes Briseis, Achilles’s war-prize concubine. Dishonoured, Achilles wrathfully withdraws himself, and his Myrmidon warriors, from the war.

Thematically analogous to Achilles’s hubris is Hector’s nobility, as Trojan prince, husband, and father, defending country, kith and kin. With Achilles out of battle, Hector successfully breaches the fortified Greek camp at the Trojan shore, wounding Odysseus and Diomedes; the gods are favoring the Trojans. When they threaten to set the Greek ships afire, Patroclus dresses in Achilles’ armor to lead the Myrmidons in repelling the Trojans. [5] In battle, Hector kills the disguised Patroclus, thinking him Achilles. In revenge, Achilles slays Hector in single combat, then defiles his corpse for days, until King Priam, aided by Hermes, recovers Hector’s corpse from Achilles, who pitying the bereaved king, empathetically consents. Hector’s funeral ends the Iliad.

Homeric warfare is brutal, bloody, and mean; names, detailed battle descriptions, taunts and war cries convey the immediacy of combat, wounds, and death. A warrior’s death merely aggravates the violence, as the sides battle for booty (armour, corpses) and revenge, which, in turn, motivate the comrades of the dead to cycles of punitive attack and counterattack; the fortunate escape death by friendly charioteers and divine intervention. The Iliad features strong supernaturalism (religion): the Greek and Trojan folk are pious, their armies manned with divinely-descended heroes. They consult prophets and priests in deciding their actions with sacrifices to the gods — who join in battle, fighting mortal and immortal, whilst advising and protecting their human favorites.

The characters of the Iliad relate the Trojan War to Greece’s other myths — Jason and the Argonauts, the Seven Against Thebes, the Labors of Hercules, et cetera — of which there exist versions, thus, Homer’s dramatic licence fitting character and event to narrative. The poem tells only of the final weeks of the war’s concluding tenth year, it tells neither of its provocation — Paris abducting Helen from her husband, Menelaus, King of Sparta — nor of its first nine years, nor of its ending with Achilles’s death and the fall of Troy. Those matters are subject of the Epic Cycle poems — the Theogonia and Titanomachia, about the world’s creation and early history; the Cypria, about Helen’s abduction; the Aethiopis, Ilias Parva, Iliu Persis, and Nostoi, continuations of the Iliad; and the Telegonia, about the death of Odysseus — which exist as literary fragments dating between the seventh and sixth centuries BC. [6]

The Books

The division of Homer's epics into twenty-four books each is a matter of some controversy:

There is no positive evidence that the division . . . was made before the Alexandrian period. In the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. several authors refer to episodes or sections of both poems by titles . . . such titles did not correspond to our book divisions, and taken by itself this tends to suggest either that the division was not yet made, or that if it was, it was not so widely used as to effect the older division by episodes . . . it has been suggested that the innovation made by the Alexandrian scholars was not the division into books, but simply the use of letters of the alphabet for them, the division itself being older. Those who prefer an earlier date . . . tend to associate it with rhapsodic practice, and the use of the term ῥαψῳδια for a book might support this[7]

- Book 1: After nine years of the Trojan War, King Agamemnon seizes Briseis, Achilles’s war-concubine, for having relinquished Chryseis; dishonoured, Achilles wrathfully withdraws; the gods argue the War’s outcome.

- Book 2: Testing Greek resolve, Agamemnon feigns a homeward order; Odysseus encourages the Greeks to pursue the fight; see the “Catalogue of Ships” and the “Catalogue of Trojans and Allies”.

- Book 3: In a truce, Paris and Menelaus meet in single combat for Helen, while she and King Priam watch from the city; Aphrodite rescues the over-matched Paris, yet Menelaus is the victor.

- Book 4: The Greek-favouring Athena provokes a Trojan truce-breaking and battle begins.

- Book 5: In his aristeia (battle supremacy), Diomedes, aided by Athena, wounds Aphrodite and Ares.

- Book 6: Glaucus and Diomedes do not fight each other, and swap armour; at Troy, Hector bids farewell to his wife, Andromache, and their son.[8]

- Book 7: Hector battles Ajax; Paris offers restitution — but not Helen.

- Book 8: Zeus orders divine withdrawal; Hera and Athena defy him; the war favours Troy.

- Book 9: The “Embassy to Achilles”: Agamemnon sends Odysseus, Ajax, and Phoenix to Achilles for help, who spurns the offered honours and riches.

- Book 10: The “Doloneia”: Diomedes and Odysseus kill the Trojan Dolon, and effect a night raid against a Thracian camp.

- Book 11: Paris wounds Diomedes; Achilles has Patroclus enquire about the fight’s progress; Nestor begs for the Myrmidons.

- Book 12: Led by Hector, the Trojans breach the Greek camp walls.

- Book 13: Contravening Zeus’s order, Poseidon rallies the Greeks.

- Book 14: With the “Deception of Zeus”, Hera helps Poseidon assist the Greeks to repel the Trojans; Hector is wounded.

- Book 15: Zeus stops Poseidon; Apollo rouses Hector set the Greek ships afire.

