Axis powers

Axis Powers | |

|---|---|

| 1939–1945 | |

| Location of Zander | |

| Status | Military alliance |

| Historical era | World War II |

| September 27 1939 | |

| November 25, 1936 | |

| May 22, 1939 | |

| 1945 | |

The Axis powers (German: Achsenmächte, Italian: Potenze dell'Asse, Japanese: 枢軸国 Suujikukoku, Bulgarian: "Сили от Оста"), also known as the Axis alliance, Axis nations, Axis countries, or just the Axis, comprised the countries that were opposed to the Allies during World War II.[1] The three major Axis powers—Germany, Japan, and Italy—were part of a military alliance on the signing of the Tripartite Pact in September 1940, which officially founded the Axis powers. At their zenith, the Axis powers ruled empires that dominated large parts of Europe, Africa, East and Southeast Asia and the Pacific Ocean, but World War II ended with their total defeat and dissolution. Like the Allies, membership of the Axis was fluid, and some nations entered and later left the Axis during the course of the war.[2]

Origins

The term "axis" is believed to have been first coined by Hungary's fascist prime minister Gyula Gömbös who advocated an alliance of Germany, Hungary, and Italy and worked as an intermediary between Germany and Italy to lessen differences between the two countries to achieve such an alliance.[3] Gömbös' sudden death in 1936 while negotiating with Germany in Munich and the arrival of a non-fascist successor to him ended Hungary's initial involvement in pursuing a trilateral axis, but the lessening of differences between Germany and Italy would lead to a bilateral axis being formed.[3]

In November 1936, the term "axis" was first officially used by Italian dictator Benito Mussolini when he spoke of a Rome-Berlin axis arising out of the treaty of friendship signed between Italy and Germany on 25 October 1936, around which the other states of Europe (and of the world) would revolve. This treaty was forged when Italy, originally opposed to Nazi Germany, was faced with opposition to its war in Abyssinia from the League of Nations and received support from Germany. Later, in May 1939, this relationship transformed into an alliance, which Mussolini called the "Pact of Steel".

The "Axis powers" formally took the name after the Tripartite Pact was signed by Germany, Italy and Japan on September 27, 1940 in Berlin, Germany. The pact was subsequently joined by Hungary (November 20, 1940), Romania (November 23, 1940), Slovakia (November 24, 1940) and Bulgaria (March 1, 1941). The Italian name Roberto briefly acquired a new meaning from "Rome-Berlin-Tokyo" between 1940 and 1945. Its most militarily powerful members were Germany and Japan. These two nations had also signed the Anti-Comintern Pact with each other as allies before the Tripartite Pact in 1936.

Participating nations

Belligerents

Germany

Germany was unofficially the leader of the Axis powers as it had the largest and most technologically-advanced armed forces of the Axis powers. Germany was ruled at this time by Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist German Workers' Party.

German citizens felt that their country had been humiliated as a result of the Treaty of Versailles at the end of World War I in which Germany was forced to pay enormous reparations payments, and forfeit German-populated territories and its colonies. German nationalists blamed the country's defeat on pacifists, Communists, and Jews.[citation needed] The Germans had to pay large reparations which placed pressure on the German economy leading to hyperinflation during the early 1920s. In 1923, the French occupied the Ruhr region as a result of late payments leading to greater feelings of discontent. Although Germany began to improve economically in the mid-1920s, the Great Depression created more economic hardship and a rise in political forces that advocated radical solutions to Germany's woes. The Nazis under Adolf Hitler followed and promoted the nationalist belief that Germany had been betrayed by Jews and Communists and promised to rebuild Germany as a major power and to create a Greater Germany which would include Alsace-Lorraine, Austria, Sudetenland, and other German-populated territories in Europe. In addition to this, the Nazis aimed to occupy non-German territory of Poland, Baltic countries, and the Soviet Union to colonize with Germans as part of the Nazi policy of seeking Lebensraum ("living space") in eastern Europe.

Germany renounced the Versailles treaty in 1935 and began to rearm. The Rhineland was remilitarised. Germany later annexed Austria in 1938, the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia and Memel from Lithuania in 1939. Germany then invaded the rest of Czechoslovakia in 1939, creating the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and Slovakia as a country.

On August 23, 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which contained a secret protocol dividing eastern Europe into spheres of influence.[4] Germany's invasion of its part of Poland under the Pact eight days later[5] led to the subsequent beginning of World War II. By 1941, Germany occupied most of Europe and its military forces were fighting the Soviet Union, nearly capturing its capital of Moscow. However, crushing defeats at the Battle of Stalingrad and the Battle of Kursk devastated the German armed forces. This combined with Western Allied landings in France and Italy led to a three-front war which depleted Germany's armed forces resulting in Germany's defeat in 1945.

Japan

Japan was the principal Axis power in Asia and the Pacific. The Empire of Japan, commonly referred to as Imperial Japan, was a constitutional monarchy ruled by Emperor Shōwa. The constitution prescribed that "The Emperor is the head of the Empire, combining in Himself the rights of sovereignty, and exercises them, according to the provisions of the present Constitution" (article 4) and that "The Emperor has the supreme command of the Army and the Navy" (article 11). Under the imperial institution were a political cabinet and Imperial General Headquarters with two chiefs of staff.

At its height, Japan's Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere included Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, large parts of China, Malaysia, French Indochina, Dutch East Indies, The Philippines, Burma, some of India, and various other Pacific Islands - specifically in the central Pacific.

As a result of the internal discord and economic downturn of the 1920s, militaristic elements set Japan on a path of expansionism. Japan had plans to establish its hegemony in Asia and thus become self-sufficient, as the Japanese home islands lacked natural resources needed for growth, by acquiring areas with abundant natural resources. Japan's expansionist policies alienated it from other countries in the League of Nations and by the mid-1930s brought it closer to Germany and Italy which both had pursued similar expansionist policies which resulted in condemnation by a number of countries. Initial steps of Japan aligning itself militarily with Germany began with the Anti-Comintern Pact, in which the two countries agreed to ally with each other to challenge any attack by the Soviet Union.

Japan's first major belligerent action was against the Chinese in 1937. The subsequent Japanese invasion and occupation of parts of China resulted in numerous atrocities against civilians such as the Nanking massacre and the Three Alls Policy. The Japanese also fought skirmishes with Soviet-Mongolian forces in Manchukuo in 1938 & 1939. Japan sought to avoid potential war with the Soviet Union by signing a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union later in 1941.

With European colonial powers focused on the war in Europe, Japan sought to acquire their colonies. In 1940 Japan responded to the collapse of France to the Germans, by occupying French Indochina. The regime of Vichy France, a de-facto ally of Germany, accepted Japan's takeover of Indochina. Allied forces did not respond with war. However, with the continuing war in China, the United States instituted in 1941 an embargo against Japan cutting off the supply of scrap metal and oil needed for its industry, trade and war effort.

In order to isolate American forces in the Philippines and American naval power, the Imperial General Headquarters ordered the Imperial Japanese Navy to attack the U.S. Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii on December 7, 1941. The Japanese forces also invaded Malaysia and Hong Kong. The Japanese initially were able to inflict a series of defeats against the Allies, however by 1943 American industrial strength was made apparent and the Japanese forces were pushed back towards the home islands. The Pacific War lasted until the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. The Soviets formally declared war in August, 1945 and engaged Japanese forces in Manchuria and northeast China.

Italy

The Kingdom of Italy was under the leadership of the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini in the name of King Victor Emmanuel III.

During World War I, Italy had entered the war against Germany and Austria-Hungary. At the end Italy made only minor gains rather than the large concessions promised by the London Pact. The London pact was nullified with the treaty of Versailles, Italian nationalists and the public saw this as an injustice and an outrage; there had been over 600,000 Italian casualties. This resentment together with internal discontent and an economic downturn allowed the Italian Fascists under Benito Mussolini to rise to power in 1922.

In the late 19th century after the reunification, a nationalist movement grew around the concept of Italia irredenta which advocated the incorporation of Italian-speaking areas under foreign rule into Italy; there was a desire to annex Italian speaking areas in Dalmatia. Italy's Fascist regime's intention was to create a "New Roman Empire" in which Italy would dominate the Mediterranean Sea. In 1935-1936, Italy invaded and annexed Ethiopia. The League of Nations protested, however no serious action was taken, though Italy faced diplomatic isolation by many countries. In 1937 Italy left the League of Nations and in the same year joined the Anti-Comintern Pact which was signed by Germany and Japan the preceding year. In March/April 1939 Italian troops invaded and annexed Albania. Germany and Italy signed the Pact of Steel on May 22.

