Flowchart

A flowchart is a common type of diagram, that represents an algorithm or process, showing the steps as boxes of various kinds, and their order by connecting these with arrows. Flowcharts are used in analyzing, designing, documenting or managing a process or program in various fields.[1]

History

The first structured method for documenting process flow, the "flow process chart", was introduced by Frank Gilbreth to members of ASME in 1921 as the presentation “Process Charts—First Steps in Finding the One Best Way”. Gilbreth's tools quickly found their way into industrial engineering curricula. In the early 1930s, an industrial engineer, Allan H. Mogensen began training business people in the use of some of the tools of industrial engineering at his Work Simplification Conferences in Lake Placid, New York.

A 1944 graduate of Mogensen's class, Art Spinanger, took the tools back to Procter and Gamble where he developed their Deliberate Methods Change Program. Another 1944 graduate, Ben S. Graham, Director of Formcraft Engineering at Standard Register Corporation, adapted the flow process chart to information processing with his development of the multi-flow process chart to displays multiple documents and their relationships. In 1947, ASME adopted a symbol set derived from Gilbreth's original work as the ASME Standard for Process Charts by Mishad,Ramsan,Raiaan.

Douglas Hartree explains that Herman Goldstine and John von Neumann developed the flow chart (originally, diagram) to plan computer programs.[2] His contemporary account is endorsed by IBM engineers[3] and by Goldstine's personal recollections.[4] The original programming flow charts of Goldstine and von Neumann can be seen in their unpublished report, "Planning and coding of problems for an electronic computing instrument, Part II, Volume 1," 1947, which is reproduced in von Neumann's collected works.[5]

Flowcharts used to be a popular means for describing computer algorithms and are still used for this purpose.[6] Modern techniques such as UML activity diagrams can be considered to be extensions of the flowchart. However, their popularity decreased when, in the 1970s, interactive computer terminals and third-generation programming languages became the common tools of the trade, since algorithms can be expressed much more concisely and readably as source code in such a language. Often, pseudo-code is used, which uses the common idioms of such languages without strictly adhering to the details of a particular one.

Flowchart building blocks

Symbols

A typical flowchart from older Computer Science textbooks may have the following kinds of symbols:

- Start and end symbols

- Represented as circles, ovals or rounded rectangles, usually containing the word "Start" or "End", or another phrase signaling the start or end of a process, such as "submit enquiry" or "receive product".

- Arrows

- Showing what's called "flow of control" in computer science. An arrow coming from one symbol and ending at another symbol represents that control passes to the symbol the arrow points to.

- Processing steps

- Represented as rectangles. Examples: "Add 1 to X"; "replace identified part"; "save changes" or similar.

- Input/Output

- Represented as a parallelogram. Examples: Get X from the user; display X.

- Conditional or decision

- Represented as a diamond (rhombus). These typically contain a Yes/No question or True/False test. This symbol is unique in that it has two arrows coming out of it, usually from the bottom point and right point, one corresponding to Yes or True, and one corresponding to No or False. The arrows should always be labeled. More than two arrows can be used, but this is normally a clear indicator that a complex decision is being taken, in which case it may need to be broken-down further, or replaced with the "pre-defined process" symbol.

A number of other symbols that have less universal currency, such as:

- A Document represented as a rectangle with a wavy base;

- A Manual input represented by parallelogram, with the top irregularly sloping up from left to right. An example would be to signify data-entry from a form;

- A Manual operation represented by a trapezoid with the longest parallel side at the top, to represent an operation or adjustment to process that can only be made manually.

- A Data File represented by a cylinder.

Flowcharts may contain other symbols, such as connectors, usually represented as circles, to represent converging paths in the flowchart. Circles will have more than one arrow coming into them but only one going out. Some flowcharts may just have an arrow point to another arrow instead. These are useful to represent an iterative process (what in Computer Science is called a loop). A loop may, for example, consist of a connector where control first enters, processing steps, a conditional with one arrow exiting the loop, and one going back to the connector. Off-page connectors are often used to signify a connection to a (part of another) process held on another sheet or screen. It is important to remember to keep these connections logical in order. All processes should flow from top to bottom and left to right.