- Book 16: Patroclus says "But you have been impracticable Achilles . . . at least send me out speedily". Achilles replies "put my renowned armour on your shoulders and lead out the battle-loving Myrmidons to fight". Patroclus proceeds to repel the Trojans; he kills Sarpedon; Hector kills Patroclus.

- Book 17: Hector strips Patroclus of Achilles’s armour; Menelaus and the Greeks recover Patroclus’s corpse. (books XVI and XVII constitute the “Patrocleia”).

- Book 18: Achilles seeks to avenge Patroclus; Hephaestus forges a new “Shield of Achilles”.

- Book 19: Agamemnon and Achilles reconcile; he joins battle, despite his deadly fate.

- Book 20: The gods join the battle; Achilles drives all the Trojans before him.

- Book 21: Achilles routs the Trojans, and battles the river Scamander; Apollo leads him astray.

- Book 22: Achilles kills Hector outside the walls of Troy, dragging the corpse to the Greek camp. [8]

- Book 23: Funereal games celebrate Patroclus; twelve Trojan youths are burned with the corpse.

- Book 24: King Priam secretly enters the Greek camp, begging Achilles for Hector’s corpse, who consents; at the funeral pyre, Helen and Andromache comment upon the war.

Notable passages

- The Catalogue of Ships (Book II, lines 494-759)

- The Teichoscopia (Book III, lines 121-244)

- The Deception of Zeus (Book XIV, lines 153-353)

- The Shield of Achilles (Book XVIII, lines 430-617)

After the Iliad

The Iliad foreshadows events subsequent to Hector’s funeral, conveying Troy’s doom; see the Trojan War for its story, as developed in later Græco–Roman poetry and drama; the Odyssey narrates Odysseus’s decade-long journey home to Ithaca. The poems incorporate overlapping past and future references, and, despite their narrow scopes, are a complete thematic exploration of the Trojan War.

The major characters

- See also: Category: Deities in the Iliad

The many characters of the Iliad are catalogued; the latter-half of Book II, the “Catalogue of Ships”, lists commanders and cohorts; battle scenes feature quickly-slain minor characters.

- The Achaeans (Template:Polytonic) — aka the Hellenes (Greeks), Danaans (Δαναοί), and Argives (Ἀργεĩοι).

- Agamemnon — King of Mycenae; leader of the Greeks.

- Achilles — King of the Myrmidons.

- Odysseus — King of Ithaca; the wiliest Greek commander, and hero of the Odyssey.

- Aias (Ajax the Greater) — son of Telamon, with Diomedes, he is second to Achilles in martial prowess.

- Menelaus — King of Sparta; husband of Helen.

- Diomedes — son of Tydeus, King of Argos.

- Aias (Ajax the Lesser) — son of Oileus, often partner of Ajax the Greater.

- The Trojan men

- Hector — son of King Priam; the foremost Trojan warrior.

- Aeneas — son of Anchises and Aphrodite.

- Deiphobus — brother of Hector and Paris.

- Paris — Helen’s lover-abductor.

- Priam — the aged King of Troy.

- Polydamas — a prudent commander whose advice is ignored; he is Hector’s foil.

- Agenor — a Trojan warrior who attempts to fight Achilles (Book XXI).

- Dolon (Template:Polytonic) — a spy upon the Greek camp (Book X).

- Antenor — King Priam’s advisor, who argues for returning Helen to end the war; Paris refuses.

- Polydorus — son of Priam and Laothoe.

- The Trojan women

- Hecuba (Template:Polytonic) — Priam’s wife; mother of Hector, Cassandra, Paris, and others.

- Helen (Template:Polytonic) — Menelaus’s wife; espoused first to Paris, then to Deiphobus.

- Andromache (Template:Polytonic) — Hector’s wife; mother of Astyanax (Template:Polytonic)

- Cassandra (Template:Polytonic) — Priam’s daughter; courted by Apollo, who bestows the gift of prophecy to her; upon her rejection, he curses her, and her warnings of Trojan doom go unheeded.

These Olympic deities advise and manipulate the humans; excepting Zeus, they fight the Trojan War. (See Theomachy.)

Themes: the substance of heroism

Nostos

Nostos (νόστος — homecoming) occurs seven times in the poem (II.155, II.251, IX.413, IX.434, IX.622, X.509, XVI.82); thematically, the concept of homecoming is much explored in Ancient Greek literature, especially in the post-war homeward fortunes experienced by Atreidae, Agamemnon, and Odysseus (see the Odyssey), thus, nostos is impossible without sacking Troy — King Agamemnon’s motive for winning, at any cost.

Kleos

Kleos (κλέος — glory, fame) is the concept of glory earned in heroic battle; [1] for most of the Greek invaders of Troy, notably Odysseus, kleos is earned in a victorious nostos (homecoming), yet not for Achilles, he must choose one reward, either nostos or kleos. [2] In Book IX (IX.410–16), he poignantly tells Agamemnon’s envoys — Odysseus, Phoenix, Ajax — begging his reinstatement to battle about having to choose between two fates (διχθαδίας κήρας — 9.411). [3]

The passage reads:

μήτηρ γάρ τέ μέ φησι θεὰ Θέτις ἀργυρόπεζα (410)

διχθαδίας κῆρας φερέμεν θανάτοιο τέλος δέ.

