Tagalog language

- Tagalog redirects here. For the original users of the language, see Tagalog people. For the script that was formerly used for this language, see Baybayin.

| Tagalog | |

|---|---|

| Wikang Tagalog ᜆᜄᜎᜓᜄ[1] | |

| Native to | and a small number of the populations of |

| Region | Central and South Luzon |

Native speakers | First language (in the Philippines): 49 million[2][3]

|

| Latin (Tagalog or Filipino variant); Historically written in Alibata (ᜀᜎᜒᜊᜆ) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Commission on the Filipino Language |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | tl |

| ISO 639-2 | tgl |

| ISO 639-3 | tgl – inclusive codeIndividual code: tgl – Tagalog |

The locations where Tagalog is spoken. Red represents countries where it is an official language (as Filipino), maroon represents where it is recognized as a minority language, pink represents other places where it is spoken significantly. | |

Tagalog is an Austronesian language spoken in the Philippines by about 22 million people.[2] It is related to Austronesian languages such as Chamorro (of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands), Indonesian, Malay, Javanese and Paiwan (of Taiwan), Cham (of Vietnam and Cambodia), and Tetum (of East Timor). It is the first language of the Philippines' Region IV (CALABARZON and MIMAROPA) and is the basis[4] for the national and the official language of the Philippines, Filipino.[5]

History

The word Tagalog derived from tagailog, from tagá- meaning "native of" and ílog meaning "river." Thus, it means "river dweller." Very little is known about the history of the language. However, according to linguists such as Dr. David Zorc and Dr. Robert Blust, the Tagalogs originated, along with their Central Philippine cousins, from Northeastern Mindanao or Eastern Visayas.[6][7]

The first written record of Tagalog is in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, written in the year 900 and uses fragments of the language along with Sanskrit, Malay, and Javanese. Meanwhile, the first known book to be written in Tagalog is the Doctrina Cristiana (Christian Doctrine) of 1593. It was written in Spanish and two versions of Tagalog; one written in the Baybayin script and the other in the Latin alphabet. Throughout the 333 years of Spanish occupation, there were grammar and dictionaries written by Spanish clergymen such as Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala by Pedro de San Buenaventura (Pila, Laguna, 1613), Vocabulario de la lengua tagala (1835) and Arte de la lengua tagala y manual tagalog para la administración de los Santos Sacramentos (1850). Poet Francisco Baltazar (1788–1862) is regarded as the foremost Tagalog writer. His most famous work is the early 19th-century Florante at Laura.

Tagalog and Filipino

In 1937, Tagalog was selected as the basis of the national language of the Philippines by the National Language Institute. In 1939, Manuel L. Quezon named the national language "Wikang Pambansâ" ("National Language").[8] Twenty years later, in 1959, it was renamed by the Secretary of Education, Jose Romero, as Pilipino to give it a national rather than ethnic label and connotation. The changing of the name did not, however, result in acceptance among non-Tagalogs, especially Cebuanos who had not accepted the selection.[9].

In 1971, the language issue was revived once more, and a compromise solution was worked out—a "universalist" approach to the national language, to be called Filipino rather than Pilipino. When a new constitution was drawn up in 1987, it named Filipino as the national language.[9] The constitution specified that as the Filipino language evolves, it shall be further developed and enriched on the basis of existing Philippine and other languages.

Classification

Tagalog is a Central Philippine language within the Austronesian language family. Being Malayo-Polynesian, it is related to other Austronesian languages such as Javanese, Indonesian, Malay,Chamorro (of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands), Tetum (of East Timor), and Paiwan (of Taiwan). It is closely related to the languages spoken in the Bicol and Visayas regions such as Bikol and the Visayan group including Hiligaynon, Waray-Waray, and Cebuano.

Languages that have made significant contributions to Tagalog are Spanish, English, Hindi, Arabic, Sanskrit, Old Malay, Chinese, Javanese, Japanese, and Tamil.

Dialects

At present, no comprehensive dialectology has been done in the Tagalog-speaking regions, though there have been descriptions in the form of dictionaries and grammars on various Tagalog dialects. Ethnologue lists Lubang, Manila, Marinduque, Bataan, Batangas, Bulacan, Tanay-Paete, and Tayabas as dialects of Tagalog. However, there appear to be four main dialects of which the aforementioned are a part; Northern (exemplified by the Bulacan dialect), Central (including Manila), Southern (exemplified by Batangas), and Marinduque.

Some example of dialectal differences are:

- Many Tagalog dialects, particularly those in the south, preserve the glottal stop found after consonants and before vowels. This has been lost in standard Tagalog. For example standard Tagalog ngayon (now, today), sinigang (broth stew), gabi (night), matamis (sweet), are pronounced and written ngay-on, sinig-ang, gab-i, and matam-is in other dialects.

- In Teresian-Morong Tagalog, [ɾ] is usually preferred over [d]. For example, bundók, dagat, dingdíng, and isdâ become bunrok, ragat, ringring, and isra, as well as their expression seen in some signages like "sandok sa dingding" was changed to "sanrok sa ringring".

