Mongol Empire

Монголын Эзэнт Гүрэн Mongolyn Ezent Guren Ikh Mongol Uls | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1206–1368 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Avarga Karakorum (1220–1271)[note 1] | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Tengriism (Shamanism), later Buddhism, Christianity and Islam | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Elective monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Great Khan | |||||||||||||||

• 1206-1227 | Genghis Khan | ||||||||||||||

• 1229-1241 | Ögedei Khan | ||||||||||||||

• 1246-1248 | Güyük Khan | ||||||||||||||

• 1251-1259 | Möngke Khan | ||||||||||||||

• 1260-1294 | Kublai Khan | ||||||||||||||

• 1333–1370 | Toghan Temur | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Kurultai | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Genghis Khan united the tribes | 1206 | ||||||||||||||

• Death of Genghis Khan | 1227 | ||||||||||||||

• Pax Mongolica | 1210-1350 | ||||||||||||||

• Fragmentation of the empire | 1260-1264 | ||||||||||||||

• Fall of Yuan Mongol Empire | 1368 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Coins (such as dirhams), Sukhe, paper money (paper currency backed by silk or silver ingots, and the Yuan's Chao) | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

The Mongol Empire (Template:Lang-mn, Mongolyn Ezent Güren or Их Mонгол улс, Ikh Mongol Uls) was an empire from the 13th and 14th century spanning from Eastern Europe across Asia. It is the largest contiguous empire in the history of the world. It emerged from the unification of Mongol and Turkic tribes in modern day Mongolia, and grew through invasions, after Genghis Khan had been proclaimed ruler of all Mongols in 1206. At its greatest extent it stretched from the Danube to the Sea of Japan(or East Sea) and from the Arctic to Camboja, covering over 24,000,000 km2 (9,266,000 sq mi),[1] 22% of the Earth's total land area, and held sway over a population of over 100 million people. It is often identified as the "Mongol World Empire" because it spanned much of Eurasia.[2][3][4][5][6][7] As a result of the empire's conquests and political and economic impact on most of the Old World, its wars with other great powers in Africa, Asia and Europe are also believed to be an ancient world war.[8][9] Under the Mongols new technologies, various commodities and ideologies were disseminated and exchanged across Eurasia.

However, the empire began to split following the succession war in 1260-1264, with the Golden Horde and the Chagatai Khanate being de facto independent and refusing to accept Kublai Khan as Khagan.[10][11] By the time of Kublai Khan's death, the Mongol Empire had already fractured into four separate khanates or empires, each pursuing its own separate interests and objectives.[12] But the Mongol Empire as a whole remained strong and united.[13] The Mongol rulers of Central Asia successfully resisted Kublai's attempt to reduce the Chagatayid and Ogedeid families to obedience. It was not until 1304, when all Mongol khans submitted to Kublai's successor, the Khagan Temür Öljeytü, that the Mongol world again acknowledged a single paramount sovereign for the first time since 1259 - and even the late Khagans' authority rested on nothing like the same foundations as that of Genghis Khan and his first three successors.[14] With the breakup of the Yuan Dynasty in 1368, the Mongol Empire finally dissolved.

Name

The Mongol Empire is translated to the Mongolian language as "Mongolyn Ezent Guren" (Монголын эзэнт гүрэн) literally meaning "Mongols' Imperial Power" and "Ikh Mongol Uls" (Их Монгол улс) which literally means "Greater Mongol Nation/State." Both of these names are used.

Political history

Formation

| History of Mongolia |

|---|

|

Before the rise of the Jin Dynasty founded by the Jurchens, the Khitan Liao Dynasty had ruled over Mongolia, Manchuria, and parts of North China since the 10th century. In 1125, the Jin Dynasty overthrew the Liao Dynasty, and attempted to gain control over former Liao territory in Mongolia. However, the Mongols under Qabul Khan, great grandfather of Temujin (Genghis Khan), pushed out the forces of the Jin Dynasty from their territory in the early 12th century. Eventually the Mongols and the Tatars began a deadly rivalry. The Golden Kings of the Jin Dynasty encouraged the Tatars in order to keep the nomads weak. There were five main powerful khanliks (tribes) in the Mongolian plateau at the time: Kereyds, Mongols, Naimans, Merkits and Tatars.

Temujin, the son of a Mongol chieftain, who suffered a difficult childhood, united the nomadic, previously ever-rivaling Mongol-Turkic tribes under his rule through political manipulation and military might. As allies, his father's friend, powerful Kereyd chieftain Wang Khan Toghoril and childhood anda (close friend) Jamukha of the Jadran clan helped him to defeat the Merkits — whose army stole his wife Borte — the Naimans and Tatars. Temujin forbade looting and raping of his enemies without permission, and he divided the spoils to Mongol warriors and their families instead of giving all to the aristocrats.[15] He thus held the title Khan—however, his uncles were also legitimate heirs to the throne. This decision brought conflict among his generals and associates and persuaded Jamukha and the Kereyds to leave Temujin. For rival aristocrats, the latter was no more than an insolent usurper. Temujin's powerful position and reputation among the Mongols and other nomads raised the fears of Kereyd elites. Virtually all his uncles, cousins and other clan chieftains had turned against him. Temujin's forces were nearly defeated in an ensuing war, but he recovered and was reinforced by tribes loyal to him. In 1203-1205, the Mongols under Temujin destroyed all the remaining rival tribes and brought them under his sway. In 1206, Temujin was crowned as the Khaghan of the Yekhe Mongol Ulus (Great Mongol Nation) at a Kurultai (general assembly/council) and assumed the title "Chingis Khan" (or more commonly known as "Genghis Khan", probably meaning Oceanic ruler or Universal ruler) instead of the old tribal titles such as Gur Khan or Tayang Khan. This event essentially marked the start of the Mongol Empire under the leadership of Genghis Khan.

Genghis Khan appointed his loyal friends as the heads of army units and households. He also divided his army into arbans (each with 10 people), zuuns (100), myangans (1000) and tumens (10,000) of decimal organization. The Kheshig or the Imperial Guard was founded and divided into day (khorchin, torghuds) and night guards (khevtuul).[16] Genghis Khan rewarded those who had been loyal to him and placed them in high positions. Most of those people were hailed from very low-rank clans. Compared to the units he gave to his loyal companions, those assigned to his own family members were quite few.[17] He proclaimed new law of the empire Ikh zasag or Yassa and codified everything related to the everyday life and political affairs of the nomads at the time. For example He forbade the hunting of animals during the breeding time, the selling of women, theft of other's properties as well as fighting between the Mongols, by his law.[18] Genghis Khan appointed his adopted brother Shigi-Khuthugh supreme judge (jarughachi) and ordered him to keep a record of blue devter. In addition to family, food and army, he also decreed religious freedom and supported domestic and international trade. Genghis Khan exempted poor people and clerics with their properties from taxation.[19] Thus, Muslims, Buddhists and Christians from Manchuria, North China, India and Persia joined Genghis Khan long before his foreign conquests. The Khaan adopted Uyghur script which would form Uyghur-Mongolian script of the empire and ordered Uyghur Tatatunga who served the khan of Naimans before to instruct his sons.[20]

He quickly came into conflict with the Jin Dynasty of the Jurchens and the Western Xia of the Tanguts in northern China. Under the provocation of the Muslim Khwarezmid Empire, he moved into Central Asia as well, devastating Transoxiana and eastern Persia, then raiding into Kievan Rus' (a predecessor state of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine) and the Caucasus. Before dying, Genghis Khan divided his empire among his sons and immediate family, but as custom made clear, it remained the joint property of the entire imperial family who, along with the Mongol aristocracy, constituted the ruling class.

The Height of World Empire

Great expansion under Ogedei Khan

At the time of Genghis khan’s death in 1227, the Mongol Empire ruled from the Pacific Ocean to the Caspian Sea – an empire twice the size of the Roman Empire and Muslim Caliphate.[21] Ogedei succeeded to the throne according to his father’s will in 1229 after his younger brother, Tolui, supervised the Empire for 2 years. To subjugate the Bashkirs, the Bulgars and other nations in the Kipchak controlled steppes, Ogedei sent troops to the area as soon as he was enthroned. They made the Bashkirs their ally.[22] In the east, his armies re-established Mongol authority in whole Manchuria, crushing the Eastern Xia regime and Water Tatars.

