Languages of the European Union

The languages of the European Union are languages used by people within the member states of the European Union. They include the twenty-three official languages of the European Union along with a range of others. The EU asserts that it is in favour of linguistic diversity and currently has a European Commissioner for Multilingualism, Leonard Orban.

In the European Union, language policy is the responsibility of member states and EU does not have a common language policy; European Union institutions play a supporting role in this field, based on the "principle of subsidiarity". Their role is to promote cooperation between the member states and to promote the European dimension in the member states language policies. The EU encourages all its citizens to be multilingual; specifically, it encourages them to be able to speak two languages in addition to their mother tongue. Though the EU has very limited influence in this area as the content of educational systems is the responsibility of individual member states, a number of EU funding programmes actively promote language learning and linguistic diversity.[1]

According to statistics the majority of EU citizens speaks German[citation needed], while the absolute majority can understand English and speak German, English, French or Italian as mother languages.

French is an official language common to the three cities that are political centres of the Union: Brussels (Belgium), Strasbourg (France) and Luxembourg city (Luxembourg), while Catalan, Galician and (in the Baltic states) Russian are the most widely used non-recognised languages in the EU.

Official EU languages

The official languages of the European Union, as stipulated in the latest amendment (as of 1 January 2007[update]) of the Regulation No 1 determining the languages to be used by the European Economic Community of 1958[2] are:[3]

| Language | Official in (de jure or de facto) | Since |

|---|---|---|

| Bulgarian | Bulgaria | 2007 |

| Czech | Czech Republic | 2004 |

| Danish | Denmark | 1973 |

| Dutch | Netherlands and Belgium | 1958 |

| English | Ireland, Malta and United Kingdom | 1958 |

| Estonian | Estonia | 2004 |

| Finnish | Finland | 1995 |

| French | Belgium, France, Italy1 and Luxembourg | 1958 |

| German | Austria, Belgium, Germany, Italy2 and Luxembourg | 1958 |

| Greek | Cyprus, Greece and Italy3 | 1981 |

| Hungarian | Hungary, Romania4 and Slovakia5 | 2004 |

| Irish | Ireland and United Kingdom6 | 2007 |

| Italian | Italy and Slovenia7 | 1958 |

| Latvian | Latvia | 2004 |

| Lithuanian | Lithuania | 2004 |

| Maltese | Malta | 2004 |

| Polish | Poland | 2004 |

| Portuguese | Portugal | 1986 |

| Romanian | Romania | 2007 |

| Slovak | Slovakia | 2004 |

| Slovene | Slovenia and Italy8 | 2004 |

| Spanish | Spain | 1986 |

| Swedish | Finland and Sweden | 1995 |

1Region of Aosta Valley

2Province of Bolzano-Bozen

3Provinces of Apulia and Reggio Calabria

4Can be used in local administration along with Romanian in every municipality, city or commune that has over 20% Hungarians.

8Region of Friuli Venezia Giulia

The number of member states exceeds the number of official languages, as several national languages are shared by two or more countries. Namely, Dutch is official in the Netherlands and Belgium, French in France, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Italian province of Aosta Valley, German in Germany, Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Italian province of Bolzano-Bozen, and Greek in Greece, Cyprus and the Italian provinces of Apulia and Reggio Calabria. English and Swedish are also shared, the former by the United Kingdom, Ireland and Malta and the latter by Sweden and Finland, but the fact that they are co-official in Ireland, Malta and Finland with languages unique to those countries, namely Irish, Maltese and Finnish respectively, means that the overall ratio of member states to national languages is unaffected. Also Slovene is official in the easternmost part of the Italian region of Friuli Venezia Giulia.

Furthermore, not all national languages have been accorded the status of official EU languages. These include Luxembourgish, an official language of Luxembourg since 1984, and Turkish, an official language of Cyprus.

All languages of the EU are also working languages.[5] Documents which a Member State or a person subject to the jurisdiction of a Member State sends to institutions of the Community may be drafted in any one of the official languages selected by the sender. The reply shall be drafted in the same language. Regulations and other documents of general application shall be drafted in the twenty-three official languages. The Official Journal of the European Union shall be published in the twenty-three official languages.