εἰ μέν κ’ αὖθι μένων Τρώων πόλιν ἀμφιμάχωμαι,

ὤλετο μέν μοι νόστος, ἀτὰρ κλέος ἄφθιτον ἔσται

εἰ δέ κεν οἴκαδ’ ἵκωμι φίλην ἐς πατρίδα γαῖαν,

ὤλετό μοι κλέος ἐσθλόν, ἐπὶ δηρὸν δέ μοι αἰὼν (415)

ἔσσεται, οὐδέ κέ μ’ ὦκα τέλος θανάτοιο κιχείη. [9]

Richmond Lattimore translates:

For my mother Thetis the goddess of silver feet tells me

I carry two sorts of destiny toward the day of my death. Either,

if I stay here and fight beside the city of the Trojans,

my return home is gone, but my glory shall be everlasting;

but if I return home to the beloved land of my fathers,

the excellence of my glory is gone, but there will be a long life

left for me, and my end in death will not come to me quickly.

[10]

In foregoing his nostos, he will earn the greater reward of kleos aphthiton (κλέος ἄφθιτον — fame imperishable). [4] In the poem, aphthiton (ἄφθιτον — imperishable) occurs five times (II.46, V.724, XIII.22, XIV.238, XVIII.370), each occurrence denotes an object (i.e. Agamemnon’s sceptre, the wheel of Hebe’s chariot, the house of Poseidon, the throne of Zeus, the house of Hephaistos); translator Lattimore renders kleos aphthiton as forever immortal and as forever imperishable — connoting Achilles’s mortality by underscoring his greater reward in returning to battle Troy.

Timê

Akin to kleos is timê (тιμή — respect, honour), the concept denoting the respectability an honourable man accrues with accomplishment (cultural, political, martial), per his station in life. In Book I, the Greek troubles begin with King Agamemnon’s dishonourable, unkingly behaviour — first, by threatening the priest Chryses (1.11), then, by aggravating them in disrespecting Achilles, by confiscating Bryseis from him (1.171). The warrior’s consequent rancour against the dishonourable king ruins the Greek military cause.

Wrath

The poem’s initial word, μῆνιν (mēnin — wrath, rage, fury), establishes the Iliad’s principal theme: The Wrath of Achilles. [11] His personal rage and wounded soldier’s vanity propel the story — the Greeks’ faltering in battle, the slayings of Patroclus and Hector, and the fall of Troy. In Book I, the Wrath of Achilles first emerges in the Achilles-convoked meeting, between the Greek kings and Calchas, the Seer. King Agamemnon dishonours Chryses, the Trojan Apollonian priest, by refusing with a threat the restitution of his daughter, Chryseis — despite the proffered ransom of “gifts beyond count”; [12] the insulted priest prays his god’s help — and a nine-day rain of arrows falls upon the Greeks. Moreover, in that meeting, Achilles accuses Agamemnon of being “greediest for gain of all men”. [13] To that, Agamemnon replies:

But here is my threat to you.

Even as Phoibos Apollo is taking away my Chryseis.

I shall convey her back in my own ship, with my own

followers; but I shall take the fair-cheeked Briseis,

your prize, I myself going to your shelter, that you may learn well

how much greater I am than you, and another man may shrink back

from likening himself to me and contending against me. [14]

After that, only Athena stays Achilles’s wrath. He vows to never again to obey orders from Agamemnon. Furious, Achilles cries to his mother, Thetis, who persuades Zeus’s divine intervention — favouring the Trojans — until Achilles’s rights are restored. Meanwhile, Hector leads the Trojans to almost pushing the Greeks back to the sea (Book XII); later, Agamemnon contemplates defeat and retreat to Greece (Book XIV). Again, the Wrath of Achilles turns the war’s tide in seeking vengeance when Hector kills Patroclus. Aggrieved, Achilles tears his hair and dirties his face; Thetis comforts her mourning son, who tells her:

So it was here that the lord of men Agamemnon angered me.

Still, we will let all this be a thing of the past, and for all our

sorrow beat down by force the anger deeply within us.

Now I shall go, to overtake that killer of a dear life,

Hektor; then I will accept my own death, at whatever

time Zeus wishes to bring it about, and the other immortals.[15]

Accepting prospective death as fair price for avenging Patroclus, he returns to battle, dooming Hector and Troy, thrice chasing him ’round the Trojan walls, before slaying him, then dragging the corpse behind his chariot, back to camp.

Fate

Fate (κήρα — destiny, fate) propels most of the events of the Iliad. Once set, gods and men abide it, neither truly able nor willing to contest it. How fate is set is unknown, but it is told by the Fates and Seers such as Calchas. Men and their gods continually speak of heroic acceptance and cowardly avoidance of one’s slated fate.[16] Yet, it does not determine every action, incident, and occurrence, but does determine the outcome of life — before killing him, Hector calls Patroclus a fool for cowardly avoidance of his fate, by attempting his defeat; Patroclus retorts: [17]

No, deadly destiny, with the son of Leto, has killed me,

and of men it was Euphorbos; you are only my third slayer.

