Therapeutic cloning

Therapeutic cloning (also known as somatic cell nuclear transfer, cell nuclear replacement, research cloning, and embryo cloning) involves taking an egg (or oocyte) from which the nucleus has been removed, and replacing that nucleus with DNA from the cell of another organism. The result is a blastocyst (an early stage embryo with about 100 cells) with almost identical DNA to the original organism.

The procedure is controversial, and this is reflected in the language used to describe the blastocyst created. Some people believe it should not be called a blastocyst or embryo, since it has not been created by fertilisation, but others maintain that since, given the right conditions, it could still grow into a fetus and eventually a child, it doesn't seem misleading to call it an embryo.

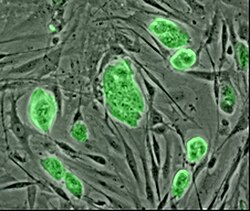

The aim of carrying out this procedure is to obtain stem cells that are genetically matched to the donor organism. For example, if a person with Parkinson's disease donated their DNA, then it should be theoretically possible to generate embryonic stem cells that could be used to treat their condition without being rejected by the patient's immune system. No such therapies presently exist, however, and the development of the technology has been delayed as governments debate whether to permit such research.

Therapeutic cloning is currently legal for research purposes in the United Kingdom, having been incorporated into the 1990 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act in 2001. In many other countries, the practice is banned, though laws are being debated and changed regularly. The United Nations voted against a Costa Rica bill to ban both reproductive cloning and therapeutic cloning on December 8, 2003.

Support for this procedure derives from its potential medical applications. Some opposition is based on the fact that the procedure destroys human embryos. Others feel that it instrumentalizes human life, or that it would be problematic to allow therapeutic cloning and still prevent reproductive cloning from occurring.