N,N-Dimethyltryptamine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | N,N-Dimethyltryptamine |

| Routes of administration | Vaporization, Injection, Rectal, Insufflation, or Oral with MAOI |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.463 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H16N2 |

| Molar mass | 188.269 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.099g/ml g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 40 to 59 °C (104 to 138 °F) |

| |

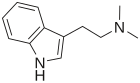

Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) is a naturally-occurring tryptamine and potent psychedelic drug, found not only in many plants, but also in trace amounts in the human body where its natural function is undetermined. Structurally, it is analogous to the neurotransmitter serotonin (5-HT) and other psychedelic tryptamines such as 5-MeO-DMT, bufotenin (5-OH-DMT), and psilocin (4-OH-DMT). DMT is created in small amounts by the human body during normal metabolism[1] by the enzyme tryptamine-N-methyltransferase. Many cultures, indigenous and modern, ingest DMT as a psychedelic in extracted or synthesized forms.[2] Pure DMT at room temperature is a clear or white to yellowish-red crystalline solid. A laboratory synthesis of DMT was first reported in 1931, and it was later found in many plants.[3]

Chemistry

DMT is a derivative of tryptamine with two additional methyl groups at the amine nitrogen atom. DMT was first extracted from the roots of Mimosa hostilis in 1946 by Brazilian ethnobotanist and chemist Gonçalves de Lima who named it Nigerine. DMT was first synthesized by a Canadian chemist Richard Manske in 1931.[3] DMT is usually used in its base form, but it is more stable as a salt, e.g. as a fumarate. In contrast to DMT's base, its salts are water-soluble. DMT in solution degrades relatively quickly and should be stored protected from air, light, and heat in a freezer.[citation needed] Highly pure DMT crystals, when evaporated out of a solvent and deposited upon glass, often produce small but highly defined white crystalline needles which, when viewed under intense light, will sparkle. The crystals appear colorless under high magnification.

Pharmacology

DMT is an agonist of the 5-HT2A receptor and also has been shown to activate the 5-HT2C receptor[4]. A study published in 2009 in Science shows that DMT is an agonist at the sigma-1 receptor.[5][6] It was speculated that DMT could be an endogenous ligand for this receptor. In this report, the concentration of DMT needed for sigma-1 activation is about 9.4 mg/L (50 µM). This concentration is higher than the average concentration measured in brain tissue or plasma, and is also about two orders of magnitude higher than that needed to activate the 5-HT2A receptor in vitro. In humans, effective hallucinogenic doses produce peak DMT plasma concentrations ranging between 12 and 90 µg/L and with an apparent volume of distribution of 36 to 55 L/kg.[7][8][9] The corresponding average molar plasma concentration of DMT is therefore in the range of 0.060-0.500 µM. However, the relatively high volume of distribution of DMT indicates significant movement of the drug from plasma into tissues and several reports have described the active accumulation of DMT and other tryptamines into rat brain following peripheral administration.[10][11][12][13][14] Similar active uptake processes in human brain may plausibly concentrate DMT within neurons by several-fold or more, resulting in local concentrations in the micromolar or higher range. Interestingly, the concentrations of DMT required to occupy a significant fraction of any of its known receptor binding sites are between 1,000 and 1,000,000-fold lower than the calculated synaptic concentration of other neurotransmitters. For example, using amperometric measurements, the synaptic concentration of dopamine was estimated to reach about 75 mM.[15] DMT also activated the trace amine associated receptor TAAR1 at the tested high concentration.[16]

Psychedelic properties

DMT occurs naturally in many species of plants often in conjunction with its close chemical relatives 5-MeO-DMT and bufotenin (5-OH-DMT).[17] DMT-containing plants are commonly used in several South American shamanic practices. It is usually one of the main active constituents of the drink ayahuasca[2], however ayahuasca is sometimes brewed without plants that produce DMT. It occurs as the primary active alkaloid in several plants including Mimosa hostilis, Diplopterys cabrerana, and Psychotria viridis. DMT is found as a minor alkaloid in snuff made from Virola bark resin in which 5-MeO-DMT is the main active alkaloid.[17] DMT is also found as a minor alkaloid in the beans of Anadenanthera peregrina and Anadenanthera colubrina used to make Yopo and Vilca snuff in which bufotenin is the main active alkaloid.[17][18] Psilocybin, the active chemical in psilocybin mushrooms can also be considered a close chemical relative[19] for the psilocybin molecule contains a DMT molecule at the end as with other close chemical relatives (4-Phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyl-tryptamine).