And put away in your heart this other thing that I tell you.

You yourself are not one who shall live long, but now already

death and powerful destiny are standing beside you,

to go down under the hands of Aiakos’ great son, Achilleus.[18]

Here, Patroclus alludes to fated death by Hector’s hand, and Hector’s fated death by Achilles’s hand. Despite free will, each accepts the outcome of his life, yet, no-one knows if the gods can alter fate. The first instance of this doubt occurs in Book XVI; seeing Patroclus about to kill Sarpedon, his mortal son, Zeus says:

Ah me, that it is destined that the dearest of men, Sarpedon,

must go down under the hands of Menoitios’ son Patroclus.[19]

About his dilemma, Hera asks Zeus:

Majesty, son of Kronos, what sort of thing have you spoken?

Do you wish to bring back a man who is mortal, one long since

doomed by his destiny, from ill-sounding death and release him?

Do it, then; but not all the rest of us gods shall approve you.[20]

In deciding — between losing a son or abiding fate — Zeus, the King of the Gods, allows it. This motif recurs when he considers sparing Hector, whom he loves and respects. Again, Athena asks him:

Father of the shining bold, dark misted, what is this you said?

Do you wish to bring back a man who is mortal, one long since

doomed by his destiny, from ill-sounding death and release him?

Do it, then; but not all the rest of us gods shall approve you.[21]

Again, Zeus appears capable of altering fate, but does not, deciding instead to abide set outcomes; yet, contrariwise, fate spares Aeneas, after Apollo convinces the over-matched Trojan to fight Achilles. Poseidon cautiously speaks:

But come, let us ourselves get him away from death, for fear

the son of Kronos may be angered if now Achilleus

kills this man. It is destined that he shall be the survivor,

that the generation of Dardanos shall not die. . . . [22]

Divinely-aided, Aeneas escapes the wrath of Achilles and survives the Trojan War. Whether or not the gods can alter fate, they do abide it, despite its countering their human allegiances, thus, the mysterious origin of fate is a power beyond the gods. Fate implies the primeval, tripartite division of the world that Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades effected in deposing their father, Cronus, for its dominion. Zeus took the Air and the Sky, Poseidon the Waters, and Hades the Underworld, the land of the dead — yet, they share dominion of the Earth. Despite the earthly powers of the Olympic gods, only the Three Fates set the destiny of Man.

The Iliad as oral tradition

In antiquity, the Greeks applied the Iliad and the Odyssey as the bases of pedagogy; literature central to the educational-cultural function of the itinerant rhapsode, who composed consistent epic poems from memory and improvisation, and disseminated them, via song and chant, in his travels and at the Panathenaic Festival of athletics, music, poetics, and sacrifice, celebrating Athena’s birthday. [23]

Originally, Classical scholars treated the Iliad and the Odyssey as written poetry, and Homer as a writer, yet, by the 1920s, Milman Parry (1902–1935) demonstrated otherwise; his investigation of the oral Homeric style — stock epithets and reiteration (words, phrases, stanzas) — established those formulae as oral tradition artefacts easily applied to an hexametric line; a two-word stock epithet (e.g. “resourceful Odysseus”) reiteration complements a character name by filling a half-line, thus, freeing the poet to compose a half-line of original formulaic text to complete his meaning. [24] In Yugoslavia, Parry and his assistant, Albert Lord (1912–1991), studied the oral-formulaic composition of Bosniac oral poetry, yielding the Parry/Lord thesis that established Oral tradition studies, later developed by Eric Havelock, Marshall McLuhan, Walter Ong, et al.

In The Singer of Tales (1960), Lord demonstrates likeness between the tragedies of the Greek Patroclus, in the Iliad, and of the Sumerian Enkidu, in the Epic of Gilgamesh, and refutes, with “careful analysis of the repetition of thematic patterns”, that the Patroclus storyline upsets Homer’s established compositional formulae of “wrath, bride-stealing, and rescue”, thus, stock-phrase reiteration does not restrict his originality in fitting story to rhyme. [25][26] Like-wise, in The Arming Motif, Prof. James Armstrong reports that the poem’s formulae yield richer meaning because the “arming motif” diction — describing Achilles, Agamemnon, Paris, and Patroclus — serves to “heighten the importance of . . . an impressive moment”, thus, reiteration “creates an atmosphere of smoothness”, wherein, Homer distinguishes Patroclus from Achilles, and foreshadows the former’s death with positive and negative turns of phrase. [27] [28]

In the Iliad, occasional syntactic inconsistency is an oral tradition effect — for example, Aphrodite is “laughter-loving”, despite being painfully wounded by Diomedes (Book V, 375); and the divine representations, mixing Mycenaean and Greek Dark Age (ca. 1150–800 BC) mythologies, parallel the hereditary basilee nobles (lower social rank rulers) with minor Olympic gods, such as Scamander et al. [29]