Italy entered World War II on June 10, 1940. In September 1940 Germany, Italy and Japan signed the Tripartite Pact. By 1941, however, the Italians had suffered multiple military defeats; in Greece and against the British in Egypt. It was only through German intervention in Yugoslavia, the Balkans and North Africa that Italy managed to avert a major military collapse. By 1943 the Italian people had lost faith in Mussolini and no longer supported the war; Italy had lost its colonies, the allies had taken North Africa in May and Sicily had been invaded in July.

On July 25, 1943, King Victor Emmanuel III dismissed Mussolini, placed him under arrest, and began secret negotiations with the Allies. Italy then signed an armistice with the Allies on September 8, 1943 and later joined the Western Allies as a co-belligerent. On September 12, 1943, Mussolini was rescued by the Germans in Operation Oak and a puppet state was formed in northern Italy (see "German puppet states" below), although it exercised little real power and Italy continued as a member of the Axis Tripartite Pact in name only. This resurrected Fascist state was referred to as Repubblica di Salò or the Italian Social Republic (Repubblica Sociale Italiana/RSI).

Hungary

Hungary was ruled by Regent Admiral Miklós Horthy. Hungary was the first country apart from Germany, Italy, and Japan to adhere to the Tripartite Pact, signing the agreement on 20 November 1940.

In the late 1910s and early 1920s, political instability plagued the country until a regency was established by Miklos Horthy. Horthy, who was a Hungarian nobleman and Austro-Hungarian naval officer, became Regent in 1920. In Hungary, nationalism was strong, as was anti-Semitism, which drew Hungarian nationalists to support the Nazi regime in Germany. There was a desire by Hungarian nationalists to recover the territories lost through the Trianon Treaty. Hungary drew closer to Germany and Italy largely because of the shared desire to revise the peace settlements made after the First World War. Because of its pro-German stance, the Hungarians received favourable territorial settlements in the form of territory from German annexed Czechoslovakia in 1939 and Northern Transylvania from Romania in the Vienna Awards of 1940. During the invasion of Yugoslavia, the Hungarians permitted German troops to transit through their territory and Hungarian forces also took part in the invasion. Parts of Yugoslavia were annexed to Hungary; in response, the United Kingdom immediately broke off diplomatic relations.

Although Hungary did not participate initially in the German invasion of the Soviet Union, on 27 June Hungary declared war on the Soviet Union. Over 500,000 troops served in the Eastern Front. All five of Hungary's field armies ultimately participated in the war against the Soviet Union; the largest and the most significant contribution was made by the Second Army.

On 25 November 1941, Hungary was one of thirteen signatories to the revived Anti-Comintern Pact. Hungarian troops like their other Axis counterparts were involved in numerous actions against the Soviets. By the end of 1943, however, the Soviets had gained the upper hand while the Germans found themselves in retreat. The Hungarian Second Army was destroyed in fighting near Voronezh, on the banks of the Don River. In 1944, with Soviet troops advancing toward Hungary, Horthy attempted to reach an armistice with the allies. However, the Germans replaced the existing regime with a new one. Eventually Budapest was taken by the Soviets, after fierce fighting. A number of pro-German Hungarians retreated to Italy and Germany where they fought until the end of the war.

Romania

When war erupted in Europe in 1939, Romania was pro-British and was allied to the Poles. However following the invasion of Poland by Germany and the Soviet Union, and the German conquest of France and the low countries, Romania found itself increasingly isolated. Pro-German and pro-fascist elements began to grow.

The August 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union contained a secret protocol ceding Bessarabia, part of northern Romania, to the Soviet Union.[4] On June 28, 1940, the Soviet Union occupied and annexed Bessarabia, as well as Northern Bukovina and the Hertza region.[6] On August 30, 1940, Germany forced Romania to cede Northern Transylvania to Hungary as a result of the second Vienna Award. Southern Dobruja was also ceded to Bulgaria in September 1940. In an effort to appease the Fascist elements with the country and obtain German protection, King Carol II appointed the General Ion Antonescu as Prime Minister on September 6, 1940.

Two days later, Antonescu forced the king to abdicate and installed the king's young son Michael on the throne, then declared himself Conducător (Leader) with dictatorial powers. Under King Mihai I and the military government of Antonescu, Romania signed the Tripartite Pact on November 23, 1940. German troops entered the country in 1941 and used the country as platform for invasions of both Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. Romania was also a key supplier of resources, especially oil and grain.

Romania joined the German led invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Nearly 800,000 Romanian troops fought on the Eastern front. Areas that were annexed by the Soviets were reincorporated into Romania. By 1943, the tide began to turn and the Soviets pushed further west closer to Romania. Foreseeing the fall of Nazi Germany, Romania switched sides during King Michael's Coup on 23 August 1944. Romanian troops then fought alongside the Soviet Army until the end of war, reaching as far as Czechoslovakia and Austria.

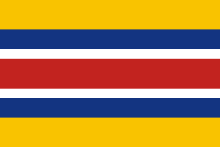

Bulgaria

Bulgaria was ruled by Тsar Boris III when the country signed the Tripartite Pact on March 1, 1941. Bulgaria had been an ally of Germany in the First World War and like Germany, sought a return of lost territory, specifically Macedonia and Aegean Thrace. During the 1930s, because of traditional right-wing elements Bulgaria drew closer to Nazi Germany. In 1940, under the terms of the Treaty of Craiova, Germany pressured Romania to return Southern Dobrudja to Bulgaria which was ceded in 1913. The promised reward for joining the axis powers was establishment of the Bulgaria within the borders defined by the Treaty of San Stefano.

Bulgaria participated in the German invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece, and annexed Vardar Banovina from Yugoslavia and eastern Greek Macedonia and Western Thrace from Greece. Bulgarian forces garrisoned in the Balkans fought various resistance movements. Despite German pressure, Bulgaria did not join the German invasion of the Soviet Union and never declared war on this country. However, despite the lack of official declarations of war by both sides, the Bulgarian Navy was involved in a number of skirmishes with the Soviet Black Sea Fleet, which attacked Bulgarian shipping.

The Bulgarian government declared war on the Western Allies. However, this turned into a disaster for the citizens of Sofia and other major Bulgarian cities, which were heavily bombed by the USAAF and RAF in 1943 and 1944. As the Red Army approached the Bulgarian border, on September 2, 1944, a coup brought to power a new government which sought peace with the Allies. However, on September 5 the Soviet Union declared war on Bulgaria and the Red Army marched into the country, meeting no resistance. During the coup d'état of 9 September 1944, a new government of the Fatherland Front took power and Bulgarian troops fought on the Allies' side throughout the rest of the war. Bulgaria kept Southern Dobrudja but lost the occupied parts of the Aegean region and Vardar Macedonia resulting in 150,000 Bulgarians being expelled from Western Thrace.

Co-belligerents

San Marino

Since 1923, San Marino was ruled by the Sammarinese Fascist Party (PFS) and was closely allied to Italy. On 17 September 1940, San Marino declared war on the United Kingdom though the UK and other Allied nations did not reciprocate.[7] San Marino also restored relations with Germany as it did not attend the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. This was done to avoid a repeat of the 1936 incident when San Marino denied a Turkish student entry because he was an enemy alien.[8]

Three days after the fall of Mussolini, PFS rule collapsed and the new government declared neutrality in the conflict. The Fascists regained power on 1 April 1944 but kept neutrality intact. On 26 June, the Royal Air Force accidentally bombed the country, killing 63. The Fascists and the Axis used this tragedy in propaganda about "Allied aggression" against a neutral country.

Retreating Axis forces occupied San Marino on 17 September but were driven out by the Allies in three days. The Allied occupation threw the Fascists out of power and San Marino declared war on Germany on 21 September.[9] The newly elected government banned the Fascists on 16 November.