Legislation and documents of major public importance or interest are produced in all twenty-three official languages, but that accounts for a minority of the institutions' work. Other documents (e.g. communications with the national authorities, decisions addressed to particular individuals or entities and correspondence) are translated only into the languages needed. For internal purposes the EU institutions are allowed by law to choose their own language arrangements. The European Commission, for example, conducts its internal business in three languages, English, French and German (sometimes called procedural languages), and goes fully multilingual only for public information and communication purposes. The European Parliament, on the other hand, has Members who need working documents in their own languages, so its document flow is fully multilingual from the outset.[6] Non-institutional EU bodies are not legally obliged to make language arrangement for all the 23 languages (Kik v. OHIM, Case C-361/01, 2003 ECJ I-8283).

According to the EU's English language website,[7] the cost of maintaining the institutions' policy of multilingualism (i.e. the cost of translation and interpretation) was €1123 million in 2005, which is 1% of the annual general budget of the EU, or €2.28 per person per year.

Maltese

Although Maltese is an official language, the Council set up a transitional period of three years from 1 May 2004, during which the institutions were not obliged to draft all acts in Maltese.[8] It was agreed that the Council could extend this transitional period by an additional year, but decided not to.[9] All new acts of the institutions were required to be adopted and published in Maltese from 30 April 2007.

Irish

When Ireland joined the EEC (now the EU) in 1973, Irish was accorded “Treaty Language” status. This meant that the founding EU Treaty was restated in Irish. Irish was also listed in that Treaty and all subsequent EU Treaties as one of the authentic languages of the Treaties.[10] As a Treaty Language, Irish was an official procedural language of the European Court of Justice.[11] It was also possible to correspond in written Irish with the EU Institutions.

However, despite being the first official language of Ireland and having been accorded minority-language status in Northern Ireland, Irish was not made an official working language of the EU until 1 January 2007. On that date an EU Council Regulation making Irish an official working language of the EU came into effect.[12] This followed a unanimous decision on 13 June 2005 by EU foreign ministers that Irish would be made the 21st official language of the EU.[13] However, a derogation stipulates that not all documents have to be translated into Irish as is the case with the other official languages.[14][15]

The new Regulation means that legislation approved by both the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers will now be translated into Irish, and interpretation from Irish will be available at European Parliament plenary sessions and some Council meetings. The cost of translation, interpretation, publication and legal services involved in making Irish an official EU language is estimated at just under €3.5 million a year.[16] The derogation will be reviewed after four years and every five years thereafter. Irish is the only official language of the Union that is not the most widely spoken language in any Member State. According to the 2006 Irish census figures, there are 1.66 million speakers of Irish in Ireland out of a population of 4.24 million, though only 538,500 use Irish on a daily basis, and just 53,500 speak it on a daily basis outside the education system.[17]

Linguistic classification

The majority of the official languages of the European Union belong to the Indo-European language family, the three dominant subfamilies being the Germanic, Romance and Slavic languages. Germanic languages are widely spoken in central and northern areas of the EU and include Danish, Dutch, English, German, and Swedish. Romance languages are spoken in western and southern regions and include French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, and Spanish. The Slavic languages are to be found in the eastern regions and include Bulgarian, Czech, Polish, Slovak, and Slovene. The Baltic languages; Latvian and Lithuanian, the Celtic language; Irish, and Greek are also of Indo-European origin. Outside the Indo-European family, Estonian, Finnish, and Hungarian are Finno-Ugric languages while Maltese is the only Afroasiatic language with official status in the EU. All official EU languages are written with variations of the Latin alphabet, except Greek (written with the Greek alphabet) and Bulgarian (written in the Cyrillic alphabet).

No official recognition

According to the Euromosaic study, a number of regional or minority languages are spoken within the EU that do not have official recognition at EU level. Some of them may have some official status within the member state and count many more speakers than some of the lesser-used official languages. The official languages of EU are in bold. In the list, constructed languages or what member states deem as mere dialects of an official language of member states are not included. It should be noted that many of these alleged dialects are widely viewed by linguists as separate languages, however. These include Scots (the Germanic language descended from Anglo-Saxon, not the Celtic language known as Scots Gaelic) and several Romance languages spoken in Italy such as Western Lombard, Eastern Lombard, Venetian, Neapolitan, and Sicilian.