The relationship between Achilles and Patroclus

Classical-era, historical, and contemporary scholars have questioned the true nature of the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus, arguing that the evidence is equivocal for perceiving and defining it as either platonic or homosexual, although Aeschylus does portray them so in Fragment 134a. [30] Necessarily, critics perceive and interpret that manly relationship with their own mores (social, cultural, sexual), thus, fifth-century BC Athenian scholars perceived it as pederastic (then an accepted male relationship), like-wise the others perceived it as either a platonic warrior-bond or as a homosexual pairing of like-age men — despite Homer’s description of Trojan women as war prizes, hence, the sexual-orientation speculation evinced by Achilles’s outrage at King Agamemnon’s confiscation of Bryseis, his war-prize concubine.[31]

Warfare in the Iliad

Despite Mycenae and Troy being maritime powers, the Iliad features no sea battles. [32] So, the Trojan shipwright (of the ship that transported Helen to Troy), Phereclus, fights afoot, as an infantryman. [33] The battle dress and armour of hero and soldier are well-described. They enter battle in chariots, launching javelins into the enemy formations, then dismount — for hand-to-hand combat with sword and a shoulder-borne hoplon (shield). [34] The Ajax the Greater, son of Telamon, sports a large, rectangular shield (σάκος) with which he protects himself and Teucer, his brother:

- Ninth came Teucer, stretching his curved bow.

- He stood beneath the shield of Ajax, son of Telamon.

- As Ajax cautiously pulled his shield aside,

- Teucer would peer out quickly, shoot off an arrow,

- hit someone in the crowd, dropping that soldier

- right where he stood, ending his life—then he’d duck back,

- crouching down by Ajax, like a child beside its mother.

- Ajax would then conceal him with his shining shield.

- (Iliad 8.267–72, Ian Johnston, translator)

Ajax’s cumbersome shield is more suitable for defence than for offence, while his cousin, Achilles, ports a large, rounded, octagonal shield that he successfully deploys along with his spear against the Trojans:

- Just as a man constructs a wall for some high house,

- using well-fitted stones to keep out forceful winds,

- that’s how close their helmets and bossed shields lined up,

- shield pressing against shield, helmet against helmet

- man against man. On the bright ridges of the helmets,

- horsehair plumes touched when warriors moved their heads.

- That's how close they were to one another.

- (Iliad 16.213–7, Ian Johnston, translator)

In describing infantry combat, Homer names the phalanx formation, [35] but, most scholars do not believe the historical Trojan War was so fought. [36] In the Bronze Age, the chariot was the main battle transport-weapon (e.g. the Battle of Kadesh). The available evidence, from the Dendra armour and the Pylos Palace paintings, indicate the Mycenaeans used two-man chariots, with a long-spear-armed principal rider, unlike the three-man Hittite chariots with short-spear-armed riders, and unlike the arrow-armed Egyptian and Assyrian two-man chariots. Nestor spearheads his troops with chariots; he advises them:

- In your eagerness to engage the Trojans,

- don’t any of you charge ahead of others,

- trusting in your strength and horsemanship.

- And don’t lag behind. That will hurt our charge.

- Any man whose chariot confronts an enemy’s

- should thrust with his spear at him from there.

- That’s the most effective tactic, the way

- men wiped out city strongholds long ago —

- their chests full of that style and spirit.

- (Iliad 4.301–09, Ian Johnston, translator)

Mythologic characters

In the literary Trojan War of the Iliad, the Olympic gods, goddesses, and demigods fight and play great roles in human warfare. Unlike practical Greek religious observance, Homer’s portrayals of them suited his narrative purpose, being very different from the polytheistic ideals Greek society used. To wit, the Classical-era historian Herodotus says that Homer, and his contemporary, the poet Hesiod, were the first artists to name and describe their appearance and characters. [37]

In Greek Gods, Human Lives: What We Can Learn From Myths, Mary Lefkowitz discusses the relevance of divine action in the Iliad, attempting to answer the question of whether or not divine intervention is a discrete occurrence (for its own sake), or if such godly behaviours are mere human character metaphors. The intellectual interest of Classic-era authors, such as Thucydides and Plato, was limited to their utility as “a way of talking about human life rather than a description or a truth”, because, if the gods remain religious figures, rather than human metaphors, their “existence” — without the foundation of either dogma or a bible of faiths — then allowed Greek culture the intellectual breadth and freedom to conjure gods fitting any religious function they required as a people. [38][39]

The Iliad in the arts and literature

Subjects from the Trojan War were a favourite among ancient Greek dramatists. Aeschylus' trilogy, the Oresteia, comprising Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, and The Eumenides, follows the story of Agamemnon after his return from the war.

William Shakespeare used the plot of the Iliad as source material for his play Troilus and Cressida, but focused on a medieval legend, the love story of Troilus, son of King Priam of Troy, and Cressida, daughter of the Trojan soothsayer Calchas. The play, often considered to be a comedy, reverses traditional views on events of the Trojan War and depicts Achilles as a coward, Ajax as a dull, unthinking mercenary, etc.