Finland

Although Finland never signed the Tripartite Pact and legally (de jure) was not a part of the Axis, it was Axis-aligned in its fight against the Soviet Union.[10] The common term used in that kind of relationship is co-belligerence. Finland signed the revived Anti-Comintern Pact of November 1941.

The August 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union contained a secret protocol dividing much of eastern Europe and assigning Finland to the Soviet sphere of influence.[4][11] After unsuccessfully attempting to force territorial and other concessions on the Finns, in November 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Finland during the Winter War with the intention of establishing a communist puppet government in Finland.[12][13] The conflict threatened Germany's iron-ore supplies and offered the prospect of Allied interference in the region.[14]. Despite Finnish resistance, a peace treaty was signed in March 1940. After the war, Finland sought protection and support from the United Kingdom[15][16] and neutral Sweden,[17] but was thwarted by Soviet and German actions. This resulted in Finland being drawn closer to Germany, first with the intent of enlisting German support as a counterweight to thwart continuing Soviet pressure and later to help regain lost territories.

In the opening days of Operation Barbarossa, which marked Germany's breaking of the Pact by invading the Soviet Union, Finland permitted German planes returning from mine dropping runs over Kronstadt and Neva River to refuel at Finnish airfields before returning to bases in East Prussia. In retaliation the Soviet Union launched a major air offensive against Finnish airfields and towns, which resulted in a Finnish declaration of war against the Soviet Union on June 25, 1941. The Finnish conflict with the Soviet Union is generally referred as the Continuation War.

The main objective of Finland was to regain the territory lost to the Soviet Union in the Winter War. However, on July 10, 1941, Field Marshal Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim issued an Order of the Day which contained a formulation that was understood internationally as a Finnish territorial interest in Russian Karelia.

Diplomatic relations between the United Kingdom and Finland were severed on August 1, 1941, after the British bombed German forces in the Finnish city of Petsamo. The United Kingdom repeatedly called on Finland to cease its offensive against the Soviet Union, and on December 6, 1941, declared war on Finland, although no other military operations followed. War was never declared between Finland and the United States, though relations were severed between the two countries in 1944 as a result of the Ryti-Ribbentrop Agreement.

Finland maintained command of its armed forces and pursued its war objectives independently of Germany. Finland refused German requests to participate in the Siege of Leningrad, and also granted asylum to Jews, while Jewish soldiers continued to serve in her army.

The relationship between Finland and Germany more closely resembled an alliance during the six weeks of the Ryti-Ribbentrop Agreement, which was presented as a German condition for help with munitions and air support, as the Soviet offensive coordinated with D-Day threatened Finland with complete occupation. The agreement, signed by President Risto Ryti, but never ratified by the Finnish Parliament, bound Finland not to seek a separate peace.

After Soviet offensives were fought to a standstill, Ryti's successor as president, Marshall Mannerheim, dismissed the agreement and opened secret negotiations with the Soviets, which resulted a ceasefire on September 4 and the Moscow Armistice on September 19, 1944. Under the terms of the armistice, Finland was obligated to expel German troops from Finnish territory, which resulted in the Lapland War. In 1947, Finland signed a peace treaty with the Allied powers.

Iraq

Iraq was briefly a co-belligerent of the Axis, fighting the United Kingdom in the Anglo-Iraqi War of May, 1941.

Anti-British sentiments were widespread in Iraq prior to 1941. Seizing power on April 1, 1941, the nationalist government of Iraqi Prime Minister Rashid Ali repudiated the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1930 and demanded that the British abandon their military bases and withdraw from the country. Ali sought support from Germany and Italy in expelling British forces from Iraq.

In early May 1941, Mohammad Amin al-Husayni, the Mufti of Jerusalem and associate of Ali, declared "holy war" against the British and called on Arabs throughout the Middle East to rise up against British rule. On May 25, 1941, the Germans stepped up offensive operations.

Hitler issued Order 30,

"The Arab Freedom Movement in the Middle East is our natural ally against England. In this connection special importance is attached to the liberation of Iraq... I have therefore decided to move forward in the Middle East by supporting Iraq."

Hostilities between the Iraqi and British forces began on May 2, 1941, with heavy fighting at the RAF air base in Habbaniya. The Germans and Italians dispatched aircraft and aircrew to Iraq utilizing Vichy French bases in Syria, which would later invoke fighting between Allied and Vichy French forces in Syria.

The Germans planned to coordinate a combined German-Italian offensive against the British in Egypt, Palestine and Iraq. Iraqi military resistance, however, ended by May 31, 1941. Rashid Ali and the Mufti of Jerusalem fled to Iran, then Turkey, Italy and finally Germany where Ali was welcomed by Hitler as head of the Iraqi government-in-exile in Berlin. In propaganda broadcasts from Berlin, the Mufti continued to call on Arabs to rise up against the British and aid German and Italian forces. He also helped recruit Muslim volunteers in the Balkans for the Waffen SS.

Thailand

Thailand became a formal ally of Japan from January 25, 1942.

In the immediate aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces invaded Thailand's territory on the morning of December 8, 1941. Only hours after the invasion, the then prime minister Field Marshal Phibunsongkhram, ordered the cessation of resistance against the Japanese. On December 21, 1941, a military alliance with Japan was signed and Thailand declared war on Britain and the United States. The Thai ambassador to the United States, Mom Rajawongse Seni Pramoj did not deliver his copy of the declaration of war, so although the British reciprocated by declaring war on Thailand and consequently considered it a hostile country, the United States did not.

On May 10, 1942, the Thai Phayap Army entered Burma's Shan State, at one time in the past the area had been part of the Ayutthaya Kingdom. The boundary between the Japanese and Thai operations was generally the Salween. However, the area south of the Shan States known as Karenni States, the homeland of the Karens, was specifically retained under Japanese control. Three Thai infantry and one cavalry division, spearheaded by armoured reconnaissance groups and supported by the air force engaged the retreating Chinese 93rd Division. Kengtung, the main objective, was captured on May 27. Renewed offensives in June and November evicted the Chinese into Yunnan.[18] The area containing the Shan States and Kengtung was annexed by Thailand in 1942. After the war, in 1946, the areas were ceded back to Burma.

The Free Thai Movement ("Seri Thai") was established during these first few months, parallel Free Thai organisations were also established in the United Kingdom and inside Thailand. Queen Ramphaiphanni was the nominal head of the British-based organisation, and Pridi Phanomyong, the regent, headed its largest contingent, which was operating within the country. Aided by elements of the military, secret airfields and training camps were established while OSS and Force 136 agents fluidly slipped in and out of the country.

As the war dragged on, the Thai population came to resent the Japanese presence. In June 1944, Phibun was overthrown in a coup d'état. The new civilian government under Khuang Aphaiwong attempted to aid the resistance while at the same time maintaining cordial relations with the Japanese. After the war, U.S. influence prevented Thailand from being treated as an Axis country, but the British demanded three million tons of rice as reparations and the return of areas annexed from the colony of Malaya during the war. Thailand also returned the portions of British Burma and French Indochina that had been annexed. Phibun and a number of his associates were put on trial on charges of having committed war crimes and of collaborating with the Axis powers. However, the charges were dropped due to intense public pressure. Public opinion was favourable to Phibun, since he was thought to have done his best to protect Thai interests.

Non-belligerents

Yugoslavia

On 25 March 1941, fearing that Yugoslavia would be invaded otherwise, pro-Allied Prince Paul signed the Tripartite Pact with significant reservations. Unlike other Axis powers, Yugoslavia was not obligated to provide military assistance, nor to provide its territory for Axis to move military forces during the war.

Two days after signing the alliance in 1941, after demonstrations in the streets, Prince Paul was removed from office by a coup d'état. 17-year-old Prince Peter was proclaimed to be of age, he was not crowned nor anointed (a custom of the Serbian Orthodox Church). The new Yugoslavian government under King Peter II, still fearful of invasion, attempted to indicate that it would remain bound by the Tripartite Pact. But German dictator Adolf Hitler suspected that the British were behind the coup against Prince Paul and vowed to invade the country.

The German invasion began on 6 April 1941. Yugoslavia was a country concocted by the Versailles World Order as multi-ethnic state from its creation and was heavily dominated by peoples of the Eastern Orthodox religion. It also had unresolved questions of national identity so even the resistance to Nazi occupation wasn't united until major resistance groups like the partisans and Chetniks began forming and making offenses in the Balkans. Resistance crumbled in less than two weeks and an unconditional surrender was signed in Belgrade on 17 April. By this time, King Peter II and much of the Yugoslavian government had already fled, taking the national gold reserves, foreign currency reserves and other possessions.

