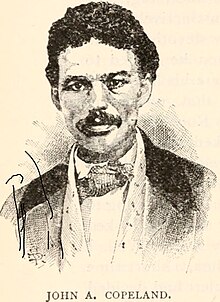

John Anthony Copeland Jr.

John Anthony Copeland, Jr. (1834–1859) was born a free black in Raleigh, North Carolina. In 1842, he moved north to Oberlin, Ohio, where he later attended Oberlin College and became involved in antislavery activities. He joined John Brown's unsuccessful raid on Harpers Ferry and was hung for his part in the raid on December 16, 1859.

Life

In September, 1858, he was one of the thirty-seven men involved in the incident known as the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue involving John Price, a runaway slave who was recaptured in accordance with the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act.

In September 1859 Copeland was recruited to John Brown's army by his uncle and fellow black raider, Lewis Sheridan Leary. John Brown together with twenty-one followers, sixteen white and five black men, captured the armory guards of Harpers Ferry and controlled the Federal arsenal. The raiders were pinned down by the Virginia militiamen until U.S. marines led by Robert E. Lee arrived to apprehend them.

Copeland's role in the Harpers Ferry assault was to seize control of Hall's Rifle Works, along with John Henry Kagi, a white raider. Kagi and several others were killed while trying to escape from the Rifle Works, across the Shenandoah River. Copeland was captured alive, in the middle of the river.

Copeland, Brown, and five others were captured and held for trial. At the trial, Copeland was found guilty of treason and murder and sentenced to death by hanging.

Copeland wrote to his family in terms which heavily reflected the religious influence of his Oberlin upbringing. In a December 16 letter, Copeland implored his family not to sorrow:

Why should you sorrow? Why should your hearts be racked with grief? Have I not everything to gain and nothing to lose by the change? I fully believe that not only myself but also all three of my poor comrades who are to ascend the same scaffold- (a scaffold already made sacred to the cause of freedom, by the death of that great champion of human freedom, Capt. JOHN BROWN) are prepared to meet our God.

Speaking of Copeland, the trial's prosecuting attorney said. . .

"From my intercourse with him I regard him as one of the most respectable persons we had. . . . He was a copper-colored Negro, behaved himself with as much firmness as any of them, and with far more dignity. If it had been possible to recommend a pardon for any of them it would have been this man Copeland as I regretted as much if not more, at seeing him executed than any other of the party."

Death

Copeland was executed at Charles Town, West Virginia, (then part of Virginia) on December 16, 1859. On his way to the gallows he reportedly said, "If I am dying for freedom, I could not die for a better cause -- I had rather die than be a slave!"

After the execution, the cadavers of Copeland and his fellow raider Shields Green were dug up and taken to a Winchester Medical College anatomy laboratory for dissection by students in Winchester, Virginia. Professor James Monroe of Oberlin College, a family friend of Copeland's from Oberlin, Ohio, searched for Copeland's body, but found Green's instead, and was unable to retrieve either body.[1] [2] "We visited the dissecting rooms. The body of Copeland was not there, but I was startled to find the body of another Oberlin neighbor whom I had often met upon our streets, a colored man named Shields Greene."[3]Likewise the body of Watson Brown was also "claimed" by Winchester Medical College as a teaching cadaver for students-an action for which the College was burned to the ground by Union troops in the Civil War. {Watson Brown was reburied beside his father in 1882}

A memorial service was held in Oberlin for Copeland, Green, and Lewis Sheridan Leary, who died during the raid, on December 25, 1859. A cenotaph was erected in 1865 in Westwood Cemetery to honor the three "citizens of Oberlin." The monument was moved in 1977 to Martin Luther King, Jr. Park on Vine Street in Oberlin.[4] The inscription reads:

- "These colored citizens of Oberlin, the heroic associates of the immortal John Brown, gave their lives for the slave. Et nunc servitudo etiam mortua est, laus deo.

- S. Green died at Charleston, Va., Dec. 16, 1859, age 23 years.

- J. A. Copeland died at Charleston, Va., Dec. 16, 1859, age 25 years.

- L. S. Leary died at Harper's Ferry, Va., Oct 20, 1859, age 24 years."

References

- ^ John Copeland: A Hero of Harpers Ferry, WCPN Radio, Aired February 21, 2001 (text and audio versions) accessed May 20, 2007.

- ^ John Brown's Body: Slavery, Violence, & the Culture of War. By Franny Nudelman. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8078-5557-X.)[1]

- ^ James Monroe, Oberlin College Website accessed June 4, 2007

- ^ Monument to the Oberlinians Who Participated in John Brown's Raid On Harpers Ferry accessed May 21, 2007

Further reading

- Abzug, Robert, Cosmos Crumbling: American Reform and the Religious Imagination. Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Altman, Susan, Extraordinary Black Americans. Children Press, 1989.

- Barrett, Tracy, Harpers Ferry: the story of John Brown’s raid. Millbrook Press, 1994.

- Brandt, Nat, The Town that Started the Civil War.

- Copeland, John A., Copeland Letters. See [2]

- Glaser, Jason, John Brown Raid on Harpers Ferry. Capstone Press, 2006.