When the Jurchens recovered and defeated a Mongol contingent in 1230, the Great Khan personally led his army in the campaign against the Jin Dynasty. General Subotai captured Emperor Wanyan Shouxu’s capital, Kaifeng, after the Mongol envoy was killed in 1232.[23] With the assistance of the Song Dynasty, the Mongols finished off the Jin in 1234. But the belated cooperation did not advance peace between the allies when the Song troops took back their former regions lost to the Jurchens, murdering a Mongol overseer[24] in the process.[25] Meanwhile, general Chormaqan, sent by Ogedei, destroyed Jalal ud-Din Menguberdi, the last shah of Khwarizmian Empire, who had defeated Mongol forces near Isfahan in 1229, and advanced into Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia. The small kingdoms in Southern Persia voluntarily accepted Mongol supremacy.[26][27] Despite Mongol victories upon Korean armies, Ogedei’s attempt to annex the Korean peninsula met with less success. The king of Goryeo surrendered but revolted and massacred Mongol darugachis (overseers) and pro-Mongol Koreans.[28]

While Ogedei finished the construction of a new capital, Karakorum, in 1235-1238, Mongol administrations headed by Muslims and Khitans were established in North China, Turkestan and Transoxiana. In addition to building relay stations and roads, Ogedei pacified newly conquered populations and suppressed banditry or piracy. Shigi Khutugh and Yelu Chucai shared their administration during the reign of Ogedei whose authority was well respected by stronger willed relatives and generals whom he had inherited from his father. Although he became an increasingly heavy drinker after the death of Tolui, Ogedei showed heroic generosity to his subjects and decreed one out of every sheep[29] should be levied for poor people.

At the kurultai in 1234, Ogedei decided to conquer the Song Dynasty, the Kypchaks and their western allies, and the Koreans, all of whom killed Mongol envoys. Three armies commanded by his sons Kochu and Koten and the Tangut general Chagan invaded southern China. Mongol armies captured Siyang-yang, the Yangtze and Sichuan, however they couldn’t deliver the final blow to their enemy. The Song generals were able to recapture Siyang-yang from the hands of the Mongols in 1239. Kochu’s sudden death in Chinese territory forced the Mongols to be inactive in South China. Prince Koten invaded Tibet after their withdrawal.

The Mongol army under Batu Khan and his advisor Subotai overran the countries of the Bulgars, the Alans, the Kypchaks, the Bashkirs, the Mordvins, and the Chuvash and other nations of the southern Russian steppe. In 1237, they faced first Russian principality of Ryazan. After a 3 day-siege using heavy bombardment, they captured the city and massacred its inhabitants. The Mongols destroyed the army of the Grand principality of Vladimir at the Sit River and captured the Alania capital, Maghas, in 1238. By 1240, all Rus’ lands including Kiev had fallen to the Asian invaders except for a few northern cities. Mongol tumens under Chormaqan in Persia connected his invasion of Transcaucasia with the invasion of Batu and Subotai, forcing the Georgian and Armenian nobles to surrender.[30]

Batu’s relations with Güyük, Ogedei’s eldest son, and Büri, the beloved grandson of Chagatai worsened during the victory banquet in southern Russia. But they could do nothing to harm Batu’s position as long as his uncle was still alive. Meanwhile, Ogedei Khan temporarily invested Uchch, Lahore and Multan of the Delhi Sultanate and stationed a Mongol overseer in Kashmir.[31] He agreed to receive tributes from the court of Goryeo and reinforced his keshig with the Koreans through his diplomacy and military forces.[32][33][34] The court of Goryeo eventually moved their capital to Kanghwa Island.

The advance into Europe continued with Mongol invasions of Poland, Hungary and Transylvania. When the western flank of the Mongols plundered Polish cities, a European alliance consisting of the Poles, the Moravians, the Hospitallers, Teutonic Knights and the Templars assembled sufficient army to halt their advance at Liegnica. The Mongols destroyed their foes. The Hungarian army and their allies the Croatians and the Templar Knights were beaten at the banks of Sajo River on April 11, 1241. After their stunning victories over European Knights at Liegnica and Muhi, Mongol armies quickly checked the forces of Bohemia, Serbia, Babenberg Austria and the Holy Roman Empire.[35][36] When Batu’s forces reached the gate of Vienna and north Albania, he received news of Ogedei’s death in December, 1241.[37][38] As was customary in Mongol military tradition, all Genghisid princes had to attend the kurultai to elect a successor. The western Mongol army withdrew from Central Europe the next year.

Struggles for superpower

Ogedei’s widow, Toregene, took over the empire and began to persecute her husband’s Khitan and Muslim officials. The Empress gave high positions to her allies instead. She built palaces, cathedrals and social structures on an imperial scale, supporting religion and education. Toregene won over most Mongol aristocrats to support Ogedei's son, Guyuk, but Batu refused to come to the kurultai, claiming he was ill and the Mongolian climate is too harsh for him. The resulting stalemate lasted more than four years. This sudden vacuum of power is seen as the cause of the ensuing events that led to the decline of the Mongol unity. At the same time, the Mongol contingents and general Baiju of the Besud had already defeated the Anatolian Seljuks and ravaged territories of the Song Dynasty, Syria, Korea, Iraq and India.[39] When Genghis Khan’s youngest brother, Temuge, threatened the Great Khatun Toregene to seize the throne, Guyuk came to Karakorum to secure his position immediately. Batu, the ruler of the Golden Horde, eventually agreed to send his brothers and generals to the kurultai. Toregene at last arranged the kurultai in 1246. Although, Guyuk was sick and addicted to alcohol, his campaigns in Manchuria and Europe gave him the kind of stature necessary for a Khagan. His election was attended by many foreign dignitaries as well as the Mongol people. In addition to Mongol nobles and non-Mongol grandees from all parts of the Mongol Empire, subservient leaders and diplomats arrived from Georgia, Korea, China, Russia, Turkestan, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Syria, Iran, Rome and Baghdad (such as David VII Ulu, Davit VI Narin, Plano Carpini and Vladimir Yaroslav with his two sons Alexander and Andrey) came to the kurultai to show their respects and negotiate diplomacy.[40][41] Once the coronation was concluded, Guyuk limited notorious abuses of nobles and demonstrated that he would continue his father’s policy. He harshly punished his mother’s intimates for bewitching and corruption except governor Arghun the Elder. He had Temuge investigated by Orda and Mongke secretly and put him to death.[42] The Great khan replaced young Khara Hulegu, the Khan of the Chagatai Khanate, with his favorite cousin Yesü Möngke to assert his newly conferred powers. During the reign of Guyuk, Genghis Khan’s daughter Altalaun died mysteriously. There was considerable unhappiness among some members of the Golden family. Nevertheless, Batu needed to respect Guyuk and never decided major foreign affairs himself without his permission. Guyuk put David Ulu on the throne of the Georgian kingdom and decided that David Narin, Batu’s protégé, should be subordinate to him.[43] He divided the Sultanate of Rum between Izz-ad-Din Kaykawus and Rukn ad-Din Kilij Arslan, though Kaykawus disagreed with this decision.[44][45]

The Hashshashins, the former Mongol ally, whose Grand master Hasan Jalalud-Din offered his submission to Genghis Khan in 1221, angered Guyuk by murdering Mongol generals in Persia and ignoring his demand of full-submission.[46][47][48] In order to reduce the strongholds of the Assassins and the Abbasids, in the center of the Islamic world, Iran and Iraq, Guyuk appointed his best friend’s father, Eljigidei, a chief commander of the troops in Persia. Guyuk Khan restored his father’s officials to their former positions and was surrounded by the Uyghur, Naiman and Central Asian officials. He favored Han Chinese commanders who helped his father’s conquest of North China. An empire-wide census was ordered by Guyuk when his armies continued their military operations in Korea, Song China and Iraq.

Guyuk suddenly marched westwards from Karakorum in 1248. While some source wrote that he wanted to heal himself at his personal property Emyl, there is also a theory that he was probably moving to join Eljigidei to conduct a full-scale conquest of the Middle East or to make a surprise attack on his rival cousin Batu Khan in Russia. Suspicious, Sorghaghtani Beki, the widow of Tolui, secretly warned her nephew Batu of Guyuk's approach with a large army. Batu was himself going eastwards to pay homage but had another plan in his mind. Before meeting Batu, Guyuk, sick and worn out by travel, died en route at Qum-Senggir in Eastern Turkestan. According to Plano Carpini’s account, he might have been poisoned. His death aborted the full census he ordered, however local censuses took place in Russia and Turkey.

Oghul Ghaimish, Guyuk’s widow, stepped forward to take control of the empire, but she lacked the skills of her mother-in-law and her young sons Khoja and Naku and other princes challenged her authority. Batu Khan allowed her to serve as regent and suggested unruly princes listen to her words. However, she was still proud and demanded envoys of King Louis IX of France, who wanted to form an alliance against the Saracens, submission and annual tributes.

At last, Batu called a kurultai on his own territory in 1250. Members of the Ogedeid and Chagataid families refused to attend the kurultai that was held beyond the Mongolian heartland. The kurultai offered the throne to Batu Khan who had no interest in promoting himself as the new Grand Khan. Rejecting it, he instead nominated Mongke who led a Mongol army in Russia, Northern Caucasus and Hungary. The pro-Tolui faction rose up and supported his choice. Given its limited attendance and location, this kurultai was of questionable validity. Batu sent Mongke under the protection of his brothers, Berke and Tukhtemur, and his son Sartaq to assemble a formal kurultai at Kodoe Aral in the heartland. The supporters of Mongke invited Oghul Ghaimish and other main Ogedeid and Chagataid princes to attend the kurultai but they refused each time, demanding descendants of Ogedei must be khan. In response to it, Batu accused them of killing his aunt Altalaun and defying Ogedei’s nominee, Shiremun.