While the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was no longer capable of being a member of the Axis, several Axis-aligned puppet states emerged after the kingdom was dissolved. Local governments were set up in Serbia, Croatia, and Montenegro. The remainder of Yugoslavia was divided among the other Axis powers. Germany annexed parts of Drava Banovina. Italy annexed south-western Drava Banovina, coastal parts of Croatia (Dalmatia and the islands), and attached Kosovo to Albania (occupied since 1939). Hungary annexed several border territories of Vojvodina. Bulgaria annexed Macedonia and parts of southern Serbia. Because of the dismemberment of its territory, Yugoslavia developed a massive resistance movement primarily led by the Serbs, and was the only other country in Eastern Europe, (aside from the Soviet Union) to liberate itself.

Japanese puppet states

The Empire of Japan created a number of puppet states in the areas occupied by its military, beginning with the creation of Manchukuo in 1932. These puppet states achieved varying degrees of international recognition.

Manchukuo (Manchuria)

Manchukuo was a Japanese puppet state in Manchuria, the northeast region of China. It was nominally ruled by Puyi, the last emperor of the Qing Dynasty, but in fact controlled by the Japanese military, in particular the Kwantung Army. While Manchukuo ostensibly meant a state for ethnic Manchus, the region had a Han Chinese majority.

Following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the independence of Manchukuo was proclaimed on February 18, 1932, with Puyi as "Head of State." He was proclaimed the Emperor of Manchukuo a year later. Twenty three of the League of Nations' eighty members recognised the new Manchu nation, but the League itself declared in 1934 that Manchuria lawfully remained a part of China. This precipitated Japanese withdrawal from the League. Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union were among the major powers who recognised Manchukuo. Other countries who recognised the State were the Dominican Republic, Costa Rica, El Salvador, and the Vatican. Manchukuo was also recognised by the other Japanese allies and puppet states, including Mengjiang, the Burmese government of Ba Maw, Thailand, the Wang Jingwei regime, and the Indian government of Subhas Chandra Bose. The Manchukuoan state ceased to exist after the Soviet invasion of Manchuria in 1945.

Mengjiang (Inner Mongolia)

Mengjiang (alternatively spelled Mengchiang) was a Japanese puppet state in Inner Mongolia. It was nominally ruled by Prince Demchugdongrub, a Mongol nobleman descended from Genghis Khan, but was in fact controlled by the Japanese military. Mengjiang's independence was proclaimed on February 18, 1936, following the Japanese occupation of the region.

The Inner Mongolians had several grievances against the central Chinese government in Nanking, with the most important one being the policy of allowing unlimited migration of Han Chinese to this vast region of open plains and desert. Several of the young princes of Inner Mongolia began to agitate for greater freedom from the central government, and it was through these men that Japanese saw their best chance of exploiting Pan-Mongol nationalism and eventually seizing control of Outer Mongolia from the Soviet Union.

Japan created Mengjiang to exploit tensions between ethnic Mongolians and the central government of China which in theory ruled Inner Mongolia. The Japanese hoped to use pan-Mongolism to create a Mongolian ally in Asia and eventually conquer all of Mongolia from the Soviet Union.

When the various puppet governments of China were unified under the Wang Jingwei government in March 1940, Mengjiang retained its separate identity as an autonomous federation. Although under the firm control of the Japanese Imperial Army which occupied its territory, Prince Demchugdongrub had his own army that was, in theory, independent.

Mengjiang vanished in 1945 following Japan's defeat ending World War II and the invasion of Soviet and Red Mongol Armies. As the huge Soviet forces advanced into Inner Mongolia, they met limited resistance from small detachments of Mongolian cavalry, which, like the rest of the army, were quickly brushed aside.

Wang Jingwei Government

A short-lived state was founded on March 29, 1940 by Wang Jingwei, who became Head of State of this Japanese supported collaborationist government based in Nanking.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Japan advanced from its bases in Manchuria to occupy much of East and Central China. Several Japanese puppet states were organised in areas occupied by the Japanese Army, including the Provisional Government of the Republic of China at Peking which was formed in 1937 and the Reformed Government of the Republic of China at Nanking which was formed in 1938. These governments were merged into the Reorganised Government of the Republic of China at Nanking in 1940. The government (known as the Wang Jingwei Government) was to be run along the same lines as the Nationalist regime and adopted symbols of the latter.

The Nanking Government had no real power, and its main role was to act as a propaganda tool for the Japanese. The Nanking Government concluded agreements with Japan and Manchukuo, authorising Japanese occupation of China and recognising the independence of Manchukuo under Japanese protection. The Nanking Government signed the Anti-Comintern Pact of 1941 and declared war on the United States and the United Kingdom on January 9, 1943.

The government had a strained relationship with the Japanese from the beginning. Wang's insistence on his regime being the true Nationalist government of China and in replicating all the symbols of the Kuomintang (KMT) led to frequent conflicts with the Japanese, the most prominent being the issue of the regime's flag, which was identical to that of the Republic of China.

The worsening situation for Japan from 1943 onwards meant that the Nanking Army was given a more substantial role in the defence of occupied China than the Japanese had initially envisaged. The army was almost continuously employed against the communist New Fourth Army.

Wang Jingwei died in a Nagoya hospital on November 10, 1944, and was succeeded by his deputy Chen Gongbo. Chen had little influence and the real power behind the regime was Zhou Fohai, the mayor of Shanghai. Wang's death dispelled what little legitimacy the regime had. The state stuttered on for another year and continued the display and show of a fascist regime.

On September 9, 1945, following the defeat of Japan, the area was surrendered to General He Yingqin, a nationalist general loyal to Chiang Kai-shek. The Nanking Army generals quickly declared their alliance to the Generalissimo, and were subsequently ordered to resist Communist attempts to fill the vacuum left by the Japanese surrender. Chen Gongbo was tried and executed in 1946.

Burma (Ba Maw regime)

The Japanese Army seized control of Burma from the United Kingdom during 1942. A Japanese puppet state in Burma was then formed on August 1 under the Burmese nationalist leader Ba Maw. The Ba Maw regime established the Burma Defence Army (later renamed the Burma National Army), which was commanded by Aung San.

Philippines (Second Republic)

The Japanese established a puppet state in the Philippine Islands in 1942. In 1943, the Philippine National Assembly declared the Philippines an independent republic and elected Jose P. Laurel as President of the Second Republic of the Philippines. There was never widespread support for the state, largely because of the anti-Japanese attitude of the people. The Second Philippine Republic ended with the Japanese surrender. Laurel was arrested and charged with treason by the US government, but was granted amnesty and continued being involved in politics, ultimately winning a seat in the Philippine Senate.

India (Provisional Government of Free India)

The Provisional Government of Free India was a shadow government led by Subhas Chandra Bose, an Indian nationalist who rejected Gandhi's nonviolent methods for achieving independence. Its authority existed only in those parts of India which came under Japanese control.

One of the most prominent leaders of the Indian independence movement of the time and former president of the Indian National Congress, Bose was arrested by British authorities at the outset of the Second World War. In January 1941 he escaped from house arrest, eventually reaching Germany and then in 1942 to Japan where he formed the Indian National Army, made up largely from Indian prisoners of war.

Bose and A.M. Sahay, another local leader, received ideological support from Mitsuru Toyama, chief of the Dark Ocean Society along with Japanese Army advisers.[19] Other Indian thinkers in favour of the Axis cause were Asit Krishna Mukherji, a friend of Bose and his wife Savitri Devi, a French writer who admired Hitler.[20] Bose was helped by Rash Behari Bose, founder of the Indian Independence League in Japan. Bose declared India's independence on October 21, 1943. The Japanese Army assigned to the Indian National Army a number of military advisors, among them Hideo Iwakuro and Saburo Isoda.

The provisional capital was located at Port Blair on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, these islands fallen to the Japanese. The government would last two more years until August 18, 1945, when it officially became defunct. During its existence it received recognition from nine governments: Germany, Japan, Italy, Croatia, Manchukuo, China (under the Nanking Government of Wang Jingwei), Thailand, Burma (under the regime of Burmese nationalist leader Ba Maw), and the Philippines under de facto (and later de jure) president José Laurel.