Spanish autonomous languages

The Spanish governments have sought to give some official status in the EU for the languages of the Autonomous communities of Spain, Catalan, Galician and Basque. The 667th Council Meeting of the Council of the European Union in Luxembourg on 13 June 2005 decided to authorise limited use at EU level of languages recognised by Member States other than the official working languages. The Council granted recognition to "languages other than the languages referred to in Council Regulation No 1/1958 whose status is recognised by the Constitution of a Member State on all or part of its territory or the use of which as a national language is authorised by law." The official use of such languages will be authorised on the basis of an administrative arrangement concluded between the Council and the requesting Member State.[18]

Although Basque, Catalan and Galician are not nation-wide official languages in Spain, as co-official languages in the respective regions (pursuant to Spain's constitution, among other documents) they are eligible to benefit from official use in EU institutions under the terms of the 13 June 2005 resolution of the Council of the European Union. The Spanish government has assented to the provisions in respect of these languages. Leonese is not official in any Autonomous Community of Spain, and it just holds a "special protection status" by the Castile and León.

The status of Catalan, spoken by over 9 million EU citizens (1.8% of the total), has been the subject of particular debate. On 11 December 1990, the use of Catalan was the subject of a European Parliament Resolution (resolution A3-169/90 on languages in the (European) Community and the situation of Catalan (OJ-C19, 28 January 1991).

On 16 November 2005, the Committee of the Regions President Peter Straub signed an agreement with the Spanish Ambassador to the EU, Carlos Sagües Bastarreche, approving the use of Spanish regional languages in an EU institution for the first time in a meeting on that day, with interpretation provided by European Commission interpreters.[19][20]

On 3 July 2006, the European Parliament’s Bureau approved a proposal by the Spanish State to allow citizens to address the European Parliament in Basque, Catalan and Galician, two months after its initial rejection.[21][22]

On 30 November 2006, the European Ombudsman, Nikiforos Diamandouros, and the Spanish ambassador in the EU, Carlos Bastarreche, signed an agreement in Brussels to allow Spanish citizens to address complaints to the European Ombudsman in Basque, Catalan and Galician, all three co-official languages in Spain.[23] According to the agreement, a translation body, which will be set up and financed by the Spanish government, will be responsible for translating complaints submitted in these languages. In turn, it will translate the Ombudsman's decisions from Spanish into the language of the complainant. Until such a body is established the agreement will not become effective.

Luxembourgish and Turkish

Luxembourgish, an official language of Luxembourg, and Turkish, an official language of Cyprus, have not yet used this provision. In response to a written parliamentary question tabled following the 13 June 2005 resolution on official use of regional languages, the UK Minister for Europe, Douglas Alexander, stated on 29 June 2005 that "The Government have no current plans to make similar provisions for UK languages."[24]

Romani

Despite having lived in Europe for over seven hundred years, suffering the Porajmos of the twentieth century, and still numbering over two million people in the EU alone[25], the Romani people are some of the most disenfranchised people in the EU as neither the Romani language nor any of the Indo-Iranian languages are official in any EU member state or polity, their mass media and educational institution presences are near-negligible, they have immense incarceration rates, and they have substantially lower wages, education, life expectancy, and employment.[26]

Russian

This article's factual accuracy is disputed. (July 2009) |

Though not an official language of the European Union, Russian is widely spoken in some of the newer member states of the Union that were formerly in the Eastern bloc. Russian is the native language of about 1.3 million Baltic Russians residing in Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania, as well as a sizeable community in Germany. Russian is also understood by many ethnic Latvians, Estonians and Lithuanians, since, as official language of the Soviet Union, it was a compulsory subject in these countries during the Soviet era. Russian may be understood by older people in the Central Europe due to compulsory Russian education in the Eastern bloc. It is the 8th most spoken language in the EU. About 7% of all EU citizens speak or understand Russian to some extent.

Esperanto

The European Parliament party Europe – Democracy – Esperanto seeks to establish Esperanto as the official language of the EU.

Migrant languages

A wide variety of languages from other parts of the world are spoken by immigrant communities in EU countries. Turkish is spoken as a first language by an estimated 2% of the population in Belgium and the western part of Germany and by 1% in The Netherlands. Other widely-used migrant languages include Maghreb Arabic (and others) (mainly in France, Belgium, The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Spain and Cyprus), Hindi, Urdu, Bengali and Punjabi spoken by immigrants from the Indian sub-continent in the United Kingdom, while Balkan languages are spoken in many parts of the EU by migrants and refugees who have left the region as a result of the recent wars and unrest there.