The Toluid reformation

When Sorghaghtani and Berke organized a second kurultai on the 1st of July, 1251, the assembled throng proclaimed Mongke Great Khan of the Mongol Empire and a few of the Ogedeid and Chagataid princes, such as his cousin Kadan and the deposed khan Khara Hulegu, acknowledged the decision. Meanwhile, Ogedei’s grandson Shiremun, who was also possible legitimate heir but ignored by Toregene, moved with his relations toward the emperor’s nomadic palace with a covert plan for an armed attack. A Kankali Turk, the falconer for Mongke, discovered the preparations for the attack and told Mongke Khan his story. At the end of the investigation under his father’s loyal servant Menggesar noyan, he found his relatives guilty but at first wanted to give them mercy as written in the Great Yassa. Mongke’s officials opposed it and then he began to punish his relatives. The trials took place on all parts of the empire from Mongolia and China in the east to Afghanistan and Iraq in the west. Estimates of the deaths of aristocrats, officials and Mongol commanders include the ruler of the Uyghurs, Oghul Gaimish, Eljigidei, Yesu Mongke, Buri and Shiremun and range from 77-300. Most of the princes of Genghisid blood involved in the plot, however, were given some form of exile. Mongke eliminated the Ogedeid and the Chagatd families’ estates and shared the western part of the empire with his ally Batu Khan. After the bloody purge, Mongke ordered a general amnesty for prisoners and captives. Since then, the power of the Great khan’s throne had passed into the lineage of Tolui forever.

Mongke was a serious man who followed the laws of his ancestors and avoided alcoholism. He decorated the capital city of Karakorum with Chinese, European and Persian architectures. One example of those constructions was a large silver tree, with pipes that discharge various drinks and a triumphant angel at its top, made by Guillaume Boucher, a Parisian goldsmith. Foreign merchants’ quarters, Buddhist monasteries, Mosques and Christian Churches were newly built.

Although he had a strong Chinese contingent, he relied heavily on Muslim and Mongol administrators. His court limited government spending and prohibited nobles and the troops from abusing civilians and issuing edicts without authorization. Mongke commuted the contribution system into a fixed poll tax collected by imperial agents and forwarded to the needy units. His court tried to lighten the tax burden to commoners by reducing tax rates. Those reforms made government expenses more predictable. Along with the reform of the tax system, he reinforced the guards at the postal relays and centralized control of monetary affairs. In another move to consolidate his power, he assigned his brothers Hulegu and Kublai to rule Persia and Mongol held China. Mongke ordered a count of the entire empire in a single census in 1252. The census was completed only when Novgorod in far northwest was counted in 1258.[49]

In order to outflank the Song Dynasty from three directions, he dispatched the Mongol armies under Kublai to Yunnan and under his uncle Iyeku to Korea. The latter and his number two, Amugan, demanded the peaceful submission of the Korean court, but Goryeo king Gonjong refused in 1252. Another force under Jalayirtai and Yesudar ravaged Korea, working together with Korean officers who had joined them in 1254-1258. At last the Korean king, who had sent tributes and non-imperial hostages before, agreed to send Mongke Khan an imperial prince as a hostage after a coup removed the Choe military faction from power.

When Kublai conquered the Dali Kingdom in 1253, Mongke’s general Qoridai stabilized his control over Tibet inducing leading monasteries to submit to Mongol rule. Subotai’s son ,Uryankhadai, reduced neighboring peoples of Yunnan to submission and beat the Tran Dynasty in northern Vietnam into temporary humiliated submission in 1258.[50]

Since the conquest of Europe from 1236 to 1241, the Mongols had not conducted any large-scale military operations. After stabilizing their finances, the Mongol leaders approved new invasions of the Middle East and south China at kurultais in Karakorum in 1253 and 1258. Mongke put Hulegu in overall charge of military and civil affairs in Persia. He appointed Chagataids and Jochids to join Hulegu’s army. The Muslims from Qazvin denounced the menace of the Nizari Ismailis, a heretical sect of Shiites. They possibly enraged Mongke Khan, dispatching their assassins to kill him. The Naiman commander Kitbuqa began to assault several Ismaili fortresses in 1253 before Hulegu deliberately advanced in 1256. Ismaili Imam or Grand Master Rukn ud-Din surrendered in 1257 and was executed. All of their strongholds in Persia were destroyed by Hulegu’s army in 1257 but Girdukh held out until 1271.

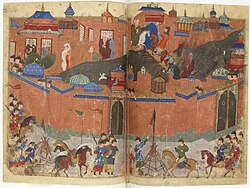

After caliph al-Mustasim’s refusal to submit, Baghdad was besieged and captured by the Mongols in 1258. With the extermination of the Abbasid Caliphate, Hulegu had an open route to Syria. His army resumed their operation, known as the Asian or Yellow Crusade in history, to the Ayyubid-ruled Syria, capturing small local states en route.[51] The sultan Al-Nasir Yusuf of the Ayyubids refused to show himself before Hulegu, however, he had accepted Mongol supremacy two decades ago. When Hulegu headed further west, the Armenians from Cilicia, the Seljuks from Rum and the crusaders from Antioch and Tripoli came to join the Mongol assault. While some cities surrendered without resisting, others such as Mayafarriqin fought back; their populations were massacred and the cities were sacked. Only Jerusalem and crusader states in Syria remained outside Mongol control. At the same time, Batu’s successor and younger brother Berke sent punitive expeditions to Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and Poland while suspecting that Hulegu’s invasion of Western Asia would result in the elimination of his predominance there.

Mongke Khan led his army to complete the conquest of China, however, his relatives convinced him not to command personally in China; ultimately he believed that this conquest was a priority task to be done for the empire. Military operations, while generally successful, were prolonged. The weather became extremely hot and the Mongols began to suffer from bloody epidemics. Mongke decided to stay instead of retiring north as the Mongols usually did. Unfortunately, he died on August 11, 1259, due to reasons disputed till this day. This event began a new chapter of history for the Mongols and forced most Mongol armies to withdraw.

Disintegration

Civil war

After the fall of Aleppo, Hulegu received news of his brother’s death and withdrew to Mughan, leaving Kitbuqa with a small contingent in 1260. The Mongols quickly lost Syria after Kitbuqa was crushed and beheaded by Sultan Qutuz of Mamluk, Egypt, at the Battle of Ain Jalut which marked the western limit of Mongol expansion. But Kublai, who heard of the great khan’s death at the Huai, continued his advance to Wuchang near the Yangtze River. Their younger brother, Arikboke, used his position in Mongolia to prepare to win the title of Great Khan. Representatives of all the family branches proclaimed him as the Khagan at the kurultai in Karakorum. Kublai abandoned the siege of Wuchang, leaving the besiegers in Ezhou and Yuezhou as soon as he learned in a message from his wife that Ariboke was raising troops. Following the advice of his Chinese staff, Kublai summoned his kurultai at Kaiping. Virtually all the senior princes and great noyans resident in North China and Manchuria supported the latter’s candidacy. Kublai’s army easily eliminated Arikboke’s supporters from the Hebei-Shangdong-Shanxi-Southern Mongolia. Kublai himself seized control of the civil administration and beat Mongke’s army, which was sympathetic to rival Great Khan Arikboke, through the efforts of the Uyghur, Lian Xixian. When Kublai sent Abishka, the Chagataid prince, to put him in charge of Chagatai’s realm, Arikboke captured him and had his own man, Alghu, crowned there. His protégé Alghu won control of the Qaraunas and arrested their commander, Sali, who was loyal to both Hulegu and Kublai.[52][53][54] After a defeat during the first armed clash, Ariboke executed Abishka in revenge. Kublai’s new administration ordered widespread emergency mobilization of military equipment and manpower while he and his cousin Khadan blockaded Arikboke in Mongolia to cut off food supplies. The resulting famine intensified when Alghu betrayed Arikboke and began supporting Kublai. Karakorum fell quickly to Kublai Khan, but Arikboke Khan temporarily retook it in 1261.

