Spanish flu

The 1918 flu pandemic (the Spanish Flu) was an influenza pandemic that spread widely across the world. It may have been caused by an unusually virulent and deadly influenza A virus strain of subtype H1N1[citation needed]. Historical and epidemiological data are inadequate to identify the geographic origin.[1] Most victims were healthy young adults, in contrast to most influenza outbreaks which predominantly affect juvenile, elderly, or weakened patients. The flu pandemic was implicated in the outbreak of encephalitis lethargica in the 1920s.[2]

The pandemic lasted from March 1918 to June 1920,[3] spreading even to the Arctic and remote Pacific islands. Between 50 to 100 million died, making it the deadliest natural disaster in human history.[4][5][6][7][8] An estimated 50 million people, about 3% of the world's population (1.6 billion), died of the disease. 500 million, or 1/3 were infected.[5]

Tissue samples from frozen victims were used to reproduce the virus for study. Given the extreme virulence, some question the wisdom of such research. Among the conclusions of this research is that the virus kills via a cytokine storm (overreaction of the body's immune system) which perhaps explains its unusually severe nature and the concentrated age profile of its victims. The strong immune systems of young adults ravaged the body, whereas the weaker immune systems of children and middle-aged adults caused fewer deaths.[9]

Origins of name

Although the first cases were registered in the continental U.S, and the rest of Europe long before getting to Spain, the 1918 pandemic received its nickname "Spanish flu" because Spain, a neutral country in WWI, had no censorship of news regarding the disease and its consequences. Spanish King Alfonso XIII became gravely ill and was the highest-profile patient about whom there was coverage, hence the widest and most reliable news coverage came from Spain, thus giving the false impression that Spain was most affected.[9][10]

History

While World War I did not cause the flu, the close troop quarters and massive troop movements hastened the pandemic and probably increased transmission, augmented mutation and may have increased the lethality of the virus. Some speculate that the soldiers' immune systems were weakened by malnourishment as well as the stresses of combat and chemical attacks, increasing their susceptibility.[11] Andrew Price-Smith has made the controversial argument that the virus helped tip the balance of power in the latter days of the war towards the Allied cause. He provides data that the viral waves hit the Central Powers before they hit the Allied powers, and that both morbidity and mortality in Germany and Austria were considerably higher than in Britain and France.[12]

A large factor of worldwide flu occurrence was increased travel. Modern transportation systems made it easier for soldiers, sailors, and civilian travelers to spread the disease.

Source

Some theorized that the flu originated in the Far East.[13] Dr. C. Hannoun, leading expert of the 1918 flu for the Institut Pasteur, asserted that the former virus was likely to have come from China, mutated in the United States near Boston, and spread to Brest, France, Europe's battlefields, Europe, and the world using Allied soldiers and sailors as main spreaders.[14] Hannoun considered several other theories of origin, such as Spain, Kansas, and Brest, as being possible but not likely.

Historian Alfred W. Crosby speculated that the flu originated in Kansas.[15] Political scientist Andrew Price-Smith published data from the Austrian archives suggesting that the influenza had earlier origins, beginning in Austria in the spring of 1917.[16] Popular writer John Barry echoed Crosby in describing Haskell County, Kansas as the likely point of origin.[17] In the United States the disease was first observed at Fort Riley, Kansas, on March 4, 1918,[18] and Queens, New York, on March 11, 1918. In August 1918, a more virulent strain appeared simultaneously in Brest, France, in Freetown, Sierra Leone, and in the U.S. at Boston, Massachusetts. The Allies of World War I came to call it the Spanish flu, primarily because the pandemic received greater press attention after it moved from France to Spain in November 1918. Spain was not involved in the war and had not imposed wartime censorship.[19]

Investigative work by a British team, led by virologist John Oxford[20] of St Bartholomew's Hospital and the Royal London Hospital, has suggested that a principal British troop staging camp in Étaples, France was at the center of the 1918 flu pandemic or was the location of a significant precursor virus.[21]

Mortality

The global mortality rate from the 1918/1919 pandemic is not known, but it is estimated that 10% to 20% of those who were infected died. With about a third of the world population infected, this case-fatality ratio means that 3% to 6% of the entire global population died.[24] Influenza may have killed as many as 25 million in its first 25 weeks. Older estimates say it killed 40–50 million people[4] while current estimates say 50—100 million people worldwide were killed.[25] This pandemic has been described as "the greatest medical holocaust in history" and may have killed more people than the Black Death.[26]

As many as 17 million died in India, about 5% of the population.[27] In Japan, 23 million people were affected, and 390,000 died.[28] In the U.S., about 28% of the population suffered, and 500,000 to 675,000 died.[29] In Britain as many as 250,000 died; in France more than 400,000.[30] In Canada 50,000 died.[31] Entire villages perished in Alaska[32] and southern Africa.[which?] Tafari Makonnen (the future Haile Selassie) was one of the first Ethiopians who contracted influenza but survived,[33] although many of his subjects did not; estimates for the fatalities in the capital city, Addis Ababa, range from 5,000 to 10,000, or higher,[34] while in British Somaliland one official there estimated that 7% of the native population died.[35] In Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), 1.5 million assumed died from 30 million inhabitants.[36] In Australia an estimated 12,000 people died and in the Fiji Islands, 14% of the population died during only two weeks, and in Western Samoa 22%.