- In many southern dialects, the progressive aspect prefix of -um- verbs is na-. For example, standard Tagalog kumakain (eating) is nákáin in Quezon and Batangas Tagalog. This is the butt of some jokes by other Tagalog speakers since a phrase such as nakain ka ba ng pating is interpreted as "did a shark eat you?" by those from Manila but in reality means "do you eat shark?" to those in the south.

- Some dialects have interjections which are a considered a trademark of their region. For example, the interjection ala e! usually identifies someone from Batangas as does hane?! in Rizal and Quezon provinces.

Perhaps the most divergent Tagalog dialects are those spoken in Marinduque. Linguist Rosa Soberano identifies two dialects, western and eastern with the former being closer to the Tagalog dialects spoken in the provinces of Batangas and Quezon.

One example are the verb conjugation paradigms. While some of the affixes are different, Marinduque also preserves the imperative affixes, also found in Visayan and Bikol languages, that have mostly disappeared from most Tagalog dialects by the early 20th century; they have since merged with the infinitive.

| Manileño Tagalog | English |

|---|---|

| Susulat sina Maria at Fulgencia kay Juan. | "Maria and Fulgencia will write to Juan." |

| Mag-aaral siya sa Maynila. | "He will study in Manila." |

| Magluto ka! | "Cook!" |

| Kainin mo iyan. | "Eat that." |

| Tinatawag nga tayo ni Tatay. | "Father is calling the two of us." |

| Tutulungan ba kayó ni Hilario? | "Will Hilario help you (pl.)?" |

Northern and Central Dialects have influences from Kapampangan while those near the Bicol have influences from Daet Bikol.

Features

Geographic distribution

The Tagalog homeland, or Katagalugan, covers roughly much of the central to southern parts of the island of Luzon - particularly in Aurora, Bataan, Batangas, Bulacan, Camarines Norte, Cavite, Laguna, Metro Manila, Nueva Ecija, Quezon, Rizal, and large parts of Zambales. Tagalog is also spoken natively by inhabitants living on the islands, Marinduque, Mindoro, and large areas of Palawan. It is spoken by approximately 64.3 million Filipinos, 96.4% of the household population.[10] 21.5 million, or 28.15% of the total Philippine population,[11] speak it as a native language.

Tagalog speakers are found in other parts of the Philippines as well as throughout the world, though its use is usually limited to communication between Filipino ethnic groups. In[update] 2003, the US Census bureau reported (based on data from the 2000 census) that it was the fourth most-spoken language in the United States, with over 1.2 million speakers[12]. In Canada it is spoken by 235,615 [13][failed verification].

Official status

Tagalog was declared the official language by the first constitution in the Philippines, the Constitution of Biak-na-Bato in 1897.[14]

In 1935, the Philippine constitution designated English and Spanish as official languages, but mandated the development and adoption of a common national language based on one of the existing native languages.[15] After study and deliberation, the National Language Institute, a committee composed of seven members who represented various regions in the Philippines, chose Tagalog as the basis for the evolution and adoption of the national language of the Philippines.[9][16] President Manuel L. Quezon then, on December 30, 1937, proclaimed the selection of the Tagalog language to be used as the basis for the evolution and adoption of the national language of the Philippines.[16] In 1939 President Quezon renamed the proposed Tagalog-based national language as wikang pambansâ (national language).[9] In 1939, the language was further renamed as "Pilipino".[9]

The 1973 constitution designated the Tagalog-based "Pilipino", along with English, as an official language and mandated the development and formal adoption of a common national language to be known as Filipino.[17] The 1987 constitution designated Filipino as the national language, mandating that as it evolves, it shall be further developed and enriched on the basis of existing Philippine and other languages.[5]

As Filipino, Tagalog has been taught in schools throughout the Philippines. It is the only one out of over 170 Philippine languages that is officially used in schools and businesses, (info from culturegrams)[citation needed] though Article XIV, Section 7 of the 1987 Constitution of the Philippines does specify, in part:

Subject to provisions of law and as the Congress may deem appropriate, the Government shall take steps to initiate and sustain the use of Filipino as a medium of official communication and as language of instruction in the educational system.[5]

The regional languages are the auxiliary official languages in the regions and shall serve as auxiliary media of instruction therein.[5]

Other Philippine languages have influenced Filipino, primarily through migration from the provinces to Metro Manila of speakers of those other languages.

Besides the Philippines, the language enjoys relative minority status in Canada, the United Kingdom, and also Hong Kong, where street signs commonly display the language. In the United States, the language is used in censuses and elections.[18]

Code-switching

Taglish and Englog are portmanteaus given to a mix of English and Tagalog. The amount of English vs.Tagalog varies from the occasional use of English loan words to outright code-switching where the language changes in mid-sentence. Such code-switching is prevalent throughout the Philippines and in various of the languages of the Philippines other than Tagalog.

- Nasirà ang computer ko kahapon!

- "My computer broke yesterday!"

- Huwág kang maninigarilyo, because it is harmful to your health.

- "Don't smoke cigarettes, ..."

Code switching also entails the use of foreign words that are Filipinized by reforming them using Filipino rules, such as verb conjugations. Users typically use Filipino or English words, whichever comes to mind first or whichever is easier to use.