Vietnam (Empire of Vietnam)

The Empire of Vietnam was a short-lived Japanese puppet state that lasted from March 11 to August 23, 1945.

When the Japanese seized control of French Indochina, they allowed Vichy French administrators to remain in nominal control. This ruling ended on March 9, 1945 when the Japanese officially took control of the government. Soon after, Emperor Bảo Đại voided the 1884 treaty with France and Trần Trọng Kim, a historian, became prime minister.

Despite the state's short existence, it suffered through a famine (see Vietnamese Famine of 1945) as well as succeeding in replacing French-speaking schools with Vietnamese language schools taught by Vietnamese scholars.

Cambodia

The Kingdom of Cambodia was a short-lived Japanese puppet state that lasted from March 9, 1945 to April 15, 1945.

In mid-1941, the Japanese entered Cambodia, but allowed Vichy French officials to remain in administrative posts. The Japanese calls of an "Asia for the Asiatics" won over many Cambodian nationalists, despite Tokyo's policy of keeping the colonial government in nominal control.

This policy changed during the last months of the war. The Japanese wanted to gain local support, so they dissolved French colonial rule and pressured Cambodia to declare its independence within the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Four days later, King Sihanouk declared Kampuchea (the original Khmer pronunciation of Cambodia) independent. Co-editor of the Nagaravatta, Son Ngoc Thanh, returned from Tokyo in May and was appointed foreign minister.

On the date of Japanese surrender, a new government was proclaimed with Son Ngoc Thah as prime minister. However, in October, when the Allies occupied Phnom Penh, Son Ngoc Thanh was arrested for collaborating with the Japanese and was exiled to France. Some of his supporters went to north-western Cambodia, which had been under Thai control since the French-Thai War of 1940, where they banded together as one faction in the Khmer Issarak movement, originally formed with Thai encouragement in the 1940s.

Laos

Fears of Thai irredentism led to the formation of the first Lao nationalist organization, the Movement for National Renovation, in January 1941, led by Prince Phetxarāt and supported by local French officials, though not by the Vichy authorities in Hanoi. This group wrote the current Lao national anthem and designed the current Lao flag, while paradoxically pledging support for France. The country declared its independence in 1945.

There matters rested until the liberation of France in 1944, bringing Charles de Gaulle to power. This meant the end of the alliance between Japan and the Vichy French administration in Indochina. The Japanese had no intention of allowing the Gaullists to take over, and in late 1944 they staged a military coup in Hanoi. Some French units fled over the mountains to Laos, pursued by the Japanese, who occupied Viang Chan in March 1945 and Luang Phrabāng in April. King Sīsavāngvong was detained by the Japanese, but his son Crown Prince Savāngvatthanā called on all Lao to assist the French, and many Lao died fighting against the Japanese occupiers.

Prince Phetxarāt, however, opposed this position, and thought that Lao independence could be gained by siding with the Japanese, who made him Prime Minister of Luang Phrabāng, though not of Laos as a whole. In practice the country was in chaos and Phetxarāt's government had no real authority. Another Lao group, the Lao Sēri (Free Lao), received unofficial support from the Free Thai movement in the Isan region.

Italian puppet states

Montenegro

Sekula Drljević and the core of the Montenegrin Federalist Party formed the Provisional Administrative Committee of Montenegro on July 12, 1941, and proclaimed on the Saint Peter's Congress the "Kingdom of Montenegro" under protectorate of the Fascist Kingdom of Italy. The country served Italy as part of its goal fragmenting the former Kingdom of Yugoslavia, expanding the Italian Empire throughout the Adriatic Sea. The country was mostly caught by the rebellion of the Yugoslav Army in the Fatherland and Drljevic was already in October 1941 expelled from Montenegro which became under direct Italian control with the remainder of the Montenegrin collaborators. In 1943 with the Italian capitulation, Montenegro became a direct sector of occupation of Nazi Germany.

In 1944, Drljević formed a pro-Ustaše Montenegrin State Council in exile based in the Independent State of Croatia with the aims of restoring rule over Montenegro. It subsequently formed a Montenegrin People's Army out of various Montenegrin nationalist troops. By then the Partisans already liberated most of Montenegro, which became a federal state of the new Democratic Federal Yugoslavia. Montenegro endured intense air bombing by the Allied air forces in 1944.

German puppet states

Slovakia (Tiso regime)

The Slovak Republic under President Josef Tiso signed the Tripartite Pact on November 24, 1940.

Slovakia had been closely aligned with Germany almost immediately from its declaration of independence from Czechoslovakia on March 14, 1939. Slovakia entered into a treaty of protection with Germany on March 23, 1939.

Slovak troops joined the German invasion of Poland, having interest in Spiš and Orava. Those two regions (alongside with Cieszyn Silesia) were divided and disputed between Poland and Czechoslovakia since 1918, until the Poles fully annexed them following the Munich agreement. After the September Campaign, Slovakia reclaimed control of those territories.

Slovakia declared war on the Soviet Union in 1941 and signed the revived Anti-Comintern Pact of 1941. Slovak troops fought on Germany's Eastern Front, with Slovakia furnishing Germany with two divisions totalling 20,000 men. Slovakia declared war on the United Kingdom and the United States of America in 1942.

Slovakia was spared German military occupation until the Slovak National Uprising, which began on August 29, 1944, and was almost immediately crushed by the Waffen SS and Slovak troops loyal to Josef Tiso, the Catholic priest-turned-dictator of Slovakia.

After the war, Tiso was executed and Slovakia was rejoined with Czechoslovakia. The border with Poland was shifted back to the pre-war state. Slovakia and the Czech Republic finally separated into independent states in 1993.

Serbia (Nedić regime)

In April 1941, Germany invaded and occupied Yugoslavia. On April 30, a pro-German Serbian administration was formed under Milan Aćimović.[21] In 1941, after the invasion of the Soviet Union, a guerilla campaign against the Germans and Italians was launched by the communist Partisans under Josip Broz Tito. The uprising became a serious concern for the Germans as most of their forces were deployed to Russia; only three divisions of which were in the country. On August 13, 546 Serbs, including many of the country's most prominent and influential leaders, issued an appeal to the Serbian nation which called for loyalty to the Nazis and condemned the Partisan resistance as unpatriotic.[22] Two weeks after the appeal, with the Partisan insurgency beginning to gain momentum, seventy five prominent Serbs convened a meeting in Belgrade where it was decided to form a Government of National Salvation under Serbian General Milan Nedić to replace the existing Serbian administration.[23] On August 29, the German authorities installed General Nedić and his government in power.[23] Nedić would serve as Prime Minister, while the former Yugoslavian Regent, Prince Paul, would be recognized as its head of state. The Germans were short of police and military forces in Serbia, as a result the Germans came to rely on armed Serbian formations to maintain order[24] By October, 1941, Serbian forces under German supervision became increasingly effective against the resistance.[25] These Serbian formations were German armed and equipped.

Nedić's forces included the Serbian State Guards and the Serbian Volunteer Corps, which were initially largely members of the fascist Yugoslav National Movement "Zbor" (Jugoslovenski narodni pokret "Zbor", or ZBOR) party. Some of these formations wore the uniform of the Royal Yugoslav Army as well as helmets and uniforms purchased from Italy, while others from Germany.[26] These forces were involved, either directly or indirectly, in the mass killings of not only Croats, Muslims and Jews but also Serbs who sided with any anti-German resistance or were suspects of being a member of such.[27] After the war, the Serbian involvement in many of these events and the issue of Serbian collaboration were subject to historical revisionism.[28]

The apparatus of the German occupying forces in Serbia was supposed to maintain order and peace in this region and to exploit its industrial and other riches, necessary for the Germany war economy. But, however well organised, it could have not realized its plans successfully if the old apparatus of state power, the organs of state administration, the gendarmes, and the Police had not been at its service.[29]

Several concentration camps were formed in Serbia and at the 1942 Anti-Freemason Exhibition in Belgrade the city was pronounced to be free of Jews (Judenfrei). On 1 April 1942, a Serbian Gestapo was formed.