This huge death toll was caused by an extremely high infection rate of up to 50% and the extreme severity of the symptoms, suspected to be caused by cytokine storms.[4] Symptoms in 1918 were so unusual that initially influenza was misdiagnosed as dengue, cholera, or typhoid. One observer wrote, "One of the most striking of the complications was hemorrhage from mucous membranes, especially from the nose, stomach, and intestine. Bleeding from the ears and petechial hemorrhages in the skin also occurred."[25] The majority of deaths were from bacterial pneumonia, a secondary infection caused by influenza, but the virus also killed people directly, causing massive hemorrhages and edema in the lung.[22]

The unusually severe disease killed between 2 and 20% of those infected, as opposed to the usual flu epidemic mortality rate of 0.1%.[22][25] Another unusual feature of this pandemic was that it mostly killed young adults, with 99% of pandemic influenza deaths occurring in people under 65, and more than half in young adults 20 to 40 years old.[37] This is unusual since influenza is normally most deadly to the very young (under age 2) and the very old (over age 70), and may have been due to partial protection caused by exposure to a previous Russian flu pandemic of 1889.[38]

Patterns of fatality

Typical influenzas kill weak individuals, such as infants (aged 0–2 years), the elderly, and the immunocompromised. Older adults may have had some immunity from the earlier Russian flu pandemic of 1889.[38] Another oddity was that the outbreak was widespread in the summer and autumn (in the Northern Hemisphere); influenza is usually worse in winter.[39]

In fast-progressing cases, mortality was primarily from pneumonia, by virus-induced pulmonary consolidation. Slower-progressing cases featured secondary bacterial pneumonias, and there may have been neural involvement that led to mental disorders in some cases. Some deaths resulted from malnourishment and even animal attacks in overwhelmed communities.[40]

Deadly second wave

The second wave of the 1918 pandemic was much deadlier than the first. The first wave had resembled typical flu epidemics; those most at risk were the sick and elderly, while younger, healthier people recovered easily. But in August, when the second wave began in France, Sierra Leone and the United States,[41] the virus had mutated to a much deadlier form. This has been attributed to the circumstances of the First World War.[42] In civilian life evolutionary pressures favour a mild strain: those who get really sick stay home, and those mildly ill continue with their lives, go to work and go shopping, preferentially spreading the mild strain. In the trenches the evolutionary pressures were reversed: soldiers with a mild strain remained where they were, while the severely ill were sent on crowded trains to crowded field hospitals, spreading the deadlier virus. So the second wave began and the flu quickly spread around the world again.[43] It was the same flu, in that most of those who recovered from first-wave infections were immune, but it was now far more deadly, and the most vulnerable people were those who were like the soldiers in the trenches—young, otherwise healthy adults.[44] Consequently, during modern pandemics, health officials pay attention when the virus reaches places with social upheaval, looking for deadlier strains of the virus.[43]

Devastated communities

Even in areas where mortality was low, so many were incapacitated that much of everyday life was hampered. Some communities closed all stores or required customers to leave orders outside. There were reports that the health-care workers could not tend the sick nor the gravediggers bury the dead because they too were ill. Mass graves were dug by steam shovel and bodies buried without coffins in many places.[45] Several Pacific island territories were particularly hard-hit. The pandemic reached them from New Zealand, which was too slow to implement measures to prevent ships carrying the flu from leaving its ports. From New Zealand the flu reached Tonga (killing 8% of the population), Nauru (16%) and Fiji (5%, 9,000 people). Worst affected was Western Samoa, a territory then under New Zealand military administration. A crippling 90% of the population was infected; 30% of adult men, 22% of adult women and 10% of children were killed. By contrast, the flu was kept away from American Samoa by a commander who imposed a blockade.[46] In New Zealand itself 8,573 deaths were attributed to the 1918 pandemic influenza, resulting in a total population fatality rate of 7.4 per thousand (0.74%) .[47]

Less affected areas

In Japan, 257,363 deaths were attributed to influenza by July 1919, giving an estimated 0.425% mortality rate, much lower than nearly all other Asian countries for which data are available. The Japanese government severely restricted maritime travel to and from the home islands when the pandemic struck.

