Philip Pullman

Philip Pullman | |

|---|---|

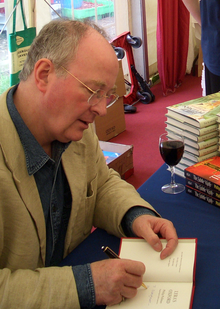

Pullman in April 2005 | |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Notable works | His Dark Materials trilogy |

| Website | |

| http://www.philip-pullman.com | |

Philip Pullman CBE (born 19 October 1946) is an English writer. He is the best-selling author of His Dark Materials (a trilogy of fantasy novels), and a number of other books. In 2008, The Times named Pullman in their list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945".[1]

Biography

Philip Pullman was born in Norwich, England to Royal Air Force pilot Alfred Outram Pullman and Audrey Evelyn Outram née Merrifield. The family travelled with his father's job, including to Southern Rhodesia where he spent time at school. His father was killed in a plane crash in 1953 when Pullman was seven. His mother remarried and, with a move to Australia, came Pullman's discovery of comic books including Superman and Batman, a medium which he continues to espouse. From 1957 he was educated at Ysgol Ardudwy school in Harlech, Gwynedd and spent time in Norfolk with his grandfather, a clergyman. Around this time Pullman discovered John Milton's Paradise Lost, which would become a major influence for His Dark Materials.

From 1963 Pullman attended Exeter College, Oxford, receiving a Third class BA in 1968[2]. In an interview with the Oxford Student he stated that he "did not really enjoy the English course" and that "I thought I was doing quite well until I came out with my third class degree and then I realised that I wasn’t — it was the year they stopped giving fourth class degrees otherwise I’d have got one of those".[3] He discovered William Blake's illustrations around 1970, which would also later influence him greatly.

Pullman married Judith Speller in 1970 and began teaching children and writing school plays. His first published work was The Haunted Storm, which joint-won the New English Library's Young Writer's Award in 1972. He nevertheless refuses to discuss it. Galatea, an adult fantasy-fiction novel, followed in 1978, but it was his school plays which inspired his first children's book, Count Karlstein, in 1982. He stopped teaching around the publication of The Ruby in the Smoke (1986), his second children's book, whose Victorian setting is indicative of Pullman's interest in that era.

Pullman taught part-time at Westminster College, Oxford between 1988 and 1996, continuing to write children's stories. He began His Dark Materials about 1993. Northern Lights (published as The Golden Compass in the US) was published in 1995 and won the Carnegie Medal, one of the most prestigious British children's fiction awards, and the Guardian Children's Fiction Award.

Pullman has been writing full-time since 1996, but continues to deliver talks and writes occasionally for The Guardian. He was awarded a CBE in the New Year's Honours list in 2004. He also co-judged the prestigious Christopher Tower Poetry Prize (awarded by Oxford University) in 2005 with Gillian Clarke. Pullman also began lecturing at a seminar in English at his alma mater, Exeter College, Oxford, in 2004.[4][5]

In 2005 he was awarded The Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award by the Swedish Arts Council.

He is currently working on The Book of Dust, a sequel to his completed His Dark Materials trilogy and "The Adventures of John Blake", a story for the British children's comic The DFC, with artist John Aggs.[6][7][8]

On 23 November 2007, Pullman was made an honorary professor at Bangor University.[9] In June 2008, Pullman became a Fellow supporting the MA in Creative Writing at Oxford Brookes University.[10] In September 2008 Pullman hosted "The Writer's Table" for Waterstone's bookshop chain, highlighting 40 books which have influenced his career.[11] In October 2009 he became a patron of the Palestine Festival of Literature.

Pullman has a strong commitment to traditional British civil liberties and is noted for his criticism of growing state authority and government encroachment into everyday life. In February 2009, he was the keynote speaker at the Convention on Modern Liberty in London[12] and wrote an extended piece in The Times condemning the Labour government for its attacks on basic civil rights.[13] Later, he and other authors threatened to stop visiting schools in protest at new laws requiring them to be vetted to work with youngsters — though officials claimed that the laws had been misinterpreted.[14]

On 24 June 2009, Pullman was awarded the degree of D. Litt. (Doctor of Letters), honoris causa, by the University of Oxford at the Encænia ceremony in the Sheldonian Theatre.[15]

His Dark Materials

His Dark Materials is a trilogy consisting of Northern Lights (titled The Golden Compass in North America), The Subtle Knife and The Amber Spyglass. The first volume, "Northern Lights", won the Carnegie Medal for children's fiction in the UK in 1995. The Amber Spyglass, the last volume, was awarded both 2001 Whitbread Prize for best children's book and the Whitbread Book of the Year prize in January 2002, the first children's book to receive that award. The series won popular acclaim in late 2003, taking third place in the BBC's Big Read poll. Pullman has written two companion pieces to the trilogy, entitled Lyra's Oxford, and the newly released Once Upon a Time in the North. A third companion piece Pullman refers to as the "green book" will expand upon his character Will. He has plans for one more, the as-yet-unwritten The Book of Dust. This book is not a continuation of the trilogy but will include characters and events from His Dark Materials.