The more serious clashes between Kublai’s younger brother Hulegu and his cousin Berke, the ruler of Golden Horde, had begun in 1262. The suspicious deaths of Jochid princes in Hulegu’s service, unequal distribution of war booties and the Hulegu's massacres of the Muslims increased the anger of Berke. He considered supporting a rebellion of the Georgian Kingdom against Hulegu’s rule in 1259-1260.[55] As a result of failed rebellions, King David Ulu lost his effective control over Georgia and Armenia to the Mongols while David Narin in Imereti was forced to pay nominal homage to the Ilkhans.[56][57] The increasing tension between Berke and Hulegu was a warning to the contingents belonging to the Golden Horde which had marched with Hulegu that they had better escape. Their one section reached the Kipchak Steppe, another traversed Khorasan and a third body took refuge in Mamluk ruled Syria where they were well received by Sultan Baybars (1260–77). Hulegu harshly punished the rest of them in Iran. Berke sought a joint attack with Baybars and forged an alliance with the Mamluks against Hulegu. The Ilkhan threw his support to Kublai, while Berke strongly supported Arikboke. The latter sent Nogai to invade the Ilkhanate and the former dispatched his army under Abagha to the Golden Horde in retaliation; both sides suffered disastrous defeats. Chagatai Khan Alghu also insisted Hulegu attack Berke’s realm because he accused Berke of purging of his relatives in 1252. When the Muslim elites and the Jochid retainers in Bukhara declared their loyalty to Berke, Alghu smashed the Jochids appendages in Khorazm. In Bukhara, he and Hulegu slaughtered all the retainers of the Golden Horde and reduced their families into slavery, leaving only the Great Khan Kublai’s and Sorghaghtani’s men alive.[58]

Due to the winter disaster and the desertions of his allies, Arikboke Khan’s force weakened. He proceeded to Shangdu where he surrendered on August 21, 1264, realizing his brother’s advantages. With Arikboke defeated, the rulers of the Golden Horde, the Chagatai Khanate and the Ilkhanate acknowledged the reality of Kublai’s victory and rule.[59] When Kublai summoned them to organize another kurultai, Alghu Khan demanded security for his illegal position from Kublai in return. Despite tensions between them, both Hulegu and Berke accepted Kublai’s invitation at first.[60][61] However, they soon declined to attend the new kurultai. In the absence of a quorum for the kurultai, Kublai who was partially recognized pardoned his brother Arikboke and started preparations for his conquest of the Song Dynasty. The khanates now began to politically disintegrate, each asserting its claims and choosing its own rulers with nominal recognition from others.[62]

The Mongol Empire during the reign of Kublai Khan

When the Byzantine Empire, the ally of the Ilkhanate, captured Egyptian envoys, Berke sent an army through his vassal Bulgaria, prompting the release of the envoys and the Seljuk Sultan Kaykawus II. He tried to raise civil unrest in Anatolia using Kaykawus but failed. In the new official version of the family history, Kublai Khan refused to write Berke’s name as the khan of Golden Horde for his support to Arikboke and wars with Hulegu, however, Jochi’s family was fully recognized as legitimate family members.[63]

Khagan Kublai also reinforced Hulegu with 30,000 young Mongols in order to stabilize the political crises in western khanates.[64] As soon as Hulegu died on the 8th of February, 1264, Berke marched to cross near Tiflis, but he died on the way. Within a few months of these deaths, Alghu Khan of the Chagatai Khanate died too. Nevertheless, this sudden vacuum of power relieved Kublai’s control over the western khanates somehow. However, he named Abagha as the new Ilkhan and nominated Batu’s grandson Mongke Temur for the throne of Sarai, the capital of the Golden Horde.[65][66] The Kublaids in the east retained suzerainty over the Ilkhans (obedient khans) until the end of its regime.[67][68] Kublai also sent his protégé Baraq to overthrow the court of Oirat Orghana, the empress of the Chagatai Khanate, who put her young son Mubarak Shah on the throne in 1265, without Kublai's permission after Alghu’s death. Ogedeid prince Kaidu declined to personally come to the court of Kublai. Kublai instigated Baraq to attack him. The latter began to expand his realm northward, fighting Kaidu and the Jochids after he seized power in 1266. He also pushed out Great Khan’s overseer from Tarim basin. When Kaidu and Mongke Timur defeated him together, Baraq joined an alliance with the House of Ogedei and the Golden Horde against Kublai in the east and Abagha in the west. But smart Mongke Temur stayed out of any direct military expedition into the Empire of the Great Khan. The armies of Mongol Persia defeated Baraq’s invading forces in 1269. When Baraq died the next year, Kaidu took the control over the Chagatai Khanate.

Meanwhile, Kublai mobilized another Mongol invasion after he helped put King Wonjong (r. 1260-1274) on the throne of Goryeo in 1259 in Kanghwa. He forced two rulers of the Golden Horde and the Ilkhanate to call a truce with each other in 1270 despite the Golden Horde’s interests in the Middle East and Caucasia.[69] After the fall of Xiangyang in 1273, the Mongols proposed the final conquest of the Song Dynasty in South China. Therefore, Kublai ordered Mongke Temur to revise the second census of the Golden Horde to provide sources and men for his conquest of China.[70] The census took place in all parts of the Golden Horde, including Smolensk and Vitebsk in 1274-75. The Khans also sent Nogai to Balkan to strengthen Mongol influence there.[71]

As the Great Khan Kublai renamed the Mongol regime in China Dai Yuan in 1271, he sought to sinicize his image as Emperor of China in order to win the control of millions Chinese people. When he moved his headquarters to Khanbalic or Dadu at modern Beijing, there was an uprising in the old capital Karakorum that he barely staunched. His actions were condemned by traditionalists and his critics still accused him of being too closely tied to Chinese culture. They sent a message to him: “The old customs of our Empire are not those of the Chinese laws… What will happen to the old customs?”.[72][73] Even Kaidu attracted the other elites of Mongol Khanates, declaring himself to be a legitimate heir to the throne instead of Kublai who had turned away from the ways of Genghis Khan.[74][75] Defections from Kublai’s Dynasty swelled the Ogedeids' forces. Because Khagan Kublai wanted to make sure that he laid claims to Mongolia and the sacred place Burkhan Khaldun where Genghis was buried, Mongolia was strongly protected by the Kublaids.

The Song imperial family surrendered to the Yuan in 1276, making the Mongols the first non-Chinese people to conquer all of China. Three years later, Yuan marines crushed the last of the Song loyalists. Kublai succeeded in building powerful Empire, creating an academy, offices, trade ports and canals and sponsoring arts and science. The record of the Mongols lists 20,166 public schools created during his reign.[76] Achieving actual or nominal dominion over much of Eurasia, and having seen his successful conquest of China, Kublai was in a position to look beyond China.[77] However, Kublai’s costly invasions of Burma, Annam, Sakhalin and Champa secured only the vassal status of those countries. Mongol invasions of Japan (1274 and 1280) and Java (1293) failed. At the same time his nephew Ilkhan Abagha tried to form a grand alliance of the Mongols and the Western Europeans to defeat the Mamluks in Syria and North Africa that constantly invaded the Mongol dominions. Abagha and his uncle Kublai focused mostly on foreign alliances, and opened trade routes. Khagan Kublai dined with a large court every day, and met with many ambassadors, foreign merchants, and even offered to convert to Christianity if this religion was proved to be correct by 100 priests.

In 1277, a group of Genghisid princes under Mongke’s son Shiregi rebelled, kidnapping Kublai’s two sons and his general Antong. The rebels handed them over to Kaidu and Mongke Temur. The latter was still allied with Kaidu who fashioned an alliance with him in 1269, although, he promised Kublai Khan his military support to protect him from the Ogedeids.[78] Great Khan’s armies suppressed the rebellion and strengthened the Yuan garrisons in Mongolia and Uighurstan.

As the successor of previous great khans, Kublai had to propose all foreign affairs at least nominally. When the Muslim Ahmad Teguder seized the throne of the Ilkhanate in 1282, attempting to make peace with the Mamluks, Abagha’s old Mongols under prince Arghun appealed to the Great Khan. After the execution of Ahmad, Kublai confirmed Arghun’s coronation and awarded his commander in chief who helped his master the title of chingsang. In spite of his lack of direct administration over the western khanates and the Mongol princes’ rebellions, it seems Kublai could intervene in their affairs because Abagha’s son Arghun wrote that Great Khan Kublai ordered him to conquer Egypt in his letter to the Pope Nicolas IV.[79]

Kublai’s niece Kelmish, who was married a Khunggirat general of the Golden Horde, was powerful enough to have Kublai’s sons Nomuqan and Kokhchu returned. The court of the Golden Horde sent them back as a peace overture to the Yuan Dynasty in 1282 and induced Kaidu to release the general of Kublai. Nogai and Konchi, the khan of White Horde, established friendly relations with the Yuan and the Ilkhanate. Despite political disagreement between contending branches of the family over the office of Khagan, the economic and commercial system which trumped their squabbles continued. Thus, later developments of the Mongol Empire are seen as the commonwealth of Mongol Khanates or the Pan-Mongolism of the Mongol World while some just name it simply new Mongol Empire.[80][81][82][83]