In the Pacific, American Samoa[48] and the French colony of New Caledonia[49] also succeeded in preventing even a single death from influenza through effective quarantines. In Australia, nearly 12,000 perished.[50]

End of the pandemic

After the lethal second wave struck in the autumn of 1918, new cases dropped abruptly — almost to nothing after the peak in the second wave.[9] In Philadelphia for example, 4,597 people died in the week ending October 16, but by November 11 influenza had almost disappeared from the city. One explanation for the rapid decline of the lethality of the disease is that doctors simply got better at preventing and treating the pneumonia which developed after the victims had contracted the virus, although John Barry states in his book that researchers have found no evidence to support this. Another theory holds that the 1918 virus mutated extremely rapidly to a less lethal strain. This is a common occurrence with influenza viruses: there is a tendency for pathogenic viruses to become less lethal with time, providing more living hosts.[9]

Cultural impact

In the United States, the United Kingdom and other countries, despite the relatively high morbidity and mortality rates that resulted from the epidemic in 1918–1919, the Spanish flu began to fade from public awareness over the decades until the arrival of news about bird flu and other pandemics in the 1990s and 2000s.[51] This has led some historians to label the Spanish flu a "forgotten pandemic".[15]

There are various theories why the Spanish flu was "forgotten". The rapid pace of the pandemic, which killed most of its victims in the United States, for example, within a period of less than nine months, resulted in limited media coverage. The general population was familiar with patterns of pandemic disease in the late 19th and early 20th centuries: typhoid, yellow fever, diphtheria, and cholera all occurred near the same time. These outbreaks probably lessened the significance of the influenza pandemic for the public.[52]

In addition the outbreak coincided with the deaths and media focus on the First World War.[53] Another explanation involves the age group affected by the disease. The majority of fatalities, from both the war and the epidemic, were among young adults. The deaths caused by the flu may have been overlooked due to the large numbers of deaths of young men in the war or as a result of injuries. When people read the obituaries, they saw the war or post-war deaths and the deaths from the influenza side by side. Particularly in Europe, where the war's toll was extremely high, the flu may not have had a great, separate, psychological impact, or may have seemed a mere "extension" of the war's tragedies.[54] The duration of the pandemic and the war could have also played a role: the disease would usually only affect a certain area for a month before leaving, while the war, which most expected to end quickly, had lasted for four years by the time the pandemic struck. This left little time for the disease to have a significant impact on the economy.

One of the few major works of American literature dealing largely with the Spanish flu is Katherine Anne Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider. In 1935 John O'Hara wrote a long short story, "The Doctor's Son", about the experience of his fictional alter ego during the flu epidemic in a Pennsylvania coal mining town. In 1937 American novelist William Keepers Maxwell, Jr. wrote They Came Like Swallows, a fictional reconstruction of the events surrounding his mother's death from the flu. Mary McCarthy, the American novelist and essayist, wrote about her parents' deaths in Memories of a Catholic Girlhood. Bodie and Brock Thoene's "Shiloh Legacy" series led off with an account of the Spanish flu in New York and Arkansas in their novel In My Father's House (1992). In 1997 David Morrell's short story "If I Die Before I Wake"—dealing with a small American town during the second wave—was published in the anthology Revelations, which was framed by Clive Barker. In 2006 Thomas Mullen published a novel called The Last Town on Earth about the impact of the Spanish flu on a fictional mill town in Washington. In 2005 the Canadian television series ReGenesis presented fictional research into the Spanish Flu and Encephalitis Lethargica. In 2008, Dennis Lehane's novel "The Given Day" described the pandemic from the point of view of one of the novel's protagonists Boston police officer Danny Coughlin; and also from the point of view of protagonist Luther Laurence, a black hotel houseman in Tulsa.

Spanish flu research

The origin of the Spanish flu pandemic, and the relationship between the near simultaneous outbreaks in humans and swine, have been controversial. One theory is that the virus strain originated at Fort Riley, Kansas, by two genetic mechanisms– genetic drift and antigenic shift– in viruses in poultry and swine which the fort bred for food; the soldiers were then sent from Fort Riley around the world, where they spread the disease. Similarities between a reconstruction of the virus and avian viruses, combined with the human pandemic preceding the first reports of influenza in swine, led researchers to conclude that the influenza virus jumped directly from birds to humans, and swine caught the disease from humans.[55][56] Others have disagreed,[57] and more recent research has suggested that the strain may have originated in a non-human mammalian species.[58] An estimated date for its appearance in mammalian hosts has been put at the period 1882–1913.[59] This ancestor virus diverged about 1913–1915 into two clades which gave rise to the classical swine and human H1N1 influenza lineages. The last common ancestor of human strains dates to between February 1917 and April 1918. Because pigs are more readily infected with avian influenza viruses than are humans, it is suggested that they were the original recipient of the virus, passing the virus to humans sometime between 1913 and 1918.