The psychotropic effects of DMT were first studied scientifically by the Hungarian chemist and psychologist Dr. Stephen Szára, who performed research with volunteers in the mid-1950s. Szára, who later worked for the US National Institutes of Health, had turned his attention to DMT after his order for LSD from the Swiss company Sandoz Laboratories was rejected on the grounds that the powerful psychotropic could be dangerous in the hands of a communist country.[20]

DMT is generally not active orally unless it is combined with an monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) such as a reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase A (RIMA), e.g., harmaline. Without a MAOI, the body quickly metabolizes orally administered DMT, and it therefore has no hallucinogenic effect unless the dose exceeds monoamine oxidase's metabolic capacity (very rare). Other means of ingestion such as smoking or injecting the drug can produce powerful hallucinations and entheogenic activity for a short time (usually less than half an hour), as the DMT reaches the brain before it can be metabolised by the body's natural monoamine oxidase. Taking a MAOI prior to smoking or injecting DMT will greatly prolong and potentiate the effects of DMT. If DMT is smoked, injected, or orally ingested with a MAOI, it can produce powerful entheogenic experiences including intense visuals, euphoria, even true hallucinations (perceived extensions of reality).[21]

Inhaled

A standard dose for smoked N,N-DMT is between 15–60 mg. This is generally smoked in a few successive breaths. The effects last for a short period of time, usually 5 to 30 minutes, dependent on the dose. The onset after inhalation is very fast (less than 45 seconds) and peak effects are reached within a minute. In the 1960s, some reportedly referred to DMT as "the businessman's trip"[22] due to the relatively short duration of vaporized, insufflated, or injected DMT. Although the smoke produced is described as harsh by some, it can be mixed with cannabis, herbs, or one of many smoking mixtures and be used in a pipe, a waterpipe (popularly known as a bong), or a vaporizer. This helps to improve the smoothness of the smoke, ultimately making the substance easier to ingest.

Insufflation

When DMT is insufflated, the duration is markedly increased, and some users report diminished euphoria but an intensified otherworldly experience.

Injection

Injected DMT produces an experience that is similar to inhalation in duration, intensity, and characteristics.

Oral ingestion

DMT is broken down by the digestive enzyme monoamine oxidase and is practically inactive if taken orally, unless combined with a MAOI. The traditional South American ayahuasca, or yage, is a tea mixture containing DMT and an MAOI.[2] There are a variety of recipes to this brew, but most commonly it is simply the leaves of Psychotria viridis (the source of DMT) and the vine Banisteriopsis caapi (the source of MAOI). Other DMT containing plants, including Diplopterys cabrerana, are sometimes used in ayahuasca in different areas of South America. Two common sources in the western US are Reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea) and Harding grass (Phalaris aquatica). These invasive grasses contain low levels of DMT and other alkaloids. In addition, Jurema (Mimosa hostilis) shows evidence of DMT content: the pink layer in the bark of this vine contains a high concentration of N,N-DMT. Taken orally with an appropriate MAOI, DMT produces a long lasting (over 3 hour), slow, deep metaphysical experience similar to that of psilocybin mushrooms, but more intense with a shorter duration.[2] MAOIs should be used with extreme caution as they can have lethal complications with some prescription drugs such as SSRI antidepressants, some over-the-counter drugs,[23] and many common foods.