Pan Mongolism of the New Mongol Empire

Peace treaty and political struggles

In seizing the throne in 1295, Ghazan islamized Mongol Persia. Unlike previous Ilkhans, he stopped minting coins with the name of Great Khan in Iran. But his coins in Georgia carried the traditional Mongolian formula: “Struck by Ghazan in the name of Khagan”.[84] Ghazan found it politically expedient to advertise Great Khan’s sovereignty there because the Golden Horde had long made claims on Georgia.[85] Within 4 years, he began to send tributes to the court of the Kublaids. Ghazan also appealed other khans to accept Temur Khagan as their true overlord.[86] Although, he had a seal certifying the authority of his Royal Highness to establish a country and govern its people, he was styled as a prince under the Great Khan.[87]

Ghazan continued his ancestors’ war with the Mamluks and consulted with his old Mongolian advisers in his native tongue, though he had deep faith in Almighty Allah. He defeated the Mamluk army at the battle of Wadi al-Khazandar but temporarily occupied Syria in 1299. The Chagatai Khanate and its de facto ruler Kaidu’s constant raids on Khorasan made difficulties to Ghazan’s plan to conquer Syria. Despite his wars with the Ilkhans and the Yuan, Kaidu tried to restore his influence in the Golden Horde by sponsoring his own candidate Kobeleg against Bayan (r.1299-1304), the Khan of White Horde.[88] After taking military support from the Mongol court in Russia, Bayan asked help from Temur and the Ilkhanate to organize a unified attack of the Mongol Khanates of Kaidu and his number two Duwa Khan. However, Temur was unable to send quick military support.[89] But the Yuan enlarged their counterattacks to Kaidu a year later. Ghazan was satisfied with Temur Khan’s policy that the Yuan led full-scale campaign in Central Asia. After the bloody battle with Temur’s armies near Zawkhan River in 1301, old valiant Kaidu died.[90] His death gave breathing space of internal conflicts of Mongol Khans.

In spite of his conflicts with Kaidu and Duwa, Temur established tributary relationship with the war-like Shan brothers after his series of military operations against Babai-Xifu in Thailand from 1297 to 1303. It was the end of the southern expansion of the Mongols. However, the Mongols now began to look for their unity. Duwa, who was tired of costly wars, initiated a general peace and persuaded the Ogedeids that “Let we Mongols stop shedding blood of each other. It is better to surrender to Khagan Temur”.[91][92] All Khanates approved the peace treaty in 1304 and accepted Temur's supremacy. Ghazan’s successor Oljeitu and Tokhta, the ruler of the Golden Horde, introduced the Mongol unity to the Kingdom of France and Russia while Temur ratified Oljeitu as the new Ilkhan.[93][94][95][96]

However, the fighting between Duwa and Kaidu’s son Chapar broke out shortly afterwards. With the assistance of Temur Khagan, Duwa defeated the Ogedeids. And Tokhta who strongly supported a general peace sent 20,000 men to buttress the Yuan frontier.[97] Under the general peace of the Mongols, international trade and cultural exchanges flourished between Asia and Europe. For example, patterns of the Yuan royal textiles influenced Armenian decorations and a different variety of trees and vegetables were transplanted in the provinces of the Empire including China and Iran while technological innovations spreading from Mongol dominions to the West.[98][99] The Chagataids' expansion was primarily south against India after the treaty.

After Tokhta’s death in 1312, Ozbeg (r.1313-41) seized the throne and persecuted non-Muslim Mongols. The Yuan’s influence to the Horde was largely reversed and border clashes between Mongol states continued again. Khagan Ayurbawda’s envoys seem to have backed Tokhta’s son against Ozbeg. Esen Buqa I (r. 1309-1318) was enthroned as khan of the Chagatai Khanate after suppressing a sudden rebellion by Ogedei's descendants and driving Chapar into exile in the Yuan. The Yuan and Ilkhanid armies eventually attacked the Chagatai Khanate and their Qaraunas despite the conciliatory attitude of Duwa’s son Esen Buqa. The latter asked Ozbeg Khan who was loyal ally of Egypt to form an alliance against Ayurbawda but Ozbeg refused. However, Esen buqa’s successor Kebek (d.1325) mitigated the situation, recognizing the Yuan’s nominal authority in Uighurstan after his brother’s failed wars with emperor Ayurbawda and Ilkhan Oljeitu who conquered Gilan in 1307 and attacked Mamluk fortresses in 1312-13.

Realizing economic benefits and the Genghisid legacy, Ozbeg reopened friendly relations with the Khagans of the Yuan in 1326. The Golden Horde assembled its own khan’s guards, following the Yuan style. After crushing a large rebellion in Tver in 1327, Ozbeg sent Russian prisoners to the court of Mongol Dynasty in China to show his respect. He revived the Horde's Balkan ambitions. For successfully expanding Islam, he connected Sarai city with international network of Muslim culture, building mosques and other elaborate places such as baths. Despite paying tributes to the Khagans, Ozbeg and his successors never left their claims on Caucasus and Middle East, menacing the Ilkhanate and the Chobanids in 1318, 1324, 1335 and 1356. By the second decade of the 14th century, Mongol invasions had been decreased. In 1323, Abu Said Khan (r. 1316-35) of the Ilkhanate signed a peace treaty with Egypt. By the request of him, the Yuan court awarded his custodian Chupan the title of a chief-commander of all Mongol Khanates. But Chupan’s reputation could not rescue his life in 1327.[100]

When a civil war erupted in the Yuan Dynasty in 1327-1328, Chagatai Khan Eljigidey (r.1326-29) and Kusala, the Yuan Khagan Khayisan’s son, saw their chance. The former sent the latter under the protection of his troops to Mongolia. Kusala was elected Khagan on August 30, 1329 because he was supported by a large part of Mongolian commanders and nobles. Fearing Chagataid influence on the Yuan, Tugh Temur’s (1304–1332) Kypchak commander poisoned him. In order to be accepted by other khanates as the sovereign of Mongol World, Tugh Temur, who had a good knowledge of the Chinese language and history and was also a creditable poet, calligrapher, and painter, sent Genghisid princes and notable old Mongol generals’ descendants to the Chagatai Khanate, Ilkhan Abu Said and Ozbeg. In respond of his emissaries, they all agreed to send him tributary missions each year.[101] Tugh Temur also gave lavish presents and imperial seal to Eljigidey to mollify his anger. Since the reign of Tugh Temur, the Kypchak and the Alans became even more powerful at the court of the Yuan. Pope John XXII was presented a memorandum from the eastern church describing their Pax Mongolica that "...Khagan is one of the greatest monarchs and all lords of the state, e.g. the king of Almaligh (Chagatai Khanate), emperor Abu Said and Uzbek Khan, are his subjects, saluting his holiness to pay their respects. These 3 monarchs send their overlord leopards, camels, falcons as well as precious jewelries every year. ... They acknowledge him as their absolute supreme lord.".[102]

Fall

With the death of Abu Said Bahatur Khan in 1335, the Mongol rule in Persia fell into political anarchy. A year later his successor was killed by an Oirat governor and the Ilkhanate was divided between the Suldus, the Jalayir, Qasarid Togha Temür (d.1353) and Persian warlords. Using the dissolution, the Georgians had already pushed out the Mongols when Uyghur commander Eretna established an independent state in Anatolia in 1336. Following the downfall of their Mongol masters, all-time loyal vassal Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia was threatened by the Mamluks more. Alongside the lost of Mongol colony in Persia, Mongol rulers of the Yuan and Chagatai Khanate were in a turmoil so deep that it threatened continuation of their power. Much fear arose outside the Mongol court. The Black Death began in the densely inhabited Mongol dominions from 1313 to 1331. This disastrous plague devastated all khanates, cutting off commercial ties and killing off millions. By the end of the 14th century, it may have taken 70-100 million lives of Africa, Asia and Europe. As the power of the Mongols declined, chaos erupted everywhere. Golden Horde lost all of its western dominions (including modern Belarus and Ukraine) to Poland and Lithuania from 1342 to 1369. Muslim and non-Muslim princes in the Chagatai Khanate warred with each other from 1331-1343. But the Chagatai Khanate disintegrated when non-Genghisid warlords set up their own puppet khans in Mawarannahr and Moghulistan separately. Janibeg Khan (r. 1342-1357) briefly reasserted Jochid dominance over the Chaghataids to restore their former glory. Demanding submission from an offshoot of the Ilkhanate in Azerbaijan, he boasted that "today three uluses are under my control". However, rival families of the Jochids began fighting for the throne of the Golden Horde after the assassination of his successor Berdibek Khan in 1359. Nominal Khagan Toghan Temur (r. 1333-70) was powerless to regulate those troubles because the empire nearly reached its end.[103] His court’s unbacked currency had entered a hyperinflationary spiral and the Han-Chinese people revolted due to the Yuan's late harsh restrictions. King Gongmin of Goryeo pushed Mongolian garrisons back and exterminated the family of Khagan Toghan Temur's empress while Tai Situ Changchub Gyaltsen eliminated the Mongol influence in Tibet. Increasingly isolated from their subjects, the Mongols quickly lost most of China to the Ming rebels in 1368 and fled to their homeland Mongolia. After the overthrow of the Yuan Dynasty, the Golden Horde lost touch with Mongolia and China[104] while the two main parts of Chagatai Khanate were defeated by Timur (Tamerlane) (1336–1405). The Golden Horde broke into smaller Turkic-hordes that declined steadily in power through four long centuries. Among them, the Khanate's shadow Great Horde survived till 1502 that one of its successors - Crimean Khanate sacked Sarai. The Borjigin emperors had ruled Mongolia until 1635 when the Qing Dynasty defeated them. The Khalkha under the Genghisids and their former subjects-the Oirat Mongols lost their independence to the semi-nomadic Manchus in 1691 and 1755 respectively. The Crimean Khanate was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1783.