In 2005 Pullman was announced as joint winner of the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award for children's literature.

Perspective on religion

Pullman is a supporter of the British Humanist Association and an Honorary Associate of the National Secular Society. New Yorker journalist Laura Miller has described Pullman as one of England's most outspoken atheists.[16]

The His Dark Materials books have been criticised by the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights[17] and Focus on the Family[18]. Peter Hitchens has argued that Pullman actively pursues an anti-Christian agenda.[19] In support of this contention, he cites an interview in which Pullman is quoted as saying: "I'm trying to undermine the basis of Christian belief."[20] In the same interview, Pullman also acknowledges that a controversy would be likely to boost sales. "But I'm not in the business of offending people. I find the books upholding certain values that I think are important, such as life is immensely valuable and this world is an extraordinarily beautiful place. We should do what we can to increase the amount of wisdom in the world".[20]

Peter Hitchens views the His Dark Materials series as a direct rebuttal of C. S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia[21] and Pullman has criticized the Narnia books as religious propaganda.[22] Both Pullman's and Lewis's books contain religious allegory that features talking animals, parallel worlds, and children who face adult moral choices that determine the ultimate fate of those worlds.

Christopher Hitchens, author of God Is Not Great, praised His Dark Materials as a fresh alternative to C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien and J. K. Rowling. He described the author as one "whose books have begun to dissolve the frontier between adult and juvenile fiction."[23]

Literary critic Alan Jacobs (of Wheaton College) said that in His Dark Materials Pullman replaced the theist world-view of John Milton's Paradise Lost with a Rousseauist one.[24] Donna Freitas, professor of religion at Boston University, argued on BeliefNet.com that challenges to traditional images of God should be welcomed as part of a "lively dialogue about faith", and Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, has proposed that His Dark Materials be taught as part of religious education in schools.[25] The Christian writers Kurt Bruner and Jim Ware "also uncover spiritual themes within the books."[26]

Screen adaptations

- A mini-series adaptation of I Was a Rat was produced by the BBC and aired in three one-hour installments in 2001.

- A film adaptation of The Butterfly Tattoo[27] finished principal photography on 30 September 2007. The Butterfly Tattoo is a project, supported by Philip Pullman, to allow young artists a chance to gain experience in the film industry. The film is produced by the Dutch production company Dynamic Entertainment.

- A co-produced BBC and WGBH Boston television adaptation of The Ruby in the Smoke, starring Billie Piper and Julie Walters, was screened in the UK on BBC One on 27 December 2006, and broadcast on PBS Masterpiece Theatre in America on 4 February 2007. The television adaptation of the second book in the series, The Shadow in the North, aired on the BBC on 26 December 2007. The BBC and WGBH announced plans to adapt the next two Sally Lockhart novels, The Tiger in the Well, and The Tin Princess, for television as well; however, since The Shadow in the North aired in 2007, no information has arisen regarding an adaptation of The Tiger in the Well..

- A film adaptation of Northern Lights, titled The Golden Compass, was released in December 2007 by New Line Cinema, starring Nicole Kidman, Daniel Craig, Eva Green, Sam Elliott, Ian McKellen, and Dakota Blue Richards.

Bibliography

Pullman's books include the following works.[28]

Non-series books

- 1972 The Haunted Storm

- 1976 Galatea

- 1982 Count Karlstein

- 1987 How to be Cool

- 1989 Spring-Heeled Jack

- 1990 The Broken Bridge

- 1992 The White Mercedes

- 1993 The Wonderful Story of Aladdin and the Enchanted Lamp

- 1995 Clockwork, or, All Wound Up

- 1995 The Firework-Maker's Daughter

- 1998 Mossycoat

- 1998 The Butterfly Tattoo (re-issue of The White Mercedes)

- 1999 I was a Rat! or The Scarlet Slippers

- 2000 Puss in Boots: The Adventures of That Most Enterprising Feline

- 2004 The Scarecrow and his Servant

- 2010 The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ

Sally Lockhart

- 1985 The Ruby in the Smoke

- 1986 The Shadow in the North (first published as The Shadow in the Plate)