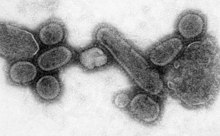

An effort to recreate the 1918 flu strain (a subtype of avian strain H1N1) was a collaboration among the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory and Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City; the effort resulted in the announcement (on October 5, 2005) that the group had successfully determined the virus's genetic sequence, using historic tissue samples recovered by pathologist Johan Hultin from a female flu victim buried in the Alaskan permafrost and samples preserved from American soldiers.[60]

On January 18, 2007, Kobasa et al. reported that monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) infected with the recreated strain exhibited classic symptoms of the 1918 pandemic and died from a cytokine storm[61]—an overreaction of the immune system. This may explain why the 1918 flu had its surprising effect on younger, healthier people, as a person with a stronger immune system would potentially have a stronger overreaction.[62]

On September 16, 2008, the body of Yorkshireman Sir Mark Sykes was exhumed to study the RNA of the Spanish flu virus in efforts to understand the genetic structure of modern H5N1 bird flu. Sykes had been buried in 1919 in a lead coffin which scientists hope will have helped preserve the virus.[63]

In December 2008, research by Yoshihiro Kawaoka of the University of Wisconsin linked the presence of three specific genes (termed PA, PB1, and PB2) and a nucleoprotein derived from 1918 flu samples to the ability of the flu virus to invade the lungs and cause pneumonia. The combination triggered similar symptoms in animal testing.[64]

Gallery

-

Albertan farmers wearing masks to protect themselves from the flu.

-

Policemen wearing masks provided by the American Red Cross in Seattle, 1918

-

A street car conductor in Seattle in 1918 refusing to allow on passengers who are not wearing a mask

-

Influenza ward at Walter Reed Hospital during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-1919.

Victims

Notable fatalities

- Admiral Dot (1864–1918), circus performer under P. T. Barnum[65]

- Amadeo de Souza Cardoso, Portuguese painter, (October 25, 1918)

- Francisco de Paula Rodrigues Alves, Brazilian re-elected president, died before taking office(January 16, 1919)[66]

- Guillaume Apollinaire, French poet (November 9, 1918)

- Felix Arndt, American pianist (October 16, 1918)

- Louis Botha, first Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa, (August 27, 1919)[67]

- Randolph Bourne, American progressive writer and public intellectual, (December 22, 1918)[68]

- Dudley John Beaumont, husband of the Dame of Sark (November 24, 1918) [69]

- Larry Chappell, American baseball player, (November 8, 1918)

- Angus Douglas, Scottish international footballer, (December 14, 1918)

- Harry Elionsky, American champion long-distance swimmer[67]

- Ella Flagg Young, American educator (October 26, 1918)

- George Freeth, father of modern surfing and lifeguard (April 7, 1919)

- Sophie Halberstadt-Freud, daughter of Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, (1920)

- Irma Cody Garlow, daughter of Buffalo Bill Cody[65]

- Harold Gilman, British painter (February 12, 1919)

- Henry G. Ginaca, American engineer, inventor of the Ginaca machine (October 19, 1918)

- Myrtle Gonzalez, American film actress (October 22, 1918)[68]

- Kenneth Sawyer Goodman, namesake of Chicago's famous Goodman Theatre

- Edward Kidder Graham, President of the University of North Carolina (October 26, 1918)

- Charles Tomlinson Griffes, American composer (April 8, 1920)

- Joe Hall, Montreal Canadiens defenceman, a member of the Hockey Hall of Fame (April 6, 1919)

- Phoebe Hearst, mother of William Randolph Hearst, (April 13, 1919)

- Bohumil Kubišta, Czech painter, (November 27, 1918)

- Hans E. Lau, Danish astronomer, (October 16, 1918)[68]

- Julian L'Estrange[3] stage and screen actor, husband of actress Constance Collier (October 22, 1918)

- Ruby Lindsay, an Australian illustrator and painter, (12 March 1919)

- Harold Lockwood, American silent film star, (October 19, 1918)[65]

- Francisco Marto, Fátima child (April 4, 1919)

- Jacinta Marto, Fátima child (February 20, 1920)

- Alan Arnett McLeod, Victoria Cross recipient, (6 November 1918)

- Dan McMichael, manager of Scottish association football club Hibernian (1919)

- Leon Morane, French aircraft company founder and pre-WW1 aviator (October 20, 1918)

- William Francis Murray, Postmaster of Boston and former U.S. Representative (September 21, 1918)

- Sir Hubert Parry, British composer, (October 7, 1918)

- Henry Ragas, pianist of the Original Dixieland Jass Band

- William Leefe Robinson, Victoria Cross recipient, (December 31, 1918)