There are large Chinese communities in France, UK, Spain, Italy and other countries. Some countries have Chinatowns. Old and recent Chinese migrants speak various Chinese dialects, notably Cantonese and other southern Chinese tongues. However, Mandarin is becoming increasingly more prevalent due to the opening up of the People's Republic of China and is also, at least, one of the Chinese language varieties spoken by Chinese immigrants.

Many immigrant communities in the EU have been in place for several generations now and their members are bilingual, at ease both in the local language and in that of their community. [1]

Language skills of citizens

The following tables are based on "Special Eurobarometer 243" of the European Commission with the title "Europeans and their Languages" (summary full text), published on February 2006 with research carried out in November and December 2005. The survey was published before the 2007 Enlargement of the European Union, when Bulgaria and Romania acceded. This is a poll, not a census. 28,694 citizens with a minimum age of 15 were asked in the 25 member-states as well as in the future member-states (Bulgaria, Romania) and the candidate countries (Croatia, Turkey) at the time of the survey. Only citizens, not immigrants, were asked.

The first table shows what proportion of citizens said that they could have a conversation in each language as their mother tongue and as a second language or foreign language (only the languages with at least 2% of the speakers are listed):

Template:Languages of the European Union

At 18% of the total number of speakers, German is the most widely spoken mother tongue, while English is the most widely spoken language at 51%. 100% of Hungarians, 100% of Portuguese, and 99.5% of Greeks speak their state language as their mother tongue.

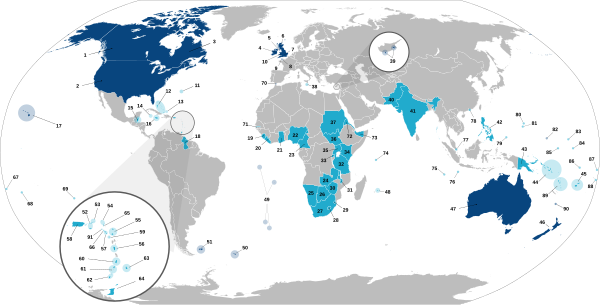

The knowledge of foreign languages varies considerably in the specific countries, as the table below shows. The five most used, and spoken second or foreign languages in the EU are English, German, French, Russian and Spanish followed by Italian. The cases coloured in blue means that the language is one/the official language of the country and dark blue means it is the main language spoken in the country.

| Country (EU27) |

English as a language other than mother tongue |

German as a language other than mother tongue |

French as a language other than mother tongue |

Spanish as a language other than mother tongue |

Italian as a language other than mother tongue |

Russian as a language other than mother tongue |

Polish as a language other than mother tongue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58% | 4% | 10% | 4% | 8% | 2% | 0% | |

