Laughter

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (January 2009) |

Laughter is an audible expression or the appearance of happiness, or an inward feeling of joy (laughing on the inside). It may ensue (as a physiological reaction) from jokes, tickling or other stimuli. It is in most cases a very pleasant sensation.

Laughter is found among various animals, as well as in humans. Among the human species, it is a part of human behaviour regulated by the brain, helping humans clarify their intentions in social interaction and providing an emotional context to conversations. Laughter is used as a signal for being part of a group — it signals acceptance and positive interactions with others. Laughter is sometimes seemingly contagious, and the laughter of one person can itself provoke laughter from others as a positive feedback.[1] This may account in part for the popularity of laugh tracks in situation comedy television shows.

Scientifically speaking, laughter is caused by the epiglottis constricting the larynx. The study of humor and laughter, and its psychological and physiological effects on the human body is called gelotology.

Nature of laughter

Laughter is an audible expression or appearance of happiness, an inward feeling of joy or humor (laughing on the inside). It may ensue (as a physiological reaction) from jokes, tickling, and other stimuli. Strong laughter can sometimes bring an onset of tears or even moderate muscular pain. Recently researchers have shown infants as early as 17 days old have vocal laughing sounds or laughter. Early Human Development 2006This conflicts with earlier studies indicating that infants usually start to laugh at about four months of age. Robert R. Provine, Ph.D. has spent decades studying laughter. In his interview for WebMD, he indicated "Laughter is a mechanism everyone has; laughter is part of universal human vocabulary. There are thousands of languages, hundreds of thousands of dialects, but everyone speaks laughter in pretty much the same way.” Everyone can laugh. Babies have the ability to laugh before they ever speak. Children who are born blind and deaf still retain the ability to laugh.

Provine argues that “Laughter is primitive, an unconscious vocalization.” And if it seems you laugh more than others, Provine argues that it probably is genetic. In a study of the “Giggle Twins,” two exceptionally happy twins were separated at birth and not reunited until 43 years later. Provine reports that “until they met each other, neither of these exceptionally happy ladies had known anyone who laughed as much as she did.” They reported this even though they both had been brought together by their adoptive parents, whom they indicated were “undemonstrative and dour.” Provine indicates that the twins “inherited some aspects of their laugh sound and pattern, readiness to laugh, and perhaps even taste in humor.” WebMD 2002

Norman Cousins, who suffered from arthritis, developed a recovery program incorporating megadoses of Vitamin C, along with a positive attitude, love, faith, hope, and laughter induced by Marx Brothers films. "I made the joyous discovery that ten minutes of genuine belly laughter had an anesthetic effect and would give me at least two hours of pain-free sleep," he reported. "When the pain-killing effect of the laughter wore off, we would switch on the motion picture projector again and not infrequently, it would lead to another pain-free interval." He wrote about these experiences in several books.[2][3]

Research has noted the similarity in forms of laughter among various primates (humans, gorillas, orang-utans...), suggesting that laughter derives from a common origin among primate species, and has subsequently evolved in each species.[4]

A very rare neurological condition has been observed whereby the sufferer is unable to laugh out loud, a condition known as aphonogelia.[5]

Laughter and the brain

Modern neurophysiology states that laughter is linked with the activation of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which produces endorphins after a rewarding activity.

Research has shown that parts of the limbic system are involved in laughter[citation needed]. The limbic system is a primitive part of the brain that is involved in emotions and helps us with basic functions necessary for survival. Two structures in the limbic system are involved in producing laughter: the amygdala and the hippocampus[citation needed].