Robert Browning's poem Development discusses his childhood introduction to the matter of the Iliad and his delight in the epic, as well as contemporary debates about its authorship.

Simone Weil wrote the essay The Iliad or the Poem of Force in 1939 shortly after the commencement of WWII. Its been claimned the essay describes how the Iliad demonstrates the way force, excercised to the extreme in war, reduces both victim and aggressor to the level of the slave and the unthinking automaton. [40]

The 1954 Broadway musical The Golden Apple by librettist John Treville Latouche and composer Jerome Moross was freely adapted from the Iliad and the Odyssey, re-setting the action to America's Washington state in the years after the Spanish-American War, with events inspired by the Iliad in Act One and events inspired by the Odyssey in Act Two.

Christa Wolf's 1983 novel Kassandra is a critical engagement with the Iliad. Wolf's narrator is Cassandra, whose thoughts we hear at the moment just before her murder by Clytemnestra in Sparta. Wolf's narrator presents a feminist's view of the war, and of war in general. Cassandra's story is accompanied by four essays which Wolf delivered as the Frankfurter Poetik-Vorlesungen. The essays present Wolf's concerns as a writer and rewriter of this canonical story and show the genesis of the novel through Wolf's own readings and in a trip she took to Greece.

A number of comic series have re-told the legend of the Trojan War. The most inclusive may be Age of Bronze, a comprehensive retelling by writer/artist Eric Shanower that incorporates a broad spectrum of literary traditions and archaeological findings. Started in 1999, it is projected to number seven volumes.

Bob Dylan recorded a song entitled "Temporary Like Achilles" for his 1966 album "Blonde On Blonde". Led Zeppelin recorded a song entitled "Achilles Last Stand" for their 1976 album Presence.

Power metal band Blind Guardian composed a 14 minute song about the Iliad, "And Then There Was Silence", appearing on the 2002 album A Night at the Opera.

Heavy metal band Manowar composed a 28 minute medley, "Achilles, Agony and Ecstasy in Eight Parts", in their 1992 album, The Triumph of Steel. Other heavy metal bands inspired by the epos: Manilla Road "The Fall Of Iliam"; Stormwind "War Of Try"; Virgin Steele composed a rock opera in two parts called The Fall Of House Atreus; Jag Panzer "Achilles"; Arcane "Agamemnon"; Warlord "Achilles Revenge"; Tierra Santa "El Caballo De Troya".

An epic science fiction adaptation/tribute by acclaimed author Dan Simmons titled Ilium was released in 2003. The novel received a Locus Award for best science fiction novel of 2003.

A loose film adaptation of the Iliad, Troy, was released in 2004, starring Brad Pitt as Achilles, Orlando Bloom as Paris, Eric Bana as Hector, Sean Bean as Odysseus and Brian Cox as Agamemnon. It was directed by German-born Wolfgang Petersen. The movie only loosely resembles the Homeric version, with the supernatural elements of the story were deliberately expunged, except for one scene that includes Achilles' sea nymph mother, Thetis (although her supernatural nature is never specifically stated, and she is aged as though human). Though the film received mixed reviews, it was a commercial success, particularly in international sales. It grossed $133 million in the United States and $497 million worldwide, placing it in the 64th top-grossing movie of all time.[41]

S.M. Stirling's Island in the Sea of Time series contains numerous characters who are clearly the "original versions" of those appearing in the Iliad. Odysseus himself plays a major role in the third and last book, On the Oceans of Eternity. The twentieth-century characters are quite aware of this and make rather frequent reference to it. One, for example, comments that "a big horse ought to be present at the fall of Troy", and another uses the glory that the poem would have brought its protagonists to turn one of them against his master.

Alesana's "The Third Temptation of Paris" is based on the theft of Helen and the subsequent consequences.

English translations

George Chapman published his translation of the Iliad, in instalments, beginning in 1598, published in “fourteeners”, a long-line ballad metre that “has room for all of Homer’s figures of speech and plenty of new ones, as well as explanations in parentheses. At its best, as in Achilles’ rejection of the embassy in Iliad Nine; it has great rhetorical power”. [42] It quickly established itself as a classic in English poetry. In the preface to his own translation, Pope praises “the daring fiery spirit” of Chapman’s rendering, which is “something like what one might imagine Homer, himself, would have writ before he arrived at years of discretion”. John Keats praised Chapman in the sonnet On First Looking into Chapman's Homer (1816). John Ogilby’s mid-seventeenth-century translation is among the early annotated editions; Alexander Pope’s 1715 translation, in heroic couplet, is “The classic translation that was built on all the preceding versions”, [43] and, like Chapman’s, it is a major poetic work, in its own right. William Cowper’s Miltonic, blank verse 1791 edition is highly regarded for its greater fidelity to the Greek than either the Chapman or the Pope versions: “I have omitted nothing; I have invented nothing”, Cowper says in prefacing his translation.