Induced DMT experiences can include profound time-dilation, visual and auditory illusions, and other experiences that, by most firsthand accounts, defy verbal or visual description. Some users report intense erotic imagery and sensations and utilize the drug in a ritual sexual context.[2][24][25]

In a study conducted from 1990 through 1995, University of New Mexico psychiatrist Rick Strassman found that many volunteers injected with high doses of DMT had experiences with a perceived alien entity. Usually, the reported entities were experienced as the inhabitants of a perceived independent reality the subjects reported visiting while under the influence of DMT.[20]

In a September, 2009, interview with Examiner.com, Strassman described the effects on participants in the study: "A slew of biological markers went up in a dose-dependent manner when we administered pure intravenous DMT to a group of healthy experienced hallucinogen users – including prolactin, cortisol, beta-endorphin, heart rate, body temperature, oxytocin, core temperature. We also developing a new rating scale to quantify the subjective effects, based on Buddhist psychology, and this was quite sensitive and efficient. Subjectively, the most interesting results were that high doses of DMT seemed to allow the consciousness of our volunteers to enter into non-corporeal, free-standing, independent realms of existence inhabited by beings of light who oftentimes were expecting the “volunteers,” and with whom the volunteers interacted. While “typical” near-death and mystical states occurred, they were relatively rare."[26]

Rectal Administration: DMT can also be taken rectally. Dosage started at 200mg without an MAOI. Effects last 2 hours.[27]

Side effects

When DMT is vaporized, the vapor produced is often felt to be very harsh on the lungs. According to a "Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans" by Rick Strassman, "Dimethyltryptamine dose slightly elevated blood pressure, heart rate, pupil diameter, and rectal temperature, in addition to elevating blood concentrations of beta-endorphin, corticotropin, cortisol, and prolactin. Growth hormone blood levels rose equally in response to all doses of DMT, and melatonin levels were unaffected."[28]

Speculations

This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (October 2009) |

Several speculative and yet untested hypotheses suggest that endogenous DMT, produced in the human brain, is involved in certain psychological and neurological states. DMT is naturally produced in small amounts in the brain and other tissues of humans and other mammals.[29] Some believe it plays a role in mediating the visual effects of natural dreaming, and also near-death experiences, religious visions and other mystical states.[30] A biochemical mechanism for this was proposed by the medical researcher J. C. Callaway, who suggested in 1988 that DMT might be connected with visual dream phenomena, where brain DMT levels are periodically elevated to induce visual dreaming and possibly other natural states of mind.[31] A new hypothesis proposed is that in addition to being involved in altered states of consciousness, endogenous DMT may be involved in the creation of normal waking states of consciousness. It is proposed that DMT and other endogenous hallucinogens mediate their neurological abilities by acting as neurotransmitters at a sub class of the trace amine receptors; a group of receptors found in the CNS where DMT and other hallucinogens have been shown to have activity. Wallach further proposes that in this way waking consciousness can be thought of as a controlled psychedelic experience. It is when the control of these systems becomes loosened and their behavior no longer correlates with the external world that the altered states arise.[32]

Dr. Rick Strassman, while conducting DMT research in the 1990s at the University of New Mexico, advanced the theory that a massive release of DMT from the pineal gland prior to death or near death was the cause of the near death experience (NDE) phenomenon. Several of his test subjects reported NDE-like audio or visual hallucinations. His explanation for this was the possible lack of panic involved in the clinical setting and possible dosage differences between those administered and those encountered in actual NDE cases. Several subjects also reported contact with 'other beings', alien like, insectoid or reptilian in nature, in highly advanced technological environments[20] where the subjects were 'carried', 'probed', 'tested', 'manipulated', 'dismembered', 'taught', 'loved' and even 'raped' by these 'beings'.

In the 1950s, the endogenous production of psychoactive agents was considered to be a potential explanation for the hallucinatory symptoms of some psychiatric diseases as the transmethylation hypothesis[33] (see also adrenochrome). Unfortunately, this hypothesis does not account for the natural presence of endogenous DMT in otherwise normal humans, rats and other laboratory animals. The proposal by Dr. Callaway was, however, the first to suggest a useful function for the endogenous production of DMT: to facilitate the visual phenomenon of normal dreaming.