| 59% | 27% | 48% | 6% | 3% | 0% | 0% | |

| 23% | 12% | 9% | 2% | 1% | 35% | 0% | |

| 76% | 5% | 12% | 2% | 4% | 2% | 0% | |

| 24% | 28% | 2% | 0% | 1% | 20% | 3% | |

| 86% | 58% | 12% | 5% | 1% | 1% | 0% | |

| 46% | 22% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 66% | 0% | |

| 63% | 18% | 3% | 2% | 1% | 2% | 0% | |

| 36% | 8% | 6% | 13% | 5% | 0% | 0% | |

| 56% | 9% | 15% | 4% | 3% | 7% | 1% | |

| 48% | 9% | 8% | 0% | 4% | 3% | 0% | |

| 23% | 25% | 2% | 1% | 2% | 8% | 0% | |

| 5% | 7% | 20% | 4% | 1% | 1% | 0% | |

| 29% | 5% | 14% | 4% | 1% | 0% | 0% | |

| 39% | 14% | 2% | 1% | 0% | 70% | 2% | |

| 32% | 19% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 80% | 15% | |

| 60% | 88% | 90% | 1% | 5% | 0% | 0% | |

| 88% | 3% | 17% | 3% | 66% | 0% | 0% | |

| 87% | 70% | 29% | 5% | 1% | 0% | 0% | |

| 29% | 20% | 3% | 1% | 1% | 26% | 0% | |

| 32% | 3% | 24% | 9% | 1% | 0% | 0% | |

| 29% | 6% | 24% | 3% | 4% | 0% | 0% | |

| 32% | 32% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 29% | 4% | |

| 57% | 50% | 4% | 2% | 15% | 2% | 0% | |

| 27% | 2% | 12% | 10% | 2% | 1% | 0% | |

| 89% | 30% | 11% | 6% | 2% | 1% | 1% | |

| 7% | 9% | 23% | 8% | 2% | 1% | 0% | |

| Candidate countries: | |||||||

| 49% | 34% | 4% | 2% | 14% | 4% | 0% | |

| 17% | 4% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 0% | |

Source: [2]

56% of citizens in the EU Member States are able to hold a conversation in one language apart from their mother tongue. This is 9 points more than was perceived in 2001 among the 15 Member States at the time [3]. 28% of the respondents state that they speak two foreign languages well enough to have a conversation. Still, almost half of the respondents, 44%, admit not knowing any other language than their mother tongue. Approximately 1 in 5 Europeans can be described as an active language learner, i.e. someone who has recently improved his/her language skills or intends to do so over the following 12 months.

English remains the most widely spoken foreign language throughout Europe. 38% of EU citizens state that they have sufficient skills in English to have a conversation (excluding the citizens of the United Kingdom and Ireland, the two English-speaking countries). 14% of Europeans indicate that they know either French or German along with their mother tongue. French is most commonly studied and used in Southern Europe, especially in Mediterranean countries, in Germany, Romania, the UK and Ireland while German is commonly studied and used in the Benelux countries, in Scandinavia and in the newer EU member states. Spanish is most commonly studied in France, Italy, Luxembourg and Portugal. In 19 out of 29 countries polled, English is the most widely known language apart from the mother tongue, this being particularly the case in Sweden (89%), Malta (an ex-British colony that is also part of the Commonwealth of Nations as well) (88%), the Netherlands (87%), and Denmark (86%), while German and French is so in three countries. Moreover, the citizens of the EU think they speak English at a better level than any other second or foreign language. 77% of EU citizens believe that children should learn English and that it's considered the number one language to learn in all countries where the research conducted but the United Kingdom, Ireland and Luxembourg.

All in all, English either as a mother tongue or as a second/foreign language is spoken by 51% of EU citizens, followed by German with 32% and French with 28% of those asked.

With the enlargement of the European Union, the balance between French and German is slowly changing. Clearly more citizens in the new Member States master German (23% compared with 12% in the EU15) while their skills in French and Spanish are scarce (3% and 1% respectively compared with 16% and 7% among the EU15 group). A notable exception is Romania, where 24% of the population speaks French as a foreign language compared to 6% who speaks German as a foreign language (also 4% of the population speaks Italian as a foreign language, while 3% of the population speaks Spanish as a foreign language).

At the same time the balance is being changed in the opposite direction by the growth of the population of French and the decline of that of German.

It is worth pointing out that language skills are unevenly distributed both over the geographical area of Europe and over sociodemographic groups. Reasonably good language competences are perceived in relatively small Member States with several state languages, lesser used native languages or "language exchange” with neighbouring countries. This is the case for example in Luxembourg where 92% speak at least two languages. Those who live in Southern European countries or countries where one of the major European languages is a state language appear to have moderate language skills. Only 5% of Turkish, 13% of Irish, 16% of Italians, 17% of Spanish and 18% from the UK speak at least two languages apart from their mother tongue. A "multilingual" European is likely to be young, well-educated or still studying, born in a country other than the country of residence, who uses foreign languages for professional reasons and is motivated to learn. Consequently, it seems that a large part of European society is not enjoying the advantages of multilingualism.

Free language lessons (26%), flexible language courses that suit one’s schedule (18%) and opportunities to learn languages in a country where it is spoken natively (17%) are considered to be the main incentives encouraging language learning. Group lessons with a teacher (20%), language lessons at school (18%), “one-to-one” lessons with a teacher and long or frequent visits to a country where the language is spoken are considered to be the most suitable ways to learn languages.