Organization

Military setup

The Mongol military organization was simple, but effective. It was based on an old tradition of the steppe, which was a decimal system known in Iranian cultures since Achaemenid Persia, and later: the army was built up from squads of ten men each, called an arbat; ten arbats constituted a company of a hundred, called a zuut; ten zuuts made a regiment of a thousand called myanghan and ten myanghans would then constitute a regiment of ten thousand (tumen), which is the equivalent of a modern division.

Unlike other mobile-only warriors, such as the Xiongnu or the Huns, the Mongols were very comfortable in the art of the siege. They were very careful to recruit artisans and military talents from the cities they conquered, and along with a group of experienced Chinese engineers and bombardier corps, they were experts in building the trebuchet, Xuanfeng catapults and other machines with which they could lay siege to fortified positions. These were effectively used in the successful European campaigns under General Subutai. These weapons may be built on the spot using immediate local resources such as nearby trees.

Within a battle Mongol forces used extensive coordination of combined arms forces. Though they were famous for their horse archers, their lance forces were equally skilled and just as essential to their success. Mongol forces also used their engineers in battle. They used siege engines and rockets to disrupt enemy formations, confused enemy forces with smoke, and used smoke to isolate portions of an enemy force while destroying that force to prevent their allies from sending aid.

The army's discipline distinguished Mongol soldiers from their peers. The forces under the command of the Mongol Empire were generally trained, organized, and equipped for mobility and speed. To maximize mobility, Mongol soldiers were relatively lightly armored compared to many of the armies they faced. In addition, soldiers of the Mongol army functioned independently of supply lines, considerably speeding up army movement. Skillful use of couriers enabled these armies to maintain contact with each other and with their higher leaders. Discipline was inculcated in nerge (traditional hunts), as reported by Juvayni. These hunts were distinct from hunts in other cultures which were the equivalent to small unit actions. Mongol forces would spread out on line, surrounding an entire region and drive all of the game within that area together. The goal was to let none of the animals escape and to slaughter them all.

All military campaigns were preceded by careful planning, reconnaissance and gathering of sensitive information relating to the enemy territories and forces. The success, organization and mobility of the Mongol armies permitted them to fight on several fronts at once. All males aged from 15 to 60 and capable of undergoing rigorous training were eligible for conscription into the army, the source of honor in the tribal warrior tradition.

Another advantage of the Mongols was their ability to traverse large distances even in debilitatingly cold winters; in particular, frozen rivers led them like highways to large urban conurbations on their banks. In addition to siege engineering, the Mongols were also adept at river-work, crossing the river Sajó in spring flood conditions with thirty thousand cavalry in a single night during the battle of Mohi (April, 1241), defeating the Hungarian king Bela IV. Similarly, in the attack against the Muslim Khwarezmshah, a flotilla of barges was used to prevent escape on the river.

Law and governance

.

The Mongol Empire was governed by a code of law devised by Genghis, called Yassa, meaning "order" or "decree". A particular canon of this code was that the nobility shared much of the same hardship as the common man. It also imposed severe penalties – e.g., the death penalty was decreed if the mounted soldier following another did not pick up something dropped from the mount in front. On the whole, the tight discipline made the Mongol Empire extremely safe and well-run; European travelers were amazed by the organization and strict discipline of the people within the Mongol Empire.

Under Yassa, chiefs and generals were selected based on merit, religious tolerance was guaranteed, and thievery and vandalizing of civilian property was strictly forbidden. According to legend, a woman carrying a sack of gold could travel safely from one end of the Empire to another.

The empire was governed by a non-democratic parliamentary-style central assembly, called Kurultai, in which the Mongol chiefs met with the Great Khan to discuss domestic and foreign policies.

Genghis also demonstrated a rather liberal and tolerant attitude to the beliefs of others, and never persecuted people on religious grounds. This proved to be good military strategy, as when he was at war with Sultan Muhammad of Khwarezm, other Islamic leaders did not join the fight against Genghis — it was instead seen as a non-holy war between two individuals.

Throughout the empire, trade routes and an extensive postal system (yam) were created. Many merchants, messengers and travelers from China, the Middle East and Europe used the system. Genghis Khan also created a national seal, encouraged the use of a written alphabet in Mongolia, and exempted teachers, lawyers, and artists from taxes, although taxes were heavy on all other subjects of the empire.hi i am a dork At the same time, any resistance to Mongol rule was met with massive collective punishment. Cities were destroyed and their inhabitants .

Religions

Mongols were highly tolerant of most religions, and typically sponsored several at the same time. At the time of Genghis Khan, virtually every religion had found converts, from Buddhism to Christianity and Manichaeanism to Islam. To avoid strife, Genghis Khan set up an institution that ensured complete religious freedom, though he himself was a shamanist. Under his administration, all religious leaders were exempt from taxation, and from public service.[105] Mongol emperors organized competitions of religious debates among clerics with a large audience.

Initially there were few formal places of worship, because of the nomadic lifestyle. However, under Ögedei, several building projects were undertaken in Karakorum. Along with palaces, Ogodei built houses of worship for the Buddhist, Muslim, Christian, and Taoist followers. The dominant religion at that time was Shamanism, Tengriism and Buddhism, although Ogodei's wife was a Christian.[106] Later, three of the four principal khanates embraced Islam.[107]

Buddhism

Buddhists entered the service of Mongol Empire in the early 13th century. However, Buddhist monasteries established in Karakorum and their clerics were granted tax exempts, the religion was given official status by the Mongols quite later. All variants of Buddhism, such as Chinese, Tibetan and Indian Buddhism flourished, though Tibetan Buddhism was eventually favored in the imperial level under emperor Mongke. The latter appointed Namo from Kashmir a chief of all Buddhist monks.

Ogedei's son and Guyuk's younger brother, Khoten, became the governor of Ningxia and Gansu. He launched a military campaign into Tibet under the command of Generals Lichi and Dhordha. The marauding Mongols burned down Tibetan monuments such as the Reting monastery and the Gyal temple in 1240. Prince Kötön was convinced that no power in the world exceeded the might of the Mongols. However, he believed that religion was necessary in the interests of the next life. Thus he invited Sakya Pandita to his ordo. Prince Kötön was impressed and healed by Sakya Pandita's teachings and knowledge. Then he became the first known Buddhist prince of Mongol empire.

Kublai, the founder of Yuan Dynasty, also favored Buddhism. As early as 1240s, he made contacts with a Chan Buddhist monk Haiyun, who became his Buddhist adviser. Kublai's second son, whom he later officially designated as his successor of the Yuan Dynasty, was given Chinese name "Zhenjin" (literally, "True Gold") with the help of Haiyun. Khatun Chabi influenced Kublai to be converted to Buddhism. She received the Hévajra tantra initiations from Phagspa and was very impressed. Kublai appointed him his state preceptor, and later imperial preceptor, giving him power over all the Buddhist monks within the territory of the Yuan Dynasty. For the rest of the Yuan Dynasty in Mongolia and China to 1368, Tibetan lamas were most influential Buddhist clergy. But Indian Buddhist textual tradition strongly influenced the religious life in China during the Yuan Dynasty.

The Ilkhans in Iran held Paghmo gru-pa order as their appanage in Tibet and lavishly patronized a variety of Indian, Tibetan and Chinese Buddhist monks. In 1295, Ghazan persecuted Buddhists and destroyed their temples. Before his conversion he built Buddhist temple in Khorasan. The 14th century Buddhist literatures found at Chagatai Khanate show their popularity among the Mongols and the Uighurs. Tokhta of Golden Horde also encouraged lamas to settle in Russia.[108] But his policy was halted by his successor Muslim Ozbeg Khan.

Christianity

Some Mongols had been proselytized by Christian Nestorians since about the 7th century, and a few Mongols were converted to Catholicism, esp. by John of Montecorvino who was appointed by Papal states.[109]

Although, the religion never achieved great position in the Mongol Empire, many Great Khans and khans were raised by Christian mothers and tutors. Some of the major Christian figures among the Mongols were: Sorghaghtani Beki, daughter in law of Genghis Khan, and mother of the Great Khans Möngke, Kublai, Hulagu and Ariq Boke; Sartaq, khan of Golden Horde; Doquz Khatun, the mother of the ruler Abaqa; Kitbuqa, general of Mongol forces in the Levant, who fought in alliance with Christians. Marital alliances with Western powers also occurred, as in the 1265 marriage of Maria Palaiologina, daughter of Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus, with Abaqa. Tokhta, Oljeitu and Ozbeg had Greek Khatuns as well. Mongol Empire contained the lands of the Eastern Orthodox church in Caucasus and Russia, the Apostolic church in Armenia and the Assyrian Church of Nestorians in Central Asia and Persia.