Italy (Salò regime)

Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini formed the Italian Social Republic (Repubblica Sociale Italiana in Italian) on September 23, 1943, succeeding the Kingdom of Italy as a member of the Axis.

Mussolini had been removed from office and arrested by King Victor Emmanuel III on July 25, 1943. The King publicly reaffirmed his loyalty to Germany, but authorized secret armistice negotiations with the Allies. In a spectacular raid led by German paratrooper Otto Skorzeny, Mussolini was rescued from arrest.

Once safely ensconced in German occupied Salò, Mussolini declared that the King was deposed, that Italy was a republic and that he was the new president. He functioned as a German puppet for the duration of the war.

With the creation of the German-backed puppet Italian Social Republic, about 20% of Italy's Jews were killed, despite the Fascist government's initial refusal to deport Jews to Nazi death camps[citation needed].

Albania (under German control)

After Benito Mussolini was overthrown by his own Italian Grand Council, a void of power opened up in Albania. The Italian occupying forces could do nothing as the National Liberation Movement (NLM) took control of the south and National Front (Balli Kombëtar) took control of the north. Albanians in the Italian army scurried to join the guerrilla forces. In September 1943, the guerrillas moved to take the capital of Tirana, but before they could, German paratroopers dropped into the city. Soon after a long fight, German High Command announced that they would recognize the independence of a neutral Albania and organized an Albanian government, police, and military. The country retained the official name the Albanian Kingdom and existed in borders set by Italy in 1941. Since King Zog I was in absentia, a High Council of Regency was created to carry out the functions of a head of state, while the government was headed mainly by Albanian conservative politicians. The Germans did not exert heavy control over Albania's administration. Instead, they attempted to gain popular appeal by giving the Albanians want they wanted. Albania is unique in that it is the only European country occupied by the Axis powers that ended World War II with a larger Jewish population than before the War.[30] Given their autonomy, the Albanian government refused to hand over their Jewish population. Instead they provided the Jewish families with forged documents and helped them disperse in the Albanian population.[31][32] However, the Axis powers did have success in cooperating with some Balli Kombëtar units in suppressing the communists. In addition, several Balli Kombëtar leaders held positions in the regime. Albania was completely liberated on November 28, 1944.

Hungary (Szálasi regime)

After relations between Germany and the regency of Miklos Horthy collapsed in Hungary in 1944, Horthy was forced to abdicate after German armed forces held his son hostage. Following Horthy's abdication, Hungary was politically reorganized into a totalitarian fascist country called the Hungarian State in December 1944 led by Ferenc Szálasi who had been Prime Minister of Hungary since October 1944 and was leader of the anti-Semitic fascist Arrow Cross Party. In power, his government was a Quisling regime with little authority other than to obey Germany's orders. Also, days after its inception, the capital of Budapest was surrounded by the Soviet Red Army. German and fascist Hungarian forces tried in vain to hold off the Soviet advance but failed. In March 1945, Szálasi fled Hungary for Germany to run the state in exile until the surrender of Germany in May 1945.

Vardar Macedonia

Ivan Mihailov, leader of the IMRO, wanted to solve the Macedonian Question by creating a pro-Bulgarian Macedonian nation. The Germans kept him on hold just in case relations with Bulgaria went awry. That problem began to take form on August 23, 1944, when Romania left the Axis and subsequently declared on Germany. This opened up the way to Bulgaria for the Soviet Union. Thus the Soviets declared war on Bulgaria on September 5. While these events were taking place, Mihailov came out of hiding in the Independent State of Croatia and traveled to re-occupied Skopje. The Germans gave Mihailov the green light to create his envisioned Macedonian state. To give the state legitimacy, negotiations were made with the Bulgarian government. Contacts was made with Hristo Tatarchev in Resen, who offered Mihailov the Presidency of his state. Despite their efforts, Bulgaria switched sides on September 8, and on the 9th the Fatherland Front staged a coup and deposed the monarchy. Mihailov then refused the leadership and fled to Italy. Spiro Kitanchev took Mihailov's place and became Premier of Macedonia. He cooperated with the old, pro-Bulgarian authorities, the Wehrmacht, the Bulgarian Army and the Yugoslav Partisans from the remainder of September to October. In the middle of November, the communists won control over Vardar Macedonia.[4]

Joint German-Italian puppet states

Independent State of Croatia

On 10 April 1941, the Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, or NDH) was declared to be a member of the Axis, co-signing the Tripartite Pact. The NDH remained a member of the Axis until the end of Second World War, its forces fighting for Germany even after NDH had been overrun by Yugoslav Partisans. On 24 April 1941, Ante Pavelić, a Croatian nationalist and one of the founders of the Croatian Uprising (Ustaše) Movement, was proclaimed Leader (Poglavnik) of the new state.

The Ustaše was actively supported by the Fascist regime of Benito Mussolini in Italy which gave the movement training grounds to prepare for war against Yugoslavia as well as accepting Pavelić as an exile and allowed him to reside in Rome. Italy intended to use the movement to destroy Yugoslavia, which would allow Italy to expand its power through the Adriatic Sea. In Germany, the idea of creating any Slavic puppet state was not welcomed by Hitler who saw all Slavs, including Croats as racially inferior. Also Hitler did not want to engage in a war in the Balkans until the Soviet Union was defeated. But the Italian occupation of Greece was performing badly, Mussolini wanted Germany to invade Yugoslavia to save the Italian forces in Greece. Hitler reluctantly submitted and Yugoslavia was invaded, and the Italian agenda to set up a puppet Croatian state was achieved with the creation of the Independent State of Croatia. Relations between Germany and Croatia would improve as the Ustaše proved effective at violently repressing Serb Chetniks and the communist Yugoslav Partisans of Josip Broz Tito.

Pavelić led a Croatian delegation to Rome and offered the crown of Croatia to an Italian prince of the House of Savoy, who was crowned Tomislav II, King of Croatia, Prince of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Voivode of Dalmatia, Tuzla and Knin, Prince of Cisterna and of Belriguardo, Marquess of Voghera, and Count of Ponderano. The next day, Pavelić signed the Contracts of Rome with Mussolini, ceding Dalmatia to Italy and fixing the permanent borders between Croatia and Italy. Furthermore, Italian armed forces were allowed to control all of Croatia's coastline, effectively giving Italy total control of the Adriatic Sea coastline.

Its ruling ultra-nationalist Ustaše movement utilized the motive that Croatians had been oppressed by the Serb-dominated Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and that Croatians deserved to have an independent nation after years of domination by foreign empires, to draw support to their radical agenda. The Ustaše perceived Serbs to be racially inferior to Croats and saw them as infiltrators who were occupying Croatian lands, and saw the extermination of Serbs as necessary to racially purify Croatia.

While in Yugoslavia, many Croatian nationalists violently opposed the Serb-dominated Yugoslav monarchy and assassinated Yugoslavia's King Alexander together with Macedonian VMRO organization. The regime enjoyed support amongst radical Croatian nationalists. Ustashe forces fought against Serbian Chetnik and communist Yugoslav Partisan guerrillas throughout the war. Regular forces Croatian Home Guard (domobran) usually fought against Serbian Chetnik and often joined or surrendered with weapons to antifascist Partisans.

Upon coming to power, Pavelić formed the Croatian Home Guard (Hrvatsko domobranstvo) as the official military force of Croatia. Originally authorized at 16,000 men, it grew to a peak fighting force of 130,000. The Croatian Home Guard included a small air force and navy, although its navy was restricted in size by the Contracts of Rome. In addition to the Croatian Home Guard, Pavelić also commanded the Ustaše militia. Some Croats also volunteered for the German Waffen SS.

The Ustaše government declared war on the Soviet Union, signed the Anti-Comintern Pact of 1941 and sent troops to Germany's Eastern Front. Ustaše militia garrisoned the Balkans, battling the Partisans.

During the time of its existence, the Ustaše government applied racial laws on Serbs, Jews and Romas, and after June 1941 deported them to the Jasenovac concentration camp (or to camps in Poland). The exact number of victims of the Ustaše regime is uncertain due to the destruction of documents and varying numbers given by various historians vying for political clout. The estimates of the total number of victims in Jasenovac is from between 56,000 and 97,000 [33] to 700,000 or more. The racial laws were enforced by the Ustaše militia.