Policy

The European Union ability for legislative acts and other initiatives on language policy is based legally in the provisions in the Treaties of the European Union. In the EU, language policy is the responsibility of member states and European Union does not have a "common language policy". Based on the "principle of subsidiarity", European Union institutions play a supporting role in this field, promoting cooperation between the member states and promoting the European dimension in the member states language policies, particularly through the teaching and dissemination of the languages of the member states (Article 149.2).[27][28] The rules governing the languages of the institutions of the Community shall, without prejudice to the provisions contained in the Statute of the Court of Justice, be determined by the Council, acting unanimously (Article 290). All languages, in which was originally drawn up or was translated due to enlargement, are legally equally authentic. Every citizen of the Union may write to any of the EU institutions or bodies in one of the these languages and have an answer in the same language (Article 314).

In the Charter of Fundamental Rights, a legally non-binding text, the EU declares that it respects linguistic diversity (Article 22) and prohibits discrimination on grounds of language (Article 21). Respect for linguistic diversity is a fundamental value of the European Union, in the same way as respect for the person, openness towards other cultures, tolerance and acceptance of other people.

Initiatives

Beginning with the Lingua programme in 1990, the European Union invests more than €30 million a year (out of a €120 billion EU budget) promoting language learning through the Socrates and Leonardo da Vinci programmes in: bursaries to enable language teachers to be trained abroad, placing foreign language assistants in schools, funding class exchanges to motivate pupils to learn languages, creating new language courses on CDs and the Internet and projects that raise awareness of the benefits of language learning.

Through strategic studies, the Commission promotes debate, innovation and the exchange of good practice. In addition, the mainstream actions of Community programmes which encourage mobility and transnational partnerships motivate participants to learn languages.

Youth exchanges, town twinning projects and the European Voluntary Service also promote multilingualism. Since 1997, the Culture 2000 programme has financed the translation of around 2,000 literary works from and into European languages.

The new programmes proposed for implementation for the financial perspective 2007-2013 (Culture 2007, Youth in Action and Lifelong Learning) will continue and develop this kind of support.

In addition, the EU provides the main financial support to the European Bureau for Lesser-Used Languages (a non-governmental organisation which represents the interests of the over 40 million citizens who belong to a regional and minority language community), and for the Mercator networks of universities active in research on lesser-used languages in Europe. Following a request from the European Parliament, the Commission in 2004 launched a feasibility study on the possible creation of a new EU agency, "European Agency for Language Learning and Linguistic Diversity". The study concludes that there are unmet needs in this field, and proposes two options: creating an agency or setting up a European network of "Language Diversity Centres". The Commission believes that a network would be the most appropriate next step and, where possible, should build on existing structures; it will examine the possibility of financing it on a multi-annual basis through the proposed Lifelong Learning programme. Another interesting step would be to translate important public websites, such as the one of the European Central Bank, or Frontex web site also, in at least one other language than English.

Although not an EU treaty, most EU member states have ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[29]

To encourage language learning, the EU supported the Council of Europe initiatives for European Year of Languages 2001 and the annual celebration of European Day of Languages on 26 September.

To encourage the member states to cooperate and to disseminate best practice the Commission has issued a Communication on 24 July 2003, on Promoting Language Learning and Linguistic Diversity: an Action Plan 2004 - 2006 (summary) and a Communication on 22 November 2005, on A New Framework Strategy for Multilingualism (summary).

From 22 November 2004, the European Commissioner for Education and Culture portfolio included an explicit reference to languages and became European Commissioner for Education, Training, Culture and Multilingualism with Ján Figeľ at the post. From 1 January 2007, the European Commission has a special portfolio on languages, European Commissioner for Multilingualism. The post is currently held by Leonard Orban.

EU devotes a specialised subsite of its "Europa" portal to languages, the EUROPA Languages portal.

See also

- European languages

- European Commissioner for Multilingualism– Leonard Orban

- Translation Centre for the Bodies of the European Union (CDT) - Inter-Active Terminology for Europe (IATE)

- European Day of Languages– 26 September

- Linguistic issues concerning the euro

- English language in Europe

References

- ^ EUROPA - Education and Training - Action Plan Promoting language learning and linguistic diversity

- ^ Council Regulation (EC) No 1791/2006 of 20 November 2006, Official Journal L 363 of December 12, 2006. Retrieved on 2 February 2007.