The December 7, 1984 Journal of the American Medical Association describes the neurological causes of laughter as follows:

- "Although there is no known 'laugh center' in the brain, its neural mechanism has been the subject of much, albeit inconclusive, speculation. It is evident that its expression depends on neural paths arising in close association with the telencephalic and diencephalic centers concerned with respiration. Wilson considered the mechanism to be in the region of the mesial thalamus, hypothalamus, and subthalamus. Kelly and co-workers, in turn, postulated that the tegmentum near the periaqueductal grey contains the integrating mechanism for emotional expression. Thus, supranuclear pathways, including those from the limbic system that Papez hypothesised to mediate emotional expressions such as laughter, probably come into synaptic relation in the reticular core of the brain stem. So while purely emotional responses such as laughter are mediated by subcortical structures, especially the hypothalamus, and are stereotyped, the cerebral cortex can modulate or suppress them."

Laughter and health

A positive link has been found between laughter and a healthy function of blood vessels with laughter causing such tissues that form using the inner lining of blood vessels, the endothelium, to dilate or expand such to increase blood flow.[6]

Causes

Common causes for laughter are sensations of joy and humor, however other situations may cause laughter as well.

A general theory that explains laughter is called the relief theory. Sigmund Freud summarized it in his theory that laughter releases tension and "psychic energy". This theory is one of the justifications of the beliefs that laughter is beneficial for one's health.[7] This theory explains why laughter can be as a coping mechanism for when one is upset, angry or sad.

Philosopher John Morreall theorizes that human laughter may have its biological origins as a kind of shared expression of relief at the passing of danger. Friedrich Nietzsche, by contrast, suggested laughter to be a reaction to the sense of existential loneliness and mortality that only humans feel.

For example, this is how this theory works in the case of humor: a joke creates an inconsistency, the sentence appears to be not relevant, and we automatically try to understand what the sentence says, supposes, doesn't say, and implies; if we are successful in solving this 'cognitive riddle', and we find out what is hidden within the sentence, and what is the underlying thought, and we bring foreground what was in the background, and we realize that the surprise wasn't dangerous, we eventually laugh with relief. Otherwise, if the inconsistency is not resolved, there is no laugh, as Mack Sennett pointed out: "when the audience is confused, it doesn't laugh" (this is the one of the basic laws of a comedian, called "exactness"). It is important to note that the inconsistency may be resolved, and there may still be no laugh. Due to the fact that laughter is a social mechanism, we may not feel like we are in danger, however, the physical act of laughing may not take place. In addition, the extent of the inconsistency (timing, rhythm, etc) has to do with the amount of danger we feel, and thus how intense or long we laugh. This explanation is also confirmed by modern neurophysiology (see section Laughter and the Brain).

Gallery

-

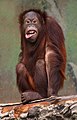

An orangutan laughing.

-

Mujeres riendo (Women Laughing) by Francisco de Goya. Oil in canvas. 1819-1823. Museo del Prado

-

A laughing girl

See also

- Death from laughter

- Evil laugh

- Gelotology

- Laughter in animals

- Laughter in Literature

- Laughter Yoga

- Nervous laughter

- Pathological laughing and crying

References

- ^ Camazine, Deneubourg, Franks, Sneyd, Theraulaz, Bonabeau, Self-Organization in Biological Systems, Princeton University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-691-11624-5 --ISBN 0-691-01211-3 (pbk.) p. 18

- ^ Cousins, Norman, The Healing Heart : Antidotes to Panic and Helplessness, New York : Norton, 1983. ISBN 0393018164

- ^ Cousins, Norman, Anatomy of an illness as perceived by the patient : reflections on healing and regeneration, introd. by René Dubos, New York : Norton, 1979. ISBN 0393012522

- ^ "Tickled apes yield laughter clue", News.BBC.co.uk, June 4, 2009

- ^ Archneurpsyc.ama-assn.org

- ^ Vlachopoulos C, Xaplanteris P, Alexopoulos N, Aznaouridis K, Vasiliadou C, Baou K, Stefanadi E, Stefanadis C. (2009). Divergent effects of laughter and mental stress on arterial stiffness and central hemodynamics. Psychosom Med. May;71(4):446-53.PMID 19251872

- ^ M.P. Mulder, A. Nijholt (2002) "Humor Research: State of the Art", citeseer.ist.psu.edu

Further reading

- Bachorowski, J.-A., Smoski, M.J., & Owren, M.J. The acoustic features of human laughter. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 110 (1581) 2001

- Bakhtin, Mikhail (1941). Rabelais and His World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Chapman, Antony J.; Foot, Hugh C.; Derks, Peter (editors), Humor and Laughter: Theory, Research, and Applications, Transaction Publishers, 1996. ISBN 1560008377. Books.google.com

- Cousins, Norman, Anatomy of an Illness As Perceived by the Patient, 1979.