- Magshoshopping kami sa mall. Sino ba ang magdadrive sa shoppingan?

- "We will go shopping at the mall. Who will drive to the shopping center anyway?"

Although it is generally looked down upon, code-switching is prevalent in all levels of society; however, city-dwellers, the highly educated, and people born around and after World War II are more likely to do it. Politicians as highly placed as President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo have code-switched in interviews.

The practice is common in television, radio, and print media as well. Advertisements from companies like Wells Fargo, Wal-Mart, Albertsons, McDonald's, and Western Union have contained Taglish.

The Chinese and the non-Tagalog communities in the Philippines also frequently code-switch their language, be it Cebuano or Min Nan Chinese, with Taglish.

Phonology

Tagalog has 35 phonemes: 22 of them are consonants, 5 are vowels, and 8 are dipthongs.[1][failed verification] Syllable structure is relatively simple. Each syllable contains at least a consonant and a vowel,[19], and begins in at most one consonant, except for borrowed words such as trak which means "truck", or tsokolate meaning "chocolate".

Vowels

Before appearing in the coastal region of Manila, Tagalog had three vowel phonemes: /a/, /i/, and /u/. This was later expanded to five vowels with the introduction of Kapampangan and Spanish words.

They are:

- /a/ an open central unrounded vowel similar to English "father"; in the middle of a word, a mid central unrounded vowel similar to English "cup"

- /ɛ/ an open-mid front unrounded vowel similar to English "bed"

- /i/ a close front unrounded vowel similar to English "machine"

- /o/ a close-mid back rounded vowel similar to English "forty"

- /u/ a close back unrounded vowel similar to English "flute"

There are four main diphthongs; /ai/, /ei/, /oi/, /ui/, /au/, /eu/, /iu/, and /ou/.[19][1]

Consonants

Below is a chart of Tagalog consonants. All the stops are unaspirated. The velar nasal occurs in all positions including at the beginning of a word.

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Alveolo-palatal | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ʔ | |||||

| Fricative | s | ɕ | x (kx) | h | ||||||||

| Affricate | ts | tɕ | dʑ | |||||||||

| Tap | ɾ | |||||||||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||||||||

Stress

Stress is phonemic in Tagalog. Primary stress occurs on either the last or the next-to-the-last (penultimate) syllable of a word. Vowel lengthening accompanies primary or secondary stress except when stress occurs at the end of a word. Stress on words is highly important, since it differentiates words with the same spellings, but with different meanings, e.g. tayo(to stand) and tayo(us; we)

Sounds

Vowels

- /a/ is raised slightly to [ɐ] in unstressed positions and also occasionally in stressed positions (inang bayan [inˈɐŋ ˈbɐjən])

- Unstressed /i/ is usually pronounced [ɪ] as in English "bit"

- At the final syllable, /i/ can be pronounced [i ~ e ~ ɛ], as [e ~ ɛ] is an allophone of [ɪ ~ i] in final syllables.

- Unstressed /ɛ/ and /o/ can sometimes be pronounced [i ~ ɪ ~ e] and [u ~ ʊ ~ ɔ], except in final syllables. [o~ ʊ ~ ɔ] and [u ~ ʊ] were also former allophones.

- Unstressed /u/ is usually pronounced [ʊ] as in English "book"

- The diphthong /aɪ/ and the sequence /aʔi/ have a tendency to become [eɪ ~ ɛː].

- The diphthong /aʊ/ and the sequence /aʔu/ have a tendency to become [oʊ ~ ɔː].

- /e/ or /i/ before s-consonant clusters have a tendency to become silent.

Consonants

- /k/ between vowels has a tendency to become [x] as in Spanish "José" or Arabic "Khadijah", whereas in the initial position it has a tendency to become [kx].

- Intervocalic /ɡ/ and /k/ tend to become [ɰ] (see preceding), as in Arabic "ghair".

- /ɾ/ and /d/ are sometimes interchangeable as /ɾ/ and /d/ were once allophones in Tagalog.

- A glottal stop that occurs at the end of a word is often omitted when it is in the middle of a sentence, especially in the Metro Manila area. The vowel it follows is then usually lengthened. However, it is preserved in many other dialects.

- /o/ tends to become [ɔ] in stressed positions.

- /nij/, /sij/, /tij/, and /dij/ may be pronounced [nj ~ nij], [sj ~ sij], [tj ~ tij] and [dj ~ dij], respectively, especially in everyday vernacular.

- /ts/ may be pronounced [ts], especially in but not limited to rural areas.

- /n/ and /ŋ/ can be in free variation in the end of the word.

- /ɾ/ can be pronounced [r].

- /b/ can be pronounced [ɓ].

Historical changes

Tagalog differs from its Central Philippine counterparts with its treatment of the Proto-Philippine schwa vowel *ə. In Bikol & Visayan, this sound merged with /u/ and [o]. In Tagalog, it has merged with /i/. For example, Proto-Philippine *dəkət (adhere, stick) is Tagalog dikít and Visayan & Bikol dukot.

Proto-Philippine *r, *j, and *z merged with /d/ but is /l/ between vowels. Proto-Philippine *nɡajan (name) and *hajək (kiss) became Tagalog ngalan and halík.