In the lectures On Translating Homer (1861), Matthew Arnold addresses the matters of translation and interpretation in rendering the Iliad to English; commenting upon the versions contemporarily available in 1861, he identifies the four essential poetic qualities of Homer to which the translator must do justice:

[i] that he is eminently rapid; [ii] that he is eminently plain and direct, both in the evolution of his thought and in the expression of it, that is, both in his syntax and in his words; [iii] that he is eminently plain and direct in the substance of his thought, that is, in his matter and ideas; and, finally, [iv] that he is eminently noble.

After a discussion of the metres employed by previous translators, Arnold argues for a poetical dialect hexameter translation of the Iliad, like the original. “Labourious as this meter was, there were at least half a dozen attempts to translate the entire Iliad or Odyssey in hexameters; the last in 1945. Perhaps the most fluent of them was by J. Henry Dart [1862] in response to Arnold”. [44]

Translators and translations

In 1870, the US poet William Cullen Bryant published a blank verse version, that Van Wyck Brooks describes as “simple, faithful”. Moreover, since 1950, there have been several English translations. Richmond Lattimore’s version is “a free six-beat” line-for-line rendering that explicitly eschews “poetical dialect” for “the plain English of today”; it is literal, unlike older verse renderings. Robert Fitzgerald’s version strives to situate the Iliad in the musical forms of English poetry; his forceful version is freer, with shorter lines that increase the sense of swiftness and energy. In comparison, Lattimore’s rendering might seem dull and plodding, where Fitzgerald’s “voice . . . [is] sometimes a better reflection of the nuances and connotations in the original Greek than [is] Lattimore’s” voice.

Robert Fagles and Stanley Lombardo are bolder in adding dramatic significance to Homer’s conventional and formulaic language; generally, Fagles’s fidelity to the original is greater, while Lombardo employs a distinctly American, colloquial, “steet verse” idiom that has been criticised as out-of-tune with Homer’s original diction. Rodney Merrill’s accentual, dactylic hexameter more accurately reproduces the poem’s original Greek sound and sense “by following the Homeric line, in its shape as well as its meter” with greater fidelity than previous translations.

Herbert Jordan’s is a line-for-line blank verse translation that the poet Henry Taylor says “moves quickly and fluidly” and that Bruce Louden (The Iliad: Structure, Myth, and Meaning) says includes “the most vivid translation ever done of the ‘Catalogue of Ships.’”

Given the strictures of iambic pentameter, Jordan does not translate many of the original epithets and patronyms because the object of his figurative translation “is to capture the essence of Homer’s individual lines, not to render the Greek literally” (p.ix). “With this in mind, if we take, by way of example, the phrase ἄναχ ἀνδρῶν Ἀγαμέμνων, we find that rather than translating this stock epithet exactly the same way every time it appears (as indeed Lattimore does), Jordan either omits Agamemnon’s epithet, or translates [it] variously as ‘high king,’ ‘high-commander,’ ‘warrior-chief,’ ‘chief warrior,’ ‘chief Greek warrior,’ ‘lord,’ ‘supreme commander,’ ‘far-ruling,’ ‘the king,’ and even ‘Atrides.’ The same is [true] for all the other stock phrases in the poem. Stock expressions, such as ‘so he spoke’ (ὥς ἔφατο) are almost entirely omitted. Whole line repetitions in the Greek appear differently in English. . . . Jordan’s translation ‘Each man’s heart steeled to support his comrades’, at line 9, is eminently better to read than [is] Lattimore’s painfully literal ‘Stubbornly minded each in his heart to stand by the others.’ (Fagles comes out best with the graphic ‘Hearts ablaze to defend each other to the death.’) Jordan’s Iliad is a very easy, vivid read. . . . [I]t is perhaps the most readable of all the verse translations of the Iliad to date. Yet it should be stated that what we read in this translation is not a true reflection of Homer. A reader discovering the Iliad for the first time in Jordan’s translation would miss much of the oral tradition that the Iliad inherently reflects. . . . Those seeking a more literal translation should look elsewhere.”[45]

English translations: a partial list

(see the complete list in English translations of Homer)

- George Chapman, 1598 and 1615 — verse

- John Ogilby, 1660

- Thomas Hobbes, 1675 — verse: full text

- John Ozell, William Broome, and William Oldisworth, 1712

- Alexander Pope, 1713 — verse: full text

- James Macpherson, 1773

- William Cowper, 1791: full text

- Theodore Alois Buckley, 1851 — prose: full text

- Lord Derby, 1864 — verse: full text

- J. Henry Dart, 1862 — hexameter verse

- William Cullen Bryant, 1870 — verse

- Walter Leaf, Andrew Lang and Ernest Myers, 1873 — prose: full text

- Samuel Butler, 1898 — prose: full text (many typographic errors, confusing to read).