Writers on DMT include Terence McKenna, Jeremy Narby and Graham Hancock (in passages of Supernatural), though most scientists who study psychedelic drugs treat their writings with skepticism. McKenna writes of his DMT experiences with a decidedly less skeptical slant, often presuming that the drug's "intoxication" is indicative of realms of consciousness equally as valid as waking-life if not more so. [1] In his writings and speeches, he recounts encounters with entities he sometimes describes as "Self-Transforming Machine Elves" among equally colorful phrases. McKenna believed DMT to be a tool that could be used to enhance communication and allow for communication with other-worldly entities. Other users report visitation from external intelligences attempting to impart information. These Machine Elf experiences are said to be shared by many DMT users. From a researcher's perspective, perhaps best known is Dr. Rick Strassman's DMT: The Spirit Molecule (ISBN 0-89281-927-8);[34] Dr. Strassman speculated that DMT is made in the pineal gland, largely because the necessary constituents (see methyltransferases) needed to make DMT are found in the pineal gland.

Prohibition

United States

DMT is classified in the United States as a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970.

In December 2004, the Supreme Court lifted a stay thereby allowing the Brazil-based União do Vegetal (UDV) church to use a decoction containing DMT in their Christmas services that year. This decoction is a "tea" made from boiled leaves and vines, known as hoasca within the UDV, and ayahuasca in different cultures. In Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, the Supreme Court heard arguments on November 1, 2005 and unanimously ruled in February 2006 that the U.S. federal government must allow the UDV to import and consume the tea for religious ceremonies under the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

Canada

DMT is classified in Canada as a Schedule III drug.

France

DMT, along with most of its plant sources, is classified in France as a stupéfiant (Narcotic).

United Kingdom

DMT is classified in the United Kingdom as a Class A drug.

New Zealand

DMT is classified as a Class A drug in New Zealand.

Culture

In Brazil there are a number of religious movements based on the use of ayahuasca, usually in an animistic context that may be shamanistic, sometimes mixed with Christian imagery. There are four main branches using DMT-MAOI based sacraments in Brazil:

- Indigenous Brazilian. These are the oldest cultures in the whole of South America that continue to use ayahuasca or analogue brews, such as the ones made from Jurema in the Pernambuco, near Recife.

- Santo Daime ("Saint Give Unto Me") and Barquinha ("Little Boat"). A syncretic religion from Brazil. The former was founded by Raimundo Irineu Serra in the early 1930s, as an esoteric Christian religion with shamanic tendencies. The Barquinha was derived from this one.

- União do Vegetal (Union of Vegetal or UDV). Another Christian ayahuasca religion from Brazil, is a single unified organization with a democratic structure.

- Neo-shamans. There are some self-styled shamanic facilitators in Brazil and other South American countries that use ayahuasca or analogous brews in their rituals and séances.

See also

References

- ^ Barker SA, Monti JA and Christian ST (1981). N,N-Dimethyltryptamine: An endogenous hallucinogen. In International Review of Neurobiology, vol 22, pp. 83-110; Academic Press, Inc.

- ^ a b c d e Salak, Kira. ""HELL AND BACK"". National Geographic Adventure.

- ^ a b Jeremy Bigwood and Jonathan Ott (1977): "DMT", Head Magazine

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9768567

- ^ http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/323/5916/934

- ^ http://www.uwhealth.org/news/psychoactivecompoundactivatesmysteriousreceptor/14330

- ^ Callaway JC, McKenna DJ, Grob CS, Brito GS, Raymon LP, Poland RE, Andrade EN, Andrade EO and Mash DC (1999) Pharmacokinetics of hoasca alkaloids in healthy humans. J. Ethnopharmacol., 65, 243-256.

- ^ Riba J, Valle M, Urbano G, Yritia M, Morte A and Barbanoj MJ (2003) Human pharmacology of ayahuasca: Subjective and cardiovascular effects, monoamine metabolite excretion, and pharmacokinetics. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 306, 73-83.

- ^ Yritia M, Riba J, Ortuno J, Ramirez A, Castillo A, Alfaro Y, de la Torre R and Barbanoj MJ (2002) Determination of N,N-dimethyltryptamine and beta-carboline alkaloids in human plasma following oral administration of ayahuasca. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 779, 271-281.