Proto-Philippine *R merged with /ɡ/. *tubiR (water) and *zuRuʔ (blood) became Tagalog tubig and dugô.

Grammar

Writing system

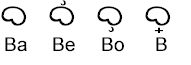

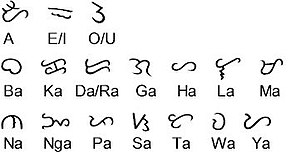

Baybayin

Tagalog was written in an abugida, or alphasyllabary, called Baybayin prior to the Spanish colonial period in the Philippines, in the 16th century. This particular writing system was composed of symbols representing three vowels and 14 consonants. Belonging to the Brahmic family of scripts, it shares similarities with the Old Kawi script of Java and is believed to be descended from the script used by the Bugis in Sulawesi.

Although it enjoyed a relatively high level of literacy, Baybayin gradually fell into disuse in favor of the Latin alphabet taught by the Spaniards during their rule.

There has been confusion of how to use Baybayin, which is actually an abugida, or an alphasyllabary, rather than an alphabet. Not every letter in the Latin alphabet is represented with one of those in the Baybayin alphasyllabary. Rather than letters being put together to make sounds as in Western languages, Baybayin uses symbols to represent syllables.

A "kudlit" resembling an apostrophe is used above or below a symbol to change the vowel sound after its consonant. If the kudlit is used above, the vowel is an "E" or "I" sound. If the kudlit is used below, the vowel is an "O" or "U" sound. A special kudlit was later added by Spanish missionaries in which a cross placed below the symbol to get rid of the vowel sound all together, leaving a consonant. Previously, the final vowel was just left out, leaving the reader to use context to determine the final vowels.

Example:

Baybayin is encoded in Unicode version 3.2 in the range 1700-171F under the name "Tagalog".

Latin alphabet

Until the first half of the 20th century, Tagalog was widely written in a variety of ways based on Spanish orthography. When the national language was based on Tagalog, grammarian Lope K. Santos introduced a new alphabet consisting of 20 letters called ABAKADA in school grammar books called balarilà:

In 1987 the department of Education, Culture and Sports issued a memo stating that the Philippine alphabet had changed from the Pilipino-Tagalog Abakada version to a new 28-letter alphabet:

to make room for loans, especially family names from Spanish and English.[25]

ng and mga

- See also: ng (digraph)

The genitive marker ng and the plural marker mga are abbreviations that are pronounced nang [naŋ] and mangá [mɐˈŋa]. Ng, in most cases, roughly translates to "of" (ex. Siya ay kapatid ng nanay ko. She is the sibling of my mother) while nang usually means "when" or can describe how something is done or to what extent, among other uses. Mga (pronounced as "muh-NGA") denotes plurality as adding an s, es, or ies does in English (ex. Iyan ang mga damit ko. (Those are my clothes)).

- Nang si Hudas ay madulas. - When Judas slipped.

- Gumising nang maaga siya. - He woke up early.

- Gumaling nang todo si Juan dahil nagensayo siya. - Juan improved greatly because he practiced.

In the first example, nang is used in lieu of the word noong (when; Noong si Hudas ay madulas). In the second, nang describes that the person woke up (gumising) early (maaga); gumising nang maaga. In the third, nang described up to what extent that Juan improved (gumaling), which is "greatly" (nang todo). In the latter two examples, the ligature na and its variants -ng and -g may also be used (Gumising na maaga/Maagang gumising; Gumaling na todo/Todong gumaling).

The longer nang may also have other uses, such as a ligature that joins a repeated word:

- Sumalita nang sumalita sila. - They kept talking and talking.

Vocabulary and borrowed words

Spanish is the language that has bequeathed the most loan words to Tagalog. According to linguists, Spanish (5,000) has even surpassed Malayo-Indonesian (3,500) in terms of loan words borrowed. About 40% of everyday (informal) Tagalog conversation is practically made up of Spanish loanwords.[citation needed]

Tagalog vocabulary is composed mostly of words of Austronesian origin with borrowings from Japanese, Tamil, Sanskrit, Min Nan Chinese (also known as Hokkien), Javanese, Malay, Arabic, Persian, Kapampangan, languages spoken on Luzon, and others, especially other Austronesian languages.

Due to trade with Mexico via the Manila galleon from the 16th to the 19th centuries, many words from Nahuatl, a language spoken by Native Americans in Mexico, were introduced to Tagalog.

English has borrowed some words from Tagalog, such as abaca, adobo, aggrupation, barong, balisong, boondocks, jeepney, Manila hemp, pancit, ylang ylang, and yaya, although the vast majority of these borrowed words are only used in the Philippines as part of the vocabularies of Philippine English.[citation needed]

Tagalog words of foreign origin chart

For the Min Nan Chinese borrowings, the parentheses indicate the equivalent in standard Chinese.