- Edmond Rostand, French dramatist, best known for his play Cyrano de Bergerac, (December 2, 1918)

- Egon Schiele, Austrian painter (October 31, 1918, Vienna).[70]

- Reggie Schwarz, South African cricketer and rugby player (November 18, 1918)[68]

- Yakov Sverdlov, Bolshevik party leader and official of pre-USSR Russia (March 16, 1919)

- Mark Sykes, British politician and diplomat, body exhumed 2008 for scientific research (February 16, 1919)

- Frederick Trump, Grandfather of businessman Donald Trump, (March 30, 1918)

- Prince Umberto, Count of Salemi, Member of Italian royal family, (October 19, 1918)

- Max Weber, German political economist and sociologist (June 14, 1920)

- Prince Erik, Duke of Västmanland (Erik Gustav Ludvig Albert Bernadotte), Prince of Sweden, Duke of Västmanland (September 20, 1918)

- Vera Kholodnaya, Russian actress (February 16, 1919)

- Dark Cloud (actor), aka Elijah Tahamont, American Indian actor, in Los Angeles (1918).

- Franz Karl Salvator (1893–1918), son of Archduchess Marie Valerie of Austria and Archduke Franz Salvator, grandson of Empress Elisabeth of Bavaria and Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, died unmarried and childless.

- Anaseini Takipō, Queen of Tonga from 1909, consort of King George Tupou II of Tonga, survived by one daughter, (November 26, 1918)

- King Watzke, American violinist and bandleader, (1920)[68]

- Bill Yawkey, Major League Baseball executive and owner of the Detroit Tigers, in Augusta, Georgia (March 5, 1919)

Notable survivors

- Alexandrine of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1879–1952), Queen of Denmark[40]

- Alfonso XIII of Spain (1866-1941), King of Spain[9]

- Walter Benjamin, (1892–1940) German-Jewish philosopher and Marxist literary critic.[71]

- Walt Disney (1901–1966), cartoonist.[40]

- Peter Fraser (1884–1950), New Zealand prime minister.[40]

- David Lloyd George (1863–1945), British prime minister.[40]

- Lillian Gish (1893–1993), early motion picture star.[72]

- Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992), economist and Nobel Laureate

- Joseph Joffre (1852–1931), French World War I general, victor of the Marne.[40]

- Prince Maximilian of Baden (1867–1929), Chancellor of Germany during the armistice.[40]

- William Keepers Maxwell, Jr. (August 16, 1908–July 31, 2000) American novelist and editor

- Edward Munch, (1863–1944) Norwegian painter.[73]

- Georgia O'Keeffe, (1887–1986) American modernist painter.[74]

- John J. Pershing (1860–1948) American general.[40]

- Mary Pickford (1892–1979), early motion picture star.[40]

- Katherine Anne Porter (1890–1980), Pulitzer Prize-winning American writer[40]

- Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), American president[40]

- Haile Selassie (1892–1975), Emperor of Ethiopia.[33]

- Leo Szilard (1898–1964), nuclear physicist, discoverer of the nuclear chain reaction.[75]

- Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859–1941)[40]

- Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924) American president.[40]

See also

References

- Notes

- ^ "1918 Influenza Pandemic | CDC EID". Archived from the original on 2009-10-01. Retrieved 2009-09-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Vilensky JA, Foley P, Gilman S (2007). "Children and encephalitis lethargica: a historical". Pediatr. Neurol. 37 (2): 79–84. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.04.012. PMID 17675021.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Institut Pasteur. La Grippe Espagnole de 1918 (Powerpoint presentation in French).

- ^ a b c Patterson, KD (1991). "The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic". Bull Hist Med. 65 (1): 4–21. PMID 2021692.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Jeffery K. Taubenberger and David M. Morens. 1918 Influenza: the Mother of All Pandemics, January, 2006. Retrieved on May 9, 2009. Archived 2009-10-01.

- ^ Tindall 2007

- ^ The 1918 Influenza Pandemic. Accessed 2009-05-01. Archived 2009-05-04.

- ^ Johnson NP, Mueller J (2002). "Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918–1920 "Spanish" influenza pandemic". Bull Hist Med. 76 (1): 105–15. doi:10.1353/bhm.2002.0022. PMID 11875246.

- ^ a b c d e Barry 2004

- ^ Duncan 2003, p. 7

- ^ Ewald 1994, p. 110.

- ^ Andrew Price-Smith, Contagion and Chaos, MIT Press, 2009.

- ^ 1918 killer flu secrets revealed. BBC News. February 5, 2004.

- ^ Pr. C. HANNOUN :

La Grippe, Ed Techniques EMC (Encyclopédie Médico-Chirurgicale), Maladies infectieuses, 8-069-A-10, 1993.

