Hestia

| Hestia | |

|---|---|

| Equivalents | |

| Roman | Vesta |

>

In Roman mythology, her more specifically civic approximate equivalent was Vesta, who personified the public hearth, and whose cult round the ever-burning hearth bound Romans together in the form of an extended family. The similarity of names between Hestia and Vesta, is misleading: "The relationship hestia-histie-Vesta cannot be explained in terms of Indo-European linguistics; borrowings from a third language must also be involved," Walter Burkert has written[1]. At a deep level her name means "home and hearth", the oikos, the household and its inhabitants. "An early form of the temple is the hearth house; the early temples at Dreros and Prinias on Crete are of this type as indeed is the temple of Apollo at Delphi which always had its inner hestia"[2]Among classical Greeks the altar was always in the open air with no roof but the sky, and that of the oracle at Delphi was the shrine of the Goddess before it was assumed by Apollo. The Mycenaean great hall, such as the hall of Odysseus at Ithaca was a megaron, with a central hearthfire.

The hearth fire of a Greek or a Roman household was not allowed to go out, unless it was ritually extinguished and ritually renewed, accompanied by impressive rituals of completion, purification and renewal. Compare the rituals and connotations of an eternal flame and of sanctuary lamps. At the more developed level of the polis, Hestia symbolizes the alliance between the colonies and their mother cities.

As an Olympian

Hestia is one of the three great goddesses of the first Olympian generation: Hestia, Demeter and Hera. She was described as both the oldest and youngest[3] of the three daughters of Rhea and Kronos, the sisters to three brothers Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades. Originally listed as one of the Twelve Olympians, Hestia gave up her seat in favour of newcomer Dionysus to tend to the sacred fire on Mt. Olympus. However, there is no ancient source for this claim. As Karl Kerenyi observes,[4]"there is no story of Hestia's ever having taken a husband or ever having been removed from her fixed abode." Every family hearth was her altar.

Of the Olympian gods, Hestia has the fewest exploits "since the hearth is immovable, Hestia is unable to take part even in the procession of the gods, let alone the other antics of the Olympians," Burkert remarks.[5]Sometimes this is assumed to be due to her passive, non-confrontational nature. This nature is illustrated by her giving up her seat in the Olympian twelve to prevent conflict. She is considered to be the first-born of Rhea and Kronos; this is evidenced by the fact that in Greek (and later Roman) culture ritual offerings to all gods began with a small offering to Hestia; the phrase "Hestia comes first" from ancient Greek culture denotes this.[6]

Immediately after their birth, Kronos swallowed Hestia and her siblings except for the last and youngest, Zeus, who later rescued them and led them in a war against Kronos and the other Titans. Hestia, the eldest daughter "became their youngest child, since she was the first to be devoured by their father and the last to be yielded up again" (Kereny 1951:91) — the clearest possible example of mythic inversion, a paradox that is noted in the Homeric hymn to Aphrodite (ca 700 BCE):

She was the first-born child of wily Kronus — and youngest too.

Poseidon, and Apollo of the younger generation each aspired to court Hestia, but the goddess was unmoved by Aphrodite's works and swore on the head of Zeus to retain her virginity. The Homeric hymns, like all early Greek literature, are concerned to reinforce the supremacy of Zeus, and Hestia's oath taken upon the head of Zeus is an example of surety. A measure of the goddess's ancient primacy—"queenly maid...among all mortal men she is chief of the goddesses", in the words of the Homeric hymn— is that she was owed the first as well as the last sacrifice at every ceremonial assembly of Hellenes, a pious duty related by the mythographers as the gift of Zeus, as if it had been his to bestow: another mythic inversion if, as is likely, the ritual was too deep-seated and essential for the Olympian reordering to overturn. There are theories (by modern neopagans among others) that Hestia, as goddess of "home and hearth", was one of the most ancient of all gods later worshipped as Olympians; as a maternal goddess of humans finding safety and homes in caves around a fire, worship of Hestia, by other names, may literally be hundreds of thousands of years old and has continued through classical Greek times to the present day.

"The power worshipped in the hearth never fully developed into a person," Walter Burkert has observed.[7]Hestia evolved into a lesser goddess in the same ranks of Pan and Dionysus, who was incorporated into the Olympian order in Hestia's place. At Athens "in Plato's time," notes Kenneth Dorter[8]"there was a discrepancy in the list of the twelve chief gods, as to whether Hestia or Dionysus was included with the other eleven. The altar to them at the agora, for example, included Hestia, but the east frieze of the Parthenon had Dionysus instead.

Other worship

The "great hall" of Minoan-Mycenaean culture as well as the type of earliest enclosed site built for worship on the Greek mainland is the megaron: the name of the Goddess who was venerated in the Helladic megara is not recorded, but at the center of each holy site laid bare by archaeologists was normally a hearth.

In his account of the Fasti of the Roman year, Ovid twice recounted an anecdote of Priapus's foiled attempt on a sleeping nymph: once he told it of the nymph Lotis[9]and then again, calling it a "very playful little tale", he retold it of Vesta, the Roman equivalent of Hestia.[10]In the anecdote, after a great feast, when the immortals were all either passed out drunk or asleep, Priapus — who had grotesquely large genitalia — spied Lotis/Vesta and was filled with lust for her. He quietly approached the nymph, but the braying of an ass awoke her just in time. She screamed at the sight and Priapus ran away.

In mythology

Hestia figures in few myths: she did not roam nor did she have any adventures. The Homeric hymn To Hestia is consequently brief, simply an invocation of five lines, a prelude:

Hestia, you who tend the holy house of the lord Apollo, the Far-shooter at goodly Pytho, with soft oil dripping ever from your locks, come now into this house, come, having one mind with Zeus the all-wise: draw near, and withal bestow grace upon my song.

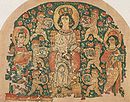

In the hymn, Hestia is located in ancient Delphi (rather than at the hearth of Zeus on Mount Olympus), which was considered the central hearth of all the Hellenes. In classical Greek art, Hestia was depicted as a woman modestly cloaked in a head veil.

References

- ^ Burkert, Greek Religion 1985:III.3.1 note 2.

- ^ Burkert p 61.

- ^ See below.

- ^ Kerenyi, The Gods of the Greeks, 1951:92.

- ^ Burkert, Greek Religion 1985:170.

- ^ Not so for every Greek in every generation, however: in Odyssey 14, 432-36, the loyal swineherd Eumaeus, when entertaining in his hut the still-unrecognized Odysseus, began the feast by plucking tufts from the boar's head and throwing them into the fire with a prayer addressed to all the powers, then carved the meat into seven equal portions: "one he set aside, lifting up a prayer to the forest nymphs and Hermes, Maia's son." (Robert Fagles' translation).

- ^ Burkert 1985: III.3.1, p. 170.

- ^ Dorter, "Imagery and Philosophy in Plato's Phaedrus," Journal of the History of Philosophy 9.3 (July 1971:279-88).

- ^ Ovid, Fasti, 1.391ff (on-line text).

- ^ Fasti 6.319ff (on-line text).

Sources

- Burkert, Walter, 1985. Greek Religion (Harvard University Press)

- Kerenyi, Karl, 1951. The Gods of the Greeks

- Stephenson, Hamish, 1985. "The Gods of the Romans and Greeks" (NYT Writer)

External links

- Carlos Parada, "Hestia"

- Homeric hymns To Aphrodite and To Hestia

- Ovid, Fasti (Vesta)

- Socrates to Hermogenes about Hestia - Estia - Esti (Eesti) - Osia

- Theoi Project: Hestia Excerpts in translation of Classical texts.]