| Tagalog | meaning | language of origin | original spelling |

|---|---|---|---|

| kumustá | how are you? (general greeting) | Spanish | cómo está |

| kabayo | horse | Spanish | caballo |

| silya | chair | Spanish | silla |

| kotse | car | Spanish | coche |

| reló | wristwatch | Spanish | reloj |

| litrato | picture | Spanish | retrato |

| tsismis (chis-mis) | gossip | Spanish | chismes |

| Ingglés | English | Spanish | inglés |

| tsinelas (si-ne-las) | slippers | Spanish | chinelas |

| karne | meat | Spanish | carne |

| sapatos | shoes | Spanish | zapatos |

| arina/harina | flour | Spanish | harina |

| bisikleta | bicycle | Spanish | bicicleta |

| baryo | village | Spanish | barrio |

| swerte | luck | Spanish | suerte |

| piyesta/pista | feast | Spanish | fiesta |

| garáhe | garage | Spanish | garaje |

| ahente | agent/salesman | Spanish | agente |

| ensaymada (en-se-ma-da) | a kind of pastry | Catalan | ensaïmada |

| kamote | sweet potato | Nahuatl | camotli |

| sayote (sa-yo-te) | chayote, choko | Nahuatl | hitzayotli |

| sili | chili pepper | Nahuatl | chili |

| tsokolate (cho-co-la-te) | chocolate | Nahuatl | cocolatl |

| tiangge | market | Nahuatl | tianquiztli |

| sapote | chico (fruit) | Nahuatl | tzapotl |

| nars | nurse | English | nurse |

| bolpen | ballpoint pen | English | ballpen |

| bwisit | annoyance, expletive | English | bullshit |

| pulis | police | English | police |

| suspek | suspect | English | suspect |

| tráysikel | tricycle | English | tricycle |

| lumpia (/lum·pyâ/) | spring roll | Min Nan Chinese | 潤餅 (春捲) |

| siopao (/syó·paw/) | steamed buns | Min Nan Chinese | 燒包 (肉包) |

| pansít (/pan·set/) | noodles | Min Nan Chinese | 扁食 (麵) |

| susì (su-se) | key | Min Nan Chinese | 鎖匙 |

| kuya (see Philippine kinship) | older brother | Min Nan Chinese | 哥亞 (哥仔) |

| ate (/ah·te/) (see Philippine kinship) | older sister | Min Nan Chinese | 亞姐 (阿姐) |

| bakyâ | wooden shoes | Min Nan Chinese | 木履 |

| hikaw | earrings | Min Nan Chinese | 耳鈎 (耳環) |

| kanan | right | Malay | kanan |

| tulong | help | Malay | tolong |

| sakit | sick, pain | Malay | sakit |

| pulo | island | Malay | pulau |

| anak | child,son&daughter | Malay | anak |

| pinto | door | Malay | pintu |

| tanghalì | afternoon | Malay | tengah hari |

| dalamhatì | grief | Malay | dalam + hati |

| luwalhatì | glory | Malay | luar + hati |

| duryán | durian | Malay | durian |

| rambután | rambutan | Malay | rambutan |

| batík | spot | Malay | batik |

| saráp | delicious | Malay | sedap |

| asa | hope | Sanskrit | आशा |

| salitâ | speak | Sanskrit | चरितँ (cerita) |

| balità | news | Sanskrit | वार्ता (berita) |

| karma | karma | Sanskrit | कर्म |

| alak | liquor | Persian | عرق (arak) |

| manggá | mango | Tamil | மாங்காய்(mángáy) |

| bagay | thing | Tamil | வகை(vagai) |

| hukóm | judge | Arabic | حكم |

| salamat | thanks | Arabic | سلامة |

| bakit | why | Kapampangan | obakit |

| akyát | climb/step up | Kapampangan | ukyát/mukyat |

| at | and | Kapampangan | at |

| bundók | mountain | Kapampangan | bunduk |

| huwág | don't | pangasinan | ag |

| aso | dog | South Cordilleran or Ilocano | aso |

| tayo | we (inc.) | South Cordilleran or Ilocano | tayo |

| ito,nito | it. | pangasinan | to |

Austronesian comparison chart

Below is a chart of Tagalog and twenty other Austronesian languages comparing thirteen words; the first thirteen languages are spoken in the Philippines and the other seven are spoken in Indonesia, East Timor, New Zealand, Hawaii, and Madagascar.

| English | one | two | three | four | person | house | dog | coconut | day | new | we | what | fire |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tagalog | isa | dalawa | tatlo | apat | tao | bahay | aso | niyog | araw | bago | tayo | ano | apoy |

| Bikol | saro | duwa | tulo | apat | tawo | harong | ayam | niyog | aldaw | ba-go | kita | ano | kalayo |

| Cebuano | usa | duha | tulo | upat | tawo | balay | iro | lubi | adlaw | bag-o | kita | unsa | kalayo |

| Waray | usa | duha | tulo | upat | tawo | balay | ayam | lubi | adlaw | bag-o | kita | ano | kalayo |

| Tausug | hambuuk | duwa | tu | upat | tau | bay | iru' | niyug | adlaw | ba-gu | kitaniyu | unu | kayu |

| Kinaray-a | sara | darwa | tatlo | apat | taho | balay | ayam | niyog | adlaw | bag-o | kita, taten | ano | kalayo |

| Maranao | isa | dowa | t'lo | phat | taw | walay | aso | neyog | gawi'e | bago | tano | tonaa | apoy |