Documents de la Conférence de l'Institut Pasteur : La Grippe Espagnole de 1918. - ^ a b Crosby 2003

- ^ Andrew Price-Smith, Contagion and Chaos, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009.

- ^ Barry, John. The site of origin of the 1918 influenza pandemic and its public health implications, Journal of Translational Medicine, 2:3. Accessed 2009-05-01. Archived 2009-05-04.

- ^ Avian Bird Flu. 1918 Flu (Spanish flu epidemic).

- ^ Channel 4 - News - Spanish flu facts.

- ^ "EU Research Profile on Dr. John Oxford". Archived from the original on 2009-05-11. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Connor, Steve, "Flu epidemic traced to Great War transit camp", The Guardian (UK), Saturday, 8 January 2000. Accessed 2009-05-09. Archived 2009-05-11.

- ^ a b c Taubenberger, J (2006). "1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics". Emerg Infect Dis. 12 (1): 15–22. PMID 16494711. Archived from the original on 2009-10-01. Retrieved 2009-09-28.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Taubenberger" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "1918 Influenza: the Mother of All Pandemics". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2009-10-01. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

Taubenberger, J., Morens, M. (2006). "1918 Influenza Pandemic". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2009-10-01. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

{{cite web}}: Text "CDC EID" ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Knobler 2005, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Potter, CW (2006). "A History of Influenza". J Appl Microbiol. 91 (4): 572–579. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01492.x. PMID 11576290.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Flu experts warn of need for pandemic plans. British Medical Journal.

- ^ "Spanish Influenza in Japanese Armed Forces, 1918–1920". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- ^ Pandemics and Pandemic Threats since 1900, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

- ^ The "bird flu" that killed 40 million. BBC News. October 19, 2005.

- ^ "A deadly virus rages throughout Canada at the end of the First World War". CBC History.

- ^ "The Great Pandemic of 1918: State by State". Archived from the original on 2009-05-06. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Harold Marcus, Haile Sellassie I: The formative years, 1892–1936 (Trenton: Red Sea Press, 1996), pp. 36f; Pankhurst 1990, p. 48f.

- ^ Pankhurst 1990, p. 63.

- ^ Pankhurst 1990, p. 51f.

- ^ Historical research report from University of Indonesia, School of History, as reported in Emmy Fitri. Looking Through Indonesia's History For Answers to Swine Flu. The Jakarta Globe. 28 October 2009 edition.

- ^ Simonsen, L (1998). "Pandemic versus epidemic influenza mortality: a pattern of changing age distribution". J Infect Dis. 178 (1): 53–60. PMID 9652423.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b O Hansen, 1923, Undersøkelser om influenzaens opptræden specielt i Bergen 1918–1922 Skrifter utgit ved Klaus Hanssens Fond. Bergen: Medicinsk avdeling, Haukeland Sykehus, 1923: 3.

- ^ Key Facts about Swine Influenza [1] accessed 22:45 GMT-6 30/04/2009. Archived 2009-05-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Collier 1974

- ^ UK Parliament - http://www.parliament.the-stationery-office.com/pa/ld200506/ldselect/ldsctech/88/88.pdf. Accessed 2009-05-06. Archived 2009-05-08.

- ^ Gladwell, Malcolm. "The Dead Zone". The New Yorker (September 29, 1997): 55.

- ^ a b Gladwell, Malcolm. "The Dead Zone". The New Yorker (September 29, 1997): 63.

- ^ Gladwell, Malcolm. "The Dead Zone". The New Yorker (September 29, 1997): 56.

- ^ Fortune article "Viruses of Mass Destruction" written 1st November 2004 [2] accessed 01:12 GMT+1 30/04/2009

- ^ DENOON, Donald, “New Economic Orders: Land, Labour and Dependency”, in DENOON, Donald (éd.), The Cambridge History of the Pacific Islanders, Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-521-00354-7, p. 247.

- ^ RICE, Geoffrey, Black November; the 1918 Ifluenza Pandemic in New Zealand, University of Canterbury Press, 2005, ISBN 1877257354, p. 221.

- ^ World Health Organization Writing Group (2006). "Nonpharmaceutical interventions for pandemic influenza, international measures". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Emerging Infectious Diseases (EID) Journal. 12 (1): 189.

- ^ Anne Grant, History House, Portland. Influenza Pandemic 1919. Portland Victoria.

- ^ Honigsbaum

- ^ Morrisey, Carla R. "The Influenza Epidemic of 1918." Navy Medicine 77, no. 3 (May-June 1986): 11–17.

- ^ Crosby 2003, pp. 320–322.

- ^ Simonsen, L; Clarke M, Schonberger L, Arden N, Cox N, Fukuda K (Jul 1998). "Pandemic versus epidemic influenza mortality: a pattern of changing age distribution."