- ^ EUROPA - Education and Training - Languages in Europe

- ^ http://www.hhrf.org/htmh/en/?menuid=0406

- ^ EUROPA-Languages-Translation-Policies

- ^ Europa:Languages and Europe. FAQ: Is every document generated by the EU translated into all the official languages?, Europa portal. Retrieved on 6 February 2007.

- ^ Europa:Languages and Europe. FAQ: What does the EU's policy of multilingualism cost?, Europa portal. Retrieved on 6 February 2007.

- ^ http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2004:169:0001:0002:EN:PDF

- ^ http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2006:329:0001:0002:EN:PDF

- ^ Taoiseach Website Press Release dated 1 January 2007

- ^ Deirdre Fottrell, Bill Bowring - 1999 Minority and Group Rights in the New Millennium.

- ^ See: Council Regulation (EC) No 920/2005.]

- ^ http://ue.eu.int/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/en/gena/85437.pdf Decision made at 667th Meeting of the Council of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- ^ http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/en/oj/2005/l_156/l_15620050618en00030004.pdf

- ^ http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/expert/infopress_page/008-828-269-9-39-901-20050928IPR00827-26-09-2005-2005-IE-false/default_en.htm

- ^ EU to hire 30 Irish translators at cost of €3.5 million

- ^ http://www.cso.ie/census/documents/Final%20Principal%20Demographic%20Results%202006.pdf

- ^ http://ue.eu.int/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/en/gena/85437.pdf

- ^ EUROPA-Languages-News-Spanish regional languages used for the first time

- ^ http://www.cor.europa.eu/en/press/press_05_11125.html

- ^ MERCATOR :: News

- ^ Catalan government welcomes European Parliament language move

- ^ European Ombudsman Press Release No. 19/2006 30.11.2006

- ^ House of Commons Hansard Written Answers for 29 Jun 2005 (pt 13)

- ^ Ethnologue

- ^ Euromosaic

- ^ Consolidated version of the Treaty establishing the European Community, Articles 149 to 150, Official Journal C 321E of 29 December 2006. Retrieved on 1 February 2007.

- ^ European Parliament Fact Sheets: 4.16.3. Language policy, European Parliament website. Retrieved on 3 February 2007.

- ^ [http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/Commun/ChercheSig.asp?NT=148&CM=8&DF=&CL=ENG European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages CETS No.: 148]

Further reading

- Michele Gazzola (2006) "Managing Multilingualism in the European Union: Language Policy Evaluation for the European Parliament", Language Policy, vol. 5, n. 4, p. 393-417.

- Hogan-Brun, Gabrielle and Stefan Wolff. 2003. Minority Languages in Europe: Frameworks, Status, Prospects. Palgrave. ISBN 1403903964

- Nic Craith, Máiréad. 2005. Europe and the Politics of Language: Citizens, Migrants and Outsiders. Palgrave. ISBN 1403918333

- Richard L. Creech, "Law and Language in the European Union: The Paradox of a Babel 'United in Diversity'" (Europa Law Publishing: Groningen, 2005) ISBN 90-76871-43-4

- Shetter, William Z., EU Language Year 2001: Celebrating diversity but with a hangover, Language Miniature No 63.

- Shetter, William Z., Harmony or Cacophony: The Global Language System, Language Miniature No 96.

External links

Official EU webpages

- Europa: Languages and Europe - The European Union portal on languages

- European Parliament Fact Sheets: 4.16.3. Language policy

- European Commission > Education and Training > Policy Areas > Languages

- Languages in the EU - Hear and see examples of the official EU languages

- European Commissioner for Multilingualism - Leonard Orban

- European Commission Directorate-General for Education and Culture (DG EAC)

- European Commission Directorate-General for Translation (DGT)

- European Commission Directorate-General for Interpretation (former SCIC)

- European Union Publications Office

- European Union interinstitutional style guide

- The process of creating documents in this multilingual environment (PDF)

News

- EurActiv.com - Languages and Culture - news site

- Eurolang news agency covering lesser-used languages in the EU.

Other

- The European Federation of National Institutions for Language (EFNIL)

- The European Bureau for Lesser-Used Languages (EBLUL) - a EU funded NGO on lesser-used languages in the EU.

- Mercator - networks of universities active in research on lesser-used languages in Europe

- ADUM - information on minority languages EU programmes.

- MinoLa - Minority Languages in the European Union

- Web del Parlament Europeu - Unofficial Catalan version of the EU Parliament Web