- A.T. Murray, 1924 — —prose with facing Greek text: full text of translation

- Alexander Falconer, 1933

- Sir William Marris, 1934 — verse

- W.H.D. Rouse, 1938 — prose

- William Benjamin Smith and Walter Miller, 1944 — verse, in dactylic hexameter

- E.V. Rieu, 1950 — prose

- Alston Chase and William G. Perry, 1950 — prose

- Richmond Lattimore, 1951 -verse: full text with interlinear Greek text

- Ennis Rees, 1963 — verse

- Robert Fitzgerald, 1974 — verse

- Martin Hammond, 1987 — prose

- Robert Fagles, 1990 — verse

- Stanley Lombardo, 1997 — verse

- Ian Johnston, 2002 — verse: full text

- Rodney Merrill, 2007 — verse, in dactylic hexameter

- Herbert Jordan, 2008 — verse

- John Jackson, 2008 — Parsed Interlinear: text:parts blocked out

Notes

- ^ Benét’s Reder’s Encyclopedia (1996) p.324

- ^ Benét’s Reder’s Encyclopedia (1996) pp.500–02

- ^ Vidal-Naquet, Pierre. Le monde d’Homère (The World of Homer), Perrin (2000), p.19

- ^ Rouse, W.H.D. The Iliad (1938) p.11

- ^ Hornblower, S., Spawforth, A. The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (1998). pp.357–74

- ^ Benét’s Reader’s Encyclopedia, Fourth Edition, (1996). p.324

- ^ Richardson, Nicholas, The Iliad: A Commentary, Cambridge university press, 1993, v.6, p.20-21.

- ^ a b Per Garner, From Homer to Tragedy New York (1990), p.179, books VI and XXII are the most-imitated and alluded by Greek poets.

- ^ Iliad IX 410–16

- ^ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951)

- ^ Rouse, W.H.D. The Iliad (1938) p.11

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 1.13.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 1.122.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 1.181–7.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 18.111–16.

- ^ Fate as presented in Homer's "The Iliad", Everything2

- ^ Iliad Study Guide, Brooklyn College

- ^ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 16.849–54.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 16.433–4.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 16.440–3.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 22.178–81.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 20.300–4.

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition (1994) p.173

- ^ Porter, John. The Iliad as Oral Formulaic Poetry (8 May 2006) University of Saskatchewan; accessed 26 November 2007.

- ^ Lord, Albert. The Singer of Tales Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press (1960) p.190

- ^ Lord, Albert. The Singer of Tales Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press (1960) p.195

- ^ Iliad, Book XVI, 130–54

- ^ Armstrong, James I. The Arming Motif in the Iliad. The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 79, No. 4. (1958), pp.337–54.

- ^ Toohey, Peter. Reading Epic: An Introduction to the Ancient Narrative. New Fetter Lane, London: Routledge, (1992).

- ^ Hornblower, S. and Spawforth, A. The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization pp.3, 352

- ^ Hornblower, S. and Spawforth, A. The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (1998) p.347

- ^ Iliad 3.45–50

- ^ Iliad 5.59–65

- ^ Keegan, John. A History of Warfare (1993) p.248

- ^ Iliad 6.6

- ^ Cahill, Tomas. Sailing the Wine Dark Sea: Why the Greeks Matter (2003)

- ^ Homer’s Iliad, Classical Technology Center.

- ^ Lefkowitz, Mary. Greek Gods, Human Lives: What We Can Learn From Myths (2003) New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press

- ^ Taplin, Oliver. “Bring Back the Gods”, The New York Times 14 December 2003.

- ^ Bruce B. Lawrence and Aisha Karim (2008). On Violence: A Reader. Duke University Press. p. 377. ISBN 978-0822337690.

- ^ IMDB. "All Time Worldwide Box Office Grosses", Box Office Mojo

- ^ The Oxford Guide to English Literature in Translation, p.351

- ^ The Oxford Guide to English Literature in Translation, p.352

- ^ The Oxford Guide to English Literature in Translation, p.354

- ^ Calum Maciver,Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2009.01.15

References

- Budimir, Milan (1940). On the Iliad and Its Poet.

- Mueller, Martin (1984). The Iliad. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-800027-2.

- Nagy, Gregory (1979). The Best of the Achaeans. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-2388-9.

- Powell, Barry B. (2004). Homer. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. 978-1-4051-5325-6.

- Seaford, Richard (1994). Reciprocity and Ritual. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815036-9.

- West, Martin (1997). The East Face of Helicon. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815221-3.

- Fox, Robin Lane (2008). Travelling Heroes: Greeks and their myths in the epic age of Homer. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-713-99980-8.

External links

- Iliad, online version of the work by Homer (English). Pope translation.

- Iliad in Ancient Greek: from the Perseus Project (PP), with the Murray and Butler translations and hyperlinks to mythological and grammatical commentary; via the Chicago Homer, with the Lattimore translation and markup indicating formulaic repetitions

- Links to translations freely available online are included in the list above.

- The Iliad: A Study Guide

- Classical images illustrating the Iliad. Repertory of outstanding painted vases, wall paintings and other ancient iconography of the War of Troy.

- Comments on background, plot, themes, authorship, and translation issues by 2008 translator Herbert Jordan.

- Homer: Iliad Books 1-12, & 13-24, ed. by Monro, 3rd Ed.: © Oxford Univ. Press 1902, parsed interlinear eBook for Palm Handheld

- The Iliad study guide, themes, quotes, teacher resources