- ^ Sometimes a virus contains both avian adapted genes and human adapted genes. Both the H2N2 and H3N2 pandemic strains contained avian flu virus RNA segments. "While the pandemic human influenza viruses of 1957 (H2N2) and 1968 (H3N2) clearly arose through reassortment between human and avian viruses, the influenza virus causing the 'Spanish flu' in 1918 appears to be entirely derived from an avian source (Belshe 2005)." (from Chapter Two: Avian Influenza by Timm C. Harder and Ortrud Werner, an excellent free on-line book called Influenza Report 2006 which is a medical textbook that provides a comprehensive overview of epidemic and pandemic influenza.)

- ^ Taubenberger JK, Reid AH, Lourens RM, Wang R, Jin G, Fanning TG (2005). "Characterization of the 1918 influenza virus polymerase genes". Nature. 437 (7060): 889–93. doi:10.1038/nature04230. PMID 16208372.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Antonovics J, Hood ME, Baker CH (2006). "Molecular virology: was the 1918 flu avian in origin?". Nature. 440 (7088): E9, discussion E9–10. doi:10.1038/nature04824. PMID 16641950.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vana G, Westover KM (2008). "Origin of the 1918 Spanish influenza virus: a comparative genomic analysis". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 47 (3): 1100–10. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.02.003. PMID 18353690.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dos Reis M, Hay AJ, Goldstein RA.(2009) Using Non-Homogeneous Models of Nucleotide Substitution to Identify Host Shift Events: Application to the Origin of the 1918 'Spanish' Influenza Pandemic Virus. J Mol Evol

- ^ Center for Disease Control: Researchers Reconstruct 1918 Pandemic Influenza Virus; Effort Designed to Advance Preparedness Retrieved on 2009-09-02

- ^ Kobasa, Darwyn (2007). "Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus". Nature. 445 (7125): 319–323. doi:10.1038/nature05495. PMID 17230189.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ USA Today: Research on monkeys finds resurrected 1918 flu killed by turning the body against itself Retrieved on 2008-08-14.

- ^ BBC News: Body exhumed in fight against flu Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ^ "Reuters. December 29, 2008. Researchers unlock secrets of 1918 flu pandemic.". Reuters.com. 2008-12-29. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ^ a b c "Influenza 1918 - Among the Victims". American Experience, PBS. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ^ Frank D. McCann (2004). Soldiers of the Pátria: a history of the Brazilian Army, 1889-1937. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804732222.

- ^ a b Duncan 2003, p. 16

- ^ a b c d e dMAC Health Digest.

- ^ Hathaway, Sibyl (1962). [http://www.archive.org/details/dameofsark006367mbp

- Dame of Sark: An Autobiography. 2nd printing]. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc. p. 59.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); line feed character in|url=at position 51 (help) - ^ Frank Whitford, Expressionist Portraits, Abbeville Press, 1987, p. 46. ISBN 0896597806

- ^ Sholem, Gershom. Walter Benjamin: The Story of a Friendship. Trans. The Jewish Publication Society of America. London: Faber & Faber, 1982. 76.

- ^ Lillian Gish: The Movies, Mr. Griffith, and Me, ISBN 0135366496.

- ^ Munch Museum, "A timeline of Munch's life".Munch Museum. Accessed 2009-05-24. Archived 2009-05-27.

- ^ Roxana Robinson, Georgia O'Keeffe: A Life. University Press of New England, 1989. p. 193. ISBN 0874519063

- ^ Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb, ISBN 0684813785.

- Bibliography

- Barry, John M. (2004). The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Greatest Plague in History. Viking Penguin. ISBN 0-670-89473-7.

- Collier, Richard (1974). The Plague of the Spanish Lady - The Influenza Pandemic of 1918–19. USA: Atheneum. ISBN 978-0689105920.

- Crosby, Alfred W. (1976). Epidemic and Peace, 1918. Westport, Ct: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-8371-8376-6.

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2003). America's Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918 (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0689105924.

- Duncan, Kirsty (2003). Hunting the 1918 flu: one scientist's search for a killer virus (illustrated ed.). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802087485.

- Ewald, Paul. Evolution of infectious disease, New York, Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Hakim, Joy (1995). War, Peace, and all that Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Honigsbaum, Mark. Living with Enza: The Forgotten Story of Britain and the Great Flu Pandemic of 1918, ISBN 978-0230217744.

- Knobler S, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon S (ed.). "1: The Story of Influenza". The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005). Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Pankhurst, Richard. An Introduction to the Medical History of Ethiopia. Trenton: Red Sea Press, 1990

- Tindall, George Brown & Shi, David Emory. America: A Narrative History, 7th ed. copyright 2007 by W.W Norton & Company, Inc.

Further reading

- Barry, John M., The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History, Viking Press, 2004. ISBN 0670894737, ISBN 978-0670894734.