- ^ Barker SA, Beaton JM, Christian ST, Monti JA and Morris PE (1982) Comparison of the brain levels of N,N-dimethyltryptamine and alpha, alpha, beta, beta-tetradeutero-N,N-dimethyltryptamine following intraperitoneal injection. The in vivo kinetic isotope effect. Biochem. Pharmacol., 31, 2513-2516.

- ^ Sangiah S, Gomez MV and Domino EF (1979) Accumulation of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in rat brain cortical slices. Biol. Psychiatry, 14, 925-936.

- ^ Sitaram BR, Lockett L, Talomsin R, Blackman GL and McLeod WR (1987) In vivo metabolism of 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine and N,N-dimethyltryptamine in the rat. Biochem. Pharmacol., 36, 1509-1512.

- ^ Takahashi T, Takahashi K, Ido T, Yanai K, Iwata R, Ishiwata K and Nozoe S (1985) [11C]-labeling of indolealkylamine alkaloids and the comparative study of their tissue distributions. Int. J. Appl. Radiat. Isot., 36, 965-969.

- ^ Yanai K, Ido T, Ishiwata K, Hatazawa J, Takahashi T, Iwata R and Matsuzawa T (1986) In vivo kinetics and displacement study of a carbon-11-labeled hallucinogen, N,N-[11C]dimethyltryptamine. Eur. J. Nucl. Med., 12, 141-146.

- ^ Colliver TL, Pyott SJ, Achalabun M, Ewing AG (2000) VMAT-mediated changes in quantal size and vesicular volume. J. Neurosci., 20, 5276-5282.

- ^ Bunzow JR, Sonders MS, Arttamangkul S; et al. (2001). "Amphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, lysergic acid diethylamide, and metabolites of the catecholamine neurotransmitters are agonists of a rat trace amine receptor". Mol. Pharmacol. 60 (6): 1181–8. PMID 11723224.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Anadenanthera: Visionary Plant Of Ancient South America By Constantino Manuel Torres, David B. Repke, 2006, ISBN 0789026422

- ^ Pharmanopo-Psychonautics: Human Intranasal, Sublingual, Intrarectal, Pulmonary and Oral Pharmacology of Bufotenine by Jonathan Ott, The Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, September 2001

- ^ Relation between DMT and other related compounds http://deoxy.org/t_thc.htm

- ^ a b c R.J. Strassman. "Chapter summaries". DMT: The Spirit Molecule. Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- ^ http://www.erowid.org/chemicals/dmt/dmt.shtml

- ^ http://www.drugfree.org/Portal/drug_guide/DMT

- ^ Callaway J.C. and Grob C.S. (1998). Ayahuasca preparations and serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a potential combination for adverse interaction. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 30(4): 367-369.

- ^ "2C-B, DMT, You and Me". Maps. Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- ^ "Entheogens & Visionary Medicine Pages". Miqel.com. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ A.L. Hippleheuser. "Dr. Rick Strassman interview: DMT and near-death experiences shed light on spirit-brain relationship". Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ^ NeuroSoup. "DMT: The Shamic Colonic Video". Retrieved 2009-10-05.

- ^ R.J. Strassman and C.R. Qualls (February 1994). "Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans". Arch Gen Psychiatry. 51 (2): 85–97. Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- ^ "Erowid DMT Vault: Journal Articles & Abstracts". Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ^ http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=104240746&sc=fb&cc=fp

- ^ Callaway J (1988). "A proposed mechanism for the visions of dream sleep". Med Hypotheses. 26 (2): 119–24. doi:10.1016/0306-9877(88)90064-3. PMID 3412201.

- ^ Wallach J (2008). "Endogenous hallucinogens as ligands of the trace amine receptors: A possible role in sensory perception". Med Hypotheses. in print (in print): in print. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2008.07.052. PMID 18805646.

- ^ Osmund H and Smythies JR (1952). Schizophrenia: A new approach. Journal of Mental Science 98:309-315.

- ^ Rick Strassman, DMT: The Spirit Molecule: A Doctor's Revolutionary Research into the Biology of Near-Death and Mystical Experiences, 320 pages, Park Street Press, 2001, ISBN 0-89281-927-8