| Kapampangan | metung | adwa | atlu | apat | tau | bale | asu | ngungut | aldo | bayu | ikatamu | nanu | api |

| Pangasinan | sakey | dua, duara | talo, talora | apat, apatira | too | abong | aso | niyog | ageo | balo | sikatayo | anto | pool |

| Ilokano | maysa | dua | tallo | uppat | tao | balay | aso | niog | aldaw | baro | datayo | ania | apoy |

| Ivatan | asa | dadowa | tatdo | apat | tao | vahay | chito | niyoy | araw | va-yo | yaten | ango | apoy |

| Ibanag | tadday | dua | tallu | appa' | tolay | balay | kitu | niuk | aggaw | bagu | sittam | anni | afi |

| Gaddang | antet | addwa | tallo | appat | tolay | balay | atu | ayog | aw | bawu | ikkanetam | sanenay | afuy |

| Tboli | sotu | lewu | tlu | fat | tau | gunu | ohu | lefo | kdaw | lomi | tekuy | tedu | ofih |

| Indonesian | satu | dua | tiga | empat | orang | rumah/balai | anjing | kelapa/nyiur | hari | baru | kita | apa/anu | api |

| Buginese | sedi | dua | tellu | eppa | tau | bola | asu | kaluku | esso | baru | idi | aga | api |

| Bataknese | sada | dua | tolu | opat | halak | jabu | biang | harambiri | ari | baru | hita | aha | api |

| Tetum | ida | rua | tolu | haat | ema | uma | asu | nuu | loron | foun | ita | saida | ahi |

| Maori | tahi | rua | toru | wha | koiwi | whare | kuri | kokonati | ra | hou | taua | aha | ahi |

| Hawaiian | kahi | lua | kolu | hā | kanaka | hale | 'īlio | niu | ao | hou | kākou | aha | ahi |

| Malagasy | isa | roa | telo | efatra | olona | trano | alika | voanio | andro | vaovao | isika | inona | afo |

Contribution to other languages

Tagalog itself has contributed a few words into English.

- boondocks: meaning "rural" or "back country," was imported by American soldiers stationed in the Philippines following the Spanish American War as a mispronounced version of the Tagalog bundok, which means "mountain."

- cogon: a type of grass, used for thatching. This word came from the Tagalog word kugon (a species of tall grass).

- ylang-ylang: a type of flower known for its fragrance.

- Abaca: a type of hemp fiber made from a plant in the banana family, from abaká.

- Manila hemp: a light brown cardboard material used for folders and paper usually made from abaca hemp.

- Capiz: also known as window oyster, is used to make windows.

Yo-yo is reportedly a Tagalog word; however, no such word exists in Tagalog.

Tagalog has contributed several words to Philippine Spanish, like barangay (from balan͠gay, meaning barrio), the abacá, cogon, palay, etc.

Religious literature

Religious Literature remains to be one of the most dynamic contributors to Tagalog literature. In 1970, the Philippine Bible Society translated the Bible into Tagalog, the first full translation to any of the Philippine languages. Even before the Second Vatican Council, devotional materials in Tagalog had been circulating. At present, there are three circulating Tagalog translations of the Holy Bible—the Magandang Balita Biblia (a parallel translation of the Good News Bible), which is the ecumenical version; the Ang Biblia, which is a more Protestant version published in 1909; and the Bagong Sinlibutang Salin ng Banal na Kasulatan, one of about sixty parallel translations of the New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures published by Jehovah's Witnesses. The latter was released in the year 2000. Jehovah's Witnesses previously published a hybrid translation: Ang Biblia was used for the Old Testament, while the Bagong Sinlibutang Salin was used for the New Testament.

When the Second Vatican Council, (specifically the Sacrosanctum Concilium) permitted the universal prayers to be translated into vernacular languages, the Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines was one of the first to translate the Roman Missal into Tagalog. In fact, the Roman Missal in Tagalog was published as early as 1982, while not published in English until 1985.

Jehovah's Witnesses were printing Tagalog literature at least as early as 1941[26] and The Watchtower (the primary magazine of Jehovah's Witnesses) has been published in Tagalog since at least the 1960s. New releases are now regularly released simultaneously in a number of languages, including Tagalog. The official website of Jehovah's Witnesses also has some publications available online in Tagalog. [1]

Tagalog is quite a stable language, and very few revisions have been made to Catholic Bible translations. Also, as Protestantism in the Philippines is relatively young, liturgical prayers tend to be more ecumenical.

Examples

The Lord's Prayer (Ama Namin)

- Ama namin, sumasalangit Ka,

- Sambahin ang ngalan Mo.

- Mapasaamin ang kaharian Mo.

- Sundin ang loob Mo

- Dito sa lupa, para nang sa langit.

- Bigyan Mo kami ngayon ng aming kakanin sa araw araw.

- At patawarin Mo kami sa aming mga sala,

- Para nang pagpapatawad namin

- Sa mga nagkakasala sa amin.

- At huwag Mo kaming ipahintulot sa tukso,

- At iadya Mo kami sa lahat ng masama.

- Sapagkat Iyo ang kaharian, at kapangyarihan,

- At ang kadakilaan, magpakailanman.