- 1991 The Tiger in the Well

- 1994 The Tin Princess

The New-Cut Gang

- 1994 Thunderbolt's Waxwork

- 1995 The Gasfitter's Ball

His Dark Materials

- 1995 Northern Lights, retitled The Golden Compass in the US

- 1997 The Subtle Knife

- 2000 The Amber Spyglass

Companion books

- 2003 Lyra's Oxford

- 2008 Once Upon a Time in the North

- No release date The Book of Dust (not yet published)

Plays

- 1990 Frankenstein

- 1992 Sherlock Holmes and the Limehouse Horror

Non-fiction

- 1978 Ancient Civilisations

- 1978 Using the Oxford Junior Dictionary

Comics

- 2008 The Adventures of John Blake in The DFC

References

- ^ The 50 greatest British writers since 1945. 5 January 2008. The Times. Retrieved on 2010-02-05.

- ^ "University of Oxford, Cherwell newspaper Interviews: Philip Pullman". Cherwell. 2009-09-02. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

- ^ Growing Pains - Features - The Oxford Student - Official Student Newspaper

- ^ http://www.uce.ac.uk/web2/releases04/3476.html

- ^ http://www.exeter.ox.ac.uk/admissions/undergrad/life/

- ^ Philip Pullman writes comic strip, The Times, May 11, 2008

- ^ Deep stuff, The Guardian, May 24, 2008

- ^ The DFC homepage, The DFC

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/wales/7109377.stm

- ^ "Philip Pullman Creative Writing Fellow for new MA". Oxford Brookes University. 2008-06-11. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- ^ "Philip Pullman To Host Next Waterstone's Writer's Table". booktrade.info. 2008-07-02. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- ^ http://www.modernliberty.net/2009/philip-pullmans-keynote

- ^ http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/columnists/guest_contributors/article5811412.ece

- ^ BBC news School safety 'insult' to Pullman, 16 July 2009

- ^ [1]

- ^ Miller, Laura. "'Far From Narnia'" (Life and Letters article). The New Yorker. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- ^ ""The Golden Compass" Sparks Protest". Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights.

- ^ Jennifer Mesko. "Golden Compass Reveals a World Where There is No God". Focus on the Family citizenlink.com. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ "'This is the most dangerous author in Britain'" (Mail on Sunday article). The Mail on Sunday. Retrieved 2006-09-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|autld hor=ignored (help) - ^ a b "The Last Word". The Washington Post. 2001-02-19. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- ^ Hitchens, Peter. "A labour of loathing" (Spectator article). The Spectator. Retrieved 2006-09-21.

{{cite news}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Crary, Duncan. "The Golden Compass Author Avoids Atheist Labels" (Humanist Network News Interview). Humanist Network News. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- ^ Oxford's Rebel Angel

- ^ "Mars Hill Audio - Audition - Program 10". Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- ^ "Golden Compass Film Angering Christian Groups -- Even With Its Religious Themes Watered Down". MTV Asia.

- ^ Bruner, Kurt & Ware, Jim. "'Shedding Light on His Dark Materials'" (Tyndale Products review). Tyndale. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Butterfly Tattoo - Home

- ^ "Philip Pullman". FantasticFiction.

Further reading

- Lenz, Millicent (2005). His Dark Materials Illuminated: Critical Essays on Phillip Pullman's Trilogy. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3207-2.

- Wheat, Leonard F. Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials - A Multiple Allegory: Attacking Religious Superstition in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and Paradise Lost.

- Robert Darby: Intercision-Circumcision: His Dark Materials, a disturbing allegory of genital mutilation [2]

External links

- Philip-Pullman.com Official site

- Philip Pullman at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Philip Pullman at IMDb

- Philip Pullman at House of Legend

- Philip Pullman at Random House Australia

- Interview: Philip Pullman: new brand of environmentalismThe Daily Telegraph, January 19, 2008, "Paradise regained" Extract from interview with Pullman in Do Good Lives Have to Cost the Earth?

- Article: Philip Pullman: Kill humans and ration heating The Register, January 21, 2008, ""This is a crisis as big as war"

- Article: Pullman criticizes modern fiction The Guardian, August 12, 2002, "Fiction becoming trivial and worthless, says top author".

- Dark Materials debate: life, God, the universe... Article: Philip Pullman and Rowan Williams debate on Religion in His Dark Materials

- 1946 births

- Living people

- 20th-century English people

- 21st-century English people

- English children's writers

- English fantasy writers

- English novelists

- English atheists

- British Book Awards

- Guardian award winners

- British humanists

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- Alumni of Exeter College, Oxford

- People from Norwich

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- Academics of Oxford Brookes University

- People associated with Bangor University