The 13th century saw attempts at a Franco-Mongol alliance with exchange of ambassadors and even military collaboration with European Christians in the Holy Land. Ilkhan Abagha sent a tumen to support crusaders during the Ninth Crusade in 1271. The Nestorian Mongol Rabban Bar Sauma visited some European courts in 1287-1288. At the same time however, Islam began to take firm root amongst the Mongols, as those who embraced Christianity such as Tekuder, became Muslim.[110] After Ongud Mar Yahbh-Allaha, the monk of Kublai Khan, was elected a catholicos of the eastern Christian church in 1281, Catholic missionaries were begun to sent to all Mongol capitals.

Islam

Mongols employed many Muslims in various fields and increasingly took their advice in administrative affairs. Muslims became a favored class of officials as they were well educated and knew Turkish and Mongolian. Notable Mongol converts to Islam include Mubarak Shah of the Chagatai Khanate, Tuda Mengu of the Golden Horde, Ghazan of the Ilkhanate. Berke, who ruled Golden Horde from 1257 to 1266, was the first Muslim leader of any Mongol khanates.

Ghazan was the first Muslim khan to adopt Islam as national religion of Ilkhanate, followed by Uzbek of the Golden Horde who urged his subjects to accept the religion as well. Though in Chagatai Khanate, Mongols continued their nomadic lifestyle as Buddhism and Shamanism flourished until the 1350s. When western part of the khanate embraced Islam quickly, eastern part or Moghulistan retarded Islamization until Tughlugh Timur (1329/30-1363) accepted Islam with his thousands of subjects.

Though the Yuan Dynasty, unlike the western khanates, never converted to Islam, there had been many Muslim foreigners since Kublai Khan and his successors were tolerant of other religions, though Buddhism was the most influential religion within its territory. Contact between Yuan emperors in China and Muslim states in North Africa, India and Middle East lasted until the mid-14th century. Muslims were classified as Semuren, "various sorts", below the Mongols but above the Chinese. According to Jack Weatherford, there were more than one million Muslims in Yuan Dynasty (See also Islam during the Yuan Dynasty for more information).

Tengriism

Shamanism, which practices a form of animism with several meanings and with different characters, was a popular religion in ancient Central Asia and Siberia. The central act in the relationship between human and nature was the worship of the Blue Mighty Eternal Heaven - "Blue Sky" (Хөх тэнгэр, Эрхэт мөнх тэнгэр). Chingis Khan showed his spiritual power was greater than others and himself to be a connector to heaven after the execution of rival shaman Teb Tengri Kokhchu.

Under the Mongol Empire the khans such as Batu, Duwa, Kebek and Tokhta kept a whole college of male shamans. Those shamans were divided into bekis and others. The bekis (not confused with princess) were camped in front of the Great Khan's palace while some shamans left behind it. In spite of astrological observations and regular calendar ceremonies, Mongol shamans led armies and performed weather magic (zadyin arga). Shamans played a powerful political role behind the Mongol court.

While Ghazan converted to Islam, he still practiced some elements of Mongol shamanism. The Yassa code remained in place and Mongol shamans were allowed to remain in the Ilkhanate empire and remained politically influential throughout his reign as well as Oljeitu's. However, ancient Mongol shamanistic traditions went into decline with the demise of Oljeitu and with the rise of rulers practicing a purified form of Islam. With Islamization the shamans were no longer important as had been they in Golden Horde and Ilkhanate. But they still performed in ritual ceremonies alongside the Nestors and Buddhist monks in Yuan Dynasty.

Mail system

The Mongol Empire had an ingenious and efficient mail system for the time, often referred to by scholars as the Yam, which had lavishly furnished and well guarded relay posts known as örtöö set up all over the Mongol Empire. The yam system would be replicated later in the U.S. in the form of the Pony Express.[111] A messenger would typically travel 25 miles (40 km) from one station to the next, and he would either receive a fresh, rested horse or relay the mail to the next rider to ensure the speediest possible delivery. The Mongol riders regularly covered 125 miles per day, which is faster than the fastest record set by the Pony Express some 600 years later.

It is said that Genghis and his successor Ogedei built roads. One of roads that Ogedei built carved the Altai Range. After his enthronement, the latter organized the road system and ordered Chagatai Khanate and Golden Horde to link up roads in western parts of the Mongol Empire.[112] In order to reduce pressure on households, he set up relay stations with attached households every 25 miles (40 km). Although, someone with paiza was allowed to supply with remounts and served specified rations, those carrying military rarities used the Yam even without a paiza. News of Great Khan’s death in Karakorum, Mongolia reached the Mongols forces under Batu Khan in Central Europe within 4–6 weeks thanks to the Yam.[113] Mongke Khan limited notorious abuses of the Mongols when they use the system.

Kublai Khan, the founder of the Yuan Dynasty, built special relays for high-officials as well as ordinary relays which had hostels. During the reign of Kublai, the Yuan communication system consisted of some 1,400 postal stations, which used 50,000 horses, 8,400 oxen, 6,700 mules, 4,000 carts, and 6,000 boats.[114] In Manchuria and southern Siberia, the Mongols still used dogsled relays for the yam. On the other hand, Ghazan of the Ilkhanate restored the declining relay system in Middle East on restricted scale. He constructed few number of hostels and decreed only imperial envoys to receive a stipend. The Jochids of the Golden Horde financed their relay system by special jam tax. It is known that major Mongol khanates in the Mongol World reopened the yam among them in 1304-1305.

Economy

Appanage system

Members of Golden Kin (or Golden Family - Altan urag) was entitled to a share (khubi - хувь) of the benefits of each part of Mongol Empire just as each Mongol noble and their family, as well as each warrior, was entitled to an appropriate measure of all the goods seized in war. In 1206, Genghis Khan gave large lands with people as share to his family and loyal companions, of whom most were people of common origin. Shares of booty were distributed much more widely. Empresses, princesses and meritorious servants, as well as children of concubines, all received full shares including war prisoners.[115] For example, Kublai called 2 siege engineers from the Ilkhanate in Middle East, then under the rule of his nephew Abagha. After the Mongol conquest in 1238, the port cities in Crimea paid the Jochids custom duties and the revenues were divided among all Chingisid princes in Mongol Empire accordance with the appanage system.[116] As loyal allies, the Kublaids in East Asia and the Ilkahnids in Persia sent clerics, doctors, artisans, scholars, engineers and administrators to and received revenues from the appanages in each other's khanates.

After Genghis Khan (1206–1227) distributed nomadic grounds and cities in Mongolia and North China to his mother Hoelun, youngest brother Temuge and other members and Chinese districts in Manchuria to his another brothers, Ogedei distributed shares in North China, Khorazm, Transoxiana to the Golden Family, imperial sons in law (khurgen-хүргэн) and notable generals in 1232-1236. Great Khan Mongke divided up shares or appanages in Persia and made redistribution in Central Asia in 1251-1256.[117] Although Chagatai Khanate was the smallest in its size, Chagatai Khans owned Kat and Khiva towns in Khorazm, few cities and villages in Shanxi and Iran in spite of their nomadic grounds in Central Asia.[115] First Ilkhan Hulegu owned 25,000 households of silk-workers in China, valleys in Tibet as well as pastures, animals, men in Mongolia.[115] His descendant Ghazan of Persia sent envoys with precious gifts to Temur Khan of Yuan Dynasty to request his great-grandfather's shares in Great Yuan in 1298. It is claimed that Ghazan received his shares that were not sent since the time of Mongke Khan.[118]

Mongol and non-Mongol appanage holders demanded excessive revenues and freed themselves from taxes. Ogedei decreed that nobles could appoint darughachi and judges in the appanages instead direct distribution without the permission of Great Khan thanks to genius Khitan minister Yelu Chucai. Kublai Khan continued Ogedei's regulations somehow, however, both Guyuk and Mongke restricted the autonomy of the appanages before. Ghazan also prohibited any misfeasence of appanage holders in Ilkhanate and Yuan councillor Temuder restricted Mongol nobles' excessive rights on the appanages in China and Mongolia.[119] Kublai's successor and Khagan Temur abolished imperial son-in-law Goryeo King Chungnyeol's 358 departments which caused financial pressures to the Korean people,[120] whose country was under the control of the Mongols.[121][122][123][124][125]