- Amen.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Isinilang na malaya at pantay-pantay sa karangalan at mga karapatan ang lahat ng tao. Pinagkalooban sila ng katwiran at budhi at dapat magpalagayan ang isa't isa sa diwa ng pagkakapatiran.

(Every person is born free and equal with honor and rights. They are given reason and conscience and they must always trust each other for the spirit of brotherhood.)

Numbers

| Cardinal | Ordinal | |

| 1 | isá / uno | una |

| 2 | dalawá / dos | pangalawá / ikalawa |

| 3 | tatló / tres | pangatló / ikatlo |

| 4 | apat/cuatro | pang-apat / ika-apat |

| 5 | limá | panlimá / ikalima |

| 6 | anim | pang-anim / ika-anim |

| 7 | pitó | pampitó / ikapito |

| 8 | waló | pangwaló / ikawalo |

| 9 | siyám | pansiyám / ikasiyam |

| 10 | sampû | pansampû / ikasampu |

| 11 | labíng-isá / onse (Spanish numbers are commonly used above 10) | panlabíng-isá / pang-onse / ikalabing-isa |

| 12 | labindalawá / dose | panlabindalawá / pandose / ikalabindalawa |

| 20 | dalawampu / bente | pandalawampu/ pambente / ikadalawampu |

| 50 | limampu / singkwenta | |

| 100 | (i)sán(g)daán / syento | pan(g)-(i)sán(g)daán / pansyento / ika-(i)san(g)-daan |

| 200 | dalawáng daán / dos syentos | pandalawang daan / ikadalawang-daan |

| 400 | apat na raán / kwatro syentos | pang-apat na raán/ ika-apat na raán |

| 600 | anim na raán / saís syentos | |

| 1,000 | isáng libo (sanlibo) / mil | |

| 2,000 | dalawáng libo / dos mil | |

| 10,000 | (i)san(g)laksa / sampung libo / dyes mil | |

| 100,000 | (i)sangyuta / (i)sán(g)daáng libo / syento mil | |

| 1,000,000 | isáng milyón | |

| 2,000,000 | dalawáng milyón | |

| 10,000,000 | sampung milyón | |

| 100,000,000 | (i)sán(g)daáng milyon |

Common phrases

- Filipino: Pilipino [ˌpiːliˈpiːno]

- English: Ingglés [ʔɪŋˈɡlɛs]

- Tagalog: Tagalog [tɐˈɡaːloɡ]

- What is your name?: Anó ang pangalan ninyo? (plural) [ɐˈno aŋ pɐˈŋaːlan nɪnˈjo], Anó ang pangalan mo?(singular) [ɐˈno aŋ pɐˈŋaːlan mo]

- How are you?: kumustá [kʊmʊsˈta]

- Good morning!: Magandáng umaga! [mɐɡɐnˈdaŋ uˈmaːɡa]

- Good noontime! (from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m.): Magandáng tanghali! [mɐɡɐnˈdaŋ taŋˈhaːlɛ]

- Good afternoon! (from 1 p.m. to 6:00 p.m.): Magandáng hapon! [mɐɡɐnˈdaŋ ˈhaːpon]

- Good evening!: Magandáng gabí! [mɐɡɐnˈdaŋ ɡɐˈbɛ]

- Good-bye: paálam [pɐˈʔaːlam] (literal - "with your blessing")

- Please: Depending on the nature of the verb, either pakí- [pɐˈki] or makí- [mɐˈki] is attached as a prefix to a verb. ngâ [ŋaʔ] is optionally added after the verb to increase politeness.

- Thank you: salamat [sɐˈlaːmat]

- That one: iyan [ʔiˈjan]

- How much?: magkano? [mɐɡˈkaːno]

- Yes: oo [ˈoːʔo]

- No: hindî [hɪnˈdɛʔ]

- Sorry: pasensya pô (literally - "patience") or paumanhin po [pɐˈsɛːnʃa poʔ] patawad po [pɐtaːwad poʔ] (literally - "forgiveness")

- Because: kasí [kɐˈsɛ]

- Hurry!: Dalí! [dɐˈli], Bilís! [bɪˈlis]

- Again: mulí [muˈli] , ulít [ʊˈlɛt]

- I don't understand: Hindî ko maintindihan [hɪnˈdiː ko mɐʔɪnˌtɪndiˈhan]

- Where's the bathroom?: Nasaán ang banyo? [ˌnaːsɐˈʔan ʔaŋ ˈbaːnjo]

- Generic toast: Mabuhay! [mɐˈbuːhaɪ] [literally - "long live"]

- Do you speak English? Marunong ka bang magsalitâ ng Ingglés? [mɐˈɾuːnoŋ ka baŋ mɐɡsaliˈtaː naŋ ʔɪŋˈɡlɛs]

- It is fun to live. Masaya ang mabuhay! [mɐˈsaˈja ʔaŋ mɐˈbuːhaɪ]

- Magasawa sina Renz at Lalaine. "Renz and Lalaine are married"

- Tao ba si Richard Relloso? "Is Richard Relloso human?"