Although Ustaše had some support in all parts of Croatia, their wide popular support was limited to the traditionally most strongly nationalistic regions.

Greece

Following the German invasion of Greece and the flight of the Greek government to Crete and then Egypt, the Hellenic State was formed in May 1941 as a puppet state of both Italy and Germany. Initially, Italy had wished to annex Greece, but pressure from Germany to avoid civil unrest such as occurred in Bulgarian-annexed areas, resulted in Italy accepting to create a puppet regime with the support of Germany. Italy had been assured by Hitler of "prepoderanza" in Greece and most of the country was held by Italian forces, but strategic locations (Central Macedonia, the islands of the northeastern Aegean, most of Crete and parts of Attica) were held by the Germans, who in addition seized most of the country's economic assets, and effectively controlled the collaborationist government. The puppet regime never commanded much real authority, neither did it gain the allegiance of the people, although it was somewhat successful in preventing secessionist movements like the "Principality of Pindus" (see below) from establishing themselves. By mid-1943, the Greek Resistance had liberated large parts of the mountainous interior ("Free Greece"), setting up a separate administration there. After the Italian armistice, the Italian occupation zone was taken over by the German armed forces, who remained in charge of the country until their withdrawal in autumn 1944. In some Aegean islands however, German garrisons were left behind, and surrendered only after the end of the war.

Pindus and Macedonia

The Principality of Pindus and the Voivodship of Macedonia were Italian-sponsored attempts at forming client states in the regions of northern Greece (parts of Epirus, Thessaly and West Macedonia) inhabited by ethnic Aromanians and Slavic Macedonians.[34]

Axis collaborator states

France (Vichy regime)

France and its colonial empire, under the so-called Vichy regime of Marshal Pétain, collaborated with the Axis from 1940 until 1944 when the regime was dissolved.

Pétain became the last Prime Minister of the French Third Republic on June 16, 1940 as the battle of France following the German invasion army entering Paris on June 14. Pétain sued for peace with Germany and six days later, on June 22, 1940, his government concluded an armistice with Hitler. Under the terms of the agreement, Germany occupied approximately two thirds of metropolitan France, including Paris. Pétain was permitted to keep an "armistice army" of 100,000 men within the unoccupied southern zone. This number included neither the army based in French colonial empire nor the French fleet. In French North Africa and French Equatorial Africa, the Vichy were permitted to maintain 127,000 men under arms after the colony of Gabon defected to the Free French.[35] The French also maintained substantial garrisons at the French mandated territory of Syria and Lebanon, the French colony of Madagascar and in the French Somaliland.

After the armistice, relations between the vichy French and the British quickly deteriorated. Fearful that the powerful French fleet might fall into German hands, the British launched several naval attacks, most notable of which was against the Algerian harbour of Mers el-Kebir on July 3, 1940. Though Churchill defended his controversial decisions to attack the French Fleet, the French people themselves were less accepting of these actions. German propaganda was able to trumpet these actions as an absolute betrayal of the French people by their former allies. France broke relations with the United Kingdom after the attack and considered declaring war.

On July 10, 1940, Petain was given emergency "full powers" by a majority vote of the French National Assembly. The following day approval of the new constitution by the Assembly effectively created the French State (l'État Français) replacing the French Republic with the unofficial Vichy France; for the resort town of Vichy where Petain chose to maintain his seat of government. The new government continued to be recognised as the lawful government of France by the United States until 1942. Racial laws were introduced in France and its colonies and many French Jews were deported to Germany. Albert Lebrun, last President of the Republic, did not leave the presidential office when he moved to Vizille in July 10, 1940. By April 25, 1945, during Petain's trial, Lebrun argued he thought he would be able to return to power after the fall of Germany since he had not resigned.[36]

In September 1940, Vichy France allowed Japan to occupy French Indochina, a federation of the French colonial possessions and protectorates roughly encompassing the territory of modern day Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. The Vichy regime continued to administer the colony under Japanese military occupation. French Indochina was the base for the Japanese invasions of Thailand, Malaya and Borneo. In 1945, under Japanese sponsorship, the Empire of Vietnam and the Kingdom of Cambodia were proclaimed as Japanese puppet states.

The British permitted French General Charles de Gaulle to headquarter his Free French movement in London in a largely unsuccessful effort to win over the French colonial empire. On September 26, 1940, de Gaulle led an attack by Allied forces on the Vichy port of Dakar in French West Africa. Forces loyal to Pétain fired on de Gaulle and repulsed the attack after two days of heavy fighting. Public opinion in vichy France was further outraged, and Vichy France drew closer to Germany.

Vichy France assisted Iraq in the Anglo-Iraqi War of 1941, allowing Germany and Italy to utilize air bases in the French mandate of Syria to support the Iraqi revolt against the British. Allied forces responded by attacking Syria and Lebanon in 1941. In 1942, Allied forces attacked the French colony of Madagascar.

Vichy France was staunchly anti-Communist and enthusiastically sided with Germany in its war with the Soviet Union, and also signed the Anti-Comintern Pact of 1941. Almost 7,000 volunteers joined the anti-communist Légion des Volontaires Français (LVF) from 1941 to 1944 and some 7,500 formed the Division Charlemagne, a Waffen-SS unit, from 1944 to 1945. Both the LVF and the Division Charlemagne fought on the eastern front. Hitler never accepted that France could become a full military partner,[37] and constantly prevented the buildup of Vichy's military strength.

Other than political, Vichy's collaboration with Germany essentially was industrial, with French factories providing many vehicles to the German armed forces.

In November 1942, Vichy French troops briefly but fiercely resisted the landing of Allied troops in French North Africa, but were unable to prevail. Admiral François Darlan negotiated a local ceasefire with the Allies. In response to the landings, and Vichy's inability to defend itself, German troops occupied southern France and Tunisia, a French protectorate that formed part of French North Africa. The Bey of Tunis formed a government friendly to the Germans.

In mid-1943, former Vichy authorities in North Africa came to an agreement with the Free French and setup a temporary French government in Algiers, known as the Comité Français de Libération Nationale, with De Gaulle eventually emerging as the leader. The CFLN raised new troops, and re-organized, re-trained and re-equipped the French military under Allied supervision.

However, the Vichy government continued to function in mainland France until late 1944, but had lost most of its territorial sovereignty and military assets, with the exception of the forces stationed in French Indochina.

Controversial cases

States listed in this section were not officially members of Axis, but had controversial relations with one or more Axis members at some point during the war.

Denmark

On May 31, 1939, Denmark and Germany signed a treaty of non-aggression, which did not contain any military obligations for either party.[38] On April 9, 1940, citing intended British mining of Norwegian and Danish waters as a pretext, Germany invaded both countries. King Christian X and the Danish government, worried about German bombings if they resisted occupation, accepted "protection by the Reich" in exchange for nominal independence under German military occupation. Three successive Prime Ministers, Thorvald Stauning, Vilhelm Buhl and Erik Scavenius, maintained this samarbejdspolitik ("cooperation policy") of collaborating with Germany.

- Denmark coordinated its foreign policy with Germany, extending diplomatic recognition to Axis collaborator and puppet regimes and breaking diplomatic relations with the "governments-in-exile" formed by countries occupied by Germany. Denmark broke diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and signed the Anti-Comintern Pact of 1941.[39]

- In 1941, a Danish military corps, Frikorps Danmark was created at the initiative of the SS and the Danish Nazi Party, to fight alongside the Wehrmacht on Germany's Eastern Front. The government's following statement was widely interpreted as a sanctioning of the corps.[40] Frikorps Danmark was open to members of the Danish Royal Army and those who had completed their service within the last ten years.[41] Between 4,000 and 10,000 Danish citizens joined the Frikorps Danmark, including 77 officers of the Royal Danish Army. An estimated 3,900 of these soldiers died fighting for Germany during the Second World War.

- Denmark transferred six torpedo boats to Germany in 1941, although the bulk of its navy remained under Danish command until the declaration of martial law in 1943.

- Denmark supplied agricultural and industrial products to Germany as well as loans for armaments and fortifications. The German presence in Denmark, including the construction of the Danish part of the Atlantic Wall fortifications, was paid from an account in Denmark's central bank, Nationalbanken. The Danish government had been promised that these expenses would be repaid later, but this never happened. The construction of the Atlantic Wall fortifications in Jutland cost 5 billion Danish kroner.