- Fried, I., Wilson, C.L., MacDonald, K.A., and Behnke EJ. Electric current stimulates laughter. Nature, 391:650, 1998 (see patient AK)

- Goel, V. & Dolan, R. J. The functional anatomy of humor: segregating cognitive and affective components. Nature Neuroscience 3, 237 - 238 (2001).

- Greig, John Young Thomson, The Psychology of Comedy and Laughter, New York, Dodd, Mead and company, 1923.

- Marteinson, Peter, On the Problem of the Comic: A Philosophical Study on the Origins of Laughter, Legas Press, Ottawa, 2006. utoronto.ca

- Miller M, Mangano C, Park Y, Goel R, Plotnick GD, Vogel RA.Impact of cinematic viewing on endothelial function.Heart. 2006 Feb;92(2):261-2.

- Provine, R. R., Laughter. American Scientist, V84, 38:45, 1996. ucla.edu

- Quentin Skinner (2004). "Hobbes and the Classical Theory of Laughter" (pdf). Retrieved 2006-10-23.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) included in book: Sorell, Tom. "6". Leviathan After 350 Years. Oxford University Press. pp. 139–66. ISBN 13: 978-0-19-926461-2 ISBN 10: 0-19-926461-9.{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - Raskin, Victor, Semantic Mechanisms of Humor (1985).

- MacDonald, C., "A Chuckle a Day Keeps the Doctor Away: Therapeutic Humor & Laughter" Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services(2004) V42, 3:18-25. psychnurse.org

- Kawakami, K., et al., Origins of smile and laughter: A preliminary study Early Human Development (2006) 82, 61-66. kyoto-u.ac.jp

- Johnson, S., Emotions and the Brain Discover (2003) V24, N4. discover.com

- Panksepp, J., Burgdorf, J.,“Laughing” rats and the evolutionary antecedents of human joy? Physiology & Behavior (2003) 79:533-547. psych.umn.edu

- Milius, S., Don't look now, but is that dog laughing? Science News (2001) V160 4:55. sciencenews.org

- Simonet, P., et al., Dog Laughter: Recorded playback reduces stress related behavior in shelter dogs 7th International Conference on Environmental Enrichment (2005). petalk.org

- Discover Health (2004) Humor & Laughter: Health Benefits and Online Sources, helpguide.org

- Klein, A. The Courage to Laugh: Humor, Hope and Healing in the Face of Death and Dying. Los Angeles, CA: Tarcher/Putman, 1998.

- Ron Jenkins Subversive laughter (New York, Free Press, 1994), 13ff

- Bogard, M. Laughter and its Effects on Groups. New York, New York: Bullish Press, 2008.

- Humor Theory. The formulae of laughter by Igor Krichtafovitch, Outskitspress, 2006, ISBN 9781598002225

External links

- The Origins of Laughter, chass.utoronto.ca

- Human laughter up to 16 million years old, cosmosmagazine.com

- Humor therapy for cancer patients, cancer.org

- Etymology of Gelotology, wordinfo.info

- More information about Gelotology from the University of Washington, faculty.washington.edu

- How Stuff Works - Laughter, howstuffworks.com

- LaughterYoga.org

- Listentolaughter.com

- Formulae of laughter, lebed.com

- WNYC's Radio Lab radio show: Is Laughter just a Human Thing?, wnyc.org

- Medical Benefits of Laughter, youtube.com