- Si Clarisse ay mahilig kumain. "Clarisse loves to eat"

Proverbs

Ang hindî marunong lumingón sa pinanggalingan ay hindî makaráratíng sa paroroonan. (José Rizal)

He who does not look back to his origin will never reach his destination.

Ang hindî magmahál sa kanyang sariling wika ay mahigít pa sa hayop at malansang isdâ. (José Rizal)

One who does not love his own language is worse than an animal and a putrid fish.

Hulí man daw at magalíng, nakákahábol pa rin. (Hulí man raw at magalíng, nakákahábol pa rin.)

It was said that even if he is late and excellent, he still catches up.

Magbirô ka na sa lasíng, huwág lang sa bagong gising.

Make fun of a drunk person, not to one who just woke up.

Ang sakít ng kalingkingan, ramdám ng buong katawán.

The pain of a small finger is felt by the whole body.

Nasa hulí ang pagsisisi.

Regret is in the end.

Pagkáhába-haba man ng prusisyón, sa simbahan pa rin ang tulóy.

Even the procession is long, its ending is the church.

Kung dî mádaán sa santong dasalan, daanin sa santong paspasan.

If it cannot be done through holy prayer, do it through holy speeding.

See also

References

- ^ a b c Omniglot.com Tagalog Retrieved September 30, 2009.

- ^ a b Philippine Census, 2000. Table 11. Household Population by Ethnicity, Sex and Region: 2000

- ^ http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=PH.

- ^ Andrew Gonzalez, FSC. "Language planning in multilingual countries: The case of the Philippines" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- ^ a b c d 1987 Philippine Constitution, Article XIV, Sections 6-9, Chanrobles Law Library, retrieved 2007-12-20

- ^ Zorc, David. 1977. The Bisayan Dialects of the Philippines: Subgrouping and Reconstruction. Pacific Linguistics C.44. Canberra: The Australian National University

- ^ Blust, Robert. 1991. The Greater Central Philippines hypothesis. Oceanic Linguistics 30:73–129

- ^ Mga Probisyong Pangwika sa Saligang-Batas

- ^ a b c d e Andrew Gonzalez (1998). "The Language Planning Situation in the Philippines" (PDF). Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 19 (5, 6): 487–488. doi:10.1080/01434639808666365. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Results from the 2000 Census of Population and Housing: Educational Characteristics of the Filipinos, National Statistics Office, March 18, 2005, retrieved 2008-01-21

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Results from the 2000 Census of Population and Housing: Population expected to reach 100 million Filipinos in 14 years, National Statistics Office, October 16, 2002, retrieved 2008-01-21

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Census:Languages of the United States" (PDF). United States. Retrieved 2007-05-16. (figure 3, page 2)

- ^ Statistics Canada 2006

- ^ 1897 Constitution of Biak-na-Bato, Article VIII, Filipiniana.net, retrieved 2008-01-16

- ^ 1935 Philippine Constitution, Article XIV, Section 3, Chanrobles Law Library, retrieved 2007-12-20

- ^ a b Manuel L. Quezon III, Quezon’s speech proclaiming Tagalog the basis of the National Language, quezon.ph, retrieved 2007-12-20

- ^ 1973 Philippine Constitution, Article XV, Sections 2-3, Chanrobles Law Library, retrieved 2007-12-20

- ^ EAC Issues Glossaries of Election Terms in Five Asian Languages Translations to Make Voting More Accessible to a Majority of Asian American Citizens. Election Assistance Commission. 06/20/2008.

- ^ a b Tagalog: Understanding the Language, lerc.educ.ubc.ca, retrieved 2008-09-26

- ^ Linda Trinh Võ; Rick Bonus (2002), Contemporary Asian American communities: intersections and divergences, Temple University Press, pp. 96, 100, ISBN 9781566399388

- ^ University of the Philippines College of Education (1971), "Philippine Journal of Education", Philippine Journal of Education, 50: 556

- ^ Perfecto T. Martin (1986), Diksiyunaryong adarna: mga salita at larawan para sa bata, Children's Communication Center, ISBN 9789711211189.

- ^ Op. cit. Trinh 2002, pp. 96, 100

- ^ Renato Perdon; Periplus Editions (2005), Renato Perdon (ed.), Pocket Tagalog Dictionary: Tagalog-English/English-Tagalog, Tuttle Publishing, pp. vi-vii, ISBN 9780794603458.

- ^ Michael G. Clyne (1997), Undoing and redoing corpus planning, Walter de Gruyter, p. 317, ISBN 9783110155099.

- ^ 2003 Yearbook of Jehovah's Witnesses p.155.

External links

- Tagalog Pocketbooks

- Tagalog dictionary

- Tagalog: A Brief Look at the National Language

- Searchable version of Calderon's English-Spanish-Tagalog dictionary.

- Calderon's English-Spanish-Tagalog dictionary for cell phone and PDA

- KalyeSpeak - Free Filipino Language Lessons Audio samples and Filipino lessons

- Tagalog-Sugbuanon Translator, an English to dialects of Tagalog and Sugbuanon languages Translator

- A Handbook and Grammar of the Tagalog Language by W.E.W. MacKinlay, 1905.

- Tagalog Translator Online Online dictionary for translating Tagalog from/to English, including expressions and latest headlines regarding the Philippines.