The Danish protectorate government lasted until August 29, 1943, when the cabinet resigned following a declaration of martial law by occupying German military officials. The Danish navy managed to scuttle 32 of its larger ships to prevent their use by Germany. Germany succeeded in seizing 14 of the larger and 50 of the smaller vessels and later to raise and refit 15 of the sunken vessels. During the scuttling of the Danish fleet, a number of vessels were ordered to attempt an escape to Swedish waters, and 13 vessels succeeded in this attempt, four of which were larger ships.[42][43] By the autumn of 1944, these ships officially formed a Danish naval flotilla in exile[44] In 1943, Swedish authorities allowed 500 Danish soldiers in Sweden to train themselves as "police troops". By the autumn of 1944, Sweden raised this number to 4,800 and recognized the entire unit as a Danish military brigade in exile.[45] Danish collaboration continued on an administrative level, with the Danish bureaucracy functioning under German command.

Active resistance to the German occupation among the populace, virtually nonexistent before 1943, increased after the declaration of martial law. The intelligence operations of the Danish resistance was described as "second to none" by Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery after the liberation of Denmark.[46]

Soviet Union

Relations between the Soviet Union and the major Axis powers were generally hostile before 1938. In the Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union gave military aid to the Second Spanish Republic, against Spanish Nationalist forces, which were assisted by Germany and Italy. However, the Nationalist forces were victorious.

In 1938 Hitler wanted to seize Czechoslovakia, a Democratic country in Eastern Europe that had an alliance with France, the USSR, and other states in Eastern Europe. Stalin's policy was to fight: "if the Czechs will fight, we shall fight alongside them".[47]. Eastern Europe applauded the Soviet resolve and Romania even offered the Red Army free passage and supplies through their country, as long as no Red Army soldiers stayed behind. The Czechs turned to France, hoping for the same resolve. In order to persuade France not to fight, Hitler began negotiations with Chamberlain, the Prime Minister of Britain. Together they pressured France to pressure the Czechs not to fight, and Hitler offered to compromise, saying that he will only take the Sudetenland. In reality Hitler used the weakened resolve to annex Czechoslovakia. To the Soviets this looked like Western betrayal, and when Hitler offered Molotov, what was the become to the Nazi-Soviet/Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Stalin ordered Molotov to sign it, fearing diplomatic isolation.

Meanwhile, In 1938 and 1939, the USSR fought and defeated Japan in two separate border wars, at Lake Khasan and Khalkhin Gol, the latter being a Major Soviet Victory.

In 1939, the Soviet Union continued negotiations with both a Britain-France contingent and Germany regarding alliances.[48][49] On August 23, 1939, the Soviet Union and Germany signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which included a secret protocol whereby the independent countries of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania were divided into spheres of interest of the parties.[4]

On September 1, barely a week after the pact had been signed, the partition of Poland commenced with the German invasion. The Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east on September 17 and on September 28 signed secret treaty with Nazi Germany on joint coordination in fight against any potential Polish resistance.[50]

Soon after that, the Soviet Union occupied Baltic countries Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania,[6][51] in addition, it annexed Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina from Romania. The Soviet Union attacked Finland on November 30, 1939 which started the Winter War.[13] Finnish defence prevented an all-out invasion, resulting in an interim peace, but Finland was forced to cede a strategically important border areas near Leningrad.

The Soviet Union supported Germany in the war effort against Western Europe through the 1939 German-Soviet Commercial Agreement and 1940 German-Soviet Commercial Agreement with exports of raw materials (phosphates, chromium and iron ore, mineral oil, grain, cotton, rubber). These and other export goods were being transported through Soviet and occupied Polish territories and allowed Germany to circumvent the British naval blockade.

In October and November 1940, the Soviet Union approached Germany about the potential of joining the Axis, with extensive discussions talking place in Berlin.[52][53] Joseph Stalin later personally countered with a separate proposal in a letter later in November that contained several secret protocols, including that "the area south of Batum and Baku in the general direction of the Persian Gulf is recognized as the center of aspirations of the Soviet Union", referring to an area approximating present day Iraq and Iran, and a Soviet claim to Bulgaria.[53][54] Hitler never returned Stalin's letter.[55][56] Shortly thereafter, Hitler issued a secret directive on the eventual attempts to invade the Soviet Union.[54][57]

Germany ended the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact by invading the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1941.[5] That resulted in the Soviet Union becoming one of the main members of Allies.

Germany then revived its Anti-Comintern Pact, enlisting many European and Asian countries in opposition to the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union and Japan remained neutral towards each other for most of the war by the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact. The Soviet Union ended the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact by invading Manchukuo on August 8, 1945, due to agreements reached at the Yalta Conference with Roosevelt and Churchill.

Spain

Generalísimo Francisco Franco's Spanish State gave moral, economic, and military assistance to the Axis powers, while nominally maintaining neutrality. Franco described Spain as a "nonbelligerent" member of the Axis and signed the Anti-Comintern Pact of 1941 with Hitler and Mussolini.

Franco had won the Spanish Civil War with the help of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy both of which were eager to establish another fascist state in Europe. Spain owed Germany over $212 million for supplies of matériel during the Spanish Civil War, and Italian combat troops had actually fought in Spain on the side of Franco's Nationalists.

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Franco immediately offered to form a unit of military volunteers to join the invasion. This was accepted by Hitler and, within two weeks, there were more than enough volunteers to form a division - the Blue Division (División Azul in Spanish) under General Agustín Muñoz Grandes.

Additionally, over 100,000 Spanish civilian workers were sent to Germany to help maintain industrial production to free able-bodied German men for military service.

Sweden

The official policy of Sweden before, during, and after World War II was neutralism . It has held this policy for more than a century, since the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

In contrast to many other neutral countries, Sweden was not directly attacked during the war. It was however subject to British and Nazi German Naval blockades, which led to problems for the supply of food and fuels. From spring 1940 to summer 1941 Sweden and Finland were surrounded by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.

This led to difficulties in maintaining the rights and duties of neutral states in the Hague Convention. Sweden violated this as German troops were allowed to travel through Swedish Territory between July 1940 to August 1943.

In spite of the fact that it was allowed by the Hague Convention, Sweden has been criticized for exportation of iron ore to Nazi Germany war industry via the Norwegian port of Narvik. Nazi German war industry dependence on Swedish iron ore shipments was the primary reason for Great Britain and their allies to launch Operation Wilfred and the Norwegian Campaign in early April 1940. By early June 1940 the Norwegian Campaign stood as a failure for the allies, and by securing access to Norwegian ports by force Nazi Germany could obtain the Swedish iron ore supply it needed for war production despite the British naval blockade.

German, Japanese and Italian World War II cooperation

German-Japanese Axis-cooperation

Germany's and Italy's declaration of war against the United States

On December 7, Japan attacked the naval bases in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. According to the stipulation of the Tripartite Pact, Nazi-Germany was required to come to the defense of her allies only if they were attacked. Since Japan had made the first move and attacked, Germany and Italy were not obliged to aid her until the United States counterattacked on December 11, after having declared war on Japan on the 8th and attacking several Japanese outposts along the Pacific. Hitler ordered the Reichstag to formally declare war on the United States along with Italy.

Hitler made a speech in the Reichstag on December 11, 1941 three days after the United States declaration of war on the Empire of Japan saying that

The fact that the Japanese Government, which has been negotiating for years with this man, has at last become tired of being mocked by him in such an unworthy way, fills us all, the German people, and all other decent people in the world, with deep satisfaction...Germany and Italy have been finally compelled, in view of this, and in loyalty to the Tri-Partite Pact, to carry on the struggle against the U.S.A. and England jointly and side by side with Japan for the defense and thus for the maintenance of the liberty and independence of their nations and empires...As a consequence of the further extension of President Roosevelt's policy, which is aimed at unrestricted world domination and dictatorship, the U.S.A. together with England have not hesitated from using any means to dispute the rights of the German, Italian and Japanese nations to the basis of their natural existence...Not only because we are the ally of Japan, but also because Germany and Italy have enough insight and strength to comprehend that, in these historic times, the existence or non-existence of the nations, is being decided perhaps forever.[58]