The appanage system was severely affected beginning with the civil strife in the Mongol Empire in 1260-1304.[118][126] Nevertheless, this system survived. For example, Abagha of the Ilkhanate allowed Mongke Temur of the Golden Horde to collect revenues from silk-workshops in northern Persia in 1270 and Baraq of the Chagatai Khanate sent his Muslim vizier to Ilkhanate, ostensibly to investigate his appanages there (The vizier's main mission was to spy on the Ilkhanids in fact) in 1269.[127] After a peace treaty declared among Mongol Khans: Temur, Duwa, Chapar, Tokhta and Oljeitu in 1304, the system began to see a recovery. During the reign of Tugh Temur, Yuan court received a third of revenues of the cities of Mawarannahr under Chagatai Khans while Chagatai elites such as Eljigidey, Duwa Temur, Tarmashirin were given lavish presents and sharing in the Yuan Dynasty's patronage of Buddhist temples.[128] Tugh Temur was also given some Russian captives by Chagatai prince Changshi as well as Kublai's future khatun Chabi had servant Ahmad Fanakati from Ferghana valley before her marriage.[129] In 1326, Golden Horde started sending tributes to Great Khans of Yuan Dynasty again. By 1339, Ozbeg and his successors had received annually 24 thousand ding in paper currency from their Chinese appanages in Shanxi, Cheli and Hunan.[130] H.H.Howorth noted that Ozbeg's envoy required his master's shares from the Yuan court, the headquarter of the Mongol world, for the establishment of new post stations in 1336.[131] This communication ceased only with the break up, succession struggles and rebellions of Mongol Khanates.[note 2]

Money

Genghis Khan authorized the use of paper money shortly before his death in 1227. It was backed by precious metals and silk.[132] The Mongols used Chinese silver ingot as a unified money of public account, while circulating paper money in China and coins in the western areas of the empire such as Golden Horde and Chagatai Khanate. Under Ogedei Khan the Mongol government issued paper currency backed by silk reserves and founded a Department which was responsible for destroying old notes.[133] In 1253, Mongke established a Department of Monetary affairs to control the issuance of paper money in order to eliminate the overissue of the currency by Mongol and non-Mongol nobles since the reign of Great Khan Ogedei.[134] His authority established united measure based on sukhe or silver ingot, however, the Mongols allowed their foreign subjects to mint coins in the denominations and use weight they traditionally used.[135] During the reigns of Ogedei, Guyuk and Mongke, Mongol coinage increased with gold and silver coinage in Central Asia and copper and silver coins in Caucasus, Iran and southern Russia.[136]

Yuan Dynasty under Kublai Khan issued paper money backed by silver and again banknotes supplemented by cash and copper cash. Marco Polo wrote that the money was made of mulberry bark. The standardization of paper currency allowed the Yuan court to monetize taxes and reduce carrying costs of taxes in goods as did the policy of Mongke Khan. But forest nations of Siberia and Manchuria still paid their taxes in goods or commodities to the Mongols.[137] Chao was used in Yuan Dynasty only and Ilkhan Rinchindorj Gaykhatu failed to adopt the experiment in Middle East in 1294. Golden Horde, Chagatai Khanate and Ilkhanate minted their own coins in gold, silver and copper.[138] Ghazan's fiscal reforms enabled the Khanate to inaugurate a unified bimetallic currency in the Ilkhanate.[139] Chagatai Khan Kebek renewed the coinage backed by silver reserves and created unified monetary system through the realm.

Trade networks

Mongols prized their commercial and trade relationships with neighboring economies and this policy they continued during the process of their conquests and during the expansion of their empire. All merchants and ambassadors, having proper documentation and authorization, traveling through their realms were protected. This greatly increased overland trade.

Genghis Khan had encouraged foreign merchants before uniting the Mongols. They provided him information about neighboring cultures and served as diplomats and official traders of his empire. Genghis Khan and his family supplied them with capital and sent to Khorazm. Since then, their ortoq (merchant partner) business had flourished under Ogedei and Guyuk. The merchants supplied imperial palaces with clothing, food and other provisions. Great Khans gave them paiza exempting taxes and allowed to use relay stations of Mongol Empire. They also served as tax farmers in China, Russia and Iran. The merchants’ losses to banditry had to be made up by the imperial treasury. The Mongols and their partner merchants (mostly Muslims and Uyghurs) created a silver tax with unfixed interest rate. Because of money laundering and overtaxing the yam, Mongke attempted to limit abuses and sent imperial investigators to supervise the ortoq. He decreed all merchants to pay commercial and property taxes. Mongke also paid out all drafts drawn by high rank Mongol elites to merchants. This policy continued in Yuan Dynasty, however, Hulegu and his son Abagha of the Ilkhanate ignored their officials to interfere with partner merchants in Middle East. The court of Mongol Empire encouraged merchants, whether the Chinese, Indians, Persians, Central Asians or Hansa venders, to trade within their realms. Mongke-Temur granted the Genoese and the Venice exclusive rights to hold Caffa and Azov in 1267. The Golden Horde permitted the German merchants to trade in all over its territories including Russian principalities in 1270's.

During the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, European merchants, numbering hundreds, perhaps thousands, made their way from Europe to the distant land of China — Marco Polo is only one of the best known of these. Well-traveled and relatively well-maintained roads linked lands from the Mediterranean basin to China. The Mongol Empire had negligible influence on seaborne trade. Despite the unmaterialized Franco-Mongol alliance, trade of Western Europe especially Italians with the Mongol territories had rapidly increased since 1300. They established their ports, markets and guilds in China, Russia, Crimea and Iran under the Mongols.

Military conquests

Central Asia

Mongol invasion of Central Asia initially was composed of Genghis Khan's victory over and unification of the Mongol and Turkic central Asian confederations such as Merkits, Tartars, Mongols, Uighurs that eventually created the Mongol Empire. It then continued with invasion of Khwarezmid Empire in Persia.

Huge areas of Islamic Central Asia and north-east Iran were seriously depopulated.[140] Every city or town that refused surrender and resisted the Mongols was subject to destruction. In Termez, on the Oxus: “all the people, both men and women, were driven out onto the plain, and divided in accordance with their usual custom, then they were all slain”. Each soldier was required to execute a number of persons that varied according to circumstances. After the conquest of Urgench, each Mongol warrior – in an army group that might have consisted of two tumens (units of 10,000) – was required to execute 24 people. The city figures of victims were likely inflated by significant numbers of refugees.[141]

Middle East

The Mongol invasion of the Middle East consists of the conquest, by force or voluntary submission, of the areas today known as Iran, Iraq, Syria, and parts of Turkey, with further Mongol raids reaching southwards as far as Gaza into the Palestine region in 1260 and 1300. The major battles were the Battle of Baghdad (1258), when the Mongols sacked the city which for 500 years had been the center of Islamic power; and the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260, when the Muslim Egyptian Mamluks, were for the first time able to stop the Mongol advance at Ain Jalut, in the northern part of what is today known as the West Bank.

Due to a combination of political and geographic factors, such as lack of sufficient grazing room for their horses, the Mongol invasion of the Middle East turned out to be the farthest that the Mongols would ever reach, towards the Mediterranean and Africa.

East Asia

Mongol invasion of East Asia refers to the Mongols 13th and 14th century conquests under Genghis Khan and his descendants of Mongol invasion of China, the invasion of Korea which forced Korea to become a vassal, and attempted Mongol invasion of Japan, and it also can include Mongols attempted invasion of Vietnam. The biggest conquest was the total invasion of China in the end.

Europe

Mongol invasion of Europe largely constitute of their invasion and conquest of Kievan Rus, much of Russia, invasion of Poland and Hungary among others. Over the three years (1237–1240) the Mongols destroyed and annihilated all of the major cities of Russia with the exceptions of Novgorod and Pskov.[142]

Pope's envoy to Mongol Khan Giovanni de Plano Carpini, who passed through Kiev in February 1246, wrote:

"They [the Mongols] attacked Russia, where they made great havoc, destroying cities and fortresses and slaughtering men; and they laid siege to Kiev, the capital of Russia; after they had besieged the city for a long time, they took it and put the inhabitants to death. When we were journeying through that land we came across countless skulls and bones of dead men lying about on the ground. Kiev had been a very large and thickly populated town, but now it has been reduced almost to nothing, for there are at the present time scarce two hundred houses there and the inhabitants are kept in complete slavery."[143]

Political Divisions and Vassals

The early Mongol Empire was divided into 5 main parts[149] in addition to appanage khanates - there were:

- Mongolia, Southern Siberia and Manchuria under Karakorum;

- North China and Tibet under Yanjing Department;

- Khorazm, Mawarannahr and the Hami Oases under Beshbalik Department

- Persia, Georgia, Armenia, Cilicia and Turkey (former Seljuk ruled parts) under Amu Dar'ya Department

- Golden Horde. According to notable Russian scholars A.P.Grigorev and O.B.Frolova, the Ulus of Jochids had 10 provinces: 1. Khiva or Khorazm, 2. Desht-i-Kipchak, 3. Khazaria, 4. Crimea, 5. the Banks of Azov, 6. the country of Circassians, 7. Bulgar, 8. Walachia, 9. Alania, 10. Russian lands.[150]