- Beiner, Guy (2006). "Out in the Cold and Back: New-Found Interest in the Great Flu". Cultural and Social History. 3 (4): 496–505.

- Johnson, Niall (2006). Britain and the 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic: A Dark Epilogue. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-36560-0.

- Johnson, Niall (2003). "Measuring a pandemic: Mortality, demography and geography". Popolazione e Storia: 31–52.

- Johnson, Niall (2003). "Scottish 'flu – The Scottish mortality experience of the "Spanish flu". Scottish Historical Review. 83 (2): 216–226.

- Johnson, Niall (2002). "Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918–1920 'Spanish' influenza pandemic". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 76 (1): 105–15. doi:10.1353/bhm.2002.0022. PMID 11875246.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Kolata, Gina (1999). Flu: The Story of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and the Search for the Virus That Caused It. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-15706-5.

- Little, Jean (2007). If I Die Before I Wake: The Flu Epidemic Diary of Fiona Macgregor, Toronto, Ontario, 1918. Dear Canada. Markham, Ont.: Scholastic Canada. ISBN 9780439988377.

- Noymer, Andrew (2000). "The 1918 Influenza Epidemic's Effects on Sex Differentials in Mortality in the United States". Population and Development Review. 26 (3): 565–581. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2000.00565.x. PMC 2740912. PMID 19530360.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Oxford JS, Sefton A, Jackson R, Innes W, Daniels RS, Johnson NP (2002). "World War I may have allowed the emergence of "Spanish" influenza". The Lancet infectious diseases. 2 (2): 111–4. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00185-8. PMID 11901642.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Oxford JS, Sefton A, Jackson R, Johnson NP, Daniels RS (1999). "Who's that lady?". Nat. Med. 5 (12): 1351–2. doi:10.1038/70913. PMID 10581070.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pettit, Dorothy (2008). A Cruel Wind: Pandemic Flu in America, 1918-1920. Murfreesboro, TN: Timberlane Books. ISBN 9780971542822(Pap.).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Phillips, Howard (2003). The Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918: New Perspectives. London and New York: Routledge.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Rice, Geoffrey W. (1993). "Pandemic Influenza in Japan, 1918–1919: Mortality Patterns and Official Responses". Journal of Japanese Studies. 19 (2): 389–420. doi:10.2307/132645.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Rice, Geoffrey W. (2005). Black November: the 1918 Influenza Pandemic in New Zealand. Canterbury University Press: Canterbury Univ. Press. ISBN 1-877257-35-4.

- Tumpey TM, García-Sastre A, Mikulasova A; et al. (2002). "Existing antivirals are effective against influenza viruses with genes from the 1918 pandemic virus". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (21): 13849–54. doi:10.1073/pnas.212519699. PMC 129786. PMID 12368467.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Nature "Web Focus" on 1918 flu, including new research

- Influenza Pandemic on stanford.edu

- The Great Pandemic: The U.S. in 1918-1919. US Dept. of HHS

- Little evidence for New York City quarantine in 1918 pandemic. Nov 27, 2007 (CIDRAP News)

- Flu by Eileen A. Lynch. The devastating effect of the Spanish flu in the city of Philadelphia, PA, USA

- Dialog: An Interview with Dr. Jeffery Taubenberger on Reconstructing the Spanish Flu

- The Deadly Virus - The Influenza Epidemic of 1918 US National Archives and Records Administration - pictures and records of the time

- The 1918 Influenza Pandemic in New Zealand - includes recorded recollections of people who lived through it

- PBS - recovery of flu samples from Alaskan flu victims

- An Avian Connection as a Catalyst to the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic

- Fluwiki.com Annotated links to articles, books and scientific research on the 1918 influenza pandemic

- Alaska Science Forum - Permafrost Preserves Clues to Deadly 1918 Flu

- Pathology of Influenza in France, 1920 Report

- Yesterday's News blog 1918 newspaper account on impact of flu on Minneapolis

- "Study uncovers a lethal secret of 1918 influenza virus" University of Wisconsin - Madison, January 17, 2007

- Spanish Influenza in North America, 1918–1919

- 1918 Influenza Virus and memory B-cells - Exposure to virus generates life-long immune response.

- Influenza Research Database – Database of influenza genomic sequences and related information.

- Spanish Flu with rare pictures from Otis Historical Archives

- "No Ordinary Flu" a comic book of the 1918 flu pandemic published by Seattle & King County Public Health

- "Influenza 1918" The American Experience (PBS)

- "Closing in on a Killer: Scientists Unlock Clues to the Spanish Influenza Virus" An online exhibit from the National Museum of Health and Medicine

- Sources for the study of the 1918 influenza pandemic in Sheffield, UK Produced by Sheffield City Council's Libraries and Archives