Examples

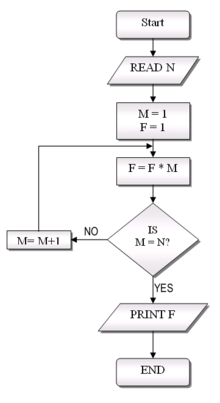

A flowchart for computing factorial N (N!) where N! = (1 * 2 * 3 * ... * N). This flowchart represents a "loop and a half" — a situation discussed in introductory programming textbooks that requires either a duplication of a component (to be both inside and outside the loop) or the component to be put inside a branch in the loop.

Types of flowcharts

There are many different types of flowcharts. On the one hand there are different types for different users, such as analysts, designers, engineers, managers, or programmers.[7] On the other hand those flowcharts can represent different types of objects. Sterneckert (2003) divides four more general types of flowcharts:[7]

- Document flowcharts, showing a document flow through system

- Data flowcharts, showing data flows in a system

- System flowcharts showing controls at a physical or resource level

- Program flowchart, showing the controls in a program within a system

However there are several of these classifications. For example Andrew Veronis (1978) named three basic types of flowcharts: the system flowchart, the general flowchart, and the detailed flowchart.[8] That same year Marilyn Bohl (1978) stated "in practice, two kinds of flowcharts are used in solution planning: system flowcharts and program flowcharts...".[9] More recently Mark A. Fryman (2001) stated that there are more differences. Decision flowcharts, logic flowcharts, systems flowcharts, product flowcharts, and process flowcharts are "just a few of the different types of flowcharts that are used in business and government.[10]

Software

Manual

Any vector-based drawing program can be used to create flowchart diagrams, but these will have no underlying data model to share data with databases or other programs such as project management systems or spreadsheets. Some tools offer special support for flowchart drawing, e.g., ConceptDraw, SmartDraw, Visio, OmniGraffle or the open source Dia (software).

Automatic

Many software packages exist that can create flowcharts automatically, either directly from source code, or from a flowchart description language. For example, Graph::Easy, a Perl package, takes a textual description of the graph, and uses the description to generate various output formats including HTML, ASCII or SVG.

Web-based

Recently, online flowchart solutions have become available, e.g., DrawAnywhere. It is easy to use and flexible but does not meet the power of off-line software like Visio or SmartDraw.

See also

- Activity diagram

- Augmented transition network

- Business process illustration

- Business Process Mapping

- Control flow diagram

- Control flow graph

- Data flow diagram

- Deployment flowchart

- Diagramming software

- Flow map

- Functional flow block diagram

- N2 Chart

- Petri nets

- Process architecture

- Pseudocode

- Recursive transition network

- Sankey diagram

- State diagram

- Warnier-Orr

- Unified Modeling Language (UML)

- structured flowchart, also called a Nassi-Shneiderman diagram

Notes

- ^ SEVOCAB: Software and Systems Engineering Vocabulary. Term: Flow chart. retrieved 31 July 2008.

- ^ Hartree, Douglas (1949). Calculating Instruments and Machines. The University of Illinois Press. p. 112.

- ^ Bashe, Charles (1986). IBM's Early Computers. The MIT Press. p. 327.

- ^ Goldstine, Herman (1972). The Computer from Pascal to Von Neumann. Princeton University Press. pp. 266–267. ISBN 0-691-08104-2.

- ^ Taub, Abraham (1963). John von Neumann Collected Works. Vol. 5. Macmillan. pp. 80–151.

- ^ Bohl, Rynn: "Tools for Structured and Object-Oriented Design", Prentice Hall, 2007.

- ^ a b Alan B. Sterneckert (2003)Critical Incident Management. p.126

- ^ Andrew Veronis (1978) Microprocessors: Design and Applications. Page 111

- ^ Marilyn Bohl (1978) A Guide for Programmers. Page 65.

- ^ Mark A. Fryman (2001) Quality and Process Improvement. Page 169.

Further reading

- ISO (1985). Information processing -- Documentation symbols and conventions for data, program and system flowcharts, program network charts and system resources charts. International Organization for Standardization. ISO 5807:1985.

External links

- Flowcharting Techniques An IBM manual from 1969 (5MB PDF format)

- Introduction to Programming in C++ flowchart and pseudocode (PDF)

- Advanced Flowchart - Why and how to create advanced flowchart